JUMP TO:

FAMILY AGREEMENTS: Balfour v Balfour | Merritt v Merritt | Jones v Padavatton | Parker v Clark | Snelling v John G Snelling

SOCIAL AGREEMENTS: Wilson v Burnett | Simpkins v Pays | Sadler v Reynolds

COMMERCIAL AGREEMENTS: Bunn & Bunn v Rees & Parker | Edwards v Skyways | Volumatic v Ideas for Life | Rose & Frank v Crompton Bros | Jones v Vernon’s Pools | Blue v Ashley | MacInnes v Gross | Anchor 2020 v Midas Construction

ADVERTS: Esso v Customs & Excise | Leonard v Pepsico

REVISE | TEST

INTENTION TO CREATE LEGAL RELATIONS

For there to be a valid contract both parties must have intended to create legal relations.

DOMESTIC & SOCIAL AGREEMENTS

In domestic and social agreements the presumption is that there was no intention to create legal relations. The presumption serves as a tool to keep contracts in the commercial sphere and out of the domestic realm. In order to rebut this presumption clear evidence will be needed that the parties did intend to be bound. The presumption can be rebutted, the court will look at the certainty of the terms, the seriousness of the agreement and the reliance of the parties to decide whether they intended to be bound.

MARRIED COUPLES

The general rule is that there can be no intention to be bound between married couples because any agreement is based on ‘natural love and affection’, Atkin LJ (Balfour v Balfour (1919) (HC)).

Whilst they were still married Mr Balfour had to move abroad for work but Mrs Balfour could not for health reasons. He promised to pay her an allowance. When they separated she tried to enforce this promise. The court found that there was no agreement because, as husband and wife, they lacked intention to be legally bound.

There is a public policy reason that underlies this. If the presumption of intention was allowed to stand in domestic situations, the courts would be inundated with potential claims whenever contractual disputes had arisen between couples.

EXCEPTIONS

In Merritt v Merritt (1970) the presumption was rebutted because the couple had already separated when their agreement was made. In these circumstances the parties did intend to be legally bound because they were no longer in a domestic situation. When couples are separated the nature of their relationship changes and the couple ‘bargains keenly’, meaning they start negotiating about the division of assets and maintenance payments.

