JUMP TO: SETTING STANDARD | CHARACTERISTICS OF DEFENDANT | BREACH | REVISE | TEST

STANDARD OF CARE & BREACH

If a duty of care has been found then the court must consider whether that duty has been breached. This is a two part process. Firstly the court must decide to what standard of care the defendant should be held. This is a question of law. Then the court must decide whether the defendant has fallen below that standard, i.e. have they breached their duty? This is a question of fact.

SETTING THE STANDARD

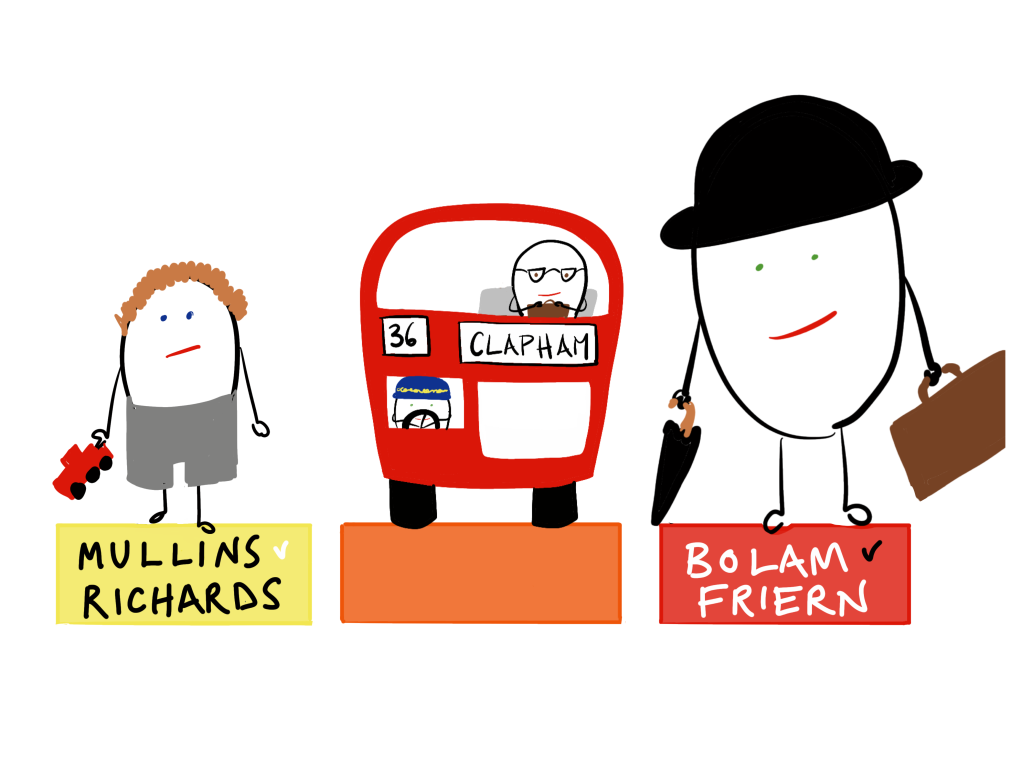

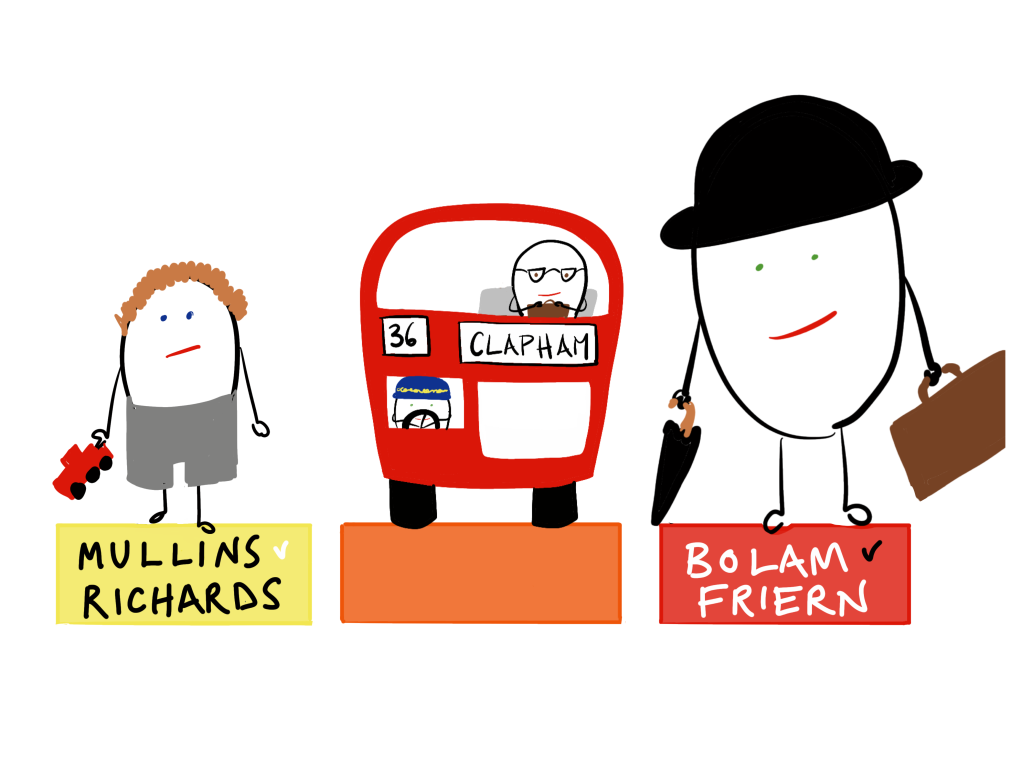

The general standard of care owed by the defendant is that of the ‘reasonable man’. One of the most famous explanations of this term is from Hall v Brooklands Auto Racing (1933) (CoA); the reasonable man is ‘the man on the Clapham Omnibus, or…the man who takes the magazines at home, and in the evening pushes the lawn-mower in his shirt sleeves’, Green LJ.

