JUMP TO: COMMON MISTAKE – EXISTENCE – Couturier v Hastie | Strickland v Turner | McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission – OWNERSHIP – Cooper v Phibbs – QUALITY – Leaf v International Galleries | Great Peace Shipping v Tsavliris Salvage – MUTUAL MISTAKE – Raffles v Wichelhaus | Smith v Hughes – UNILATERAL MISTAKE – Hartog v Colin & Shields | Chwee Kin Keong v Digilandmall.com | Smith v Hughes | Cundy v Lindsay | Shogun Finance v Hudson | King’s Norton Metal Co v Edridge, Merrett & Co | Phillips v Brooks | Ingram v Little | Lewis v Averay | Saunders v Anglia Building Society | Trustees of Beardsley Theobalds Retirement Benefit Scheme v Yardley

REVISE | TEST

MISTAKE

A mistake is a misunderstanding or erroneous belief about something so fundamental to the contract that when discovered makes the contract impossible to perform. The operative, or fundamental, mistake ‘renders the subject matter of the contract essentially and radically different from the subject matter which the parties believed to exist’, Steyn J, Associated Japanese Bank v Credit du Nord (1988) (HC).

A mistake renders the contract void ab initio (from the beginning), as if there has been no contract, so the parties have no rights or obligations to enforce.

