JUMP TO:Foakes v Beer | Implications of Williams v Roffey: Re Selectmove | Rock Advertising v MWB Business Exchange Centres

EXCEPTIONS: Pinnel’s Case | Vanbergen v St Edmund Properties

PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL: Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House | Woodhouse v Nigerian Product Marketing | Ajayi v Briscoe | W J Alan v El Nasr | Combe v Combe | D & C Builders v Rees | Tool Metal Manufacturing v Tungsten Electric

REVISE | TEST

PART PAYMENT OF DEBT & PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL

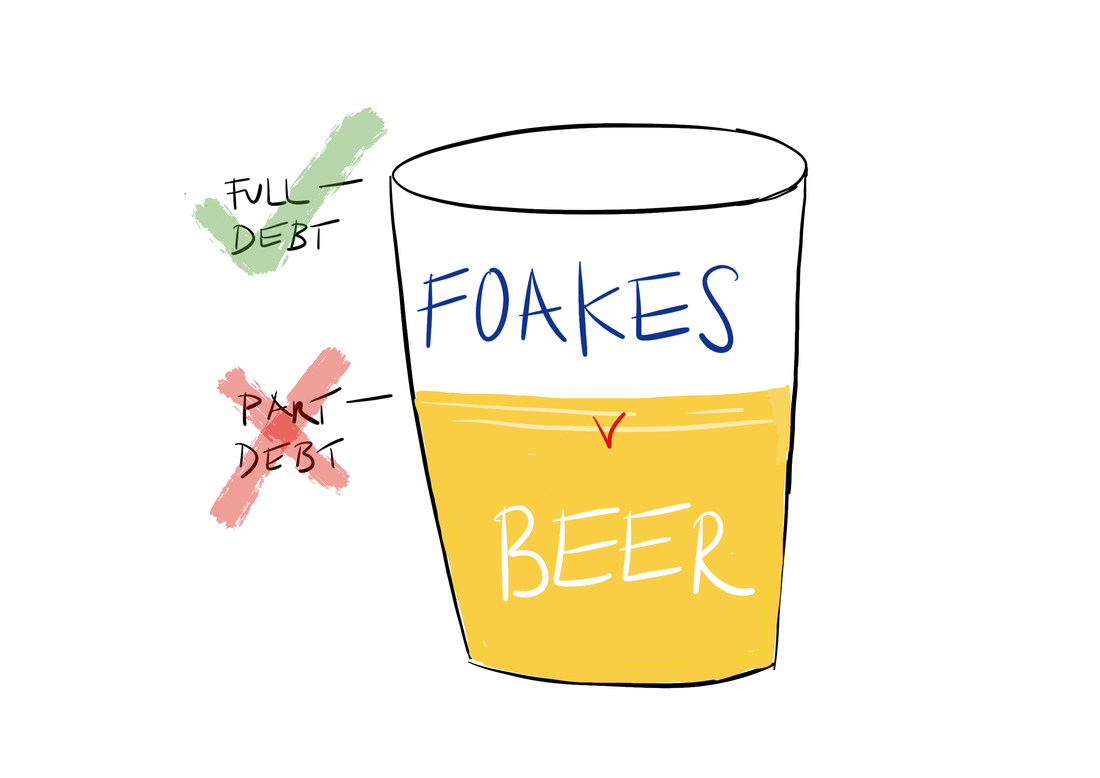

The general rule is that part payment of a debt (or an alteration in the terms of payment) is not good consideration. Part payment is not sufficient consideration for the other party’s promise to accept less. Therefore, anyone promising to accept part payment of a debt is not bound by that promise.