This description changes with the times but in essence it is an objective standard fashioned from what the ordinary person would or should have done in the same circumstances as the defendant. The reasonable man is not expected to have foreseen and been able to avoid every single risk. They must just have done what was reasonable to avoid danger to others. In Etheridge v East Sussex County Council (1988) a teacher made a claim against the school when she fell down some steps after being hit by a basketball. The court found that there were sufficient measures in place to avoid such risks (e.g,. fences around the basketball courts) and that the school had done what was reasonable. They were not expected to have been able to avoid all risk.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DEFENDANT

In general the personal characteristics of the defendant will not affect the standard to which they are held. Instead the standard will be set based on the act committed not the person who performed the act.

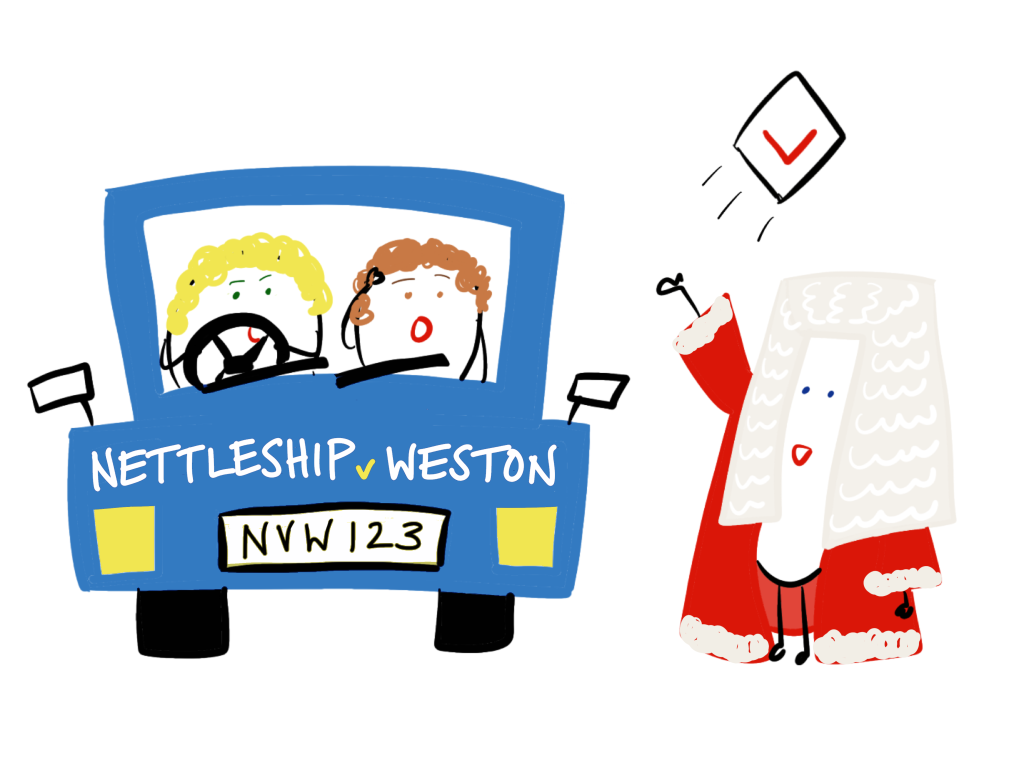

For example, all people driving will be held to the standard of the reasonable driver despite any personal characteristics Nettleship v Weston (1971) (CoA).

A learner driver crashed injuring her instructor. When a case was brought against her by the instructor she argued that a lower standard of care should be applied as she was a learner. This was rejected by the courts, she would be held to the standard of a reasonable driver. However, to reflect the situation the claimant’s damages were reduced by 50% for contributory negligence because, as the instructor, they also had some control over the car.

The reasoning given for this by the court was that having different standards could lead to confusion about what standard a claimant should be held to and what characteristics should be taken into consideration. Also any victim unlucky enough to be injured by a learner driver may then not be able to claim because the standard was lower and there was no breach.

ACTION NOT DEFENDANT

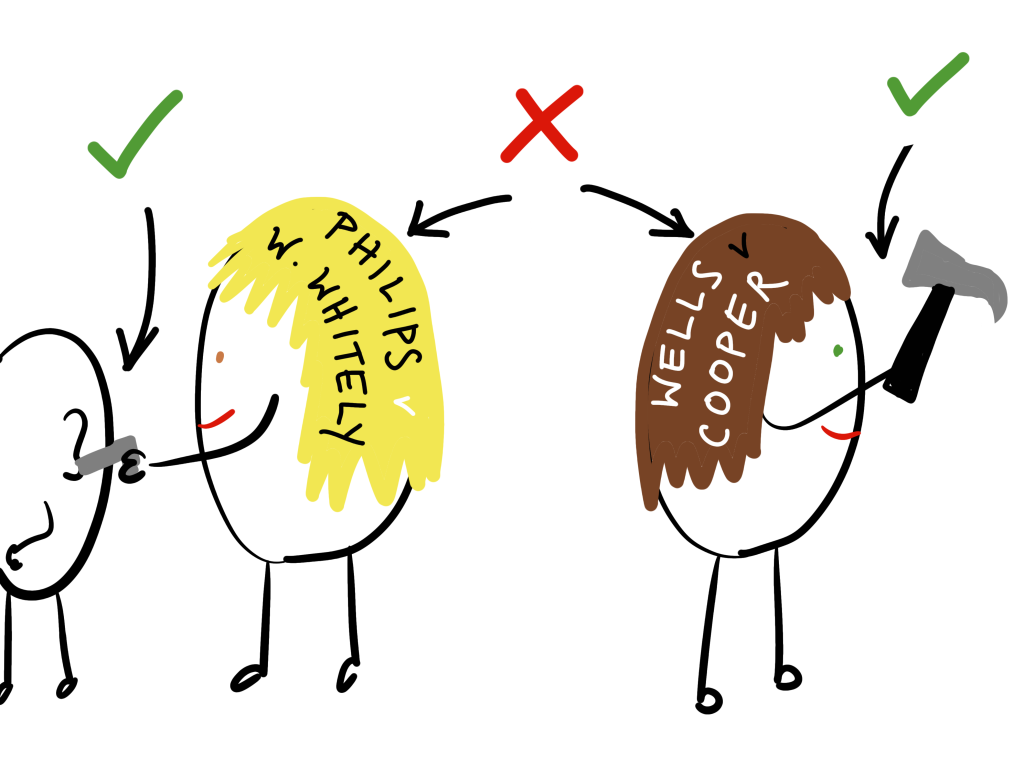

However, the exact standard will depend upon the facts of the case and the action being performed rather than necessarily the characteristics of the defendant.