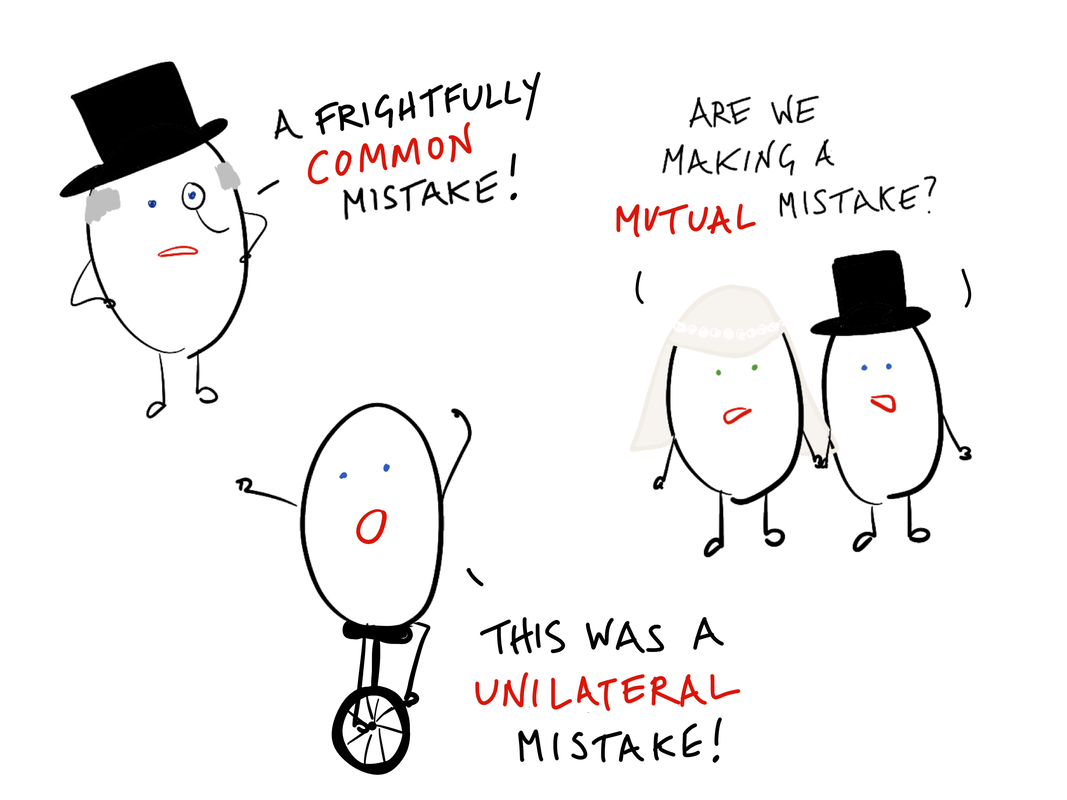

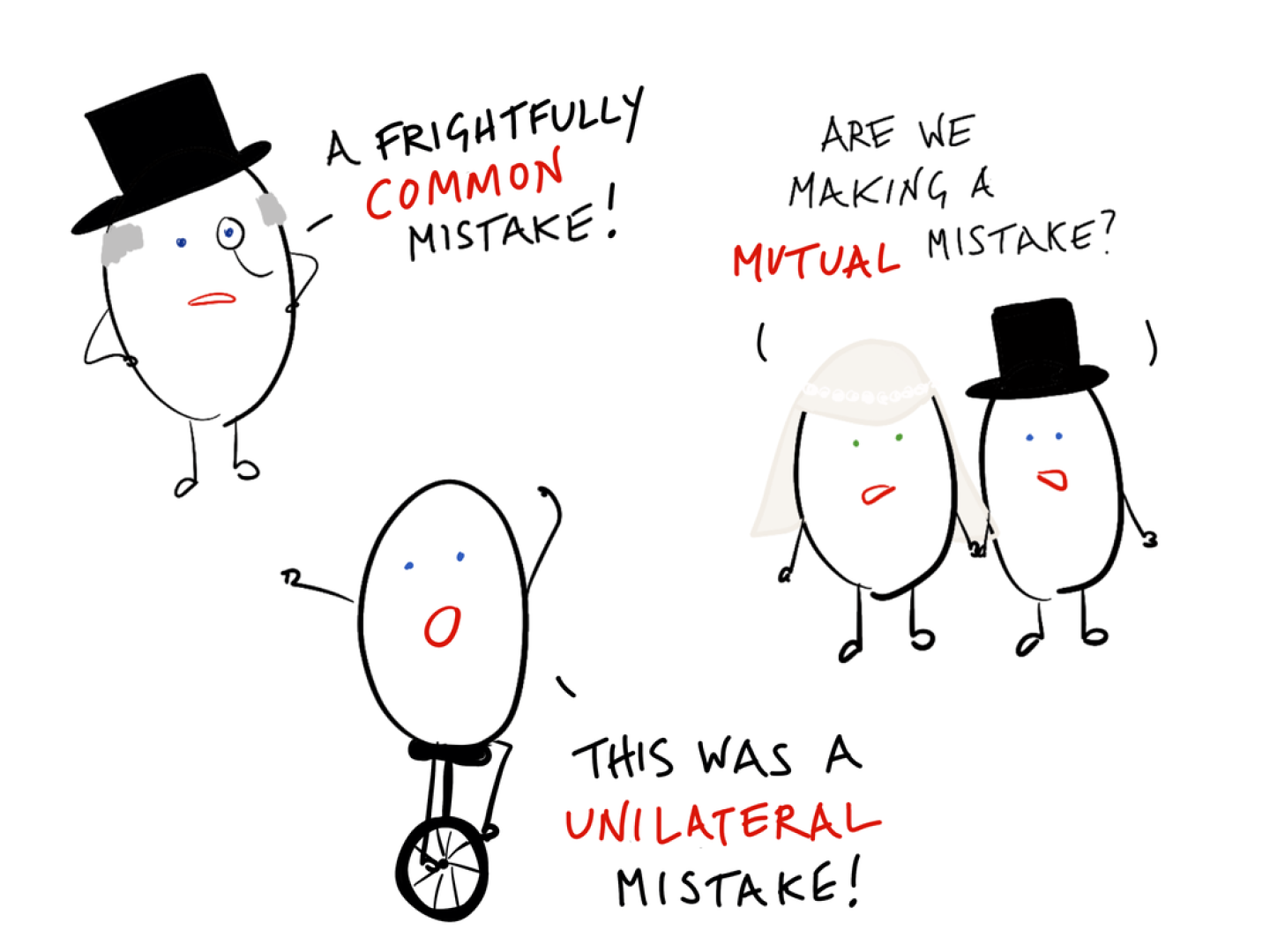

There are three types of mistake;

COMMON MISTAKE

A common mistake is one believed by both parties at the time of entering into the agreement.

There are three different categories of common mistake;

EXISTENCE OF SUBJECT MATTER

|

OWNERSHIP OF SUBJECT MATTER

|

QUALITY OF SUBJECT MATTER

|

EXISTENCE OF SUBJECT MATTER

This happens when both parties are mistaken as to the existence of the subject matter of the contract, it is also known as res extincta. An example of this is Couturier v Hastie (1856) (Court of Common Pleas).

A cargo of corn was sold by Couturier to Hastie whilst it was in transit to England. However, unknown to either of them, the cargo had degraded on the way and the ship’s captain had sold it before the contract was made. Couturier sought to enforce payment for the goods on the grounds that Hastie had attained title to the goods and therefore bore the risk of the goods being damaged, lost or stolen. The court held that the contract was void ab initio because the subject matter of the contract did not exist at the time the contract was made.

Another example of this is Strickland v Turner (1852) (Court of Exchequer). Strickland contracted with an insurance company for an annuity on Turner’s life. In fact Turner was dead when the contract was made. This was found to be a common mistake and the contract was void. Also see Galloway v Galloway (1914) in which a divorce settlement was void because the couple had not in fact been married as the husband’s previous wife was still alive.

IS THE MISTAKE COMMON BETWEEN THE PARTIES?

There will be no common mistake if one party relied upon the greater knowledge of the other party for their information about the existence of the subject matter. The party with greater knowledge has therefore assumed the risk for its existence. In McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) (HC of Australia) McRae obtained a tender from the Commonwealth Disposals Commission (CDC) to rescue an oil tanker that was located on the Jouramound Reef. However, after reaching the location McRae discovered that there was no oil tanker. They sued the CDC for breach of contract. CDC argued that there had been a common mistake and therefore there was no contract and no breach. However, the Court of Appeal found that because the CDC had promised that the wreck existed (even though they had only heard rumours of its existence) they were responsible for the risk that it did not exist and there was no common mistake.

