JUMP TO: FRUSTRATION – National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina | Salam Air SAOC v LATAM Airlines Group | Wilmington Trust SP Services v SpiceJet | The ‘Sea Angel’ | Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines v Steamship Mutual Underwriting Association – IMPOSSIBILITY – Taylor v Caldwell | Appleby v Myers | Condor v The Barron Knights | Morgan v Manser | Jackson v Union Marine Insurance | Nicholl and Knight v Ashton, Edridge and Co – SUPERVENING ILLEGALITY – Denny, Mott & Dickinson v James B. Fraser & Co | Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour – FRUSTRATION OF COMMON PURPOSE – Krell v Henry | Herne Bay Steamboat v Hutton | Canary Wharf v European Medicines Agency – LIMITS TO FRUSTRATION – Davis Contractors v Fareham Urban District Council | Tsakiroglou & Co. v Noblee Thorl | Maritime National Fish v Ocean Trawlers | The ‘Super Servant Two’ | Amalgamated Investment & Property Co. v John Walker & Sons | Walton Harvey Ltd v Walker and Homfrays

FRUSTRATION

Frustration happens if an intervening event, which was no fault of either party, radically changes the nature of the contractual obligations so that neither party can reasonably be held to performance of the contract. The contract is void from the time of the frustrating event. Although this might sound like a mistake, it is different due to the timing of the event that radically changes the situation. A mistake occurs when parties were mistaken at the time of contract formation thus the contract is void ab initio (from the beginning). A frustrating event occurs after the contract has been concluded.

‘Frustration of a contract takes place when there supervenes an event (without default of either party and for which the contract makes no sufficient provision) which so significantly changes the nature (not merely the expense or onerousness) of the outstanding contractual rights and/or obligations from what the parties could reasonably have contemplated at the time of its execution that it would be unjust to hold them to the literal sense of its stipulations in the new circumstances; in such case the law declares both parties to be discharged from further performance.’ Lord Simon, National Carriers Ltd v Panalpina Ltd (1981) (HoL)

A frustrating event can only occur when no party has been assigned the risk for that event. A force majeure clause in the contract that assigns risk between the parties for certain events avoids frustration.

While the doctrine of frustration remains a key part of English law, it is worth noting that the doctrine is very difficult to invoke. There are very few modern cases that have successfully argued that a frustrating event has occurred. This is because it is very difficult to argue that something is unforeseeable and could not have been reasonably contemplated by the parties. Even the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit (the UK’s departure from the EU) were not found to be a frustrating events, and parties are expected to safeguard against eventualities through drafting adequate contractual clauses.

For cases arguing that Covid-19 was a frustrating event, see Salam Air SAOC v LATAM Airlines Group (2020) (HC) and Wilmington Trust SP Services (Dublin) Ltd v SpiceJet Ltd (2021) (HC). Brexit was considered in Canary Wharf (BP4) T1 Ltd v European Medicines Agency (2019) (HC).

THE COURTS’ APPROACH TO FRUSTRATION

When deciding whether or not a contract has been frustrated, the courts have adopted a ‘multifactorial’ approach (Edwinton Commercial Corp, Global Tradeways Limited v Tsavliris Russ (Worldwide Salvage & Towage) Ltd (The ‘Sea Angel’) (2007) (CoA)).

|

These factors include:

- the terms of the contract itself,

- its matrix or context,

- the parties’ knowledge, expectations, assumptions and contemplations, in particular as to risk, as at the time of contract, at any rate so far as these can be ascribed mutually and objectively, and then

- the nature of the supervening event,

- the parties’ reasonable and objectively ascertainable calculations as to the possibilities of future performance in the new circumstances.

|

Factors [1] – [3] are ‘ex ante factors’, meaning before the event. Factors [4] – [5] are post-contractual. (Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines v Steamship Mutual Underwriting Association (Bermuda) Ltd (2010) (HC)).

The courts have determined that frustrating events include: impossibility of performing the contract, supervening illegality and frustration of the commercial purpose of the contract.

IMPOSSIBILITY

A contract will be frustrated if it becomes impossible to perform through destruction, death or illness, or unavailability.