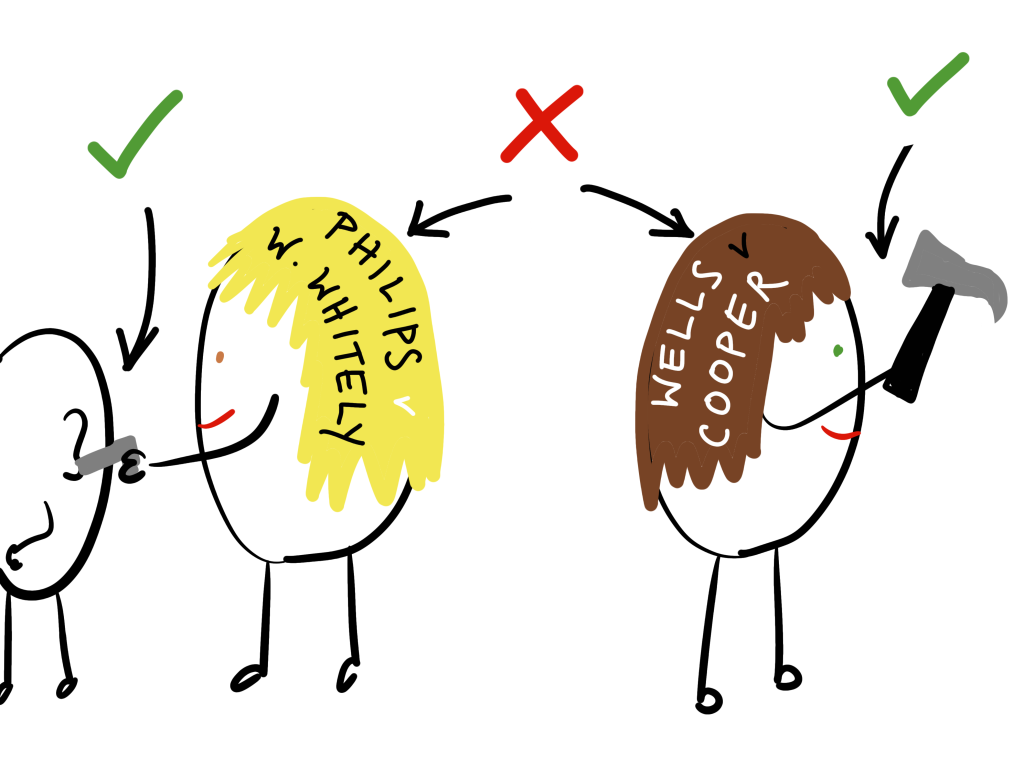

| In Philips v William Whiteley (1938) a jeweller who performed an ear piercing that became infected was held to the standard of a reasonably competent jeweller performing an ear piercing and not the standard of a surgeon (who might have avoided an infection). However, if a surgeon had performed the ear piercing they would still be held to the professional standard of a surgeon and not the lower standard of a jeweller. |

In Wells v Cooper (1958) (CoA) a DIY amateur enthusiast who had fitted a door handle that broke and injured the claimant was only held to the standard of a reasonable man doing DIY and not a professional builder. However, if he had performed more complicated work, e.g. rewiring, he may have been held to a higher standard. |

CHARACTERISTICS THAT ARE TAKEN INTO CONSIDERATION

There are some characteristics of the defendant that will be taken into account despite the act they were carrying out. These include whether the defendant is a professional or a child