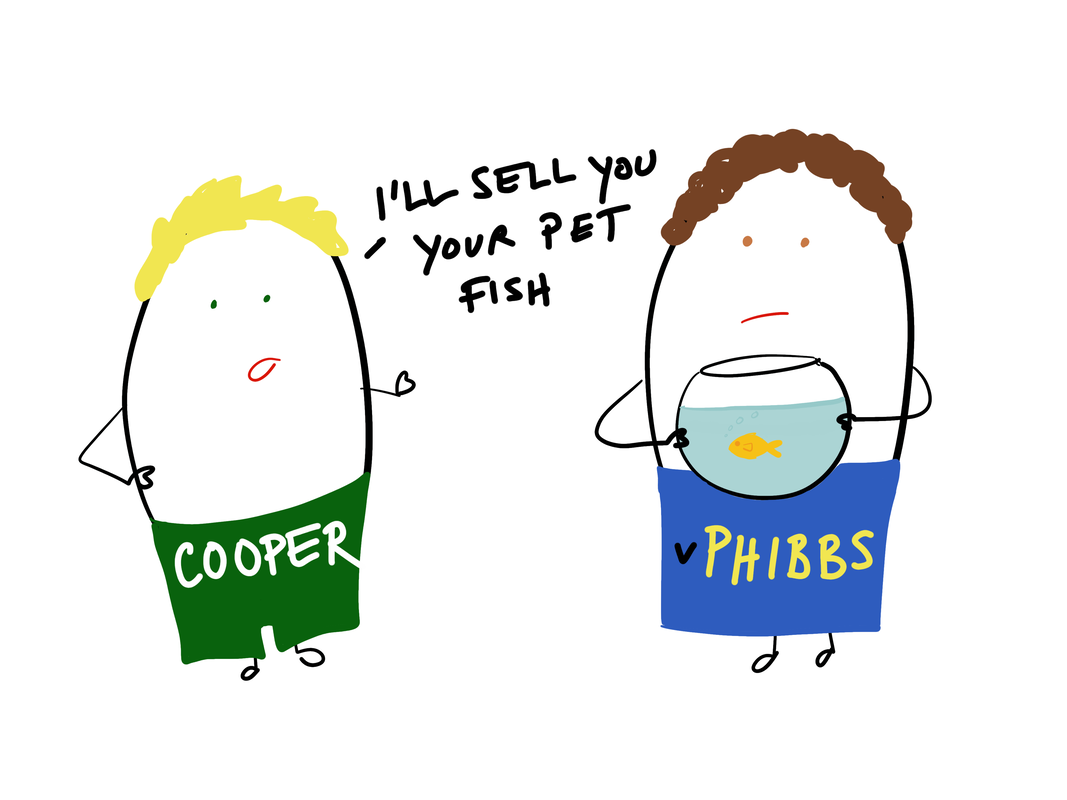

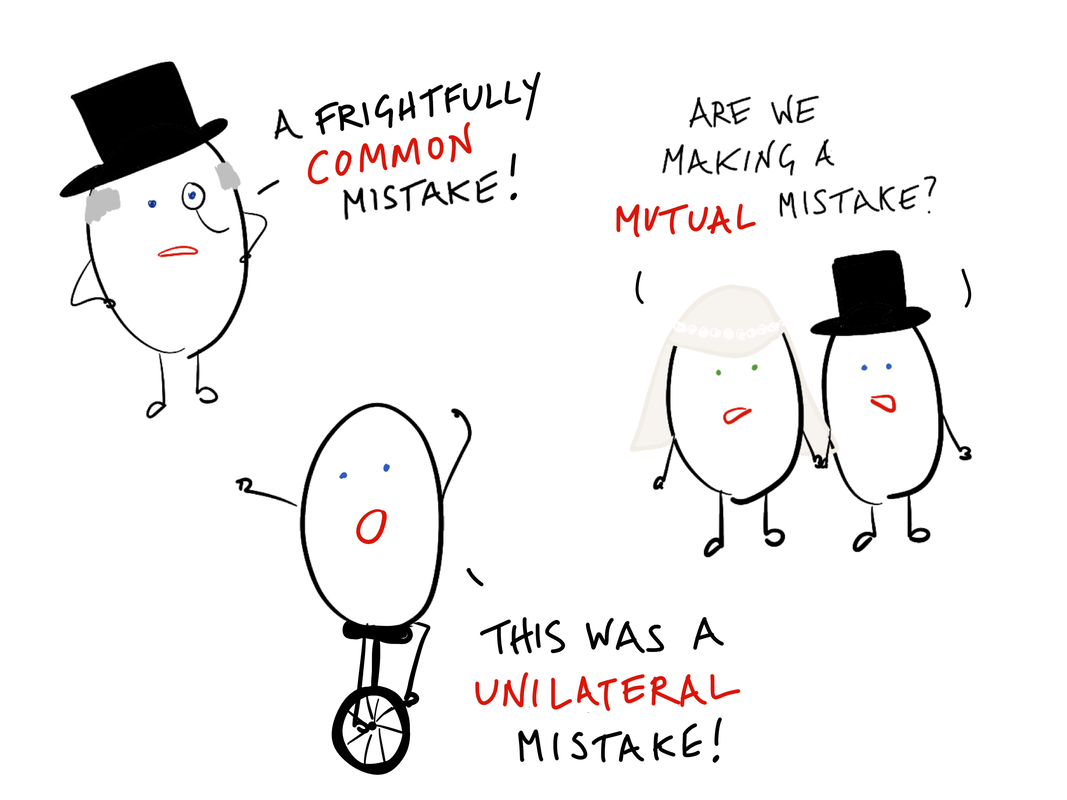

OWNERSHIP OF SUBJECT MATTER

This is when a mistake is made as to ownership and the goods being contracted for actually already belong to the purchaser. This is also known as res sua (Cooper v Phibbs (1867) (HoL)).