OTHER FAMILY AGREEMENTS

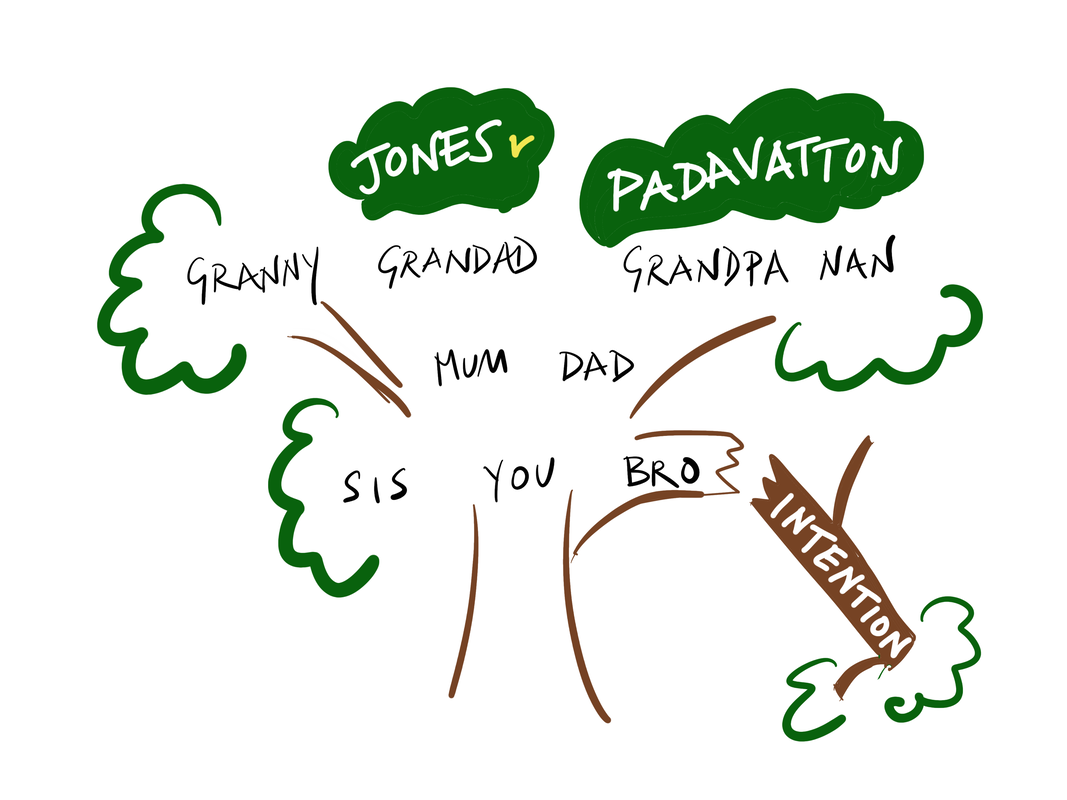

The same presumption applies to agreements between other family members (Jones v Padavatton (1969) (CoA)).

A mother offered to pay her daughter an allowance if she gave up her job in America to train for the bar in England and then work in Trinidad. The daughter expected the allowance to be in US dollars but the mother paid in Trinidadian dollars. The daughter and her son could not survive on the amount so the mother bought a house, part of which they lived in and part of which was rented out to cover the daughter’s expenses. After five years the daughter had married but still not passed her exams, the two fell out and the mother tried to evict the daughter. The court held that there was insufficient evidence to rebut the presumption of no intention between family members and the daughter had to leave.

However, in Parker v Clark (1960) (HC) the presumption was rebutted. An elderly couple (the Clarks) asked their niece and her husband (the Parkers) to sell their house and move in with them, offering in return to leave them the house in their will. The Parkers sold their house as a result and used the money to purchase their daughter a flat. After the Parkers moved in with the Clarks, the two couples fell out and the Clarks tried to evict the Parkers. The Parkers said that this would be a breach of contract. The seriousness of the agreement and the clear language used between the parties showed an intention to be bound that rebutted the presumption.

Similarly in Snelling v John G Snelling (1973) (QB), it was held that three brothers who were directors of a family company and who had entered into an agreement about the running of the company, intended to create legal relations. As the agreement was intended to be for the benefit of the company, there was an intention that the agreement should be upheld.

SOCIAL AGREEMENTS

Agreements between friends and colleagues are governed by the same presumption of no intention to be bound.

