JUMP TO: DAMAGES – Robinson v Harman – EXPECTATION LOSS – Radford v De Froberville | Ruxley Electronics & Construction v Forsyth | Darlington Borough Council v Wiltshier Northern | James v Hutton and J Cook & Sons | Chaplin v Hicks – NON-PECUNIARY LOSS – Addis v Gramophone | Jarvis v Swans Tours | Diesen v Samson | Heywood v Wellers | Shaw v Leigh Day | Farley v Skinner | Ruxley Electronics & Construction v Forsyth – RELIANCE LOSS – Anglia Television v Reed | Omak Maritime Ltd v Mamola Challenger Shipping Co | CCC Films (London) Ltd v Impact Quadrant Films | McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission

DAMAGES

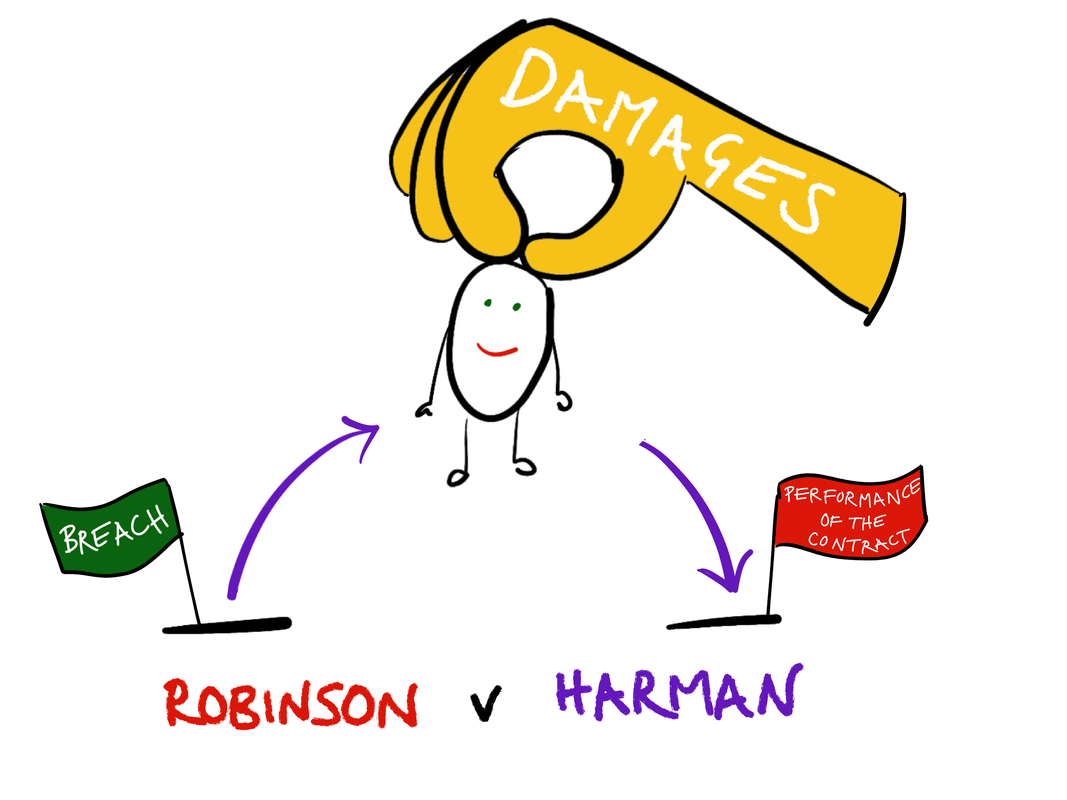

Damages is the payment of money to compensate the innocent party for any loss suffered as a result of the breach. Damages are not designed to be a punishment for the defendant which means that where the claimant suffers no loss they will only be awarded nominal damages.

The aim of damages is to compensate the innocent party and place them in the position they would have been in had the contract been performed (Robinson v Harman (1848) (Court of Exchequer)).

‘…where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract, he is, so far as money can do it, to be placed in the same situation, with respect to damages, as if the contract had been performed.’ Parke B, Robinson v Harman

CALCULATING DAMAGES

If damages are compensatory, the next question is: for what is the claimant entitled to be compensated? There are several different mechanisms that the courts can use to calculate damages.