Cooper leased a fishery from his uncle. When the lease came up for renewal his uncle had died and the property belonged to Phipps, the uncle’s wife, who renewed the nephew’s lease. However, it later became known that the uncle had given his nephew a life tenancy to the fishery in his will. The renewed lease was held to be voidable for mistake as to ownership because the nephew already had a beneficial ownership in the fishery.

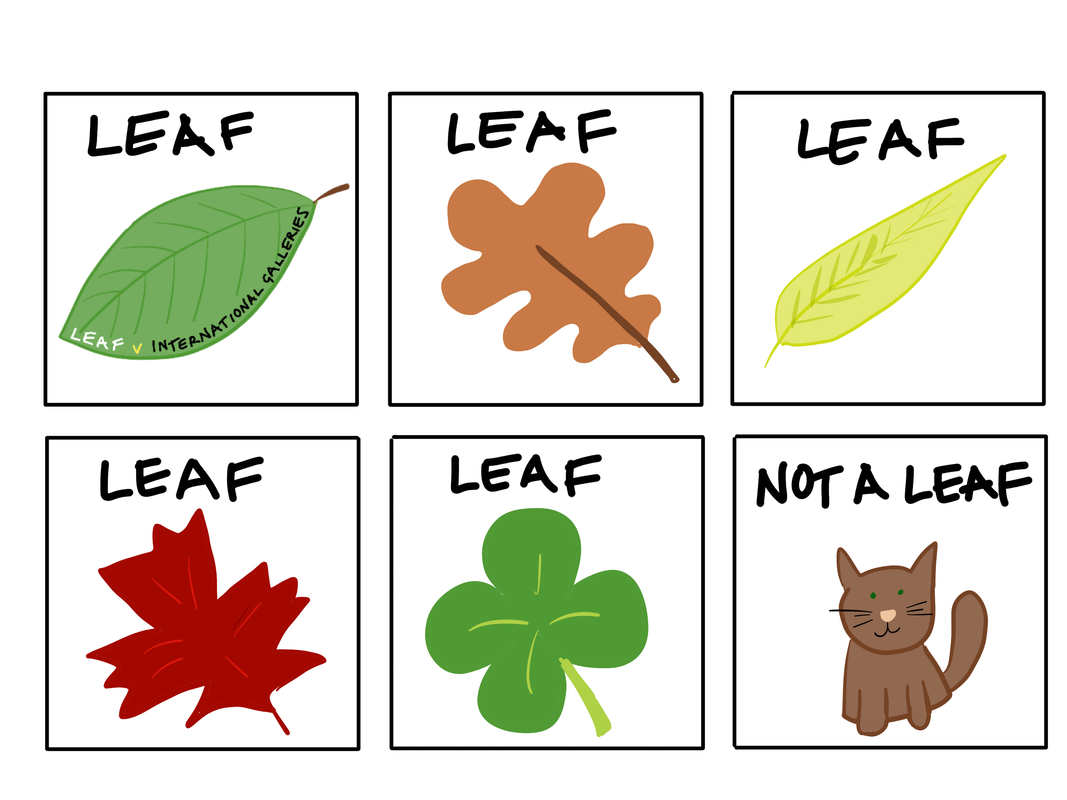

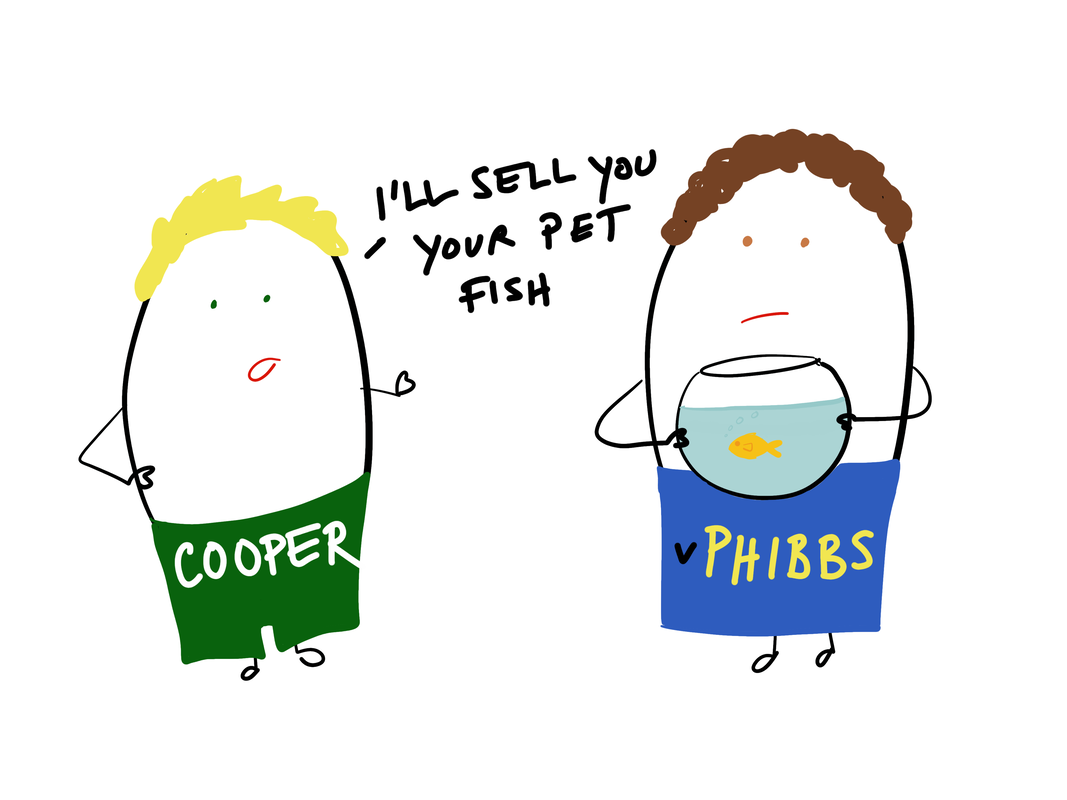

QUALITY OF SUBJECT MATTER

A mistake in regards to quality of the subject matter ‘is the mistake of both parties, and it is as to the existence of some quality which makes the thing without the quality essentially different from the thing as it was believed to be’, Lord Atkin, Bell v Lever Bro (1932) (HoL). It is not the same as satisfactory quality as defined by the Sale of Goods Act 1979.

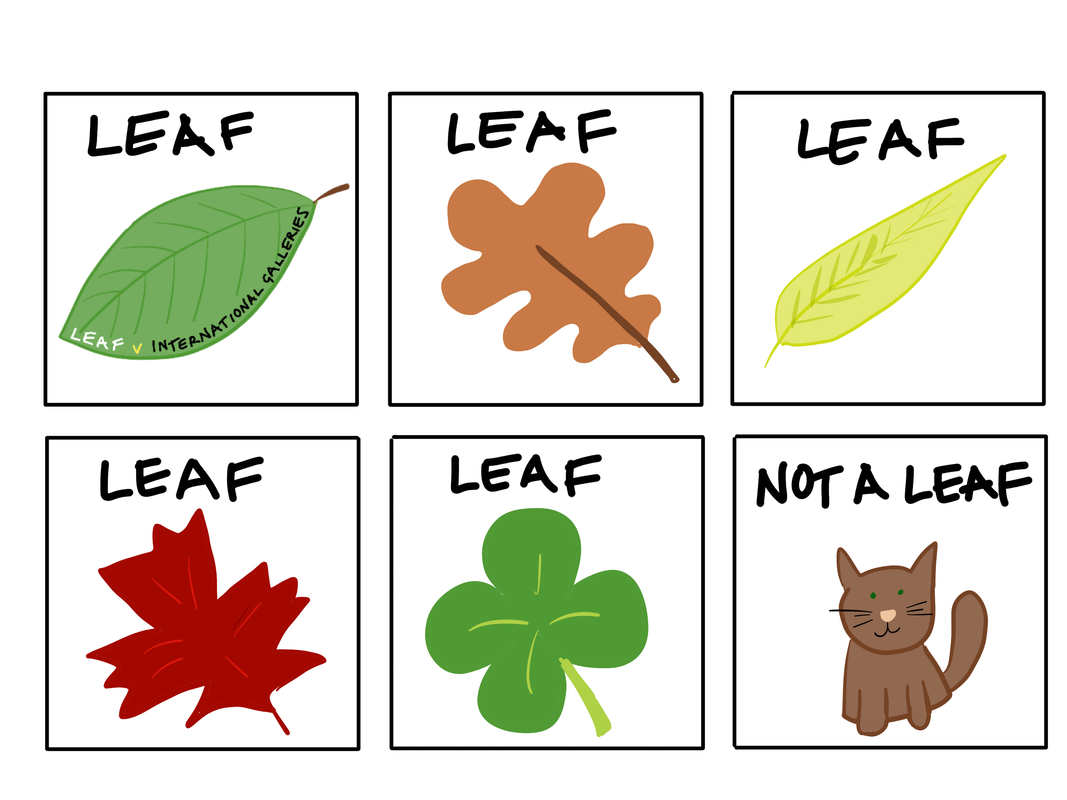

A good example of this is Leaf v International Galleries (1950) (CoA).

Leaf purchased a painting from International Galleries which both parties believed to be by John Constable (a famous landscape painter). However, five years later it was discovered that the painting wasn’t by Constable. Leaf brought an action against the gallery on the grounds of misrepresentation but the issue of mistake was raised in obiter dicta. The mistake did not render the quality of the subject matter essentially different from what it was believed to have been by both parties (i.e. a painting of Salisbury Cathedral). If it had turned out to be a photograph and not a painting this would have been a mistake as to quality.

In most cases a mistake as to the quality of the subject matter will not be fundamental enough to make the contract void and redress may be available for breach of contract instead. The narrow limits of the doctrine were confirmed in Great Peace Shipping v Tsavliris Salvage (2002) (CoA). Tsavliris had contracted to hire the ship Great Peace to salvage another boat which he was told was only 35 miles away. In fact it was 410 miles away. However, because it could still arrive in time to perform the contract the mistake was not fundamental enough and did not render performance impossible.

