JUMP TO: TRADE CUSTOM: British Crane Hire v Ipswich Plant Hire | Hutton v Warren | Scheps v Fine Art Logistics

PREVIOUS DEALINGS: McCutcheon v David MacBrayne | Henry Kendall Ltd v William Lillico | Hollier v Rambler Motors

TERMS IMPLIED BY LAW: Scally v Southern Health and Social Services Board | Crossley v Faithful & Gould Holdings | Liverpool County Council v Irwin

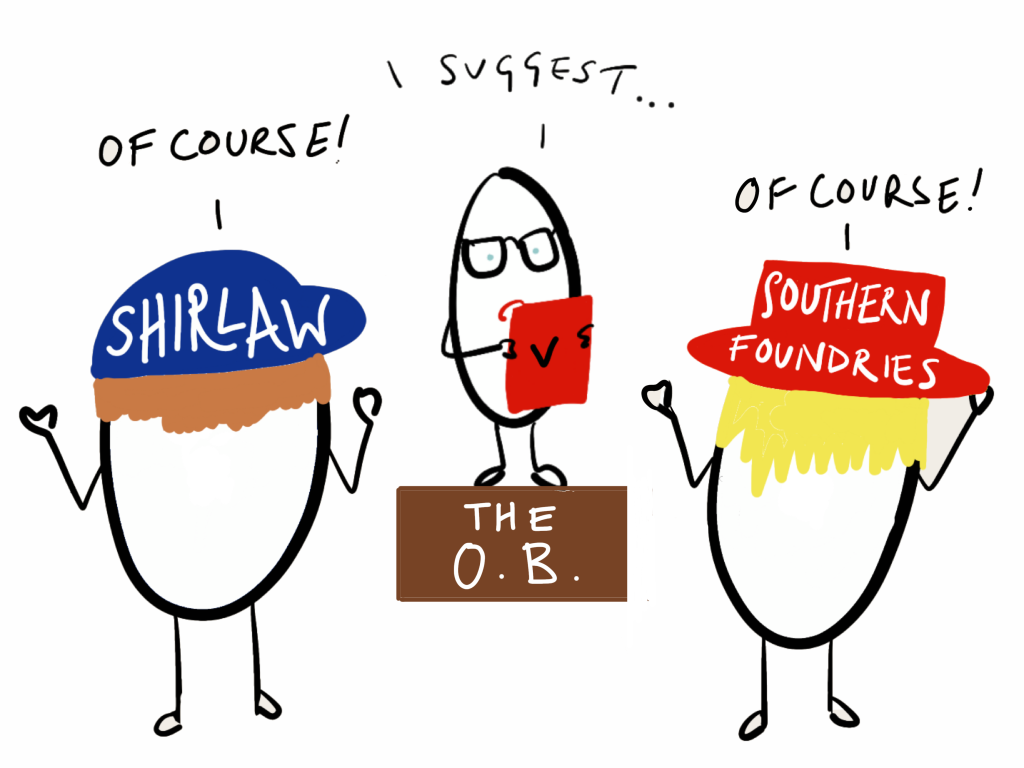

TERMS IMPLIED BY FACT: The Moorcock | Shirlaw v Southern Foundries | Marks and Spencer v BNP Paribas

REVISE | TEST

IMPLIED TERMS

All contracts have terms, these are the elements of the contract that set out what each party expects of the other. Terms are either express or implied. Express terms are those specifically agreed between the parties; I will promise to pay you £50 for which you promise to give me a pair of shoes, these are two express terms of the contract. Implied terms are not specifically agreed by the parties but can be implied.

Here we will be looking at Implication by: Trade Custom, Previous Course of Dealing and Common Law (by Law and by Fact). For Implication by Statute click here.