EXPECTATION LOSS

Pecuniary expectation losses can be calculated as Difference in Value, Cost of Cure or Loss of Opportunity.

Non-pecuniary expectation losses can be calculated as distress and disappointment or a loss of amenity. |

RELIANCE LOSS

If losses are too speculative the courts will award damages based on what the claimant lost in reliance upon the contract. |

PECUNIARY EXPECTATION LOSS

The expectation loss is a calculation of damages based on placing the innocent party in the same position he would have been in had the defendant performed his promise. This is supported by the justification that a binding promise creates an expectation of performance, and the remedy granted for the breach of such a binding promise must protect that expectation.. This can be the difference in value, cost of cure or loss of opportunity.

DIMINUTION (DIFFERENCE) IN VALUE

The court considers the loss to the claimant’s overall wealth attributable to the breach (the ‘diminution in value’ measure). The court evaluates the difference in the market value between what the claimant contracted to receive and what they actually ended up receiving.

COST OF CURE

The court can also award the cost of cure. This is an award of damages that covers the cost of remedying the defect or obtaining substitute performance.

In Radford v De Froberville (1977) (HC) the claimant sold part of his land, a plot in his garden, to the defendant for development. The sale agreement required that the defendant would build a boundary wall according to certain specifications so that the plot would be separated from the rest of the garden. The defendant was unable to develop the plot herself, so she sold the plot to a third party under the same agreement. This third party also failed to develop the plot and did not build a boundary wall. As a result, the plot became very overgrown and attracted trespassers who had open access to the claimant’s property. The claimant therefore sued the defendant for breach of contract. The defendant tried to argue that the claimant had suffered no real loss, just inconvenience. The court held that the claimaint was entitled to claim damages for breach of contract which would compensate him for the cost of carrying out on his own land, as nearly as possible, that which the defendant had failed to do.

COST OF CURE OR DIMINUTION IN VALUE?

The presumptive measure of damages in building contracts is the cost of cure (Darlington Borough Council v Wiltshier Northern Ltd (1955) (CoA)). However, as shown in Ruxley Electronics & Construction v Forsyth (1995) (HoL) this prima facie right to the cost of cure is displaced, usually in favour of a diminution in value measure where:

- performance in specie is now impossible,

- the claimant does not in fact intend to obtain the promised benefit,

- the cost of obtaining performance is entirely disproportionate to the claimant’s legitimate interest.

|

Forsyth contracted with Ruxley to build a swimming pool in his garden. The pool was significantly shallower than what had been ordered so Forsyth sought damages for breach of contract. However, the pool was sufficiently deep to swim and dive safely into, which meant the difference in value was £0 but the cost of cure (i.e. to remove and rebuild the pool) was over £21,000. The court felt that it was unreasonable to award the cost of cure as the amount was out of proportion to the loss suffered by Forsyth but that Forsyth should receive £2,500 for loss of amenity.

In James v Hutton and J Cook & Sons Ltd (1950) (CoA) the tenant had made alterations to the front of the shop. The tenancy agreement had a clause stating that if any changes were made to the shop the premises must be returned to the pre-existing condition when the tenancy ended. The tenant did not restore the front of the shop and breached the agreement. The court said that there was no evidence that the premises would be any better if restored. Lord Goddard CJ in the Court of Appeal said it would be a ‘sheer waste of money’ to do so and instead awarded nominal damages.

LOSS OF OPPORTUNITY

It is not always possible to know exactly what the loss caused by a breach of contract would have been, losses may be speculative. In these circumstances, if it is reasonably possible to calculate damages, the courts can award for loss of opportunity (Chaplin v Hicks (1911) (CoA)).

Hicks, a well-known actor, advertised a beauty contest. The winners were to be given acting work. Chaplin entered and made it through to the last round but the letter instructing her where and when to attend never arrived. The court awarded her damages of £100 for the loss of opportunity even though it was speculative whether she would have won anything had she been given the correct information and the opportunity to attend the final.

Just because the loss is speculative does not mean that the courts will not award damages on an expectation basis. ‘The fact that damages cannot be assessed with certainty does not relieve the wrongdoer of the necessity of paying damages for his breach of contract’, Vaughan Williams LJ, Chaplin v Hicks

NON-PECUNIARY EXPECTATION LOSS

Non-pecuniary loss covers any loss that is not financial. Traditionally only damages for physical, rather than mental, distress were awarded by the courts (Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd (1909) (HoL)).