PROFESSIONALS

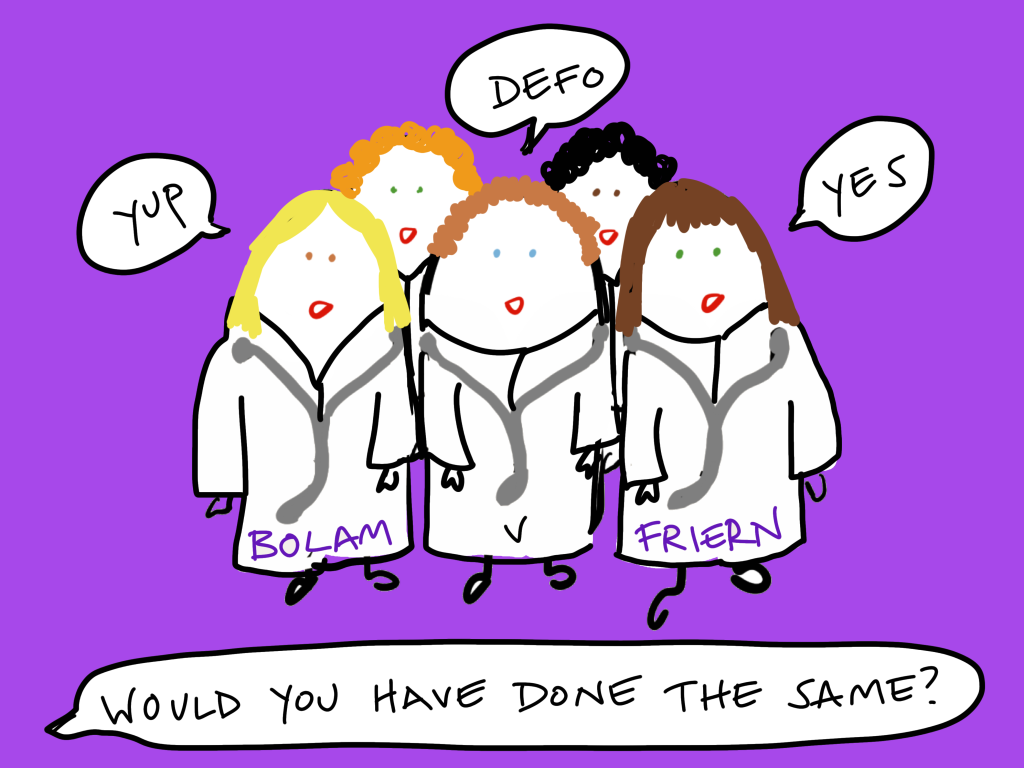

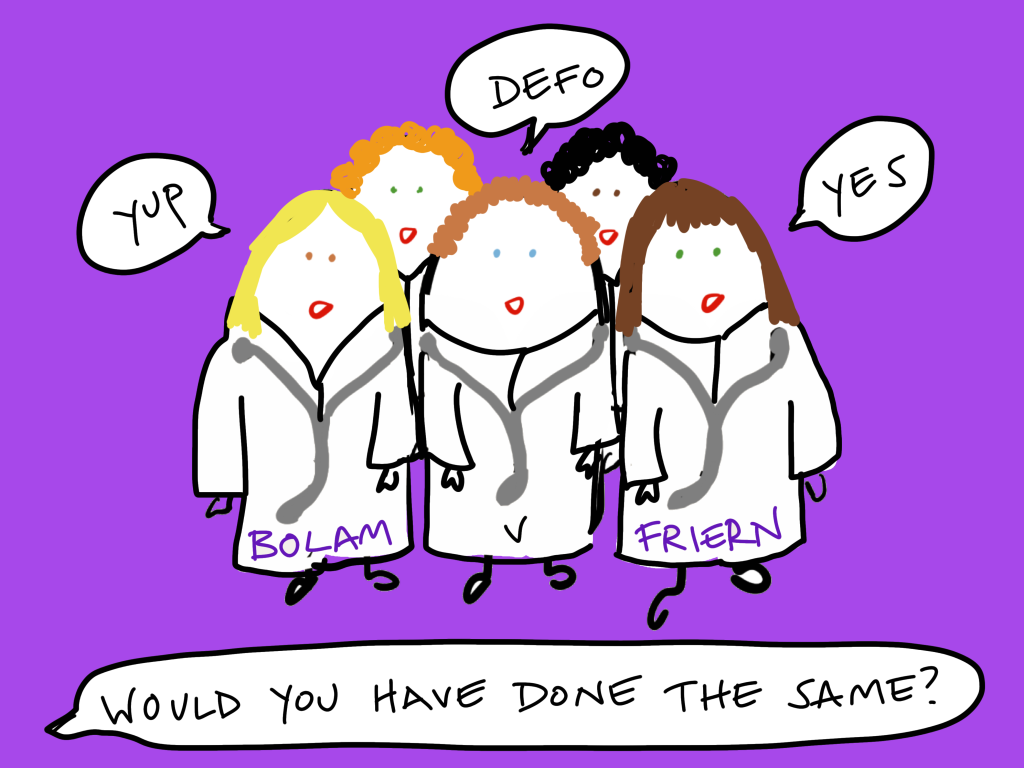

Professionals will be held to a different standard than that of the reasonable man. The standard will be of the reasonable professional, i.e. the reasonable doctor (Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) (HC)). ‘A man need not possess the highest expert skill at the risk of being found negligent…it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular act’.

There can be different standards within a profession, for example a GP would not be held to the same standard as a surgeon, unless they were performing surgery. However, like a learner driver a junior surgeon will be held to the same standard as an experienced surgeon (Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority (1987) (HoL)).

COMMON PRACTICE

When it comes to the standard to which a professional should be held the courts are willing to rely to some degree on an industry standard. For example in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) (HC) the defendant argued that their actions would have also been taken by other medical professionals. The court will consider if ‘he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a reasonable body of medical men skilled in that particular art’.

This was qualified somewhat in Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority (1998) (HoL); if the practice is deemed illogical by the court then it will not matter if it is common practice in the profession.

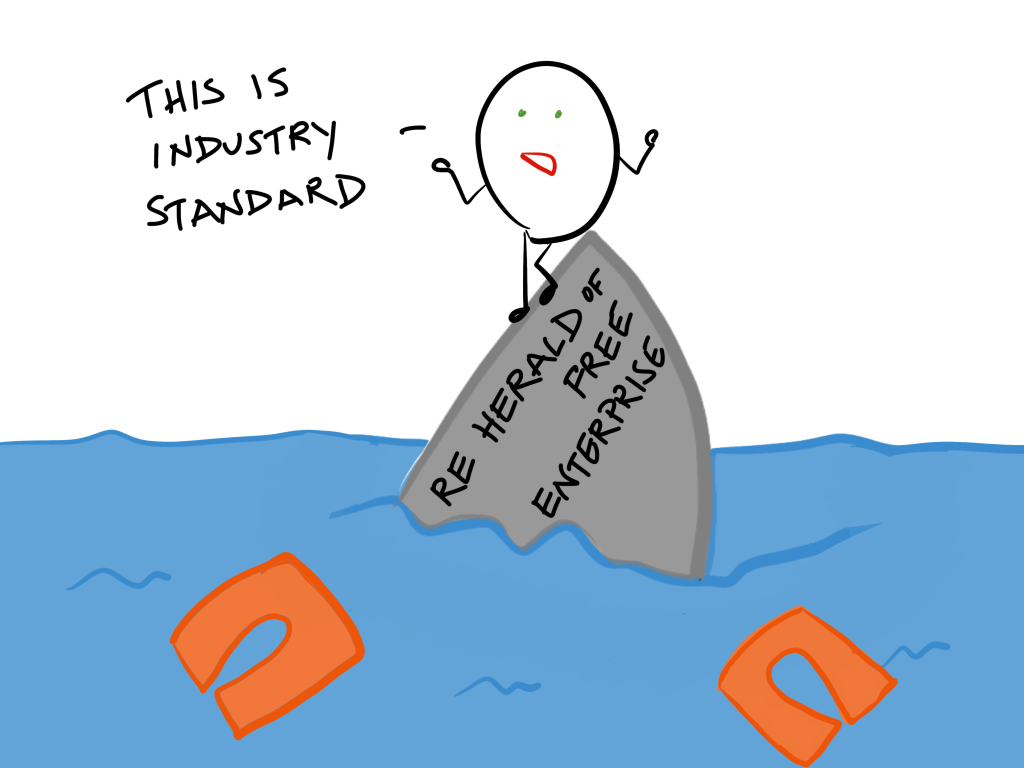

This is also true if the common practice is negligent (Re Herald of Free Enterprise (1987)).