CONSIDERATION NEEDED

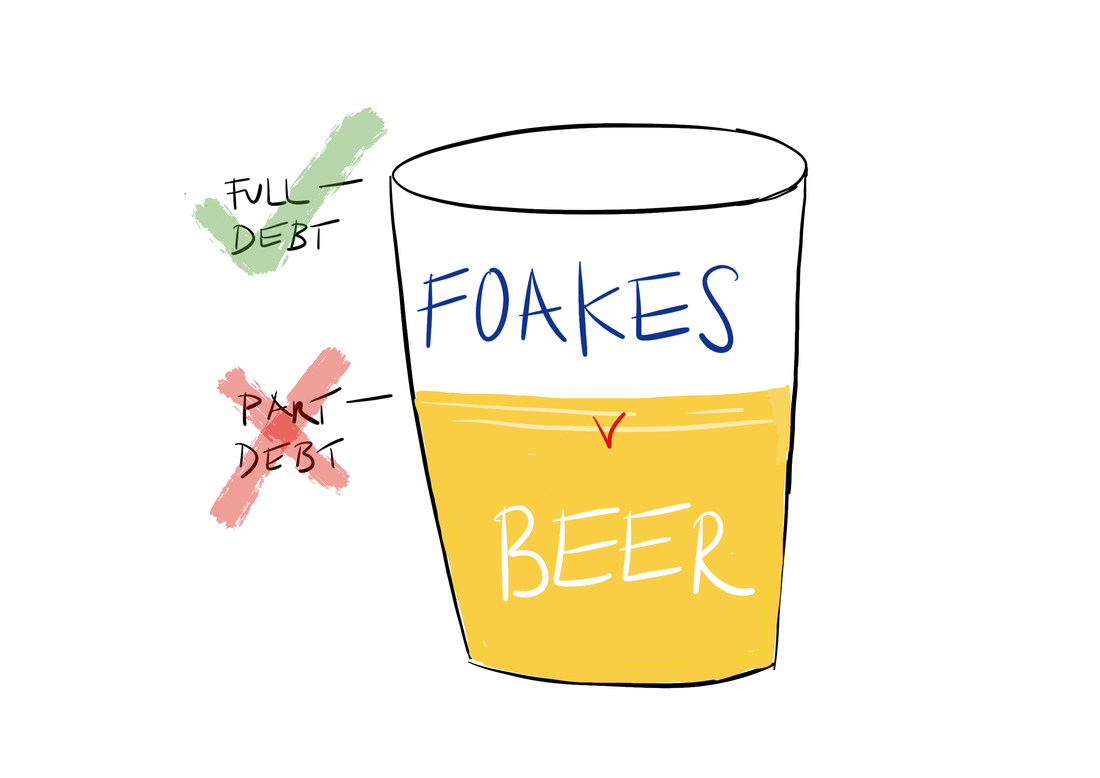

If the debtor wants to vary their obligation to pay they must provide fresh consideration. The authority for this principle is found in Pinnel’s Case (1602) (Court of Common Pleas) and has subsequently been confirmed by the House of Lords in the case of Foakes v Beer (1884) (HoL).

Dr Foakes owed Mrs Beer money. He was unable to pay all of it at once so he offered to pay her in instalments. She agreed and promised not to enforce the debt against him if he kept up with the payments. When he had repaid his debt she sued him for payment of the interest. The court found that Mrs Beer’s promise not to sue had not been supported by any fresh consideration from Dr Foakes and therefore he owed her the interest.

The decision in Foakes v Beer (1884) has been heavily criticised and was even unpopular with the judges who made it (one of them even wrote a dissenting speech which he decided not to give). However, they felt bound by Pinnel’s Case with no way to distinguish the facts of Foakes v Beer and since then its precedent as a House of Lords decision has meant that it has remained good law.

However, some may argue that receiving payment of some of the debt is better than not being paid at all, which could offer a practical advantage to a creditor. How do we reconcile Foakes v Beer with the reasoning of Williams v Roffey?

IMPLICATIONS OF WILLIAMS v ROFFEY

The implications of the landmark judgment in Williams v Roffey (1990) (CoA) on the decision in Foakes v Beer (1884) (HoL) were explored in Re Selectmove (1995) (CoA). Selectmove owed taxes to the Inland Revenue and their offer of paying in instalments had been accepted. However, the Inland Revenue changed their mind and sued for the full payment. Despite recognition that the creditor would gain a benefit (full payment over time rather than only part payment) a promise to accept a varied payment was not considered sufficient consideration. Peter Gibson LJ argued that he was bound by precedent; there was no way to distinguish Re Selectmove from Foakes v Beer (a House of Lords case) and the judges in Williams v Roffey (a Court of Appeal case) had never mentioned how their decision would affect a promise to pay less. If the court held that the promise was sufficient consideration then the decision in Foakes v Beer would be ‘without any application’. Therefore the Williams v Roffey principle does not apply to promises to pay less or alter payment, only promises to pay more. Gibson LJ believed that to extend the rule in such a way should be decided by a higher court or even Parliament itself.

