JUMP TO: FACTUAL CAUSATION | APPORTIONING LIABILITY | LEGAL CAUSATION | REVISE | TEST

CAUSATION

Once it has been established that a duty of care was owed and that the standard of care was breached, the court must consider whether the breach caused the damage. This requires a consideration of both factual and legal causation.

FACTUAL CAUSATION

Factual causation is based on the facts of the case; was it the breach that led to the damage? The claimant must prove that on the balance of probabilities, ‘but for’ the breach the damage would not have happened, i.e. it is the most likely cause and over 50% responsible for the damage.

The ‘but for’ test arose in the case of Cork v Kirkby MacClean (1952) (CoA).

‘But For’ test

Cork died when he had an epileptic fit and fell from a high platform at the factory where he worked. His employer did not know of his condition or the fact that his doctor had told him not to work at heights. Cork’s widow sued his employer for negligence based on the fact that the platform had no railings. The defendant argued that it was not the lack of railings that had caused his death but his epileptic fit. The court disagreed; ‘but for’ the lack of railings Cork would not have died and therefore the defendants were liable for his death. However, the damage awarded were reduced to reflect that they did not know about his epilepsy.

In Barnett v Kensington and Chelsea Hospital (1969) (HC) a man died from arsenic poisoning. When he arrived at hospital feeling unwell he was not examined by the doctor but told to go home and see his GP. The hospital was not liable for his death because it was proven that even if he had been examined he would still have died. ‘But for’ the defendant’s breach he would still have suffered the damage.

MULTIPLE CAUSES

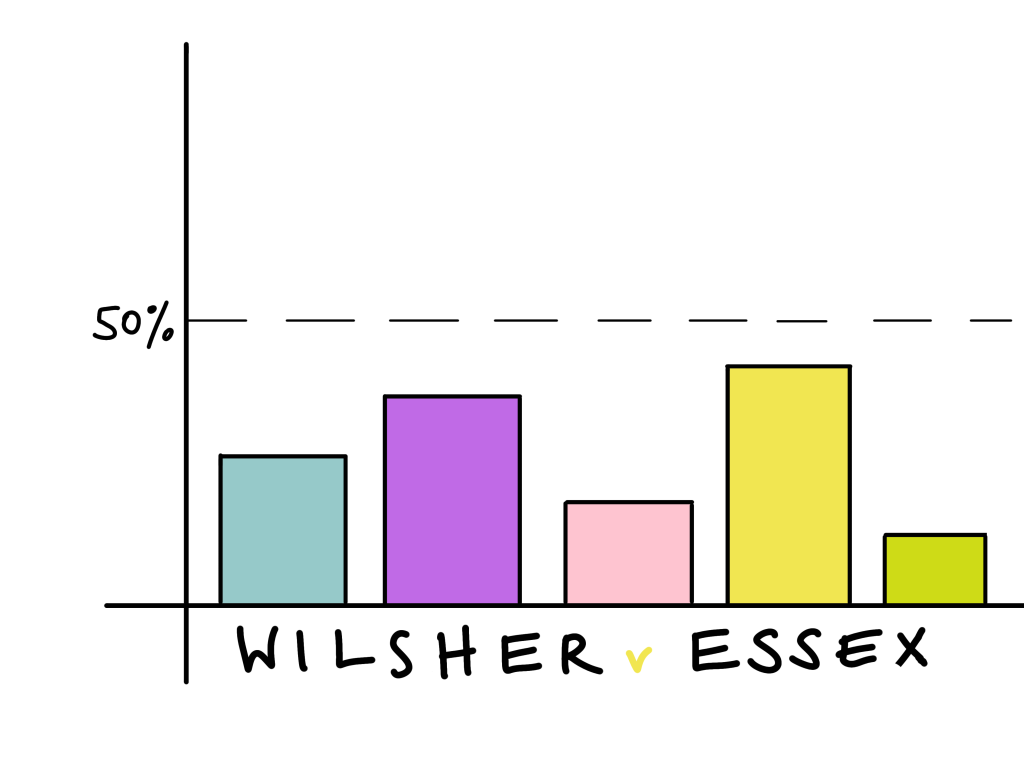

If there are multiple, potential independent causes the claimant must still prove, using the ‘but for’ test, that the negligent act caused the breach on the balance of probabilities, i.e. that it was over 50% likely to have been the cause. When there are multiple potential causes this can be very difficult, especially when the other causes are non-tortious.

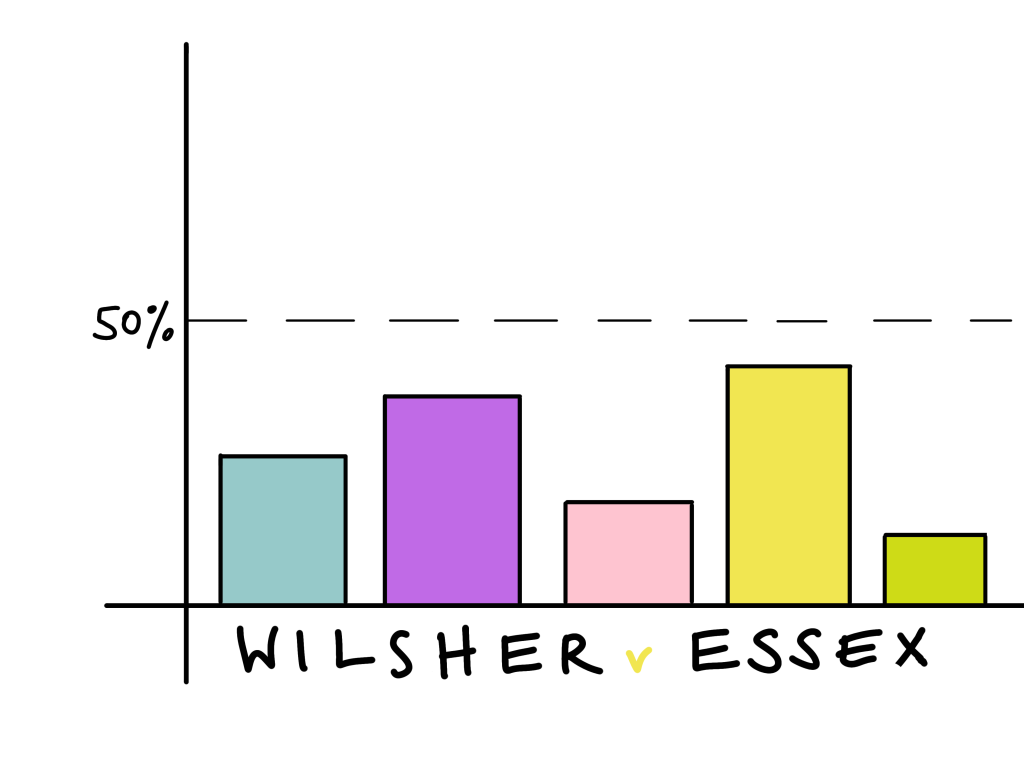

A good example of this is Wilsher v Essex AHA (1988) (HoL).

Wilsher was born prematurely and developed an incurable retinal condition.. There were five potential reasons why this might have happened. One was the negligent act of the doctor who twice gave him too much oxygen but the others were all connected to non-negligent reasons such as being premature. The hospital could not be held liable because the claimant was unable to prove that the negligence was more than 50% likely to be the cause of the damage or that ‘but for’ the doctor’s negligence the baby would not have suffered damage to its sight.

