ACCEPTANCE OF AN OFFER

‘Acceptance is a final and unqualified expression of assent to the terms of an offer’.

Edwin Peel, Treitel on the The Law of Contract (15th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2020)

THE MIRROR IMAGE

To form a valid contract the offer must be accepted. Acceptance forms a clear indication of the offeree’s commitment to the terms of the offer. Acceptance must be an unqualified, ‘mirror-image’ of the offer. Any attempt to change the terms will be an implied rejection (Hyde v Wrench (1840) (HC)).

Wrench offered to sell Hyde a farm for £1,000. Hyde offered to pay £950 instead. This was not a ‘mirror image’ of the offer and therefore not a valid acceptance. It was a counter offer and a rejection of the original offer.

There is no formal need for the offeree to use the word ‘accept’ or ‘acceptance’, nor is it required that the offeree express an acceptance of every term of the offer. If the court is satisfied of acceptance, that acceptance will extend to all the terms of the offer (Arcadis Consulting v AMEC (2018) (CoA)).

THE ‘LAST SHOT’ RULE

Sometimes in commercial contexts there can be confusion as to who the offeror is and who the offeree. In Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation Ltd (1979) (CoA) the court ruled that in commercial negotiations the contract will be concluded on the terms of the party which submits their terms last. This is called the ‘last shot’ rule.

In this case Butler sent Ex-Cell-O an offer, in the form of a quotation, for delivery of a machine tool. Ex-Cell-O replied, accepting the offer, but on different terms (a counter offer – making them the offeror). Butler then signed and returned Ex-Cell-O’s confirmation tear-off slip. The court ruled that the parties had contracted on Ex-Cell-O’s terms because they had fired the ‘last shot’ which Butler had accepted by signing and returning the slip.

In Tekdata Interconnections Ltd v Amphenol Ltd (2009) the court held that the ‘last shot’ rule could be displaced if the contractual documents indicated a common intention to contract on a different set of terms.

CERTAINTY OF ACCEPTANCE

Where the terms of the offer are too vague a contract will not be enforced by the court and any acceptance will not be valid. In Scammell v Ouston (1941) (HoL) the phrase ‘on hire purchase terms’ was not defined and was therefore too vague to be enforceable.

EXCEPTIONS CERTAINTY OF ACCEPTANCE

However, there will be occasions where an otherwise vague or ambiguous phrase may be given specific meaning by the courts. To give effect to the intentions of the parties, the court can look to standard commercial practice or the previous dealings of the parties to define any ambiguous term. The courts should interpret words in an agreement in such a way as to preserve, rather than destroy, its subject matter (Hillas v Arcos (1932) (HoL)).

Hillas had purchased timber from Arcos. The agreement contained an option to purchase an extra 100,000 units at a discounted rate with the price to be agreed the following year. Arcos refused to honour this, arguing that the term was too ambiguous to be enforceable, it was simply an agreement to agree a price. However, the court disagreed, the term (to set a discounted rate/ price) was objectively certain enough to be enforceable. The ambiguity as to price was because the price of wood fluctuated over time, it was not enough to destroy the agreement all together.

An objective reference to determine the meaning of any phrase is vital. In Baird Textile Holdings v Marks & Spencer (2001) (CoA) the meaning of ‘reasonable’ quantity and price could not be determined by the court because they had no objective criteria by which to judge it. The agreement between the parties had never been formally set down and therefore it was not possible to interpret what the parties common intention was based on that term. The phrase was too ambiguous to create a contract.

KNOWLEDGE OF THE OFFER

The offeree must be responding to a known offer when they accept. They cannot accidentally accept an offer without knowing it exists (R v Clarke (1927) (HC of Australia)).

The Australian government offered a reward for information about a crime. Clarke was a prisoner who provided information but had forgotten about the existence of the reward. Therefore he could not accept the offer.

‘There cannot be assent without knowledge of the offer, and ignorance of the offer is the same thing whether it is due to never hearing of it or forgetting it after hearing’, Higgins J

Another example of this is Gibbons v Proctor (1891) (HC). Gibbons, a police officer, gave information about a crime to a colleague. No reward had been offered at this time. The information provided by Gibbons was passed through several colleagues to the Superintendent. By this time the reward had been offered. The offer had specifically asked for information to be given to the Superintendent and Gibbon’s information only fulfilled this request (despite going via others) after he had knowledge of the offer. Therefore court decided that Gibbons had validly accepted the offer and could receive the reward.