DESTRUCTION

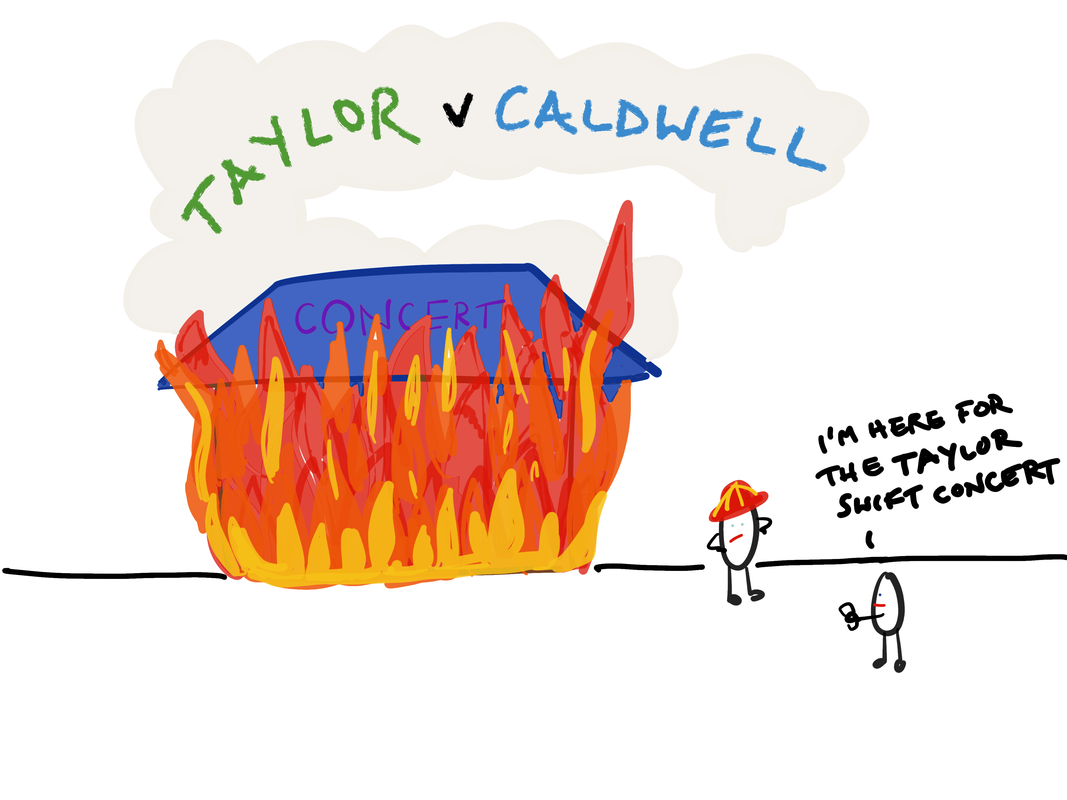

The partial or total destruction of something that is essential to performance will frustrate the contract (Taylor v Caldwell (1863) (HC)).

Taylor had hired a hall from Caldwell in which to hold a series of concerts. Before the concerts were performed the hall burnt down. Taylor sued Caldwell for breach of contract. As the fire had not been caused by the fault of either party the court decided that the contract had been frustrated by the destruction of the music hall.

This is also true if something is destroyed that is not the subject of the contract but is essential for performance. In Appleby v Myers (1867) (Court of Exchequer) the destruction of a factory frustrated a contract for maintenance of the factory equipment.