In the more recent case of Rock Advertising Limited v MWB Business Exchange Centres Limited (2018) (SC), the parties agreed to a revised payment schedule under a licence agreement. The oral agreement was to defer part of the payments and to spread the accumulated arrears over the remainder of the licence term. However, the licence agreement contained a “no oral modification” clause, meaning that parties needed to follow strict steps in order to vary the contract and these steps were not followed. The first judge found that the oral agreement for a revised payment schedule was supported by consideration as there were “practical advantages” to the creditor. However, on appeal to the Supreme Court it was found that the “no oral modification” clause was still valid and must be complied with. Therefore the oral agreement for a revised payment schedule was not enforceable. The Supreme Court did not need to decide on the issue of “practical advantages” but Lord Sumption said the following about the application of Foakes v Beer:

“The reality is that any decision on this point is likely to involve a re-examination of the decision in Foakes v Beer. It is probably ripe for re-examination. But if it is to be overruled or its effect substantially modified, it should be before an enlarged panel of the court and in a case where the decision would be more than obiter dictum.”

PINNEL’S CASE

A common law exception to this rule is if the debtor can show that, although they only part-paid their debt, they gave something else to make up the difference (Pinnel’s Case (1602) (Court of Common Pleas)).

‘the gift of a horse, hawk, or robe, etc. in satisfaction is good. For it shall be intended that a horse, hawk or robe might be more beneficial to the plaintiff than the money’, Lord Coke, Pinnel’s Case (1602)

As long as the creditor has freely agreed to accept the ‘horse, hawk or robe’ in exchange for full payment then this will be accepted by the courts. In Pinnel’s Case the creditor accepted less in exchange for being paid earlier than was required.

In Vanbergen v St Edmund Properties (1933) (CoA) the fact that the debtor paid at a different location than he was obligated to do so, at the creditor’s request, was sufficient consideration for a promise to pay less. The creditor requested that the payment be made at his solicitor’s office.

PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL

Promissory estoppel is an equitable principle that stops one party from going back on a promise (such as promising to accept part payment) if it would be inequitable to do so. As an equitable remedy it is governed by the rules of equity.

Promissory estoppel was first properly defined in Lord Denning’s (then styled Denning J) obiter dicta in Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd (1947) (HC).

High Trees had taken out a lease on a block of flats from Central London Properties. The outbreak of war meant that High Trees struggled to fill the flats so Central London agreed to reduce the rent. When the war ended High Trees was able to rent out more flats so Central London requested a return to full rent and took High Trees to court to recover the full rent from the end of the war onwards. Denning J ruled that as the reason for offering the lower rent (the war) had ended and High Trees owed Central London full rent for the period since the end of the war. However, in obiter comments he said that had they asked for the full balance during the war years they would have been estopped from doing so because to go back on that promise would have been inequitable.

Denning based his comments on the decision in Hughes v Metropolitan Railway (1877) (HoL). Hughes (the lessor) gave Metropolitan Railway (the lessee) six month’s notice in which to repair their property. In response Metropolitan Railway began negotiations with Hughes regarding buying the remaining lease. Negotiations broke down and Hughes enforced the six month notice period taking Metropolitan Railway to court when the repairs were not done. The House of Lords found that there was an implied promise that the notice would be suspended during negotiations even though that promise was unsupported by consideration. It was inequitable for Hughes to have breached that promise.

There are four rules of promissory estoppel, developed by Lord Denning in subsequent cases.

EXISTING AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE PARTIES

There must be an existing agreement which is followed by a clear and unequivocal promise to not enforce existing contractual rights (Woodhouse A.C. Israel Cocoa Ltd v Nigerian Product Marketing Co Ltd (1972) (HoL)).