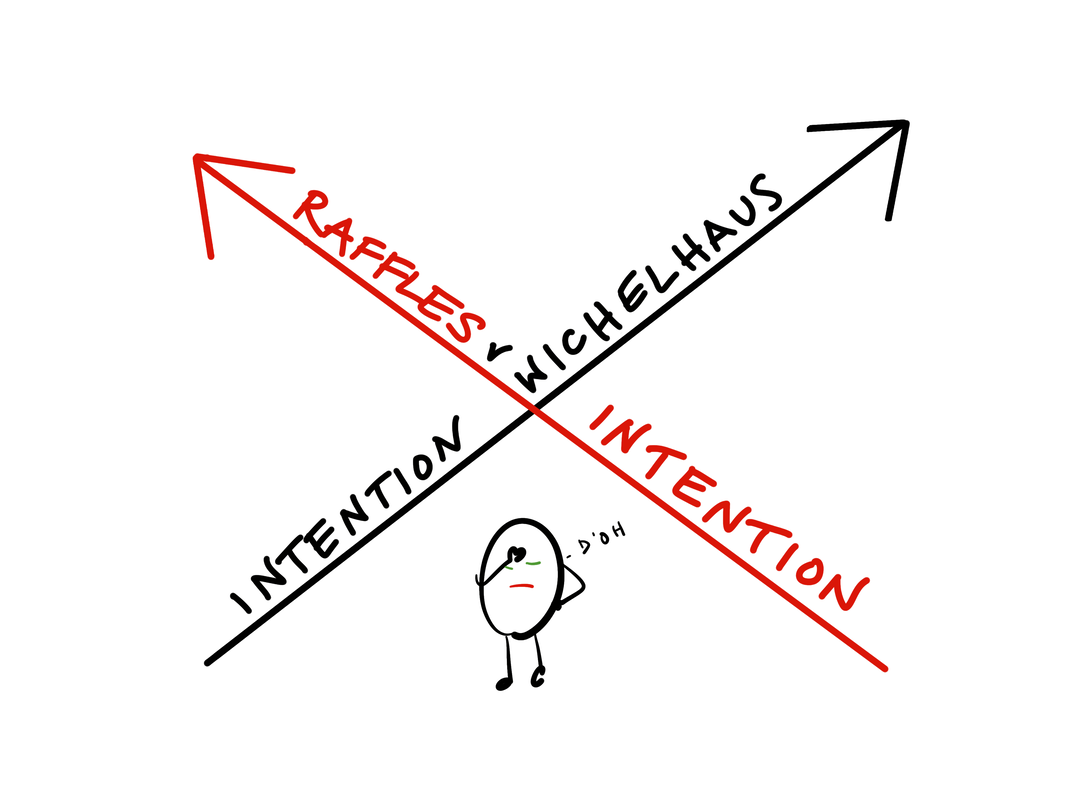

MUTUAL MISTAKE

A mutual mistake is one whereby both parties have misunderstood each others’ intentions. There is no consensus ad idem, or common intention, between the parties and therefore there can be no agreement and no contract (Raffles v Wichelhaus (1864) (HC)).

Raffles and Wichelhaus entered into a contract for the sale of cotton. This would be shipped from the port of Bombay on board a vessel known as The Peerless. In fact there were two ships named The Peerless, one which sailed in October and the other which sailed in December. Raffles thought that the relevant sailing date was December, whereas Wichelhaus thought it was October. In applying the objective test to establish a common intention between the parties the court held that the contract was void as there was no consensus ad idem.

If the court is able to establish a common intention between the parties then there is agreement and can be no common mistake.

What is the common intention? When trying to establish what was the common intention between the parties at the time of contracting the court will ask what a reasonable person viewing the interactions between the parties would understand as the shared meaning of the contract (Smith v Hughes (1871) (HC)). Mr Hughes was a race horse owner who specifically needed old oats to feed his horses. Hughes bought oats from Smith having seen a sample of new oats, when they were delivered he refused to pay. The court had to ask, would the reasonable man, witnessing the parties have understood the contract to be for old oats or new oats. They held that although Hughes had needed old oats, he had seen a sample of new oats and had not communicated to Smith his need for old oats, therefore the common intention of the parties was for new oats.

UNILATERAL MISTAKE

A unilateral mistake is when ONE party to the contract is mistaken and the other party is aware, or deemed to have been aware, that a mistake has been made.

MISTAKE AS TO A TERM

If a mistake has been made by one party regarding a fundamental term of the contract (not a collateral matter) and the other party is aware of that mistake the courts will not allow that party to take advantage of the other’s mistake (Hartog v Colin & Shields (1939) (HC)).

Colin & Shields mistakenly offered to sell Hartog fur pelts at a price per pound instead of a price per piece, making it much cheaper than normal. The court held that the contract was void for mistake. Even if the claimant had not realised the mistake they should have realised because fur was always sold per piece and not per pound and therefore they could not take advantage of the defendant’s mistake. The court said that one cannot ‘snap up’ an offer when the real intention of the other party is known.