DEATH OR ILLNESS

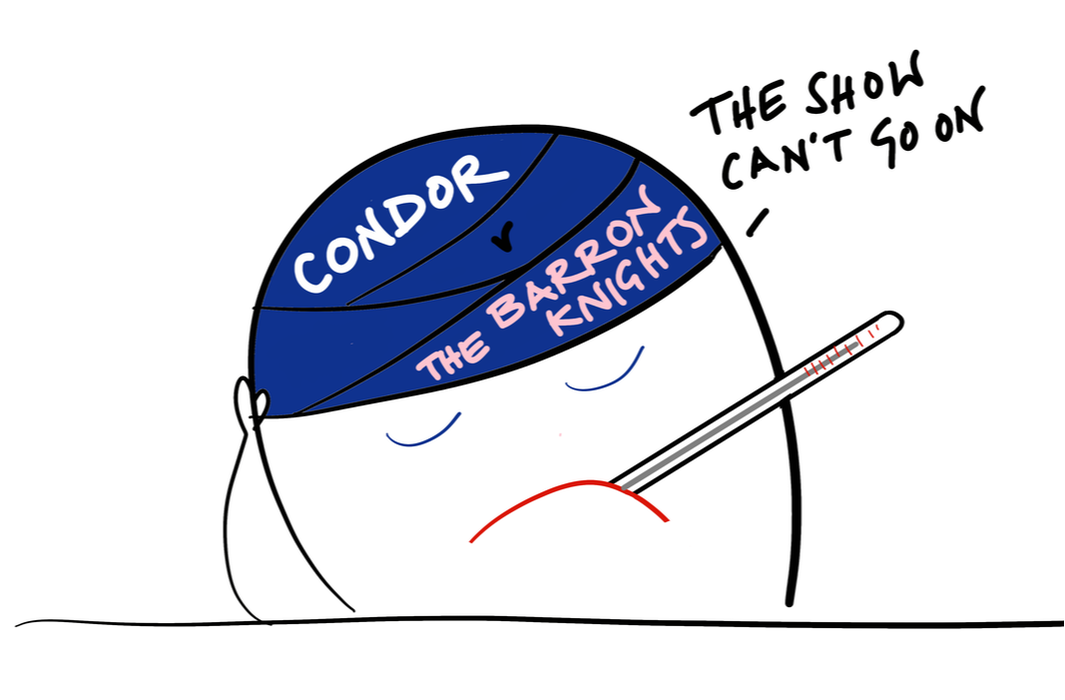

If a party to a personal contract (i.e. one that only that party could perform) dies then the contract will be frustrated. If the party is unavailable for the length of the contract through no fault of their own then this will also frustrate the contract (Condor v The Barron Knights (1966) (Assizes)).

A young musician was contracted to play with the Barron Knights 7 days a week for 5 years. He suffered a mental breakdown and his doctor said he should only work 4 nights a week. On this basis the band dismissed him. He sued them for wrongful dismissal but was unsuccessful because the court held that his illness was a frustrating event which released the parties from future obligations. It was not the fault of either party and if he was unable to play with the band whenever they had a concert that was a radical change to the nature of their contractual obligations.

In Morgan v Manser (1948) a music hall artist’s contract was frustrated because he was called up for military service.

UNAVAILABILITY

Unavailability of the subject matter, even temporarily, may frustrate the contract. Whether a contract has been frustrated by temporary unavailability will depend on the length of the delay and the effect this has on the overall performance of the contract (Jackson v Union Marine Insurance (1874) (Court of Exchequer)).

A ship was chartered to sail from Liverpool to San Francisco via Newport. It ran aground outside Liverpool and could not complete the journey until eight months later. The court held that there was an implied term in the contract that performance would be completed in reasonable time. Such a long delay frustrated the contract. A voyage to San Francisco which was eight months late was performance radically different from that originally contemplated.

The unavailability of a specific method of performance can frustrate the contract. In Nicholl and Knight v Ashton, Edridge and Co (1901) (CoA) the specific ship named in the contract was unavailable due to repairs and the contract was frustrated.