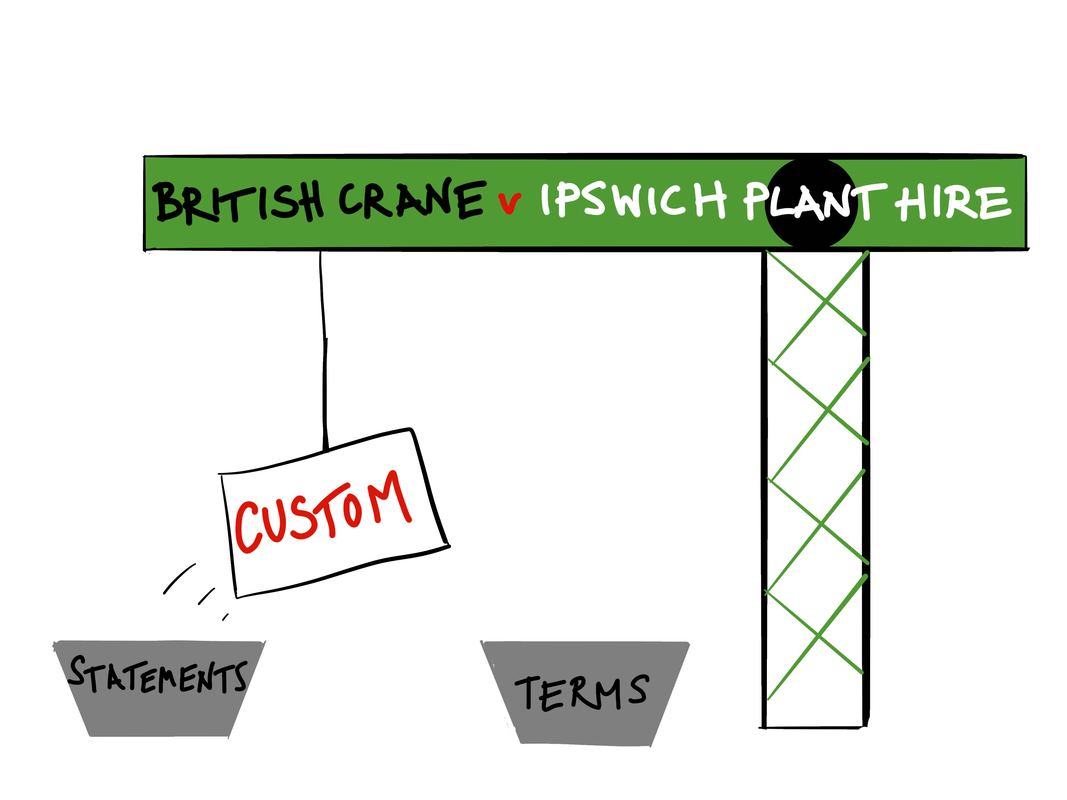

TRADE CUSTOM

In limited circumstances the courts will imply a term based on the custom, or common knowledge, of the industry (British Crane Hire v Ipswich Plant Hire (1975) (CoA)).

In this case the courts implied terms into a contract, even though they had not been specifically stated at the time, because the terms were so standard within the plant hire industry as to be customary.

A contract may also incorporate a relevant custom of a particular market, trade or locality in which the contract is made. In Hutton v Warren (1836) (HC) the court found that it was customary for outgoing tenant farmers to be paid by the landowner for tilling, sowing, and cultivating the land to keep it in good order while the lease expired. As such, Hutton was entitled to claim for reasonable expenses for his labour and efforts bestowed on the land even though Warren had not previously agreed that he would pay for such costs. It was customary that the landowner would pay such costs and therefore such an obligation was implied into the agreement.

This rule will only apply to two parties who work in the same industry and are of equal bargaining power (Scheps v Fine Art Logistics (2007) (HC)).