EXCEPTIONS TO ‘BUT FOR’ TEST

In some cases the courts have found ways around the ‘but for’ test when its use would have led to an unfair result such as the claimant receiving no compensation even though the defendant had acted negligently.

MATERIAL CONTRIBUTION TO DAMAGE

Here the claimant can prove causation if the defendant’s breach materially contributed to the claimant’s actual harm. For instance, if the claimant was innocently exposed to the harm but the defendant also exposed the claimant to the harm and this brings about a cumulative effect that increases the severity of the claimant’s harm. Using the ‘but for’ test the defendant would not be liable bringing about an unjust situation in which the claimant cannot be compensated even though the defendant has acted negligently.

The test was first put forward in Bonnington Castings v Wardlaw (1956) (HoL).

The claimant was exposed to dust at work which caused lung disease. The court found that some exposure to this dust was an inevitable part of the job, ‘good dust’, but there had been extra dust in the atmosphere because the employer had negligently not conformed to regulations, this was ‘bad dust’. The lung disease was caused by the accumulation of dust in the lungs and it was not possible to ascertain whether the bad dust caused the injury or he would have suffered anyway from the good dust. Using the ‘but for’ test the claim would have failed. However, the court found causation by holding that the defendant’s negligence had ‘materially contributed’ to the harm and therefore the employer was liable for all of the claimant’s illness.

A more recent case is Bailey v Ministry of Defence (2008) (CoA). Bailey underwent an operation to remove gallstones. A negligent lack of post-operative care meant that she had to undergo further procedures. She also contracted pancreatitis (not due to any negligence). These factors led to her becoming extremely weak which caused her to. She subsequently choked on her own vomit causing cardiac arrest and brain damage. The claimant’s argument was that had she not been very weak she would have been able to stop herself choking. It was impossible to establish from the evidence that ‘but for’ the negligent lack of post-operative care the damage would not have occurred. However, the judge at first instance held that the negligent act had materially contributed to the damage and this was upheld by the Court of Appeal.

What is a ‘material’ contribution to the damage? As specified in Bonnington Castings v Wardlaw (1956) (HoL) material means anything more than de minimis or minimal, or more than statistically insignificant. This will be decided by the court on the facts of the case.

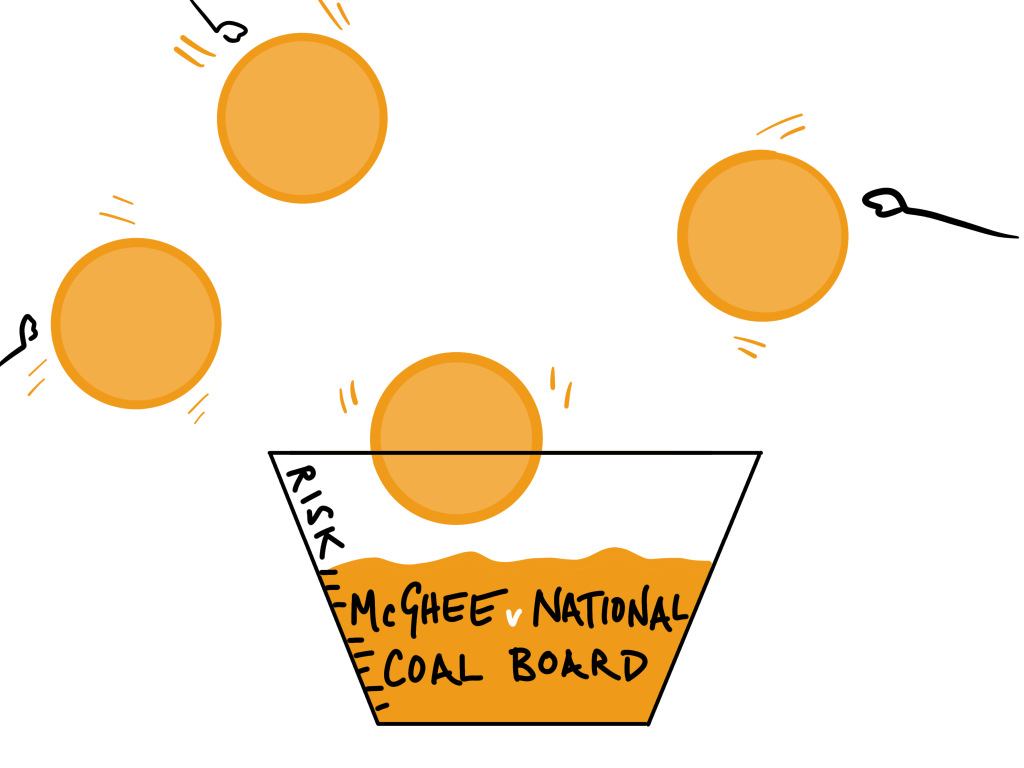

MATERIAL CONTRIBUTION TO RISK

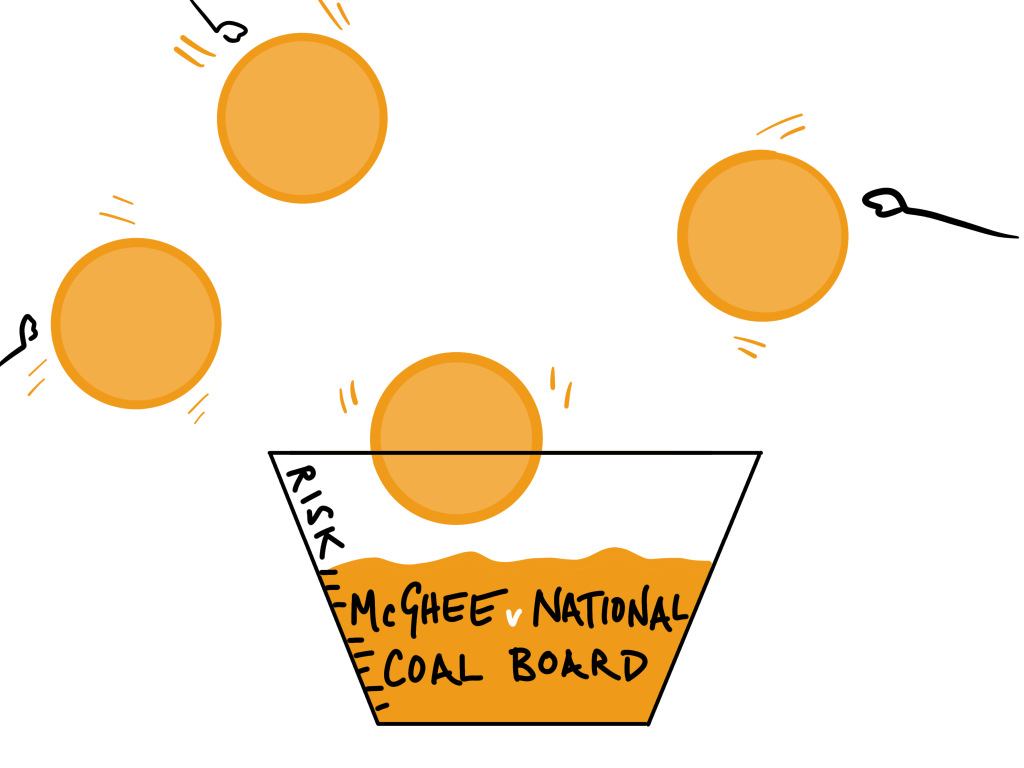

A similar, but subtlety different, test can be used by the courts when the multiple potential causes are not cumulative but separate, either caused by one defendant or multiple, and the claimant can prove a sufficient causal link between the defendant’s breach and a material contribution to the risk of suffering the harm (McGhee v National Coal Board (1973) (HoL)).