Compare the cases below…

|

|

|

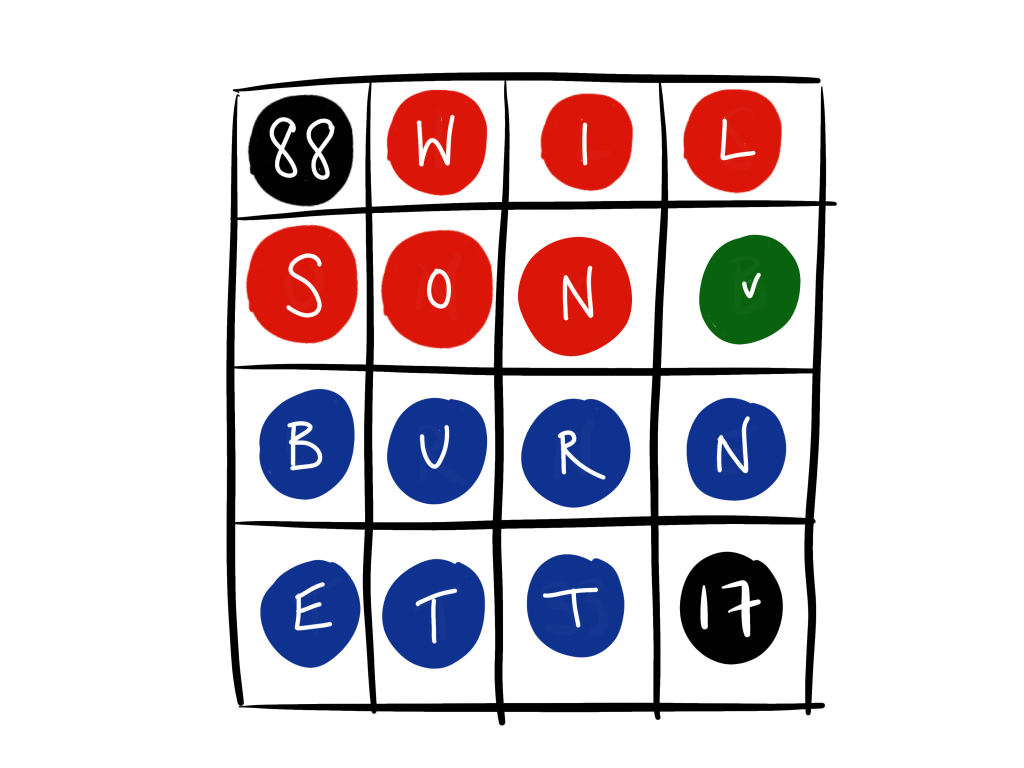

| In Wilson v Burnett (2007) (CoA) the court did not find intention between three work colleagues who played bingo together one evening. Two of them claimed that there had been an agreement to share their winnings but the third, who had won, disputed this. The ‘bare-bones account’ of their casual conversation was not sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption. |

In contrast, in Simpkins v Pays (1955) (Assizes) a grandmother, granddaughter and lodger regularly entered a weekly competition. The grandmother’s name was always the only one on the coupon but they took it in turns to pay for, and post, the coupon. When they won the grandmother refused to share the winnings. The court felt that their arrangement went beyond the ‘sort of rough and ready statement’ usually made between family and friends and therefore there was intention to be bound. |

Some cases are a mixture of social and commercial. In these circumstances the presumption is still that there is no intention to be bound, however the weight of evidence needed to rebut the presumption is less than in a purely commercial situation and the onus will be on the party which claims that a contract has been legally formed. In Sadler v Reynolds (2005) (HC) friends discussed that one would ghost write the other’s autobiography. The court decided that the subsequent actions of the parties did rebut the presumption and found intention to create legal relations.