MOTIVE FOR ACCEPTING

The offeree’s motive for accepting is not important as long as they know about the offer (Williams v Cawardine (1833) (HC)).

Mr Cawardine published an advertisement asking for information related to the murder of his brother. Information that lead to a conviction would receive £20. Mrs Williams, after initially giving a statement of little value, decided to give information pertaining to the murderers. One of the murderers was in fact her husband who had severely beaten her and she believed that she was dying. It was argued that she was not motivated by the reward but by the fact that she wanted to clear her conscience before death. The court found that her motive for coming forward with the information made no difference, she had fulfilled the terms of the offer.

COMMUNICATION OF ACCEPTANCE

In order to be valid, acceptance must be communicated to the offeror.

If the acceptance is posted then it is valid at the moment it is posted (see Postal Rule below). If the method of communication is instantaneous then acceptance will be valid upon receipt by the offeror (Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corp (1955) (CoA)).

Acceptance was communicated via telex from Holland and received on the claimant’s machine in London. The court decided that telex was a form of instantaneous communication valid upon receipt (like face-to-face or telephone) and did not follow the Postal Rule which had been applied to telegrams. As such, the contract was formed where it was accepted in England and not in Holland from where it was sent. It was an important decision because it decided in which jurisdiction the contract was completed.

In addition, it was discussed that it is the offeree’s responsibility to do everything reasonably possible to ensure that the message has been received. For example, if a plane flies overhead whilst acceptance is being communicated then the offeree must repeat themselves to make sure the offeror has heard. If they do not then acceptance will not be valid. However, if it is the offeror’s fault that the message is not received (e.g. the offeror’s phone line is bad or their telex machine is out of ink) acceptance is still valid. If it is neither party’s fault then acceptance is not valid.

The overriding principle was confirmed in Brinkibon Ltd v Stahag Stahal (1983) – acceptance will take effect at the point where the offeror can reasonably expect it to have done so IF they have done everything reasonably possible to ensure that the message has been communicated to the offeror.

METHODS OF COMMUNICATION

SILENCE

The offeree’s silence cannot equal acceptance. Silence is not clear enough a response to lead to a valid acceptance (Felthouse v Bindley (1862) (Court of Common Pleas)).

Felthouse offered to buy a horse from his nephew. He said that if he heard no more from his nephew then he would consider the horse his. The horse was already at an auction organised by Bindley. Despite the nephew telling Bindley not to sell the horse, Bindley accidentally sold the horse at auction and the uncle sued Bindley for conversion. The uncle said that he had concluded a contract to buy the horse from his nephew before it was sold and therefore Bindley had no right to sell it. However, the court ruled that he nephew’s silence was not a valid form of acceptance and therefore there had been no valid contract.

EXCEPTIONS

In limited circumstances silence can equal acceptance (Rust v Abbey Life Insurance Co (1979) (CoA)). Rust had some extra money after selling her hotel and wanted to invest the money in Abbey Life property bonds. She filled in an application for the investment and wrote a cheque for the investment amount which she then sent to Abbey Life. Rust received the investment policy documents which she should have signed and returned. She failed to do so and after several months, unhappy with her investment, she tried to argue that as she had never signed and agreed to the policy she could claim her money back. The court held that Rust’s silence and previous conduct indicated acceptance even though she hadn’t returned the signed policy.

In Dresdner Kleinwort Limited & Anor v Attrill & Ors (2013) (CoA) a company announced that it was offering its employees bonuses and that they had approved a ‘guaranteed bonus pool’ to pay these bonuses. Later, they tried to reduce the bonuses to 90% less than what was originally promised. The court said that there was no need for the employees to have ‘accepted’ the original offer in order for the company to be bound by it. The company had the contractual power to give bonuses without needing acceptance of them under the contracts of employment with its employees. By announcing the bonuses, they also implicitly waived the need for acceptance.