A car ferry sunk killing many people. The company argued that it was common practice to set sail without the door being fully closed to save time. This was rejected by the courts as a negligent practice, it did not matter whether everyone else also did the same.

CHILDREN

Children are also held to a more specific standard, that of a reasonable and careful child of the same age as the defendant (Mullins v Richards (1998) (CoA)). In this case a schoolgirl was injured when a ruler that she was playing with broke and hit the defendant in the eye. It was held that a reasonable and careful 15 year old would not have foreseen this risk.

ILLNESS

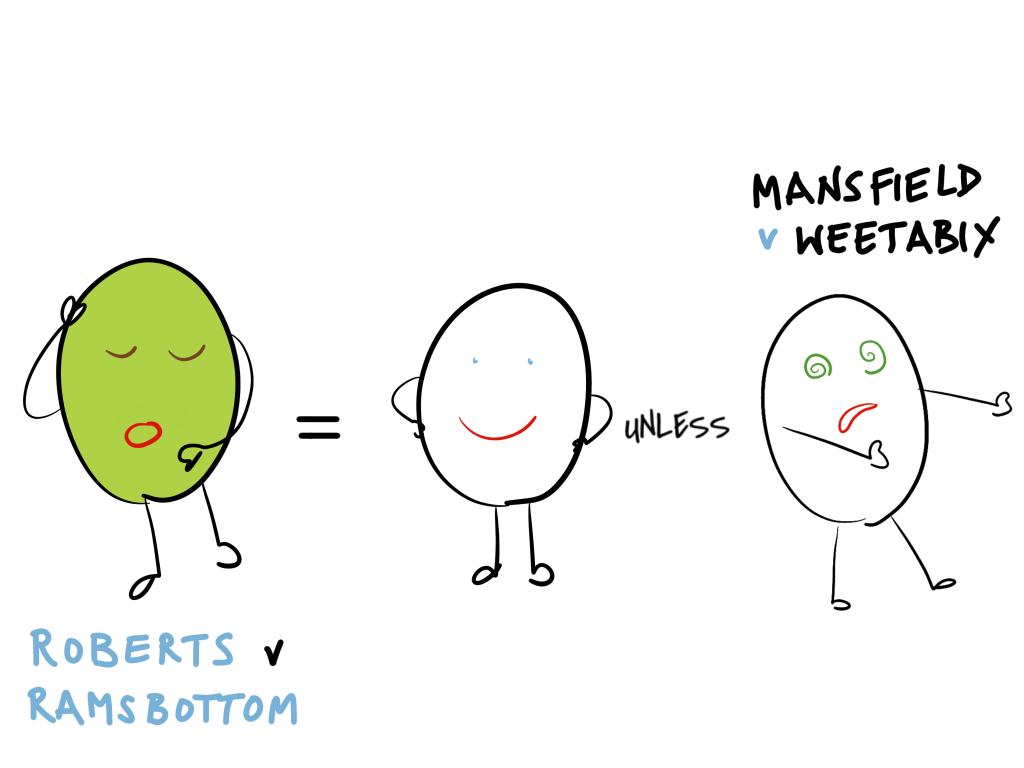

Will the standard of care be lowered for those suffering from an illness or disability? Compare the cases below…

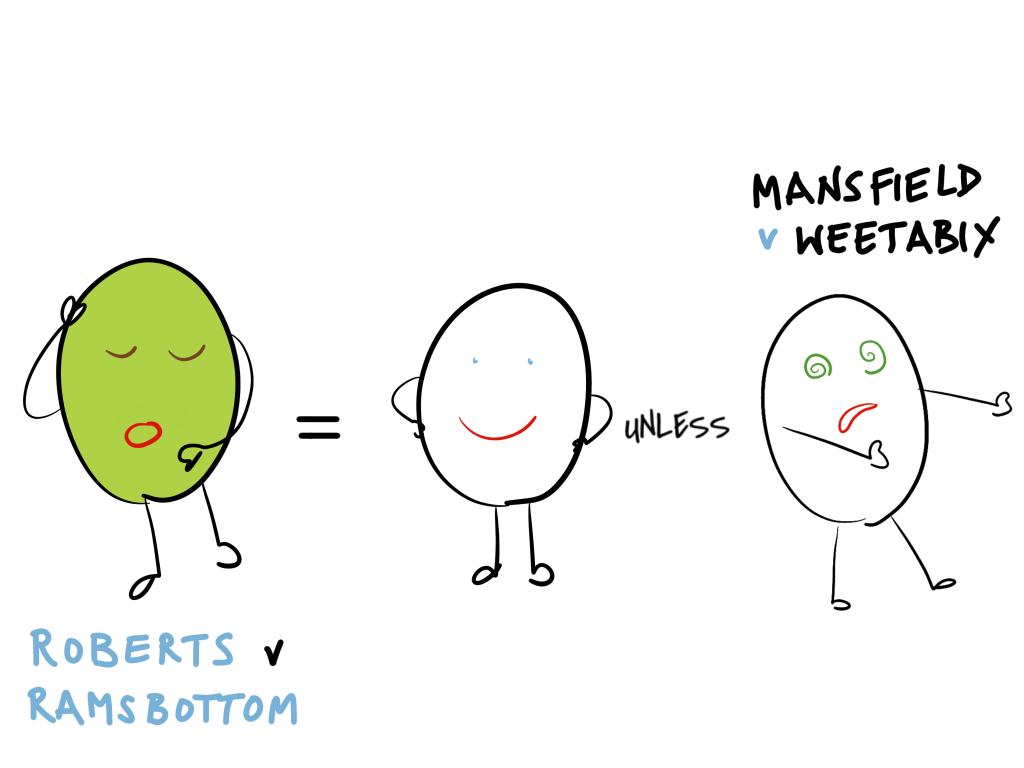

| In Roberts v Ramsbottom (1980) (HC) a man unknowingly suffered a stroke before driving. He was aware that his health was impaired but did not consider himself unfit to drive. Whilst driving his condition deteriorated but he did not stop even when he clipped a van before eventually crashing into the claimant’s car. His illness did not lower the standard and he was held to the standard of a reasonably competent driver who should have ceased driving when he felt unwell. |

In Mansfield v Weetabix (1998) (CoA) the driver crashed after a gradual lowering of his blood sugar level that affected his brain function. There was no evidence to suggest that he knew this was happening or could have done anything about it. His illness was taken into account and he was held to the standard of a reasonably competent driver who was unaware that he was suffering a condition that impaired his ability to drive. |

In Dunnage v Randall (2015) (CoA) the court confirmed that the defendant’s medical state, whether physical or mental, will not be taken into consideration to lower the standard of care owed unless it can be shown that the condition entirely eliminates all responsibility. For example, a state of automatism or sleep walking, or if the defendant suffered ‘some entirely unheralded, unexpected and unforeseen incapacitating attack’. In this case an man, whose post-mortem identified that he had been suffering with schizophrenia, had set fire to himself subsequently injuring his nephew. The uncle’s mental state would not be taken into consideration when setting the appropriate standard of care because, although ill, he had been in control of his actions.