SUPERVENING ILLEGALITY

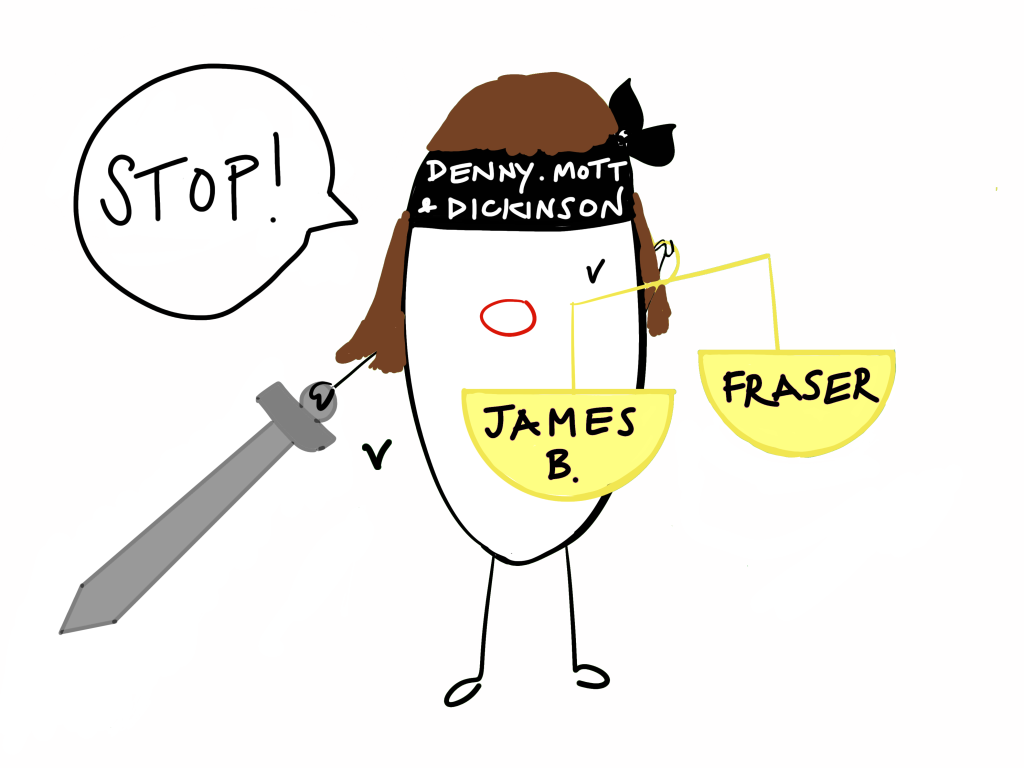

A contract will be frustrated if performance has become illegal since the formation of the contract (Denny, Mott & Dickinson v James B. Fraser & Co. (1944) (HoL)).

A contract for the sale of timber was frustrated by the Control of Timber (No 4) Order 1939 which made the performance of the contract illegal.

In Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd (1943) (HoL) an English company agreed to manufacture machines for a Polish company and to deliver them to Gdynia in Poland. However, before the English company could complete manufacturing the machines, Gdynia was occupied by the German army. It was held that the contract was frustrated because in time of war it is against the law to trade with the enemy. It was public policy to not provide assistance to the enemy during war.

Temporary illegality may frustrate a contract but it will depend upon the length and effect of the change in the law. In National Carriers v Panalpina (1981) (HoL) the local council blocked access to a warehouse, leased by the defendants from the claimants, for 20 months of a ten year contract. This was not long enough to equal frustration of the contract.