CONDUCT AS ACCEPTANCE

The conduct of the offeree can indicate acceptance. In a situation where the offeree says nothing but their conduct indicates that they intend to accept then this can equate to a binding acceptance (Brogden v Metropolitan Railway Co (1877) (HoL)).

Brogden informally supplied coal to the Metropolitan Railway. The two parties decided to create a formal agreement but it was never properly signed. Despite this, the subsequent conduct of the parties (they continued to send and receive loads of coal) constituted acceptance of the formal agreement.

TIMING OF ACCEPTANCE

If the acceptance is sent within normal working hours (circa 9am to 6pm) then it is deemed to have been communicated upon arrival even if it is not read until later (The Brimnes (1975) (CoA)).

A telex was sent within working hours (at 5.45pm) but not read until the following Monday. It was deemed to have been valid upon arrival, even though it hadn’t been read, because the offeree would have expected it to have been read when it arrived.

Note that in this case it was a revocation that was being sent and not an acceptance but the rule applies to both.

COMMUNICATION OUTSIDE OF WORKING HOURS?

If the acceptance is sent outside of working hours it is not officially accepted until the beginning of the next working day. The offeree cannot assume that the offeror will have seen it before then. In Mondial Shipping v Astarte Shipping (1995) (HC) a telex sent at 11.41pm was only valid at the start of the next working day.

The definition of ‘normal working hours’ has been disputed. In Thomas v BPE Solicitors (2010) (HC)an email sent at 6pm on a Friday was deemed to be within working hours partly because the previous correspondence had discussed the need for the transaction to be completed on that day. It seems that the specific circumstances of the case will be applied to determine whether the acceptance should have been read by the offeror but the law remains uncertain.

THE POSTAL RULE

Unlike instantaneous methods of communication if the offeree posts their acceptance to the offeror then it is valid at the moment it is posted (Adams v Lindsell (1818) (HC)). This is known as the Postal Rule and it is an exception to the general rule that acceptance is valid upon receipt.

THE POSTAL RULE

There are four conditions attached to the postal rule:

1. It applies only to acceptances

(not offers or revocations). |

|

|

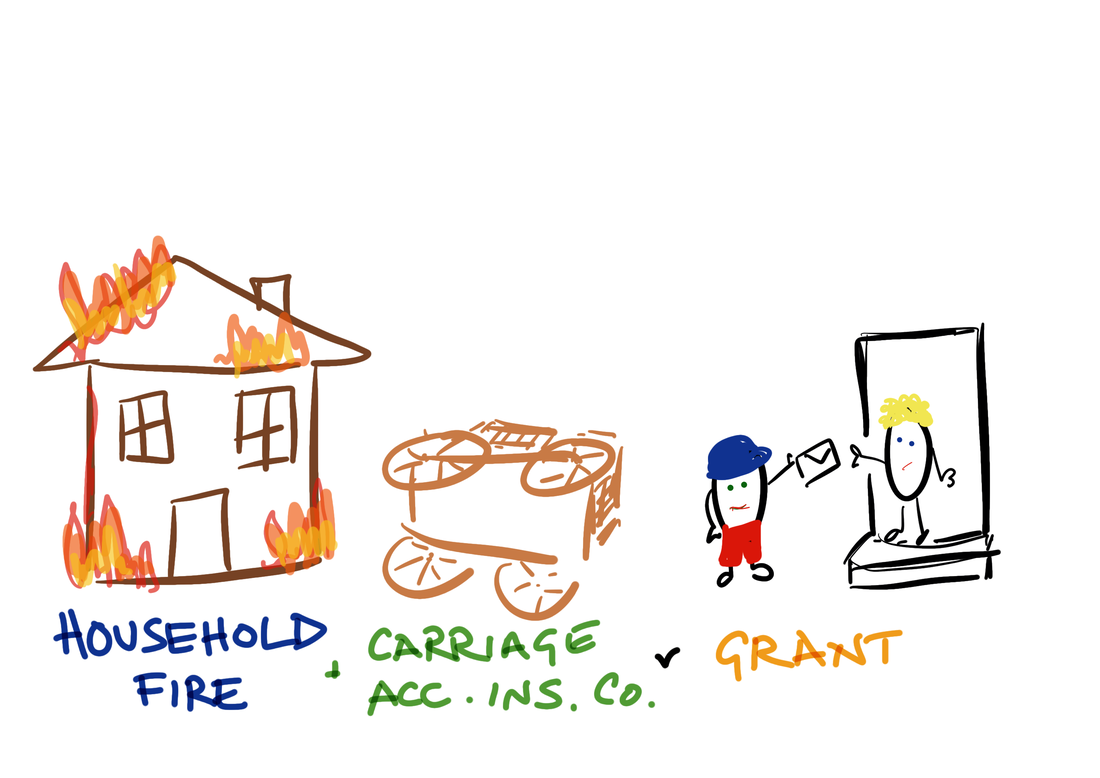

2. The acceptance letter must be properly posted, it can’t be given to a postman. If it doesn’t arrive because of a fault of the offeree then acceptance will not be valid. If it doesn’t arrive for a reason outside of the offeree’s control (e.g. delayed post) then it will still be valid (Household Fire & Carriage Accident Insurance v Grant (1879) (CoA)). |

|

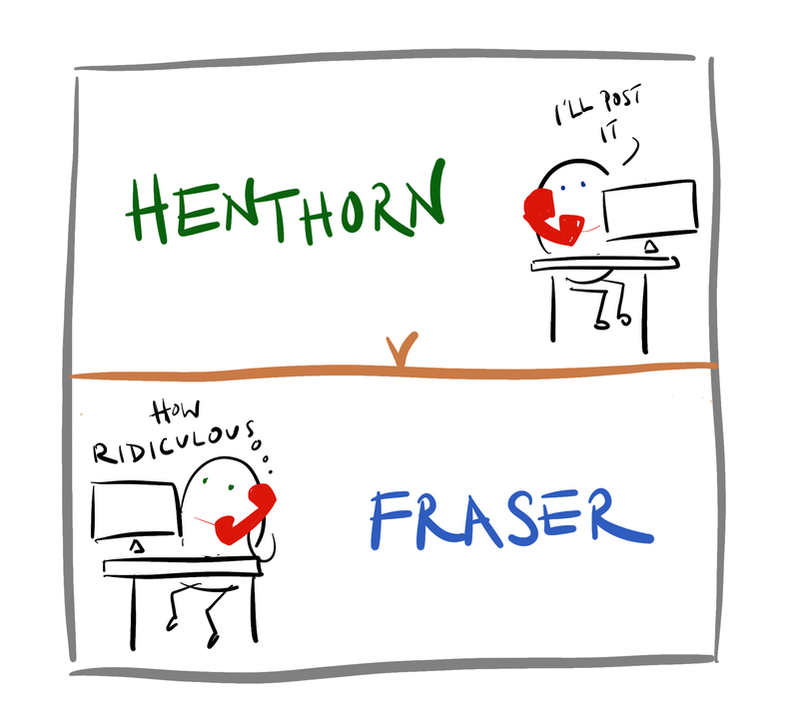

3. It only applies when reasonable to do so (Henthorn v Fraser (1892) (CoA)).

E.g. If the two parties reside in the same building or the offer was sent by email it may not be reasonable to accept by post. |

|

|

|

4. The offeror can exclude the postal rule expressly or by implication (Holwell Securities v Hughes (1974)).

In this case the term that acceptance should be made ‘exercisable by notice in writing’ was enough to exclude the postal rule as it implied that the offeror wanted actual communication of the acceptance in order for it to be valid. Holwell’s acceptance was lost in the post and never arrived.

If acceptance is still sent by post, even though the postal rule was excluded, it will be valid upon receipt.

|

An acceptance sent by post can be revoked by a faster method of communication (Countess of Dunmore v Alexander (1830)). However, this was only expressed in an obiter dicta in a Scottish case and has never been followed since.

ACCEPTANCE OF UNILATERAL OFFERS

Acceptance of a unilateral contract is the completion of the specified act by the offeree (Daulia v Four Millbank Nominees (1978) (CoA)). There is no obligation to communicate acceptance before beginning the act.