BREACH

When deciding whether the defendant has breached their standard of care by not avoiding the risk, or not taking reasonable precautions to avoid the risk, the court will take into consideration the probability of the injury occurring, the seriousness of the risk, the cost of taking precautions and the social value of the activity.

Defendants cannot be expected to avoid risks that are unknown at the time. Their actions will be judged against the available knowledge at the time of the act (Roe v Ministry of Health (1954) (CoA)).

Roe was paralysed by an injection of anaesthetic. It later transpired that the anaesthetic had been contaminated because of microscopic cracks in the vials it was kept in. This fact was unknown to the medical profession at the time. Although it was known by the time of the court case this could not be taken into consideration.

PROBABILITY

The more likely an event the more likely it is that the defendant will be held liable for it. In other words, a defendant cannot be expected to avoid every single risk so the smaller the risk the less likely a defendant will have breached the standard of care if it occurs (Bolton v Stone (1951) (HoL)).

The claimant was hit on the head by a cricket ball flying over from the cricket pitch next to her house. The court found that the cricket club had taken sufficient precautions to avoid this risk (a high fence surrounded the pitch) and the risk was very small (a ball travelling over the fence had only happened six times in 30 years). A reasonable cricket club could not be expected to take precautions against such a small risk. They had not breached the required standard of care.

Compare this to Pearson v Lightning (1998) (CoA) when a man was hit by a golf ball. The court held that the risk of hitting someone when making a difficult shot over an area in which other players were standing was big enough that the defendant should reasonably have foreseen it and avoided it.