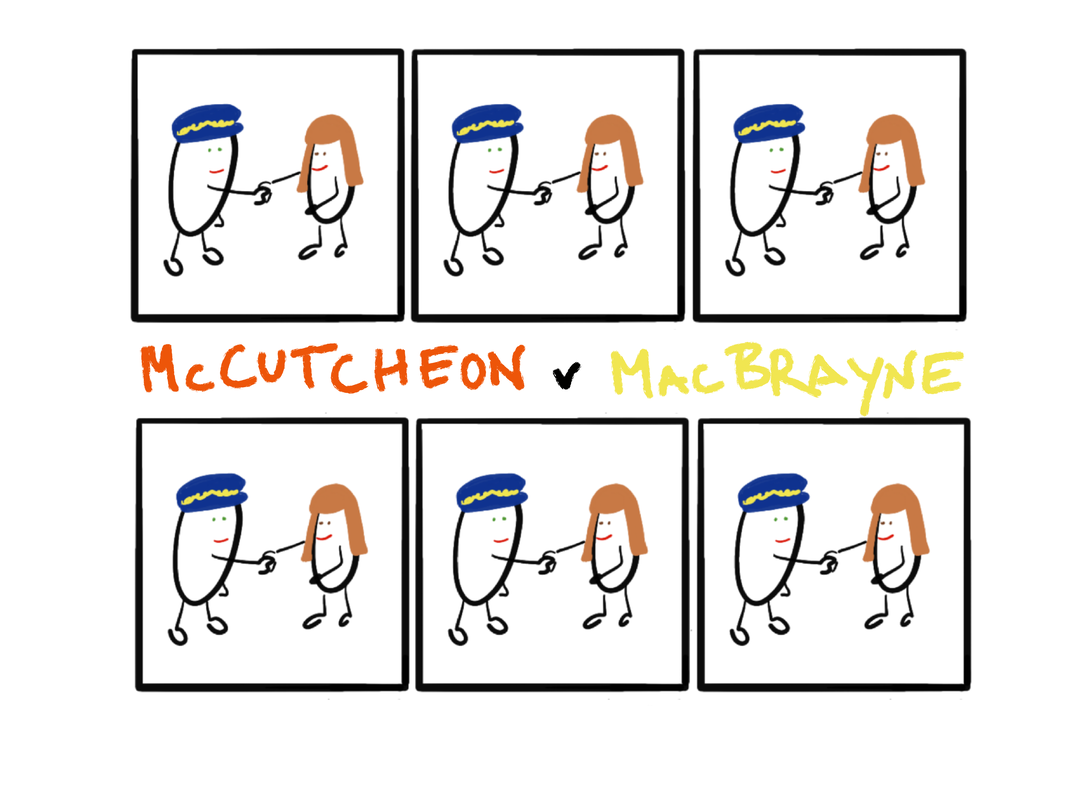

PREVIOUS DEALINGS

If the parties have had regular and consistent dealings then the courts may imply a term from a previous contract (McCutcheon v David MacBrayne (1964) (HoL)).

McCutcheon had used MacBrayne’s ferry service on a number of occasions. On some of those journeys he had signed a slip that included a clause exempting liability for loss. On one trip, for which no slip had been signed, the ferry sank and the claimant’s car was lost. MacBrayne was unable to rely on the exemption clause because the signing of the slip had not previously been consistent enough to constitute a previous course of dealing.

In Henry Kendall Ltd v William Lillico Ltd (1969) (HoL) the House of Lords held that over 100 similar contracts over a period of three years constituted a course of dealing. In contrast, Hollier v Rambler Motors (1972) (CoA) held that 3-4 contracts in five years between a consumer and a garage were not a course of dealing between a consumer and a garage as there was no equal bargaining power and there were too few contracts to establish as much. This case also evidences that the courts are much more likely to imply a term into a B2B rather than a B2C contract.

Also see J Spurling v Bradshaw (1956) (CoA) in which an exemption clause could be incorporated through a course of dealing because every other transaction between the two parties had included the same clause.

TERMS IMPLIED BY COMMON LAW

At common law, there are two types of implied terms: Terms implied by Law and Terms implied by Fact.

Terms ‘implied in law’ are implied into all contracts of a particular type by virtue of the nature of the relationship between the parties. This includes leases, employment, government contracts or any definable category of contractual relationship. Terms are implied by fact to give effect to what the court perceives to be the unexpressed intentions of the parties.

‘…there are two types of implied terms in contracts. The first, is a term which is implied into a specific contract based on the express terms, commercial common sense, and the facts known to both parties at the time the contract was concluded (implied by fact). The second type of implied term can arise, unless expressly excluded, by law which imposes certain terms in certain types of agreements – either through statute or the common law.’

Lady Hale in Geys v Société Générale (2013) (SC)

TERMS IMPLIED BY LAW

In Scally v Southern Health and Social Services Board (1992) (HoL), Scally and other doctors working for HSSB were not eligible for pension benefits because they had not been in paid employment for 40 years before they retired. However, HSSB had failed to notify them that they could buy extra pension years. Scally and the doctors argued that this was a breach of an implied term in their contract of employment

The House of Lords held that the employers had breached a contractual duty, implied into the employment contracts, to properly inform their employees about their rights. Lord Bridge said that the test for implication by law is not quite business efficacy but a ‘search, based on wider considerations, for a term which the law will imply as a necessary incident of a definable category of contractual relationship.’

In Crossley v Faithful & Gould Holdings Ltd (2004) (CoA), it was held that there is no implied term in employment contracts that an employer will take “reasonable care for the economic well-being of his employee”.