McGhee suffered from dermatitis. Both the ‘good’ brick dust that he was exposed to at work and the ‘bad’ brick dust that stayed on him between work and home (caused by the negligence of the employer who did not provide washing facilities) could have caused the damage. Unlike the lung disease in Bonnington dermatitis is not caused by a cumulative build up of dust but would have been caused by one exposure but it was impossible to tell whether it was the good dust or the bad. The court departed again from the ‘but for’ test and held that the defendant’s negligence had ‘materially increased’ the risk of harm occurring and they were therefore liable.

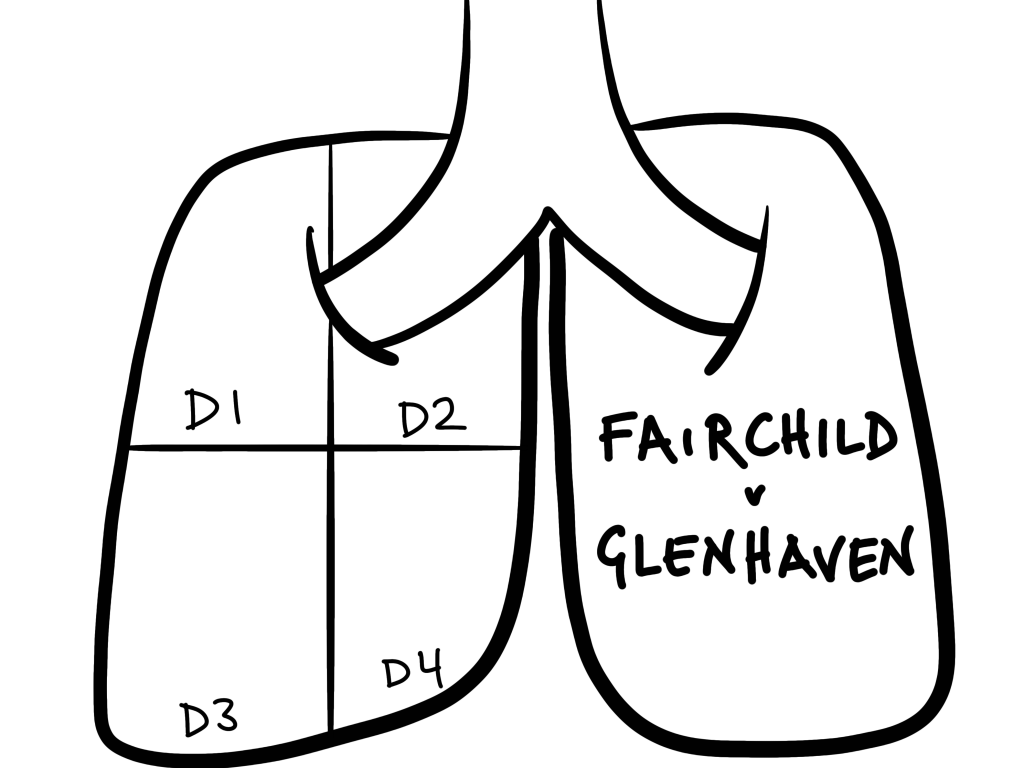

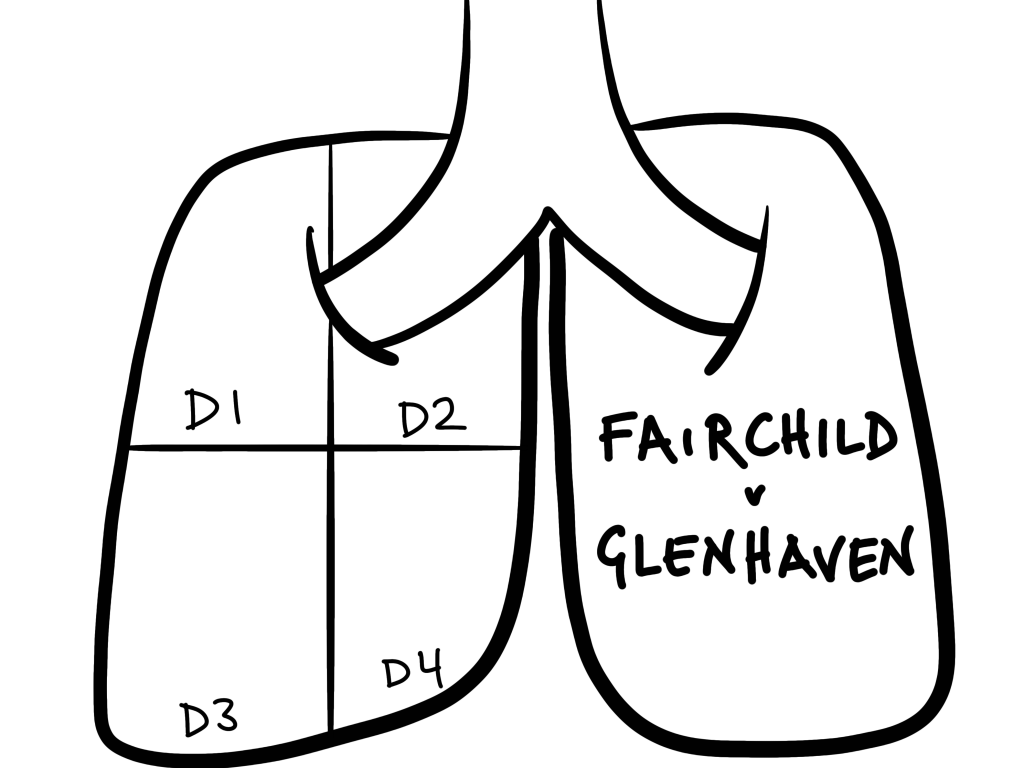

This was revisited in Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services (2002) (HoL) a case that concerned mesothelioma, a fatal lung disease caused by exposure to asbestos. It can be caused by a single exposure rather than an accumulation and the effects may not manifest themselves for decades. This means that if a claimant has worked for several different employers who all negligently exposed them to asbestos it is scientifically impossible to ascertain which defendant caused the harm. The court held that, even though only one defendant could technically be responsible for the exposure to asbestos that caused the damage, in this instance each additional exposure to asbestos materially increased the risk of contracting the disease, therefore all of the defendants were jointly and severally liable. For more on apportionment of liability see below.

SINGLE AGENT

How does this differ to Wilsher v Essex AHA (1988) (HoL)? In order for the material increase in risk test to be available there must be only one type of ‘agent’ that could have caused the damage even if the claimant was exposed to this agent in several different ways. So in McGhee it was dust (‘good’ and ‘bad’ dust) but in Wilsher the potential causes of the injury were all different ‘agents’; being premature, too much oxygen, etc. This rule was added by Lord Bingham in Wilsher.

