JUMP TO: Nature Resorts Ltd v First Citizens Bank – ACTUAL UNDUE INFLUENCE – Morley v Loughnan | UCB Corporate Services v Williams – PRESUMED UNDUE INFLUENCE – Allcard v Skinner | Macklin v Dowsett | Hammond v Osborn | Lloyds Bank v Bundy | National Westminster Bank v Morgan | Goldsworthy v Brickell – THIRD PARTY UNDUE INFLUENCE – Barclays Bank v O’Brien | Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) | CIBC Mortgages v Pitt | Niersmans v Pesticcio

REVISE | TEST

UNDUE INFLUENCE

Undue influence is an equitable doctrine. It arises if one party was unduly pressurised by the other party and did not enter freely and independently into the contract. It exists to save parties from being victims of undue pressure rather than to save them from their own folly.

Traditionally, undue influence has been divided into Actual Undue Influence and Presumed Undue Influence. However, Lord Briggs and Lord Burrows note in Nature Resorts Ltd v First Citizens Bank Ltd (2022) (PC) undue influence is ‘a single concept’ and so does not have ‘two different forms’. Instead, ‘the correct analysis of the two categories is that they refer to two different ways of proving undue influence’. Contracts affected by undue influence are voidable not void.

The case law derives from Bank of Credit and Commerce International v Aboody (1989) (CoA) and was approved in Barclays Bank v O’Brien (1994) (HoL). However, the more recent case of Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2002) (HoL), which concerned joint claims from eight wives who said they had been unduly influenced by their husbands to take out mortgages on their properties, has clarified the legal position.

ACTUAL UNDUE INFLUENCE

Actual undue influence occurs when one party exerts improper influence on the other party making them enter into the contract. There is an obvious overlap here with common law duress. In Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2002) (HoL) it was described as ‘overt acts of improper pressure or coercion such as unlawful threats.’

An example of this is Morley v Loughnan (1893) (HC) in which a vulnerable man who had given over £140,000 to the Close Sect of Plymouth Brethren before he died. He was found to have done so because of actual undue influence exerted by a sect leader, Loughnan, who used his position to influence the claimant. Morley, who was sickly, had gone to live with Louhgnan who was completely in control of Morley’s affairs including his diet and medicines. Wright J. stated that there was no need to find a special relationship between the parties because ‘the defendant took possession, so to speak, of the whole life of the deceased, and the gifts were…the effect of that influence and domination.’

The claimant does not have to have suffered any manifest disadvantage from entering into the contract, it is enough that they were pressurised to enter into the contract (CIBC Mortgages v Pitt (1994) (HoL)). In this case a campaign of sustained pressure from the husband on the wife to take out a second mortgage was actual undue pressure. However, the wife’s claim ultimately failed because there was no way that the bank could have known about the pressure placed on the wife. It would be impractical for banks to be put on notice of undue influence arising from all joint agreements with spouses. It does not matter if the claimant would have entered into the contract anyway (UCB Corporate Services v Williams (2002) (CoA)).

PRESUMED UNDUE INFLUENCE

Whereas actual undue influence exists when there has been a positive influence exerted on one party, presumed (or evidential) undue influence happens when one party has allowed a relationship of trust and confidence to influence the other party and has failed to ensure that the contract was entered into freely and independently.