Also consider the more modern case of Chwee Kin Keong v Digilandmall.com (2006) (HC Singapore). The defendant company advertised printers on their website for $66 rather than the retail price of around $3,400. The claimant bought 100 printers. The court held that the price was so absurdly low that it could only have been a mistake and not the intention of the party, therefore the claimant’s and defendant’s intentions were not the same and there could not be a contract.

TERM NOT COLLATERAL MATTER

The mistake must be regarding a term of the contract and not a collateral matter otherwise there will have been offer and acceptance upon the same terms (Smith v Hughes (1871) (HC)).

Smith purchased oats from Hughes based on a sample that he had been shown. He believed that he would be sold old oats which he could use to feed his horses. However, fresh new oats were delivered and Smith brought an action against the defendant on the grounds of mistake. It failed as the courts held that the mistake was not in relation to a fundamental term of the contract (they were still oats) but instead a collateral matter (the quality of the oats as old or new).

MISTAKE AS TO IDENTITY

Mistake as to the identity of the other party generally involves one party (the rogue) fraudulently pretending to be someone that they’re not in order to persuade the other party to contract with them.

For a claim to be successful the court must be persuaded that the specific false identity of the rogue was crucial to the other party’s decision to enter into the contract. If they would have contracted anyway, regardless of the other party’s identity, then the mistake was not fundamental to the contract.

Claims are divided into those where the parties contracted at a distance and those where they contracted face-to-face. The case of Shogun Finance v Hudson (2003) (HoL) affirmed this distinction although the decision was heavily disputed by the minority.

INTER ABSENTES – NOT PHYSICALLY PRESENT

If the parties contracted at a distance and never physically met then the courts will only find mistake if the claimant can prove that they intended to contract with a legitimate person whom the rogue was pretending to be. In other words, it was important to the claimant with whom they were contracting and in this respect they had been deceived (Cundy v Lindsay (1878) (HoL)).

A rogue buyer ordered goods from Lindsay and provided his address as Blenkarn & Co, 37 Wood Street, Cheapside. However, the order form was signed as Blenkiron & Co. Lindsay knew of the reputable Blenkiron & Sons which was based at 123 Wood Street, Cheapside. Believing that the order was from Blenkiron & Sons and without checking the address, Lindsay dispatched the goods to 37 Wood Street, the address provided by the rogue. Blenkarn subsequently sold some of the goods to Cundy who purchased in good faith before the fraud was discovered. It was held that the contract was void on the grounds of unilateral mistake because Cundy believed that they were contracting with Blenkiron and therefore title to the goods never passed from Lindsay to the rogue.

In Shogun Finance v Hudson (2003) (HoL) a rogue purchased a car on hire purchase from a car dealer. He used a false driving licence which the car dealer communicated to Shogun Finance (the finance company). They performed a credit search on the fake ID and gave the go-ahead for the sale. The rogue then sold the car to Hudson. When Shogun Finance realised the deception they tried to reclaim the car from Hudson, arguing that the contract was void for mistake. The court held that because Shogun Finance and the rogue had not met face-to-face and because the presumed identity of the rogue was crucial to the contract (i.e. without the specific credit check they would not have sold him the car) there had been an inter absentes unilateral mistake. The contract was therefore void and Hudson did not own the car. The dissenting judges were highly critical of the judgment, believing that there should be no distinction between face-to-face and at a distance contracts.

For there to be a valid mistake as to identity there must be two entities that have been mistaken for each other, not one fake entity (King’s Norton Metal Co v Edridge, Merrett & Co (1897) (CoA)). King’s Norton supplied goods to a fake company called Hallam & Co after receiving an order by letter on headed paper. When they realised that the company did not exist they brought a claim for mistake. However, it was not successful because there was no mistake as to identity, they had always intended to contract with Hallam & Co rather than any other entity.

INTER PRAESENTES – DEALING FACE-TO-FACE

If the parties are face-to-face when they contract there is a presumption that the mistaken party intends to deal with the person who is physically present. If the buyer lies about their identity this must be proved to have been vital to the contract otherwise it will not be a mistake that can render the contract void (Phillips v Brooks (1919) (HC)).

A rogue buyer purchased a few items of jewellery, including a ring for his wife, from Phillips after presenting himself as Sir George Bullogh. Phillips accepted the cheque given as payment for the ring after having verified the address provided by the rogue with the address of Sir George Bullogh in a directory. The rogue pawned the ring with the defendant pawn broker, Brooks, before the fraud came to light. The claimant brought an action against the defendant on the grounds of unilateral mistake as to identity. The court held that the contract was not void for mistake and that where parties deal face-to-face there is a presumption that the parties intended to deal with the person in front of them and no other. The claimant was unable to show that they would only have sold the ring to Sir George Bullogh.

REBUTTING THE PRESUMPTION

This presumption can be rebutted if the mistaken party can prove that the false identity of the rogue was crucial to their willingness to contract. This was upheld in the highly criticised but never overruled case of Ingram v Little (1961) (CoA).

Two sisters sold their car to a rogue. They wanted a cash payment but the rogue, impersonating a wealthy business man, offered to pay by cheque. The sisters checked the rogue’s fake credentials at the post office and decided to accept the cheque. Despite the case being very similar to Phillips v Brooks the court found that there had been a mistake as to identity as the sisters would only have contracted with the wealthy business man.