In Barker v Corus (2006) (HoL) the court held that it did not matter by what mechanism the claimant was exposed to the agent as long as it was the same agent. The material increase in risk test was still available even if one of the exposures had been when Barker was self-employed and exposed himself to asbestos. The example given by Lord Hoffmann of when the material increase in risk test would not be applicable because the potential ‘agents’ were all different was if someone had contracted lung cancer and it could have been caused by either asbestos, exposure to another carcinogen or smoking. The mechanisms of exposure do not all have to be tortious. In Sienkiewicz v Greif (2011) (SC) the claimant was exposed to asbestos dust both at work and from asbestos in the air caused by living close to Ellesmere port.

Only if using the material contribution to risk test do the agents have to be the same. If using the material contribution to damage test the agents do not have to be the same. This was stated in the recent High Court case of Dr Sido John v Central Manchester and Manchester Children’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (2016) (HC).

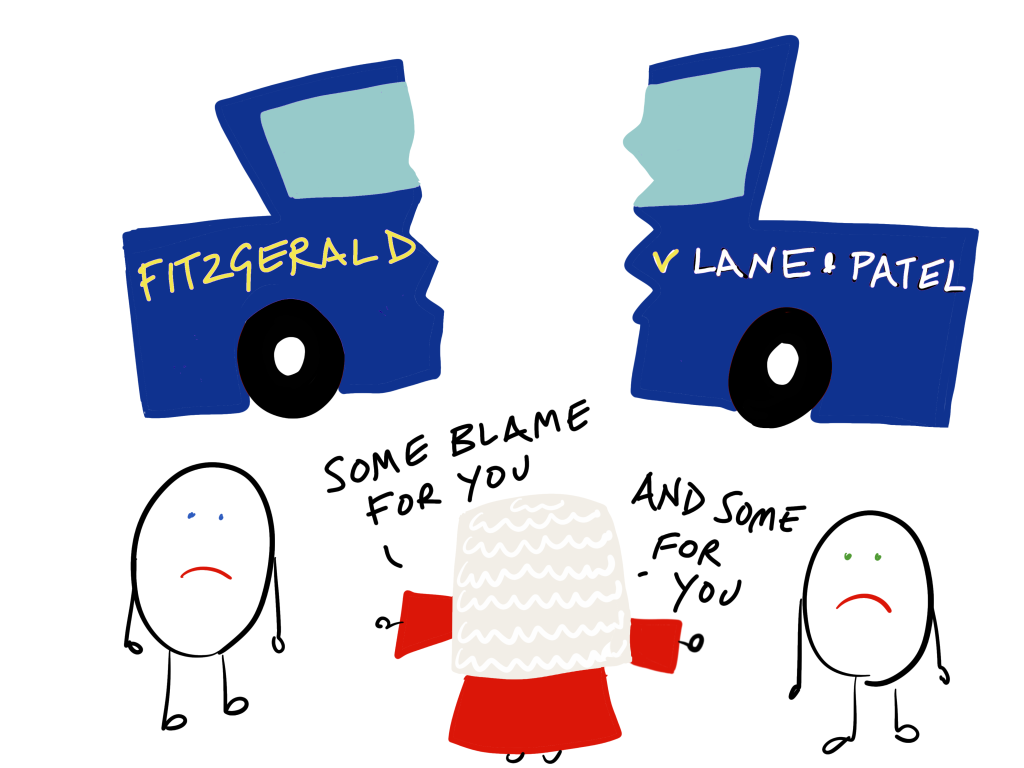

APPORTIONING LIABILITY BETWEEN DEFENDANTS

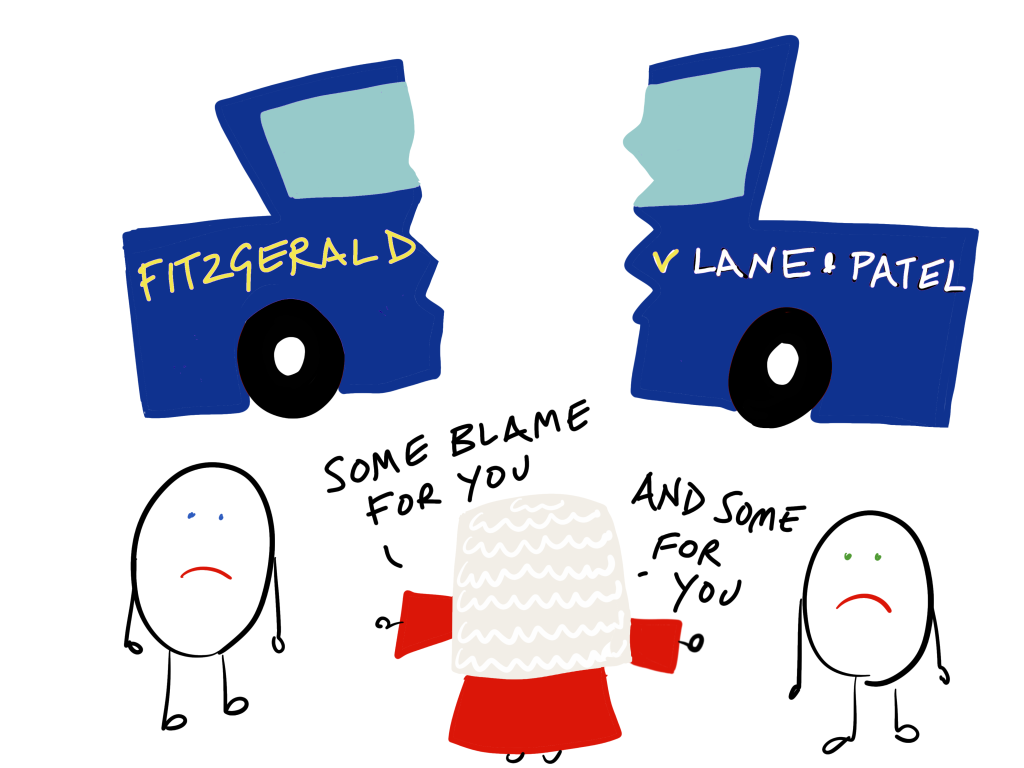

In cases involving several defendants who have been found liable the court can apportion liability between them (Fitzgerald v Lane & Patel (1987) (HoL)).

Fitzgerald, crossing the road, was hit by a car and thrown into the path of another car, which also hit him. He was left tetraplegic. It was impossible to tell which car had caused the injury. If the court held each party 50% liable the ‘but for’ test would mean that neither would pass the 50% threshold and therefore neither would be liable. Instead the court held that both parties were liable based on the material contribution to risk test and liability was apportioned between them. However, on appeal they also found that the claimant had acted negligently by crossing the road when the traffic lights were green and the proportions were adjusted to make Fitzgerald 50% liable and the two drivers 25% each.

FAIRCHILD EXCEPTION

In Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services (2002) (HoL) the House of Lords implemented a specific method for apportioning damages in cases in which the claimant had suffered from mesothelioma and it was impossible to tell which defendant had caused the harm. They found all of the defendants jointly and severally liable. This means that all defendants are jointly liable for 100% of the damages awarded but that they can seek to apportion liability between themselves.