COMMERCIAL AGREEMENTS

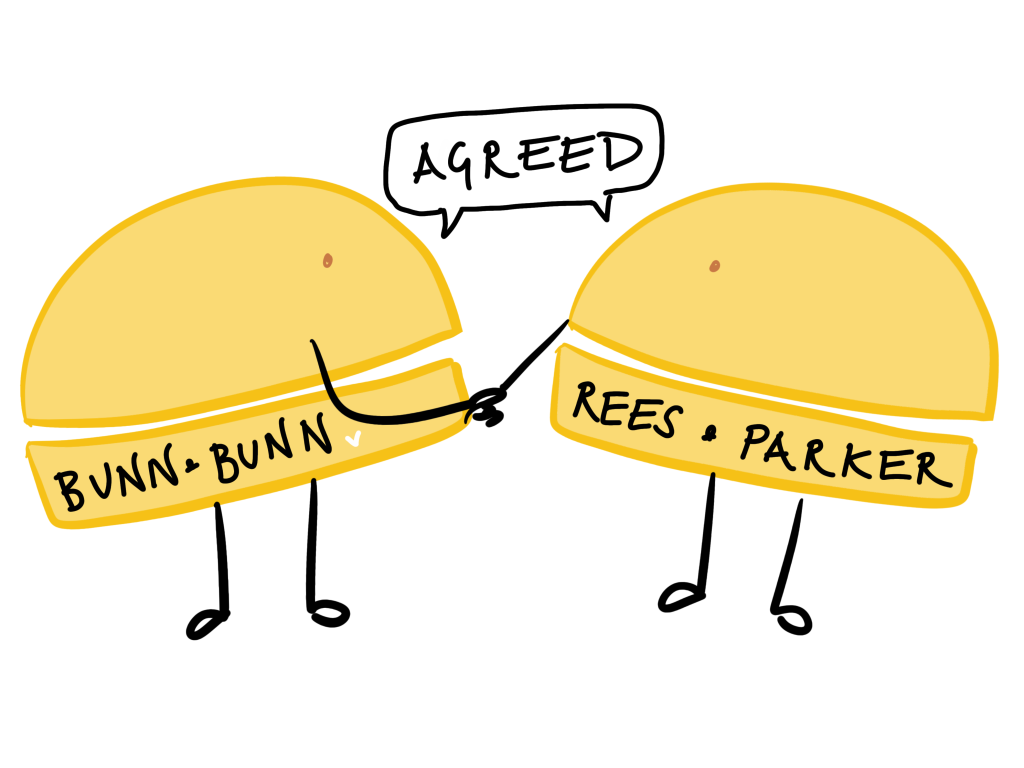

In commercial agreements the presumption is that the parties did intend to be legally bound (Bunn & Bunn v Rees & Parker (2002)).

In this case the fact that the parties had compiled a signed document setting out terms was sufficient to find intent even though there were still fine details to be worked out.

REBUTTING THE PRESUMPTION

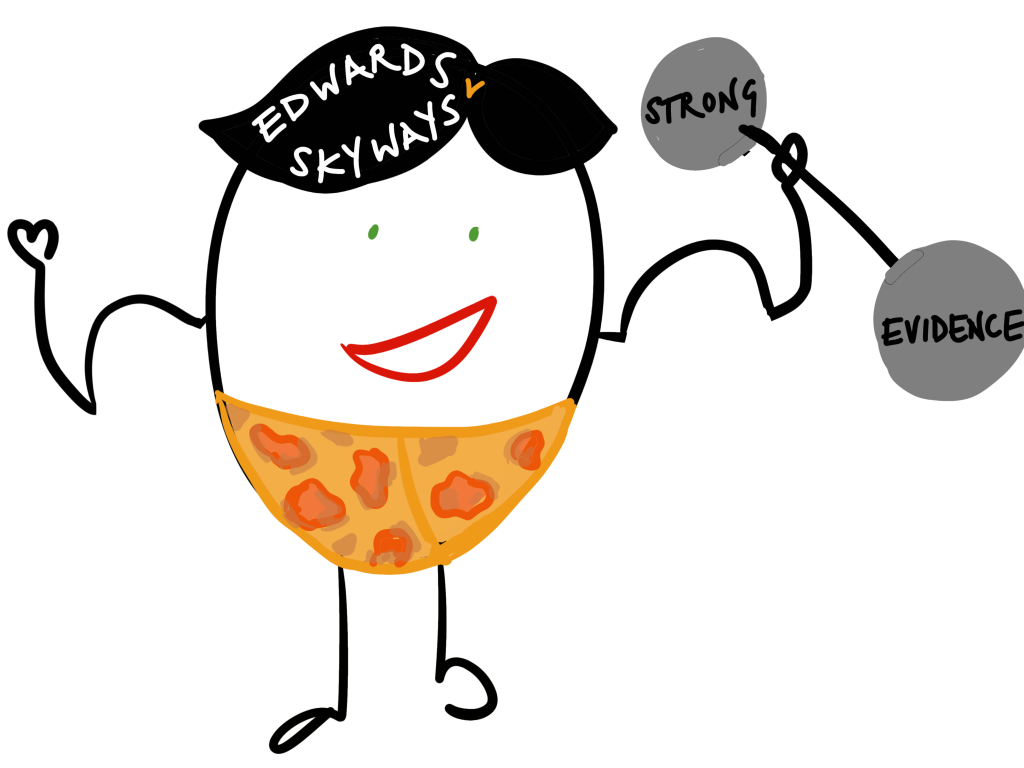

The presumption can be rebutted but strong evidence will be required and the onus will be on the party attempting to rebut the presumption (Edwards v Skyways (1964) (HC)).