SERIOUSNESS OF INJURY

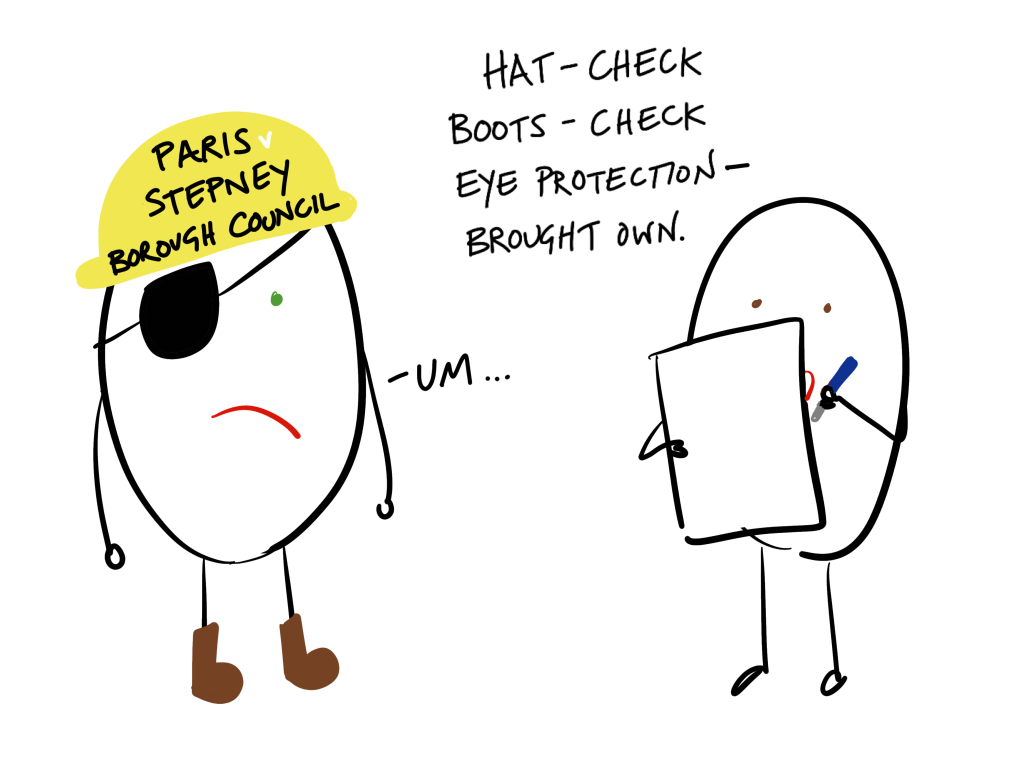

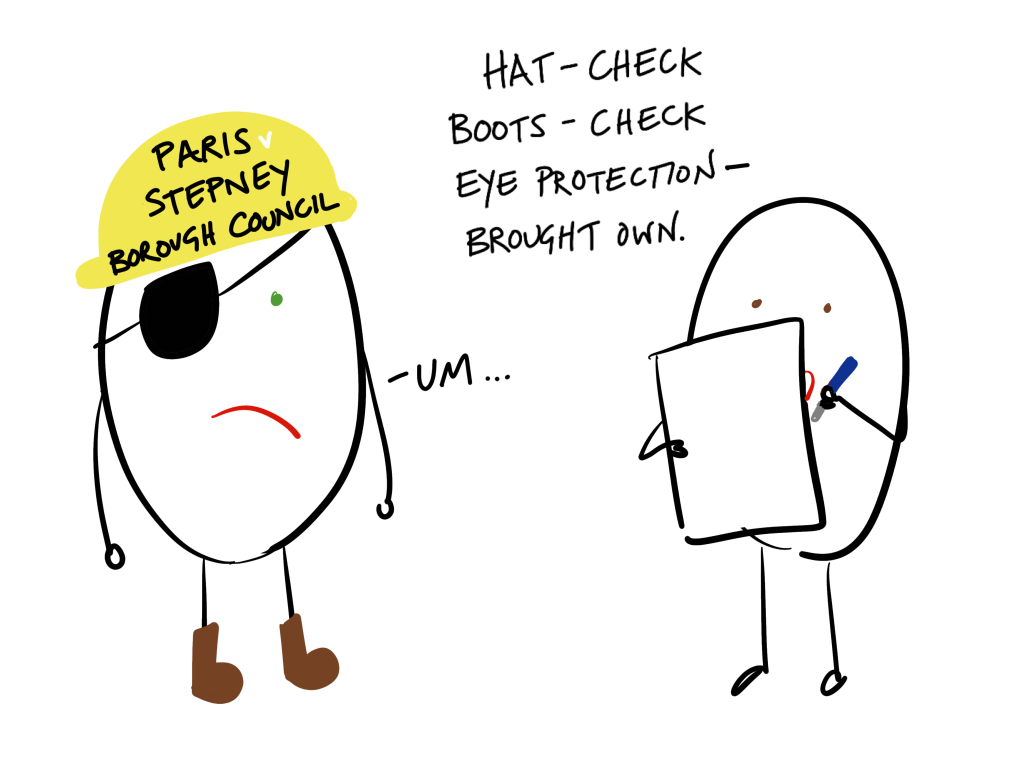

If it was, or should have been, known to the defendant that the consequence of a specific risk would be serious injury to the claimant then they may be liable for even a small risk (Paris v Stepney Borough Council (1951) (HoL)).

Paris was blind in one eye but was not provided with protective goggles at work. A piece of metal damaged his good eye in a work-related accident. Although the risk of this happening was small because the consequences would be very serious for the claimant the defendants had fallen below the standard of care expected.