However, in Barker v Corus (2006) (HoL), another case involving mesothelioma, the court employed a strategy more similar to that in Fitzgerald v Lane & Patel (1987) (HoL); each defendant was apportioned a percentage of damages based on how long the claimant had been exposed to asbestos dust whilst working for them. Although potentially more fair for defendants this method was criticised by potential claimants because it meant, for example, that if a defendant had gone bust the claimant would not be able to recover that portion of the damages, whereas under the Fairchild method the claimant would have received full compensation because the other defendants would have to cover the whole sum.

Only three months later Parliament introduced the the Compensation Act 2006. Section 3 sets out that the Fairchild method of apportioning damages must to be used in cases involving mesothelioma. All defendants, if found liable, are to be jointly and severally liable. It is the defendants’ responsibility to apportion damages between themselves or seek compensation from any other party that was not a party to the claim. Any act of the claimant that increased their risk of damage should be addressed as a matter of contributory negligence. In other cases the Barker v Corus (2006) (HoL) method should be followed.

In Zurich Insurance v International Energy Group Limited (2015) (SC) Lords Neuberger and Lord Reed said that the Fairchild exception is ‘applicable to any disease which has the unusual features of mesothelioma’.

MULTIPLE DAMAGE

What happens if multiple, but unconnected, events occur that both cause the same damage or worsen the original damage. Does the second event supersede the first in terms of liability?

SAME DAMAGE

In Performance Cars v Abraham (1962) (CoA) the claimant’s Rolls Royce was damaged in an accident, caused by someone else, after which the car needed a full body respray. Before the work could be done the same car was involved in another incident causing similar damage, also requiring a respray. The court held that as the damage already existed the second collision caused no damage and the second defendant was not liable.

INCREASED DAMAGE

What happens if two different events occur, the second of which increases the damage done by the first? Who will be responsible for what damage? Often the courts will chose a solution that best compensates the claimant without apportioning liability unfairly to the defendant. Compare the two cases below…

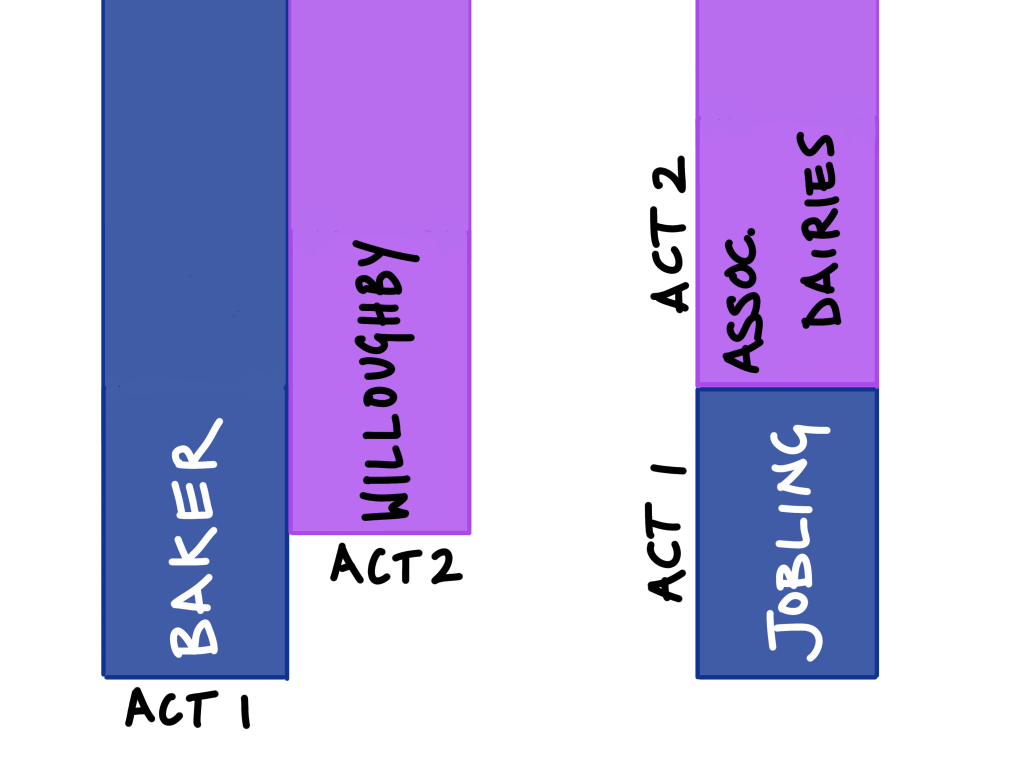

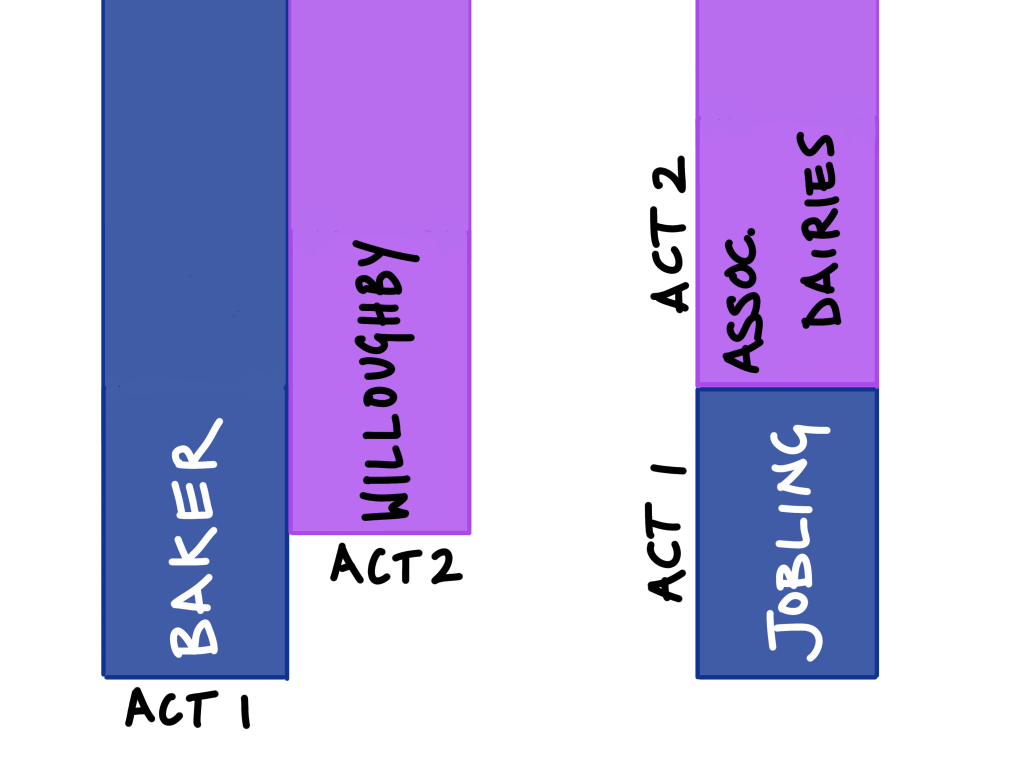

| In Baker v Willoughby (1970) (HoL) the claimant’s leg had been injured in a car accident. Due to his injury he had to find alternative work. He was then shot in the same leg during a robbery at work, this injury meant that the leg had to be amputated. The original tortfeasor argued that his liability ended when the second act occurred because it ‘obliterated’ the effect of his negligence. The court held that if this was the case then there would be a gap in damages; the second tortfeasor (the robber) would be liable for the loss of leg but not the damage caused by the original accident, therefore the claimant would not receive the full compensation he deserved. In addition the claimant would not have been in his new job if it had not been for the negligence of the original defendant. Therefore, the defendant’s liability for pain caused by his negligence continued despite the second negligent act. |