Edwards was being made redundant by Skyways. If Edwards withdrew his pension contributions Skyways offered to pay him the equivalent in an ex gratia (voluntary) payment. He did so but Skyways then tried to go back on their offer, claiming an ex gratia payment was not binding. The court decided that because of the commercial context the presumption to be bound had not been rebutted by this evidence and Skyways owed Edwards the payment.

Also see the more recent case of Volumatic Ltd v Ideas for Life Ltd (2019)(HC). A rare instance where an express, written document was found to be non-binding based on the Court’s interpretation of the parties’ intentions. The document was found to be only a record of the consensus reached between the parties at a particular moment beyond which it had no contractual force. In addition, neither party had sought to rely on it at all in the 11 years between its creation and the dispute.

EXCLUDING THE PRESUMPTION

The presumption of intention can be avoided if the parties expressly state in their agreement that there is no intention to be legally bound (Rose & Frank v Crompton Bros (1925) (HoL)). These are often called honourable pledge clauses or ‘honour clauses’.

In Jones v Vernon’s Pools (1938) (Assizes) Jones sent in two entry coupons for a sales promotion run by Vernon Pools. the football pools. The coupons stated that they were ‘binding in honour only’. One of them was a winning coupon but Vernon’s Pools claimed that it had never arrived. Jones argued that there was a binding contract but the wording on the coupon meant that there was no intention to be bound.

INTENTION OF THE PARTIES

If necessary the court will consider the intentions of the parties based on what was communicated between them by words or conduct. This is an objective, and not a subjective, test.

The recent cases of Blue v Ashley (2017) (HC) and MacInnes v Gross (2017) (HC) are good examples. In both cases promises of large payments between business associates were made over boozy meals. Both offerors successfully argued that the social situation, the consumption of alcohol, the lack of any formal written agreement and the over-the-top nature of the offers proved that there was no real intention to be bound.

Also consider the case of Anchor 2020 v Midas Construction (2019) (HC) in which the court held that objectively there was a common intention to be bound even though full contractual formalities had not been completed, e.g. the contract had only been signed by one party. The fact that one party had already begun to perform its contractual obligations went towards the finding of intention.

ADVERTS

Adverts are generally invitations to treat and often include statements that are ‘mere puff’ and are not expected to be taken as legally binding. Unilateral offers are the exception but there must still be intention to create legal relations. In Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893) (CoA) the fact that the company had placed £1,000 in a bank account showed sufficient intention. If the promise is sufficiently clear then it will be legally binding (see also Bowerman v ABTA (1996) (CoA)).

However, the case of Esso Petroleum v Commissioners of Customs & Excise (1976) (HoL) highlights how each case will rest on its facts. Esso offered a free World Cup coin to anyone who bought 4 gallons of petrol. There was a dispute as to the nature of the offer for tax purposes. The court found intention based on the commercial context of the offer and the extra profit that Esso intended to make through the scheme. However, the dissenting minority found no intention because of the specific language of the offer (the offer of ‘free gifts’), the small value of the coins and the fact that most buyers would never consider bringing legal action if they were not given a coin.

The seriousness of the offer in an advert will also be taken into consideration. In the American case of Leonard v Pepsico (1999) a Pepsi advert suggested that anyone who collected 7,000,000 Pepsi Points could claim a Harrier Jump Jet. Unfortunately for Leonard, who did collect this huge number, the court held that the ‘offer’ was mere advertising puff and no reasonable person could have really believed that Pepsi would give them a jump jet.