The two companies had for years traded cocoa beans for Nigerian pounds. In a letter Woodhouse asked NPM if they could instead pay in sterling. NPM replied stating that they could. At this point one Nigerian pound was worth one pound sterling. When the exchange rate changed a dispute arose between the two parties as to what NPM’s response actually meant. NPM argued that it meant Woodhouse could pay the equivalent amount in sterling. Woodhouse argued that it meant they could pay one pound sterling for every Nigerian pound owed. The court held that the letter was too imprecise to be the basis for promissory estoppel.

For a claim in promissory estoppel to succeed, the ‘promise’ or representation must be reasonably clear and definite as to the terms of the contract that are being waived.

ALTER POSITION IN RELIANCE

The promisee must alter their position in reliance on the promise (Ajayi v Briscoe (Nigeria) Ltd (1964) (PC Nigeria)).

Ajayi sold lorries on hire purchase to Briscoe but the lorries needed servicing. Ajayi agreed that Briscoe could withhold payments whilst they were being serviced. When the lorries were ready Ajayi demanded payment. Briscoe argued that they had not been given notice that the lorries were ready and tried to use promissory estoppel as a defence. However, the court held that as Briscoe had not altered their position in reliance on the promise from Ajayi promissory estoppel could not be used.

It is not necessary for the alteration to have been detrimental to the promisee (W J Alan Co v El Nasr (1972) (CoA)). In this case the buyers of Kenyan coffee beans, El Nasr, were able to use the defence of promissory estoppel even though they had benefited from the alteration (buying in pound sterling rather than Kenyan shilling). As Lord Denning said, the promisee simply “must have been led to act differently from what he otherwise would have done”, it is not necessary for that change to have been detrimental.

SHIELD NOT SWORD

The doctrine must only be used as a defence and not a cause of action – ‘promissory estoppel is a shield not a sword’ (Combe v Combe (1951) (CoA)).

A husband had promised to make payments to his estranged wife but then didn’t. The wife brought an action to enforce the promise invoking promissory estoppel but was unable to do so because she was using promissory estoppel as a cause of action rather than as a defence (a sword and not a shield).

‘The principle does not create new causes of action where none existed before. It only prevents a party from insisting upon his strict legal rights when it would be unjust to allow him to enforce them.’

Denning LJ, Combe v Combe (1951)

NOT INEQUITABLE TO RENEGE

It must not be inequitable for the promisor to go back on their promise (D & C Builders v Rees (1996) (CoA)). In other words, if the court deem it to have been equitable for the promisor to renege on their promise then promissory estoppel cannot be used to stop them going back on that promise.

D&C Builders had completed some construction work for Mr and Mrs Rees. They owed the builders £400 but refused to pay. Knowing that the builders were in financial difficulties Mrs Rees offered to pay them £300 to settle the bill which the builders unwillingly agreed to, left with no other choice. When D&C took Rees to court for the money owed, she tried to use promissory estoppel as a defence. It failed because, even though D&C had promised to accept less, they had not done so willingly and freely, Mrs Rees had taken advantage of their financial position. Therefore, it was not inequitable for D&C to renege on their promise to accept £300 and Mrs Rees could not rely on promissory estoppel.

EFFECT OF PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL

Promissory estoppel either extinguishes or suspends contractual rights.

For suspended contractual rights to be reestablished reasonable notice must be given to the other party (Tool Metal Manufacturing Co v Tungsten Electric Co (1955) (HoL)).

Tool Metal granted Tungsten Electric the license to manufacture and sell their patented alloys. If they manufactured over a certain quantity Tungsten Electric had to pay Tool Metal compensation. During WWII Tool Metal agreed to forgo these compensation payments. After the war Tool Metal sued for the unpaid compensation payments but were estopped from doing so because Tungsten Electric had not been given reasonable notice that the original contractual rights were to be reestablished. Ten years later Tool Metal brought another case against Tungsten Electric. This time they were successful, the court agreed that the first case had given Tungsten Electric reasonable notice that Tool Metal wished to reestablish the original contractual rights.