In Jobling v Associated Dairies (1982) (HoL) the claimant injured his back at work leaving him unable to work to full capacity. Subsequently he contracted a back disease (through no act of negligence) that meant he was completely unable to work. The court held that the defendant’s liability ended when the non-tortious back injury occurred because it superseded the original injury. The court argued that it must take into consideration the normal ‘vicissitudes of life’ and the back disease was a hardship that would have occurred anyway so the defendant’s liability should reflect this. |

How can Baker and Jobling be differentiated? In simple terms the difference between the two is that one involved a second act that was tortious and the other a second act that was not. Much will depend on the exact facts of the case and how liability can be apportioned most fairly. For example, one could also argue that in Baker v Willoughby getting compensation from the robber was impossible so the court was avoiding leaving the claimant with nothing.

LEGAL CAUSATION

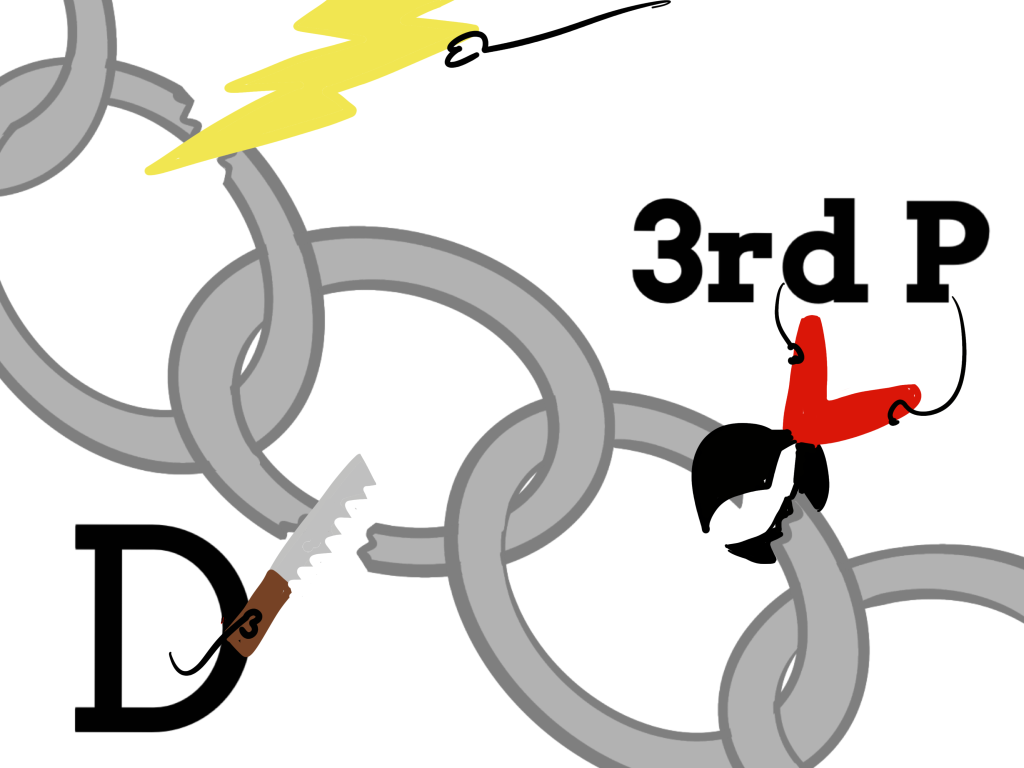

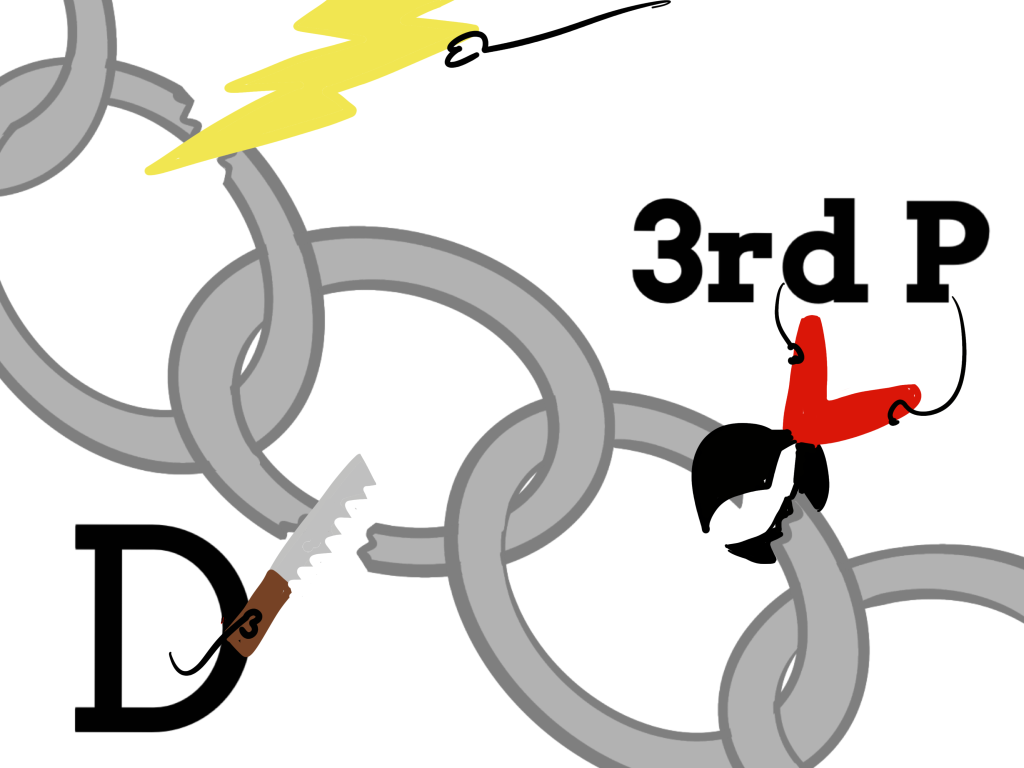

Legal causation looks at whether there are any legal reasons why the breach did not cause the damage. Were there any novus actus interveniens or new intervening acts that broke the chain of causation? There are three categories of intervening act; Act of God or natural events, Act of a third party, Act of the claimant.

ACT OF GOD

Acts of God include natural phenomena such as lightening, floods or storms. As long as the defendant could not have foreseen the event and it is wholly unconnected with their actions then an Act of God will break the chain of causation.

In Humber Oil Terminal Trustees v Sivand (1998) (CoA) the defendants were fixing a harbour when the sea bed collapsed and a boat was damaged. This was technically an Act of God but the defendants were still liable because the collapsing of the sea bed was a foreseeable act and therefore something that the defendant should have taken into consideration.