Mr Addis had been fired from his job in what he claimed was a ‘harsh’ and ‘humiliating’ fashion causing him distress and damage to his reputation. The House of Lords refused to make an award for damages on the basis of mental distress and instead ruled that damages were limited to his lost wages and any loss of commission.

RECOVERY FOR DISTRESS OR DISAPPOINTMENT

However, since then the courts have created certain exceptions to this rule. Where the object of the contract was to provide pleasure, relaxation, peace of mind or freedom from molestation and the breach prevented this from happening then damages can be awarded for distress or disappointment. The case of Jarvis v Swans Tours (1973) (CoA) serves as a prime example.

Jarvis booked a ‘houseparty holiday’ in a ski resort. There were numerous problems with the vacation and it did not live up to the description advertised in the holiday brochure. At the first instance Jarvis was awarded half of what he paid for the holiday on the basis that he had only received half of the facilities promised. He appealed and was awarded a larger sum for the lack of facilities and ‘the loss of entertainment and enjoyment which he was promised’.

Other examples include Diesen v Samson (1971) (Sheriff Court) in which a wedding photographer who failed to turn up to a client’s wedding had to pay damages for the bride’s distress at not having any professional wedding photos. In Heywood v Wellers (1976) (CoA) a firm of solicitors who were hired to bring proceedings to restrain a man who had been molesting the claimant failed to do so, leading to the continuation of the molestation. The claimant was able to sue for mental distress and upset. Also see the more recent case of Shaw v Leigh Day (2017) (HC).

PLEASURE NOT SOLE PURPOSE

Pleasure does not have to be the sole purpose of the contract (Farley v Skinner (2001) (HoL)).

Skinner had been employed to survey a house, that Farley wanted to buy, with specific instructions to survey the noise caused by planes coming in and out of Gatwick which was 15 miles away. Skinner’s report stated that ‘we…think it unlikely that the property will suffer greatly from such noise’. In fact the noise from the aircraft was severe and especially affected Farley’s enjoyment of the house’s generous outdoor space. Although the sole purpose of the survey was not enjoyment the House of Lords clarified that it is sufficient that it constitutes a ‘major or important’ element.

Farley was awarded £10,000. This was not challenged by the House of Lords but the size of the award was remarked upon and the court stated that this should be considered at the upper limit of awards for this type of loss, as per Lord Steyn ‘awards in this area should be restrained and modest’.

LOSS OF AMENITY

If there has been no financial loss by the claimant and cost of cure would not be appropriate the courts have also made awards for loss of amenity, also called the ‘consumer surplus’ (Ruxley Electronics & Construction v Forsyth (1995) (HoL)).

Forsyth contracted with Ruxley to build a swimming pool in his garden. The pool was significantly shallower than what had been ordered so Forsyth sought damages for breach of contract. However, the pool was sufficiently deep to swim and dive safely into, which meant the difference in value was £0 but the cost of cure (i.e. to remove and rebuild the pool) was over £21,000. The court felt that it was unreasonable to award the cost of cure as the amount was out of proportion to the loss suffered by Forsyth but that Forsyth should receive £2,500 for loss of amenity.