FRUSTRATION OF COMMON PURPOSE

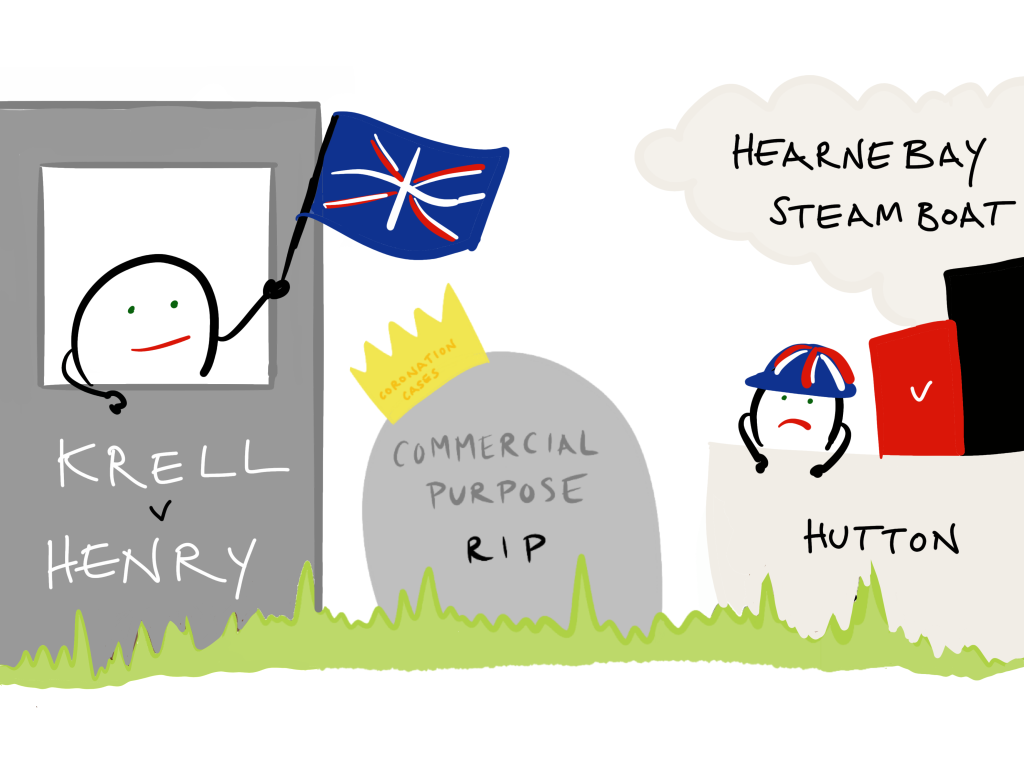

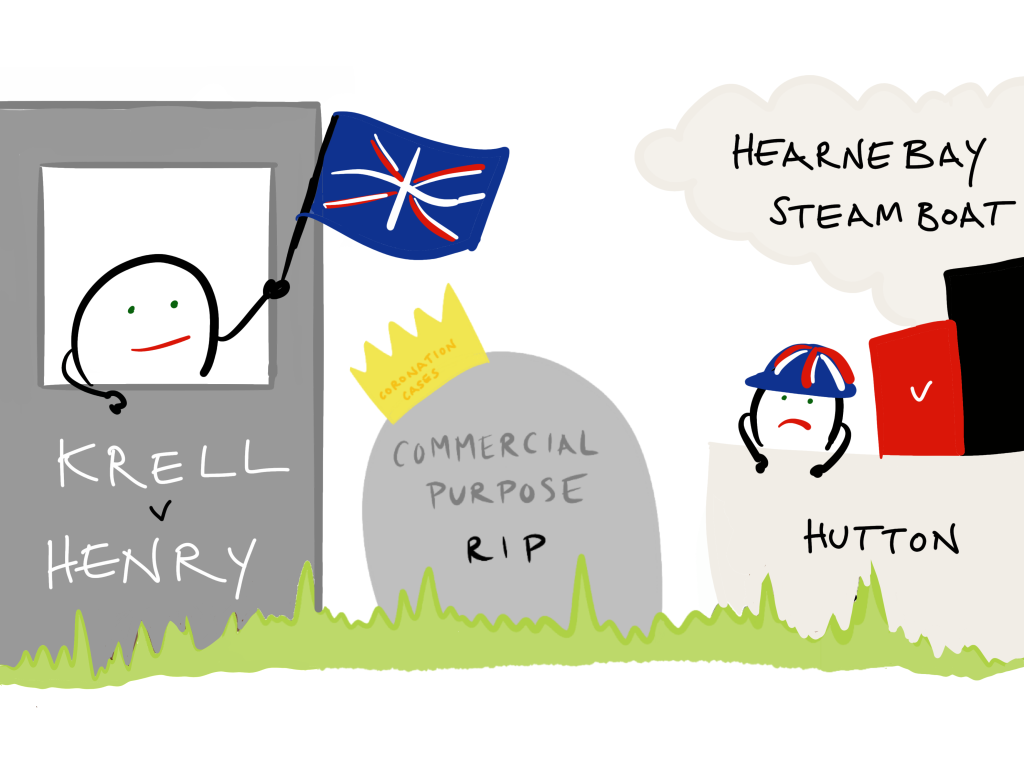

If the common commercial purpose for which the contract was entered into can no longer be performed then the contract will be frustrated. This is only true if the joint purpose, i.e. the purpose of both and not only one party, is destroyed. If some part of the contract is still possible then it will not have been frustrated. This is demonstrated by two cases known together as the ‘Coronation Cases’.

| In Krell v Henry (1903) (CoA) Henry had contracted with Krell to hire a flat along the route of the King’s coronation procession from which to view the celebrations. When the coronation was postponed Henry refused to pay. The court found that the sole purpose of the contract had been destroyed and the contract frustrated. Therefore Henry did not have to pay for the hire. |

In Herne Bay Steamboat v Hutton (1903) (CoA) Hutton had hired a private steamboat in order to see the coronation naval review and cruise around the naval fleet. When the coronation naval review was cancelled Hutton refused to pay. However, in this case the court found no frustration because Hutton could still have used the boat for the purpose of viewing the fleet. The whole purpose of the contract had not been destroyed by the absence of the King. |

In Canary Wharf (BP4) T1 Ltd v European Medicines Agency (2019) (HC) the European Medicines Agency was the tenant of a property at Canary Wharf under a 25 year lease running until 2039 (with no break clauses) at a current passing rent of £13m a year. After Brexit the European Medicines Agency was no longer able to operate its headquarters within the UK because EU law prohibited it from doing so. The European Medicines Agency argued that the tenancy agreement had been frustrated as they wanted to escape the lease. The court found that the contract had not been frustrated because there was nothing stopping the Medicines Agency from leasing property outside of the EU even if the headquarters had to move back to Europe. The common purpose was therefore not frustrated as there was no mutual understanding that the purpose of the lease was to provide a headquarters for the European Medicines Agency.