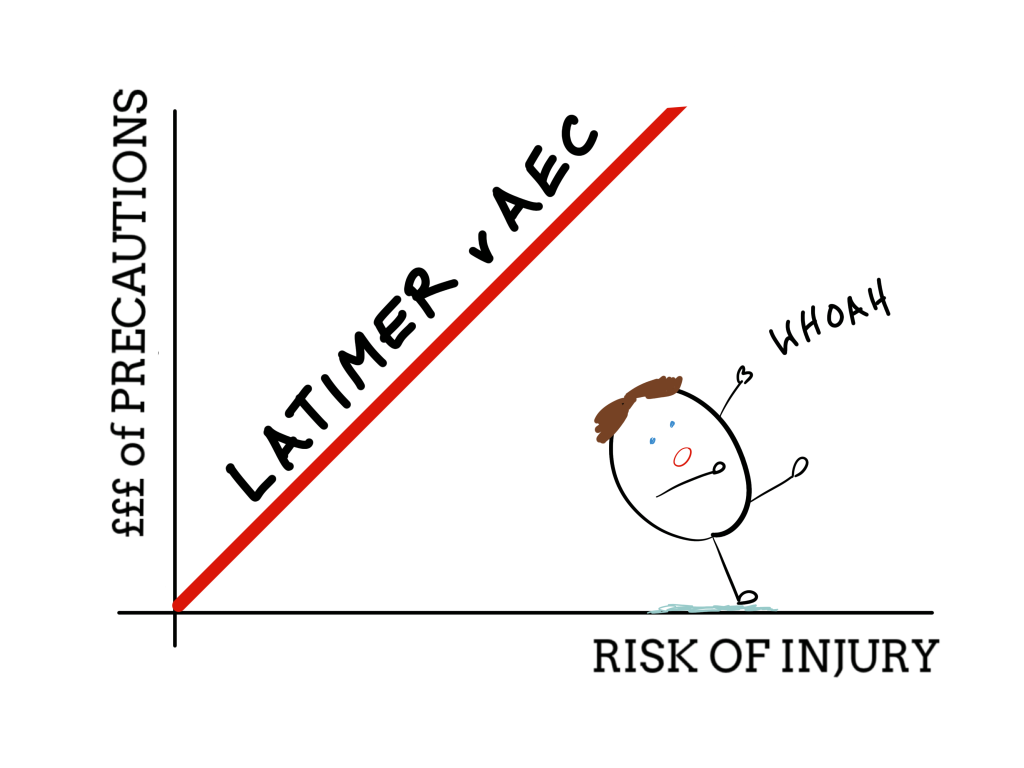

COST OF PRECAUTIONS

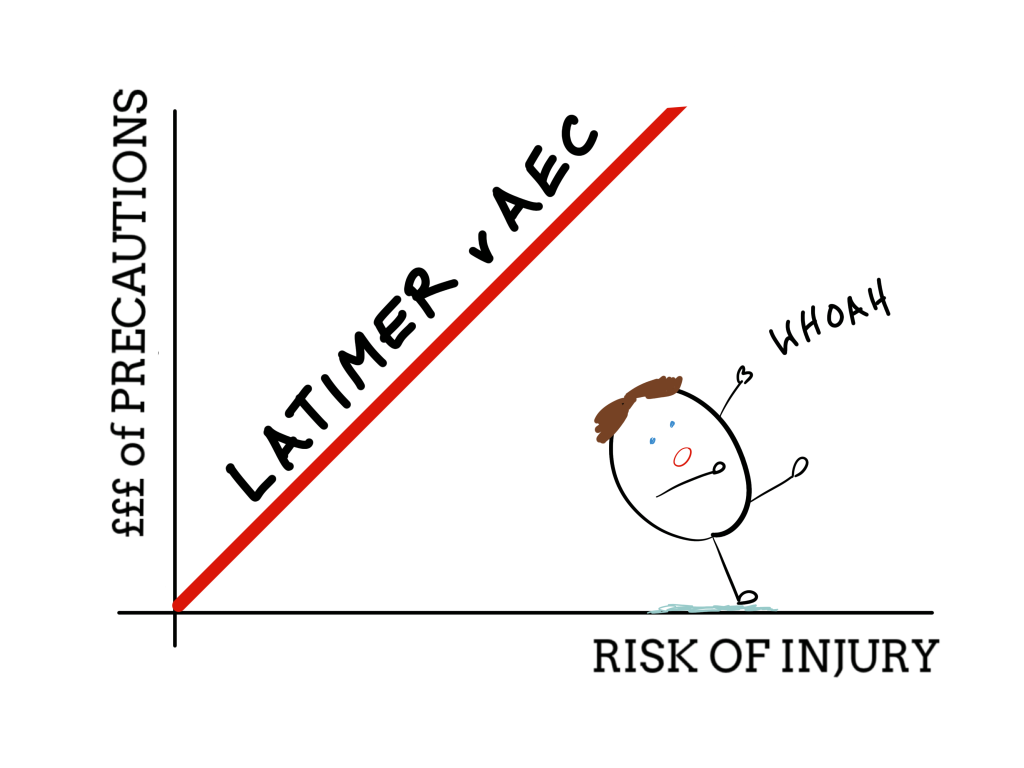

The courts will also weigh up whether the cost of avoiding a risk is proportionate to the risk itself (Latimer v AEC (1953) (HoL)).

The claimant, who was employed by the defendant, slipped over on a wet floor sustaining an injury. The floor had been covered with sawdust to reduce the risk of this happening. The only way to eliminate the risk entirely would have been to shut the factory, this was deemed an expense out of proportion to the risk.

SOCIAL VALUE

The social value of the defendant’s activity will be considered. Someone acting altruistically in the heat of the moment will be less likely to have breached the standard of care (Watt v Hertfordshire County Council (1954) (CoA)).

A fireman was injured by heavy machinery that had not been properly secured in the back of the vehicle. The vehicle was on its way to an emergency. The court held that in the circumstances it was reasonable for the defendant to have taken what was a small risk as it was outweighed by the public good of getting to the emergency quickly. The claimant’s case failed.

However, in Ward v London County Council (1938) a fire engine that ran a red light and injured the claimant had breached the standard of care owed to the claimant. The risk of such an action was too high and did not outweigh the potential public good.

The Social Action, Responsibility and Heroism Act 2015 enshrined into law that when the courts are looking at breach they must consider whether the breach occurred when the defendant was ‘acting for the benefit of society or any of its members’ (section 2), whether they ‘demonstrated a predominantly responsible approach towards protecting the safety or other interests of others’ (section 3) or if the defendant ‘was acting heroically by intervening in an emergency to assist an individual in danger’ (section 4).

How is this different to the rule from Watt v Hertfordshire County Council? Legally it adds little apart from the element of ‘heroism’ which is very difficult to define in a legal context. This Act has not yet been considered in a legal case but has been criticised for replicating existing common law and for being more of a political statement made by the government at the time than necessary addition to the law.

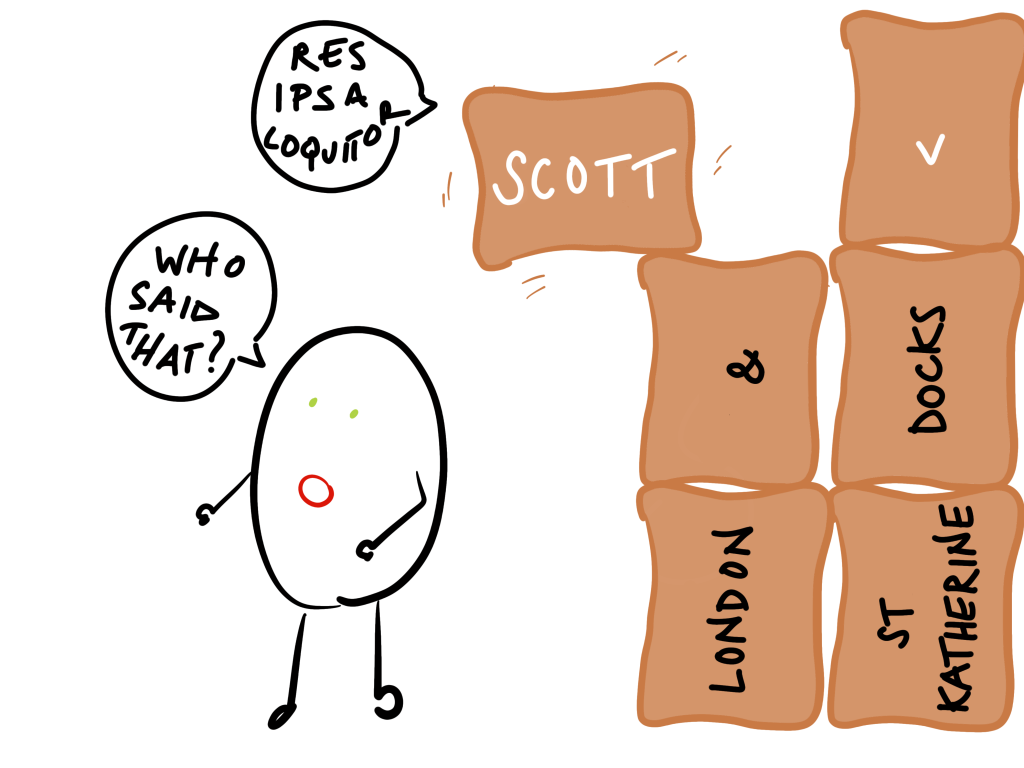

RES IPSA LOQUITUR

Res ipsa loquitur means ‘the situation speaks for itself’. This doctrine can be used to show breach when there is not enough evidence to prove negligence but negligence can be inferred from the situation. The courts will only use this doctrine sparingly, in the most extreme and obvious cases. The claimant must show that the defendant was in control of the situation, the accident would not normally have occurred without negligence and the exact cause of the accident is not known. This creates a rebuttable presumption and the defendant must provide evidence to the contrary if they wish to rebut it (Scott v London & St Katherine Docks (1865) (Court of Exchequer)).

The claimant was injured when bags of sugar fell on him in the defendant’s warehouse. Although it was not possible to prove exactly how the accident had occurred it was unlikely that the accident would have happened if not for the negligence of the defendant in securing items in the warehouse.

In Mahon v Osborne (1939) (CoA) the fact that a swab was left inside a patient after an operation was an example of res ipsa loquitur. Or Cassidy v Minister of Health (1951) (CoA) in which the claimant had an operation to correct two stiff fingers and woke up with four stiff fingers.