One of the judges, Pearce LJ, distinguished this case from Phillips v Brooks based on the timing and purpose of the deception. In Phillips v Brooks the fake name was given after the deal was concluded, its purpose being to allow the rogue to leave with the goods before the cheque cleared, not to induce the seller into the contract.

The presumption as set out in Phillips v Brooks was followed in Lewis v Averay (1972) (HC). Lewis sold his car to a rogue who pretended to be Richard Greene (a well known actor). When Lewis asked for ID he presented a Pinewood Studios pass. The court held that as a face-to-face interaction Lewis had intended to deal with the rogue and therefore the contract was not void. The decision in Ingram v Little was criticised by all of the judges.

If a party whose property has been bought and sold on by a rouge can prove mistake then the contract is void and the onward sale of their property to an innocent third party is also void as the rogue never had legal title and their property. If the original party can only prove misrepresentation, making the contract voidable but not void, then the title will have passed to the rogue, and subsequently the innocent third party, leaving the original party unable to reclaim their property.

MISTAKE AS TO SIGNED DOCUMENTS

If it can be shown that the party signing a document was fundamentally mistaken as to the nature of the document then the contract can be void for mistake. Non est factum means ‘it is not my deed’.

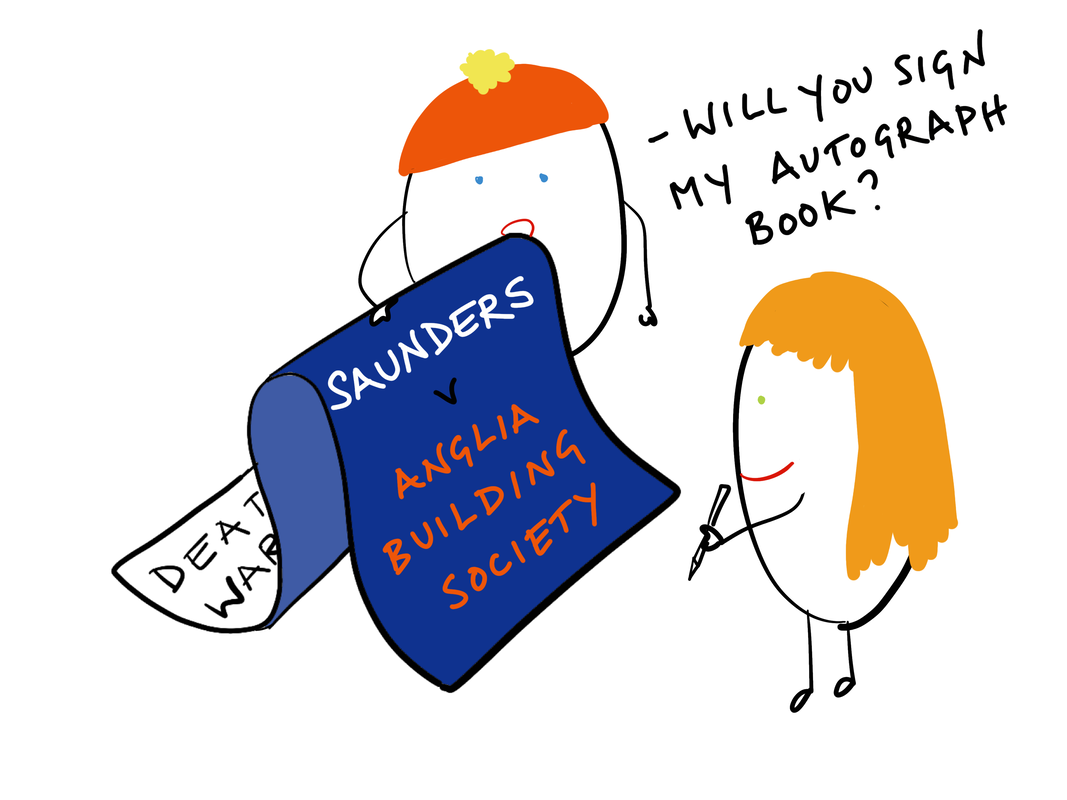

In order to successfully plea non est factum the signer must not have been careless in signing and there must be a radical difference between the document that was signed and what the signer thought she was signing (Saunders v Anglia Building Society (1971) (HoL)).

A 78 year old woman signed documents believing that they assigned the legal rights in her property to her nephew with the right to remain in the property rent free for life. As she could not find her reading glasses she signed the document on the assurances made by her nephew and his friend. In fact, she had signed a document giving the nephew’s friend the right to raise a mortgage on the property in favour of Anglia Building Society. When he defaulted on the loan and the bank sought possession of the property she raised the plea of non est factum. The House of Lords rejected the plea on the grounds that the document she had signed was not substantially different from what she had expected as it assigned the right in her property to someone, just the wrong person and she was capable of checking the document before signing.

The courts are unwilling to allow this plea very often as parties who sign documents should take care that they know what they are signing. The recent case of Trustees of Beardsley Theobalds Retirement Benefit Scheme v Yardley (2011) (HC) is a rare example where a court found that a signed guarantee was not enforceable. In this case the signor was falsely led to believe that he was only witnessing a signature rather than signing the document. The court also found that the signature was obtained by undue influence.