LIMITS TO FRUSTRATION

The courts have developed limitations to the use of frustration.

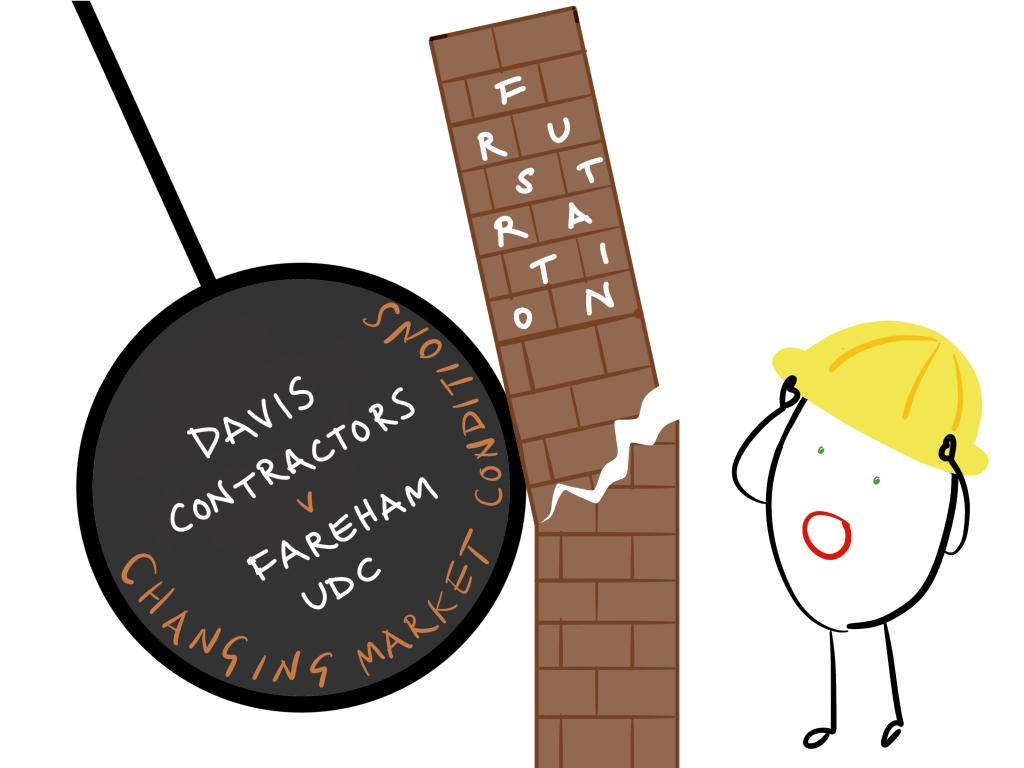

CHANGING MARKET CONDITIONS

Frustration cannot be used simply because the contract has become more difficult or expensive to perform (Davis Contractors v Fareham Urban District Council (1956) (HoL)).

Davis was contracted to build houses for Fareham Council for a fixed price. A shortage of skilled labour led to a delay of 14 months. Davis tried to argue that this event had frustrated the contract and that they should be paid for the partial amount that they had built (quantum meruit). The court disagreed, just because the contract had become more expensive did not mean that it had been frustrated.

Another example is Tsakiroglou & Co. v Noblee Thorl (1962) (HoL) in which a ship delivering peanuts from Sudan to Hamburg could not take the shorter route through the Suez Canal due to the Suez Crisis. The defendants tried to argue that the contract had been frustrated by this event. However, the availability of an alternative route around the Cape of Good Hope (and that fact that the contract did not specify which route should be taken) meant that it was still possible to perform even though the journey would be longer and more expensive. Therefore it had not been frustrated.