ACT OF A THIRD PARTY

The act of a third party will break the chain of causation if it was unforeseeable (Knightley v Jones (1982) (CoA)). Negligent driving caused a road traffic accident in a one-way tunnel. When the police arrived they failed to stop traffic coming into the tunnel. The police inspector then ordered two officers to travel the wrong way through the tunnel on motorcycles to stop the traffic. One officer was hit by a car and died. The person whose negligent driving had caused the accident successfully argued that the act of the police inspector, who negligently ordered the officer to travel against the flow of traffic, broke the chain of causation and he was not responsible for the police officer’s death.

More often the courts will apportion liability between the parties, it is quite rare for the act of another person to completely break the chain.

However, if a third party acted in the heat of the moment in response to the negligent act of the defendant then their act will not break the chain (Scott v Shepherd (1773) (HC)). The defendant threw a lit squib into a crowded market place. Before it hit the claimant it was thrown onward by several market traders. The acts of the market traders did not break the chain of causation, Shepherd was still liable for the damage.

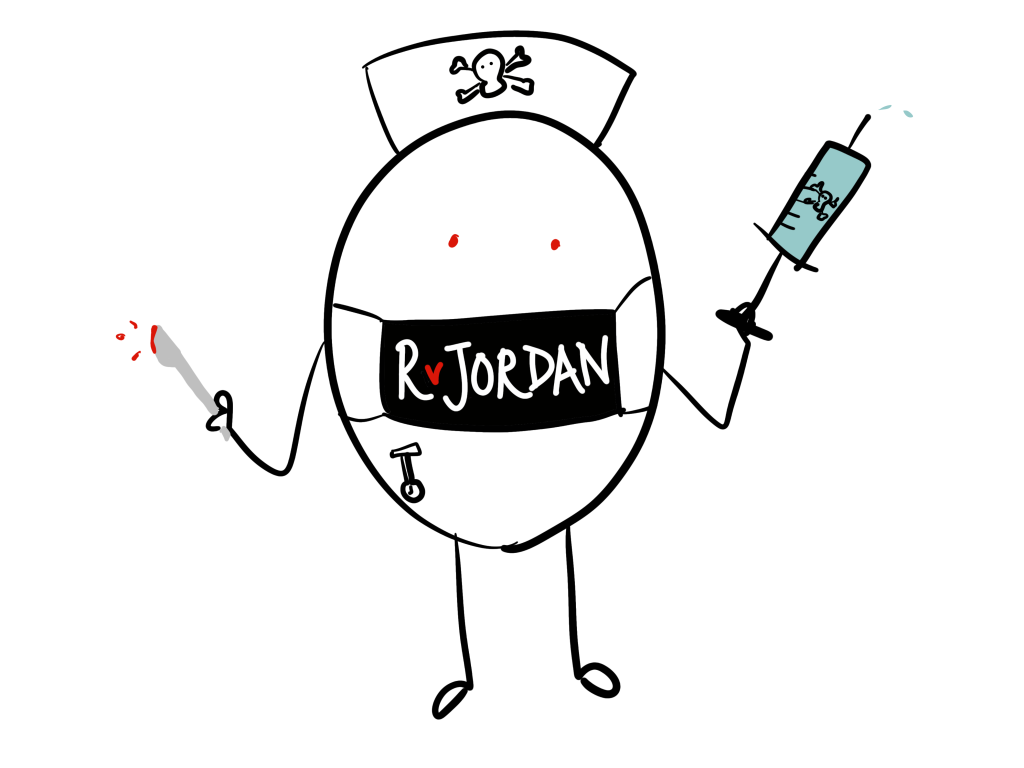

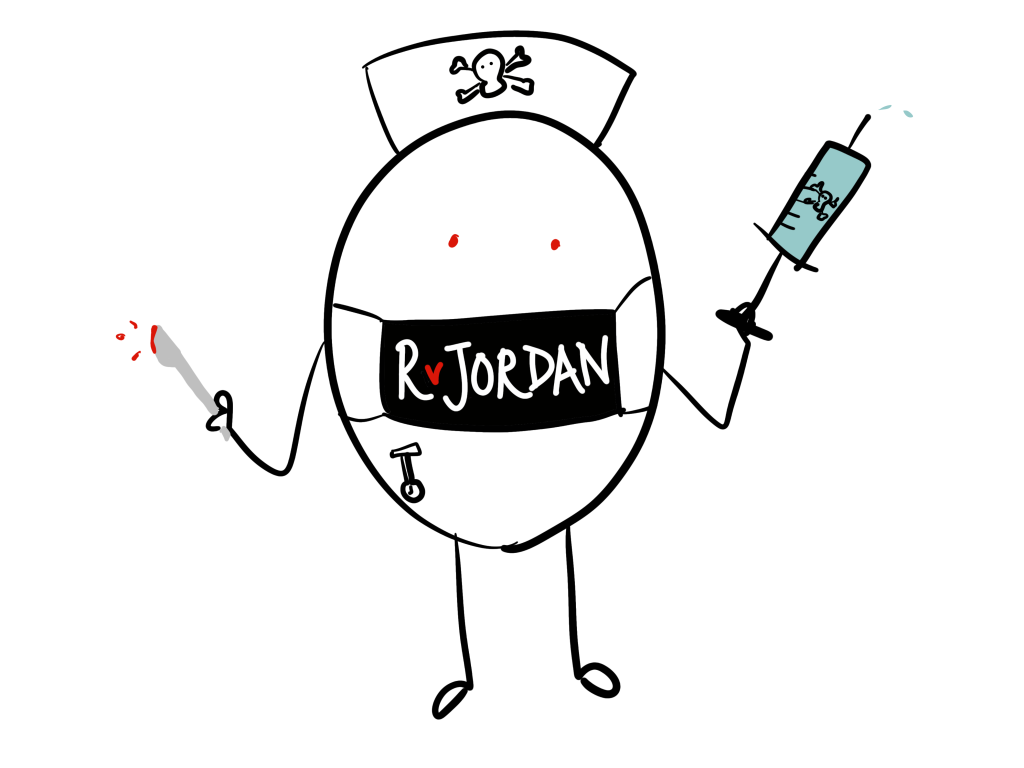

ACT OF MEDICAL NEGLIGENCE

In general, for public policy reasons, an act of medical negligence will not break the chain of causation. The claimant would not have been in hospital if it had not been for the negligent act of the defendant so they are still held liable for anything that goes wrong in hospital. Medical negligence will only break the chain if it is ‘palpably wrong’ (R v Jordan (1956) (CoA)).

The victim was hospitalised after being stabbed by the defendant. Whilst in hospital he was given an excessive amount of intravenous liquids and a drug to which he was known to be allergic. . These acts of medical negligence led to him contracting pneumonia from which he died. They were deemed to be ‘palpably wrong’, breaking the defendant’s chain of causation.