Another important case illustrating terms implied by law is Liverpool County Council v Irwin (1977) (HoL). The Irwins were council tenants of a flat in a high rise building owned by Liverpool City Council (LCC). They withheld payment of their rent in protest because they said that the LCC was not keeping the common parts of the building in good repair and the conditions were not satisfactory. The conditions included defective lifts, unlit staircases and an overflowing water cistern. LCC sought to evict the Irwins and take possession of the flat but the Irwins counterclaimed for breach of duty to maintain the common parts of the building. The court did not look at the parties’ intentions but at the type of contract: Landlord and Tenant. The court found that there is an implied term in tenancy agreements for a landlord to be responsible for and maintain the common areas because it was a standardised contractual relationship. However, it was found that the LCC had not breached this duty because they had taken reasonable steps to maintain the common parts and it was due to continuous vandalism that the common parts of the building were in poor condition. This was said to be outside of the LCC’s control.

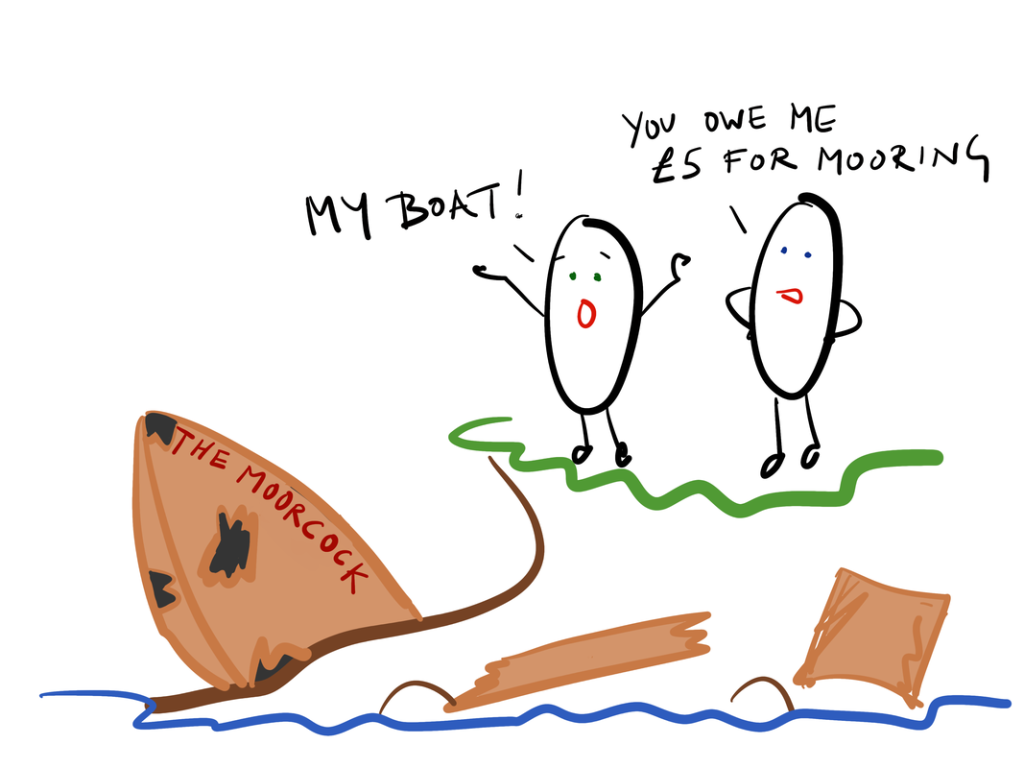

TERMS IMPLIED BY FACT

Sometimes the courts will imply a term in order to make the contract work, or be business efficient. Two different tests have been developed by the courts; the Business Efficacy Test and the Officious Bystander Test.

|

|

BUSINESS EFFICACY TEST

If a term is absolutely necessary to make a contract business efficient (not just reasonable) then the courts may imply it into the contract.

In The Moorcock (1889) (CoA) the claimant contracted to moor his boat at the defendant’s wharf on the Thames. Both knew that the tide would go out, when it did the boat hit hard ground rather than mud and was damaged. The claimant argued that there was an implied term of reasonable care without which the contract would not work or have no business efficacy. The court agreed.

|

OFFICIOUS BYSTANDER TEST

If a term is so obvious that if it were suggested by an officious bystander both parties would say ‘Oh, of course!’ then it may be implied by the court.