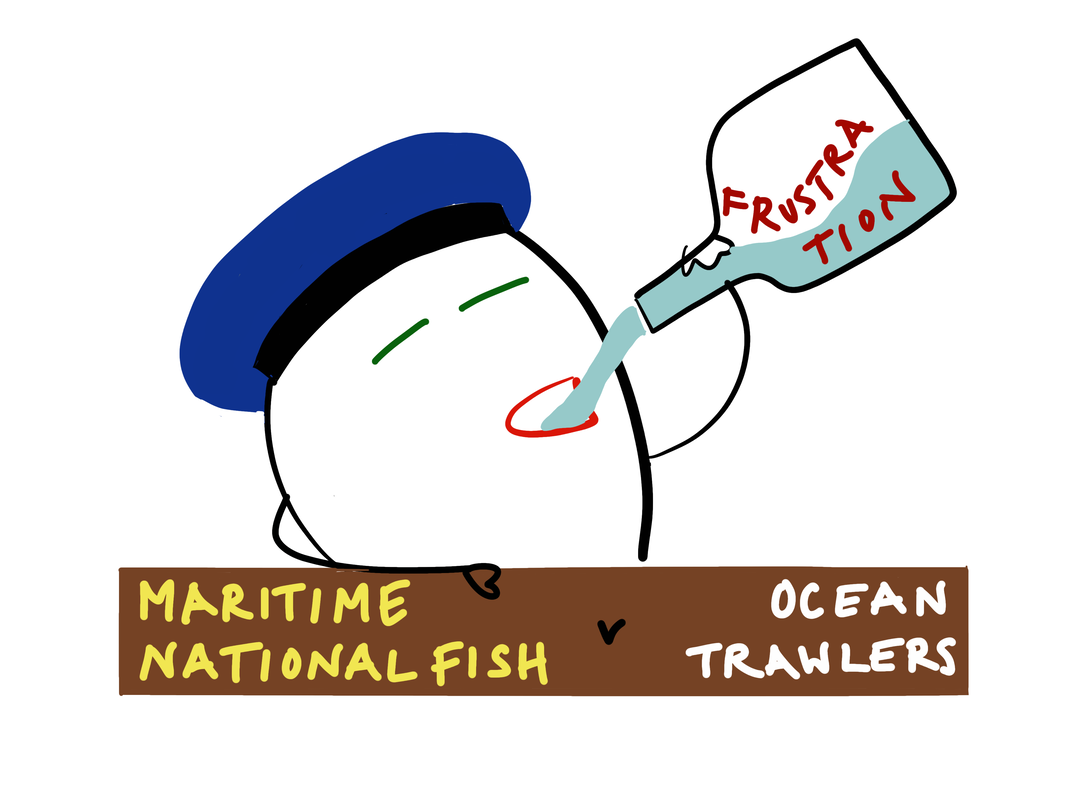

SELF-INDUCED FRUSTRATION

Frustration cannot be used if the intervening event was caused by one of the parties (Maritime National Fish v Ocean Trawlers (1935) (PC)).

Ocean Trawlers hired a boat, the St Cuthbert, from Maritime National Fish. For it to be usable as a fishing vessel Ocean Trawlers had to apply for a licence. They did this but were only allowed three licences for five ships and chose not to licence the St Cuthbert. They then tried to claim that this had frustrated the contract; the court disagreed because their lack of permit was self-induced.

In J Lauritzen AS v Wijsmuller BV (The ‘Super Servant Two’) (1990) (CoA) the defendants agreed to transport the claimant’s oil rig using one of two ships: either Super Servant One or Super Servant Two. Both were self propelling barges designed specifically for transporting oil rigs. Prior to performing the contract the defendants decided that they would use Super Servant Two for the claimant’s oil rig and they used Super Servant One for another job. Unfortunately, Super Servant Two sank before the defendant could transport the claimant’s rig and Super Servant One was no longer available. The claimants sued the defendants for breach of contract and the defendants argued that the contract was frustrated because there was no ship available. The Court of Appeal held that the cause of the non-performance of the contract was not the sinking of Super Servant Two but the choice of the defendants to allocate Super Servant One to the performance of other contracts. It was therefore the defendant’s own fault that they could no longer perform the contract, it had not been frustrated.

Frustration cannot be used if the event occurred due to the negligence of the defendant. This was discussed in Taylor v Caldwell (1863) (HC), if the hall had burnt down because of the negligence of the owner they would not have been able to use frustration as a defence.