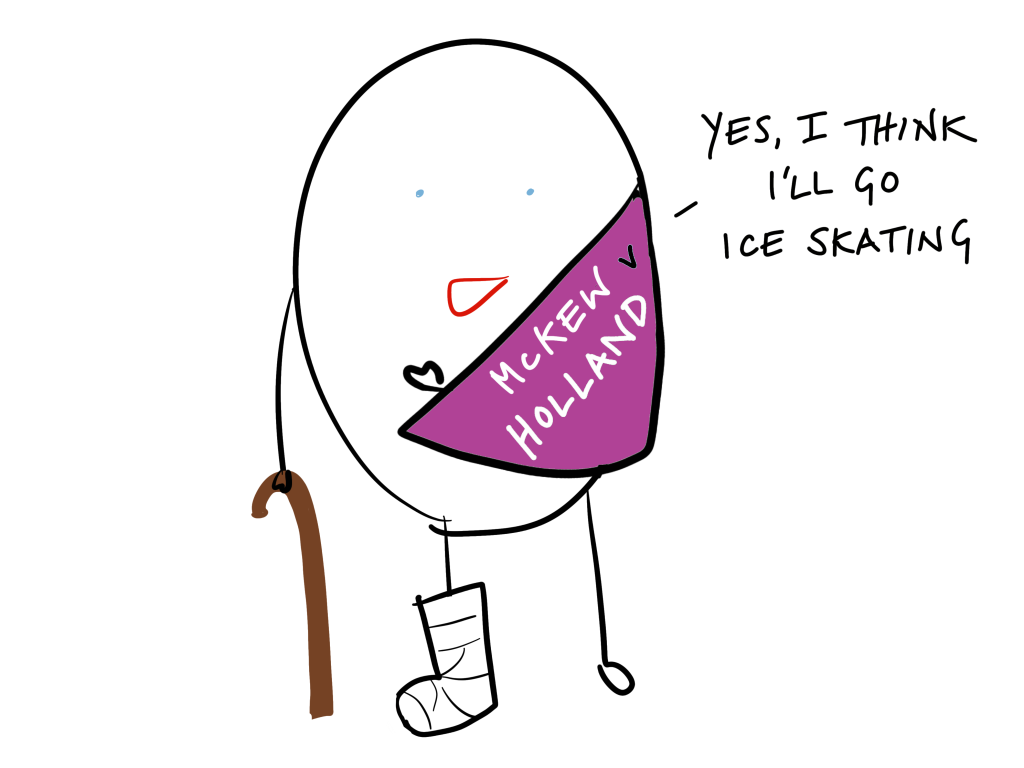

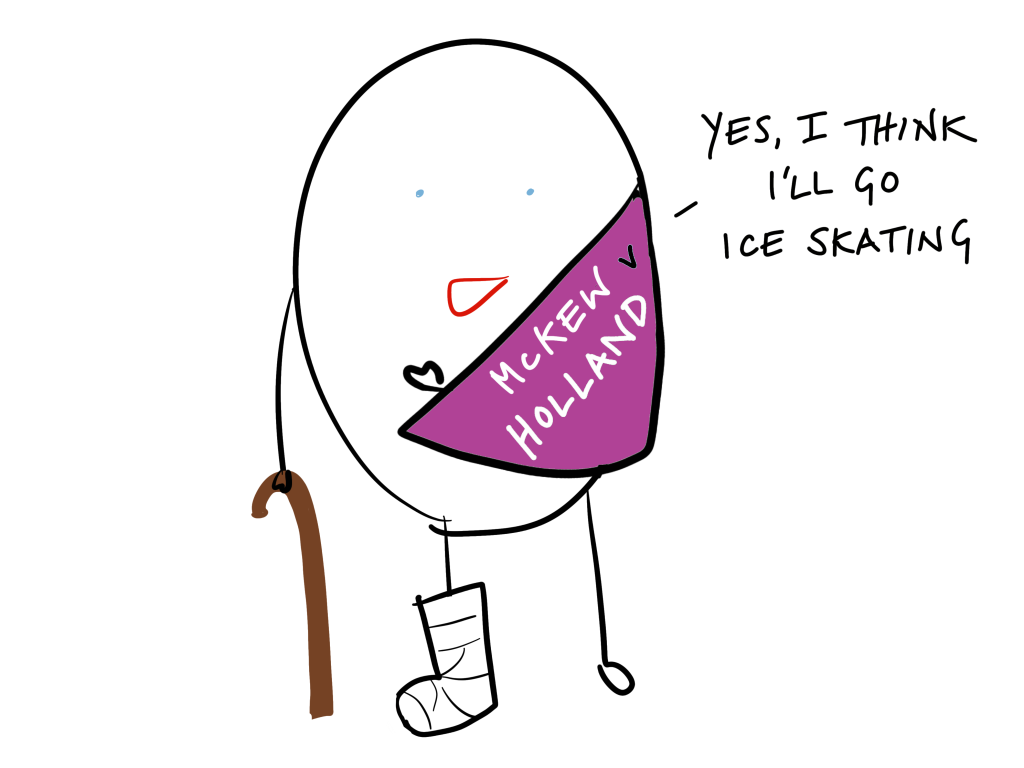

ACT OF THE CLAIMANT

An unforeseeable, and generally unreasonable, act of the claimant can break the chain of causation (McKew v Holland and Harman and Cubitts (1969) (HoL)).

McKew’s leg had been injured due to a negligent act of his employer. Whilst he was recovering he went to inspect a flat for work and had to descend a steep flight of stairs with no hand rail. Nearing the bottom he felt his injured leg give way so decided to jump to the bottom where he further injured himself. This was deemed an unforeseeable and unreasonable act by the claimant that broke the chain. The defendant was not liable for any injury caused by that action.

Compare this to Wieland v Cyril Lord Carpets (1969) (HC) in which a woman who had been injured by the defendant’s negligence had to wear a neck brace. This meant that she could not wear her glasses. Due to her impaired vision she fell down some stairs and injured her ankle. The court held that there was no break in the chain; the claimant had been as careful as could be expected (her son was with her when she tried to go down the stairs) and her actions were not unforeseeable or unreasonable.

In the more modern case of Spencer v Wincanton Holdings (2009) (CoA) the court relied upon Lord Bingham’s obiter dicta from Corr v IBC Vehicles (2008) (HoL) (see below) basing their decision on fairness rather than the unreasonableness of the claimant’s action. They asked themselves; when was it fair to release the defendant from liability because of the actions of the claimant? In this case Spencer had been injured at work which had led to his leg being amputated. One day at the petrol station he got out of his car without his prosthetic leg or crutches and tripped over a man-hole cover resulting in another injury which left him in a wheelchair. The court held that his action had not broken the chain of causation because it would not be fair to end the defendant’s liability.

SUICIDE

Suicide will not break the chain of causation. In Kirkham v Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police (1990) (CoA) and Reeves v Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis (2000) (HoL) the police were found to have a specific duty to the claimant to prevent them from committing suicide. The claimant’s actions were therefore foreseeable and would not break the chain of causation.

In Corr v IBC Vehicles (2008) (HoL) the claimant had suffered an injury at work that led to clinical depression and suicide. Although the defendants in this case did not owe the claimant a specific duty of care to prevent suicide the court held that the suicide was not a voluntary action but had been brought about by the psychological damage that the negligent act had caused and therefore did not break the chain.

CRIMINAL ACTS

In Gray v Thames Trains (2009) (HoL) the claimant suffered PTSD after being involved in the Ladbroke Grove train crash. He later went on to stab someone to death but was convicted of manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility. Gray sued the company responsible for the train crash for such things as loss of earning during his time in detention. The claim was unsuccessful as the court held that Gray’s later criminal acts broke the chain of causation.

Acts of the claimant that do not completely break the chain might instead reduce the damages based on the defendant’s contributory negligence. For example, in Spencer v Wincanton Holdings (2009) (CoA) (see above) the claimant’s damages were reduced by one third to reflect the contribution of his actions to the harm suffered.