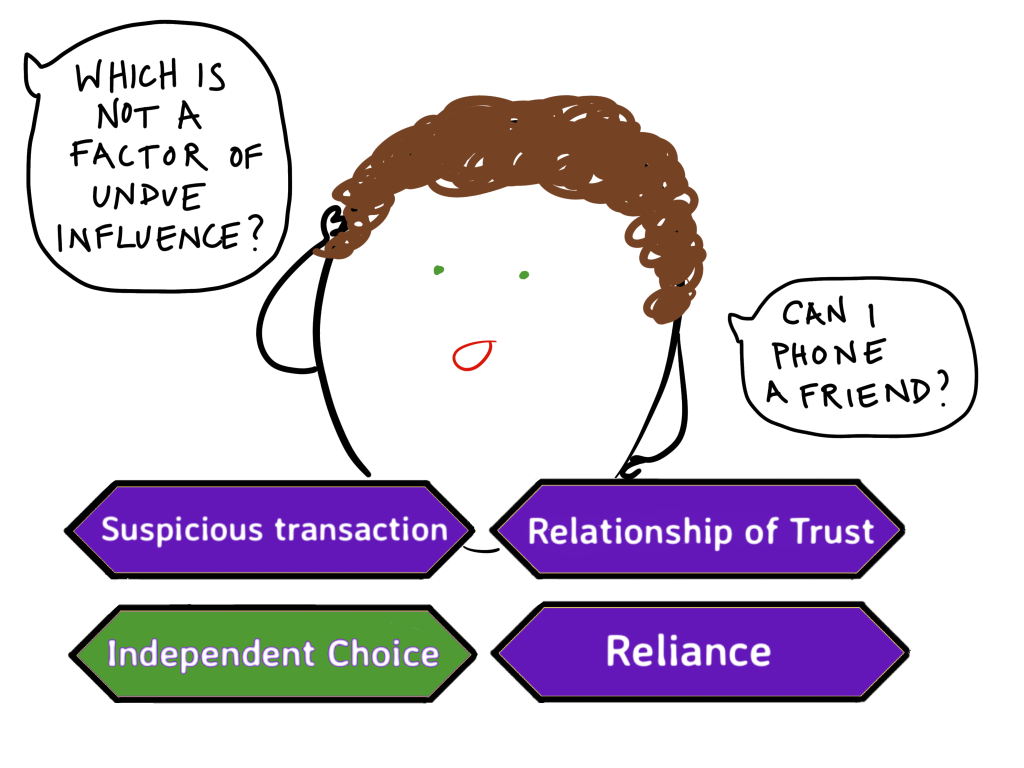

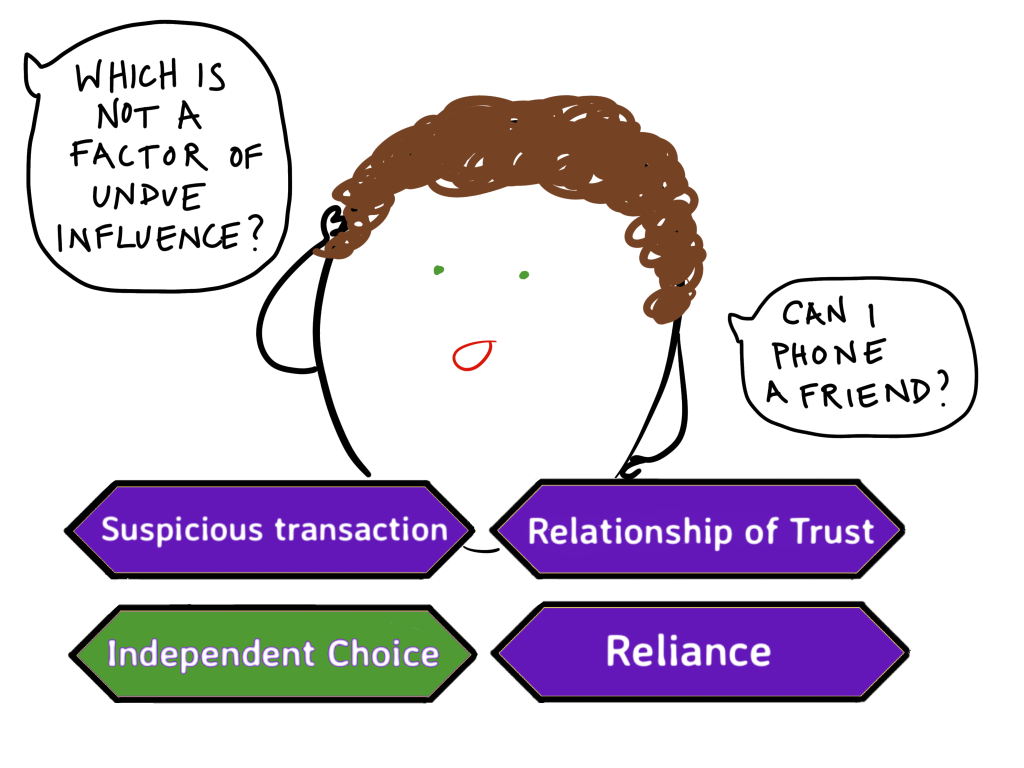

The requirements for presumed undue influence are;

- Was there a relationship of trust and confidence (i.e. influence) between the parties?

- Is there evidence that this influence was used unduly?

- Can the other party rebut this presumption?

|

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARTIES

Some relationships are recognised by the courts as ‘protected relationships’. These are always a relationship of trust and confidence with one party dependent upon the other. This includes parent and guardian, trustee and beneficiary, doctor and patient or, solicitor and client. In these situations there is an automatic and irrebuttable presumption that one party had influence over the other (Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2002) (HoL)). The presumption may also arise between a spiritual adviser and disciple (Curtis v Curtis (2011) (CoA)).

Relationships that do not automatically fall within this category are adult child and elderly parent (Avon Finance v Bridger (1985) (CoA)), husband and wife (Midland Bank v Shephard (1988) (CoA)) or bank manager and customer (National Westminster Bank v Morgan (1985) (HoL)).

If the parties do not fall into any of these categories then it must be proved that the relationship between the parties was one of trust and confidence in which one party had given a certain level of control to the other in regards to their affairs. This will depend upon the facts of the case. Unlike for protected relationships this presumption of influence can be rebutted by the other party.