RELIANCE LOSS

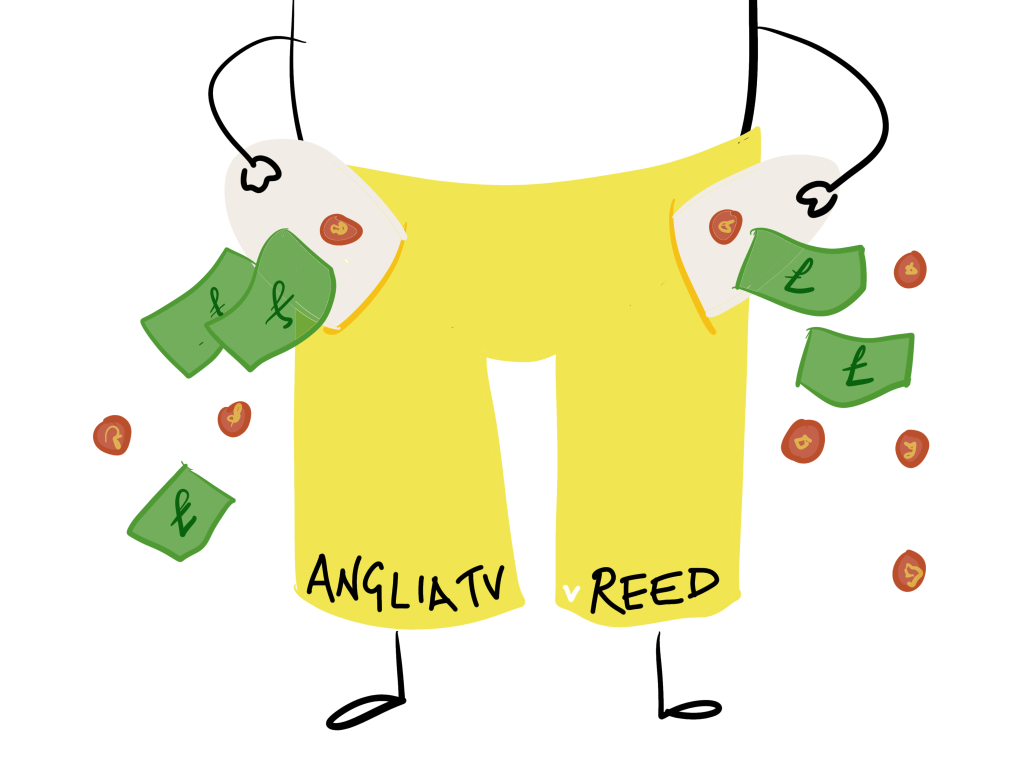

If claims are too speculative the court will assess damages on a reliance loss basis (also known as wasted expenditure) rather than an expectation loss basis. This covers the expenses that the innocent party has incurred in reliance on the contract. In contrast to most awards for damages the aim is to put the innocent party back in the position that they were in before the contract began rather than to the position they would have been in had the contract been performed. A good illustration of reliance loss is Anglia Television v Reed (1972) (CoA).

Anglia TV entered into a contract with Reed, an actor, to play a leading role in a televised play. However, when Reed pulled out from the contract and Anglia TV was unable to find a replacement they had to abandon the play altogether. As they did not know what, if any, profit their film would make, they could not claim damages on an expectation basis but they were able to claim the expenses that they had incurred for the work that had been done on a reliance loss basis.

In Omak Maritime Ltd v Mamola Challenger Shipping Co (2010) (HC), it was commented that reliance losses are not fundamentally different from expectation losses but are rather a species of expectation losses. This is because reliance losses account for the expenditure which is incurred in expectation that the contract will be performed.

EXPECTATION LOSSES OR RELIANCE LOSSES: CAN YOU HAVE BOTH?

In Anglia Television Ltd v Reed, Lord Denning said: ‘Anglia Television then sued Mr Reed for damages. He did not dispute his liability, but a question arose as to the damages. Anglia Television do not claim their profit. They cannot say what their profit would have been on this contract if Mr Reed had come here and performed it. So, instead of a claim for loss of profits, they claim for the wasted expenditure. They had incurred the director’s fees, the designer’s fees, the stage manager’s and assistant manager’s fees, and so on. It comes in all to £2,750. Anglia Television say that all that money was wasted because Mr Reed did not perform his contract … It seems to me that a plaintiff in such a case as this has an election: he can either claim for loss of profits or for his wasted expenditure. But he must elect between them. He cannot claim both. If he has not suffered any loss of profits – or if he cannot prove what his profits would have been – he can claim in the alternative the expenditure which has been thrown away, that is, wasted, by, reason of the breach.

However, this general right of election is subject to an exception where the claimant seeks to recover his reliance loss in an attempt to escape the consequences of a bad bargain (CCC Films (London) Ltd v Impact Quadrant Films Ltd (1985) (HC)).

In this case the claimant purchased a licence from the defendant to promote three films but the defendant lost the film prints and CCC could not therefore promote them. After their claim for loss of profit failed they claimed for the expenditure they had wasted. The defendant’s argument that the claimants were only trying to avoid a bad bargain failed for lack of evidence. The Court said that it is not enough that the defendant shows that the claimant might have made a loss, he has to prove the bad bargain by clear evidence.

In McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) (HC of Australia) it was held that a claimant may be confined to the recovery of his reliance losses where he cannot prove what his expectation losses would have been.