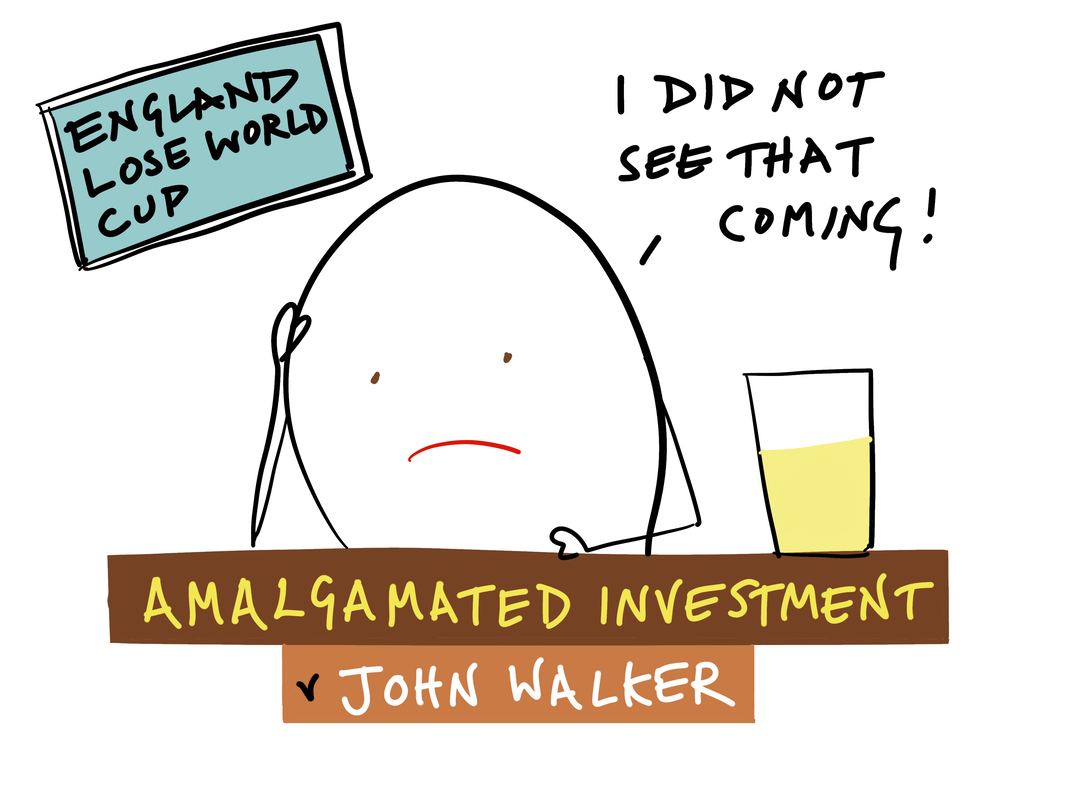

FORESEEABLE EVENTS

If an event was foreseeable it cannot be frustrating, ‘the less that an event, in its type and impact, is foreseeable, the more likely it is to be a factor which…may lead on to frustration’, (Amalgamated Investment & Property Co. v John Walker & Sons (1976) (CoA)).

A property was sold for its redevelopment potential. Two days after completion of the contract the property was officially listed as one of architectural or historical interest after which it had no redevelopment value. The court refused to find this event frustrating stating that the fact that the building might be listed should have been foreseeable given that the developers had enquired about the possibility before purchase.

In Walton Harvey Ltd v Walker and Homfrays Ltd (1931) (CoA) the defendant granted to the claimant the right to display an advertising sign for seven years on the defendant’s hotel. Before the seven years had elapsed the local authority compulsorily purchased the hotel and demolished it. The court found that the compulsory purchase and demolition was not a frustrating event because it was within the contemplation of the defendant at the time that the contract was concluded that the property might be the subject of a compulsory purchase order.

In general, events that are provided for in the contract cannot lead to frustration as they were foreseen and one party will have taken on the risk of that event happening. However, even expressly provided for events may lead to frustration, for example, a strike that goes on much longer than could have been foreseen.

EFFECT OF FRUSTRATION

A frustrating event automatically terminates any future contractual obligations. What happens to contractual duties that have already been performed is governed by the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943. Prior to this Act, frustrated contracts would result in each party having to suffer their own losses. The common law position is that ‘the loss lay where it fell’ (Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd (1943) (HoL)). However, this could lead to unfairness. Therefore the Act was implemented to allow each party to recover costs incurred or to seek payment for performance up until the frustrating event.

If, for example, one party has already paid for something, e.g. hire of a room, and the contract is then frustrated the courts can reward them repayment. This can be full repayment or a sum that seems just in the circumstances, but never more than the amount paid.