UNDUE INFLUENCE

Once a relationship of influence between the parties has been established it must be shown that an undue influence was exerted. There must be something suspicious or unusual about the transaction, such as type or size, that cannot be easily explained by the parties’ relationship. The claimant must prove that the transaction ‘calls for explanation’ (National Westminster Bank plc v Morgan [1985]).

‘But if a gift [or transaction] is so large as not to be reasonably accounted for on the grounds of friendship, relationship, charity, or other ordinary motives on which ordinary men act, the burden is upon the donee to support the gift’, Lindley LJ, Allcard v Skinner (1887) (CoA)

When Miss Allcard became a nun she gave all of her property to the mother superior, Miss Skinner. When Allcard left the nunnery she requested it back, claiming undue influence. The court decided that she had been unduly influenced based on the relationship between the parties and size of the transaction but that the delay in bringing the claim barred her from reclaiming her property.

It is no longer a requirement that the transaction was to the manifest disadvantage of the party claiming undue influence (Macklin v Dowsett (2004) (CoA)) but if it was this will go towards evidence of undue influence.

REBUTTING THE PRESUMPTION

The party accused of undue influence can rebut this presumption. They will have to prove that their influence did not induce the other party into making the transaction, rather that they did it freely and independently (Re Brocklehurst (1978) (CoA)).

This can be shown by proving that the other party received independent advice, but this will depend on the facts of the case.

The absence of bad faith on the part of the defendant is not enough to rebut the presumption of undue influence (Hammond v Osborn (2002) (CoA)).

SOME EXAMPLES

In Lloyds Bank v Bundy (1975) (CoA) the court found a relationship of trust between bank and customer. Mr Bundy was a long-standing customer of Lloyds Bank, he had obviously relied upon their advice and the nature of the transaction was significant and was not to his advantage. The bank was in breach of its duty of fiduciary care in procuring the additional charge and allowing Mr Bundy to sign away his sole remaining asset without taking independent advice.

Compare this to National Westminster Bank v Morgan (1985) (HoL) in which the court held that there was no relationship of trust. Mrs Morgan had not sought specific advice from the bank manager and the transaction was readily explicable and did not give rise to suspicion.

In Goldsworthy v Brickell (1987) (CoA) a relationship of undue influence was found between the parties. Old Mr Goldsworthy owned a farm but he had fallen out with his son who helped to run it. A local farmer Mr Brickell began helping Mr Goldsworthy to run the farm and after a while effectively took over, his employees worked on the farm for free including cleaning Mr Goldsworthy’s house. Mr Goldsworthy offered him a tenancy at a very low rent and a favourable purchase option. When Mr Goldsworthy reunited with his son they took Mr Brickell to court and the arrangement was set aside by the court due to undue influence.

THIRD PARTY UNDUE INFLUENCE

Undue influence exerted by a third party can be grounds for rendering a contract voidable if the other party had actual or constructive notice of the undue influence. This has mostly arisen in cases concerning a wife who is unduly influenced by her husband to agree to a financial transaction with a bank.

The idea was first established in Barclays Bank v O’Brien (1994) (HoL) and developed in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2) (2002) (HoL).

In Barclays Bank v O’Brien, the court found that the bank had ‘constructive notice’ of the undue influence as the transaction was not to the wife’s advantage. However, this decision was criticised in Etridge, which stated that a bank must be able to have confidence that a wife’s signature is binding upon her. Lord Nicholls said that that court did not properly apply the doctrine of constructive notice in O’Brien. The law imposes no duty on a third party to check that a wife’s signature was not obtained under undue influence.

DOES THE LENDER HAVE NOTICE?

The lender will automatically have constructive notice of possible undue influence if a wife (or other co-habitee) is standing surety for their husband’s debt and there is no material advantage for the wife in the transaction – i.e. it will only benefit the husband in his personal capacity (CIBC Mortgages v Pitt (1994) (HoL)).

The bank had been told by the couple that the loan was for paying off a joint mortgage and buying a holiday home. This was in fact untrue and the money was intended to pay off the husband’s debts. The court held that the bank had not had constructive notice, they had relied upon the information given to them and were not required to dig deeper.

TAKING REASONABLE STEPS

If the bank has constructive notice of possible undue influence they must take reasonable steps to satisfy themselves that the person taking out the loan understands the practical implications of the transaction.

The bank can do this by ensuring that independent legal advice has been given to that person and that the practical implications of the proposed transaction have been made clear to the potential victim of undue influence (Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Etridge (No 2) (2002) (HoL)).

However, this will not automatically be enough to fulfil the requirement to take reasonable steps, the bank must make sure that sufficient steps have been taken to free the donor from any potential undue influence.

‘It is necessary for the court to be satisfied that the advice and explanation by, for example, a solicitor, was relevant and effective to free the donor from the impairment of the influence on his free will and to give him the necessary independence of judgment and freedom to make choices with a full appreciation of what he was doing’ (Niersmans v Pesticcio (2004) (CoA)).