In Shirlaw v Southern Foundries Ltd (1926) (CoA) the claimant was employed as Managing Director of Southern Foundries for a term of 10 years. When the company was taken over the new owners dismissed Shirlaw as a Director. He took them to court for wrongful dismissal on the basis that he could not be Managing Director without also being a Director. The court agreed and implied a term into his Managing Director’s contract that he must also be a Director.

|

Despite the law in this area having experienced significant developments (see BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Hastings Shire Council (1977) and Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom (2009) (PC Belize)) in Marks and Spencer v BNP Paribas (2015) (SC) the Supreme Court reasserted the use of the two original tests outlined above.

In Lord Neuberger’s words the test remains whether a term ‘is necessary for business efficacy or that it is so obvious that it went without saying’, being reasonable and equitable is not enough. Lord Neuberger explicitly rejected Lord Hoffmann’s approach from Belize and stated that interpretation of the contract is not the same as the implication of terms.

More recent cases of Trump International Golf Club Scotland Limited v The Scottish Ministers (2015) (SC) and Ali v Petroleum Company of Trinidad and Tobago (2017) (PC of Trinidad & Tobago) have affirmed Lord Neuberger’s assertion of the original tests. The tests remain the officious bystander and business efficacy tests.

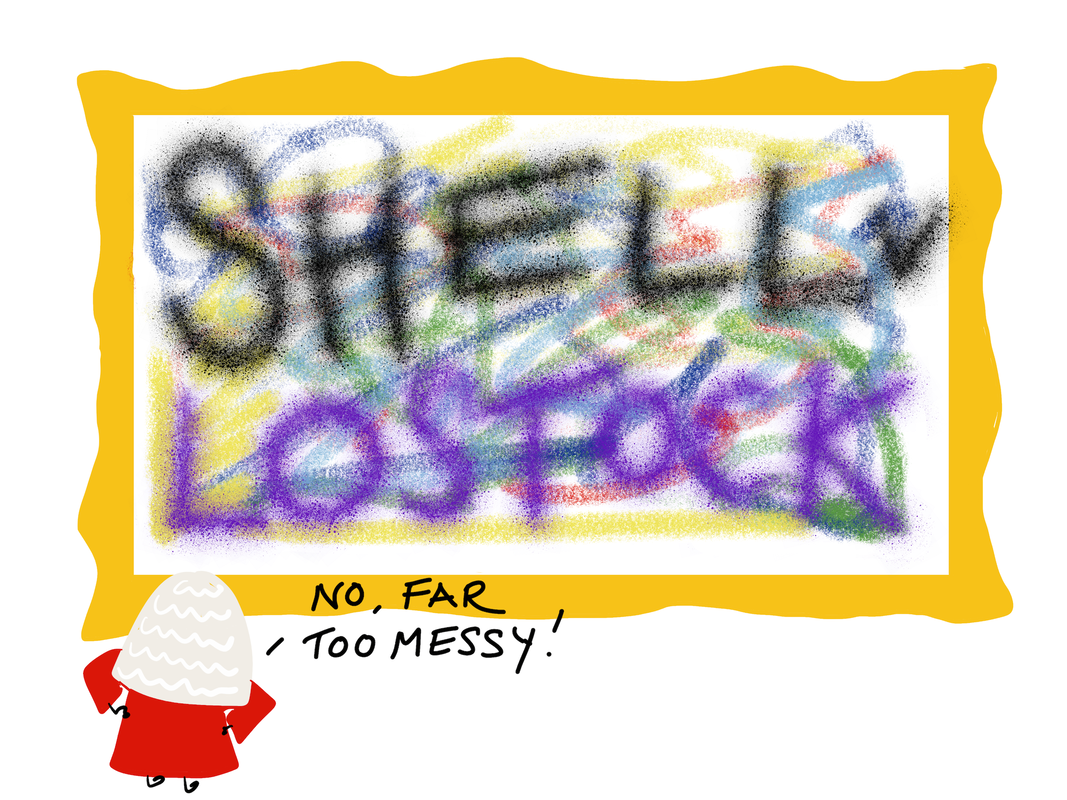

SUFFICIENT PRECISION

In order to be implied into a contract a term must ‘be formulated with sufficient precision’ (Shell UK v Lostock Garage (1976) (CoA)).

In this case Lostock wanted the courts to imply a term into his contract with Shell that they should not ‘abnormally discriminate’ against Lostock in favour of competing garages. The court refused for several reasons. The term lacked certainty and was not precise enough, Shell would probably never have agreed to this term at the time of contracting (therefore it would not reflect the intentions of the parties) and although equitable it was not necessary for business efficacy.