JUMP TO: CONSENT | CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE | ILLEGALITY | REVISE | TEST

DEFENCES

There are a number of defences available to the defendant and the burden of proof in establishing a defence will rest with the defendant, on the balance of probabilities.

CONSENT

The defendant will have a complete defence if they can prove that the claimant consented to the risk. Otherwise known as volenti non fit injuria – that to which a man consents cannot be considered an injury.

The claimant must have known of the risk and its extent and have voluntarily agreed to the injury.

KNOWLEDGE

This is a subjective not an objective question; did that particular claimant know of the risk?

In Morris v Murray (1991) (CoA) both claimant and defendant were drunk when the claimant agreed to be flown in a plane by the defendant. The plane crashed killing the pilot and injuring the claimant. Whether the claimant’s state of inebriation had affected his ability to appreciate the danger had to be taken into account. He was affected by the alcohol but not to such an extent that he would not have known and understood the great risk involved in being flown by a drunk pilot. He was found to have consented to the risk.

VOLUNTARILY AGREED

It is not enough that the claimant was aware of the risk, they must have voluntarily agreed to it.

Compare the case of Morris v Murray (1991) (CoA), above, with Dann v Hamilton (1939) (HC) in which the claimant accepted a lift in a car knowing that the driver was drunk. However, this was not considered the type of extreme case in which the defence could be used and the claimant was not found to have consented to the risk. As there was only a mere risk that the driver’s drunk state would lead to any injury her action of getting in the car was not enough to prove consent. Complete knowledge of a risk does not necessarily mean that the claimant consented to the risk and waived the defendant’s liability. Asquith J stated that consent may be found if ‘to accept a lift from him [a drunk driver] is like engaging in an intrinsically and obviously dangerous occupation, intermeddling with an unexploded bomb or walking on the edge of an unfenced cliff’.

So what is the difference between the two? The action of agreeing to be flown in a plane by a drunk pilot could be compared to ‘intermeddling with an unexploded bomb’, a decision more dangerous than being driven in a car by a drunk driver.

Cases involving car accidents are now covered by s.149 Road Traffic Accident 1988 which stops negligent drivers from using the defence of volenti against passengers.

GIVING CONSENT

Consent can be given expressly or impliedly (Hall v Brooklands Auto Racing Club (1933) (CoA)).

Spectators were killed whilst watching a motor race when two racing cars collided and crashed into the spectators. The spectators were deemed to have impliedly and voluntarily agreed to the risk. A motor crash was an inherent risk of the sport and choosing to stand by the race track carried with it the risk of being involved.

EMPLOYEES

An employee will not necessarily have automatically agreed to a risk just because they have knowledge of it. Employees may feel unable to avoid the risk in order to keep their jobs (Smith v Charles Baker & Sons (1891) (HoL)).

The claimant was working on building a railway when a crane dropped a rock on him. Previously the claimant and his colleague had complained about the risk of rocks being carried above their heads. He was aware of the risk and continued to work despite this but that did not mean that he had voluntarily consented to it because as an employee it was difficult for him to avoid the risk.

It will be difficult for an employer to prove consent unless the employee acts expressly against the employer’s instructions (ICI v Shatwell (1965)) (HoL).

The claimants had injured themselves using fuses that were too short when setting off explosives in a quarry. The employer was not liable for the harm caused as the injured parties had acted contrary to their express instructions.

MENTAL CAPACITY

In order to give valid consent the claimant must have the mental capacity to do so. In both Kirkham v Chief Constable of Greater Manchester (1990) (CoA) and Reeves v Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis (1999) (HoL) the police tried to use the defence of volenti non fit iniuria against claimants who had committed suicide in police custody. They failed because neither claimant, being suicidal, had the mental capacity to consent to their own suicide.

RESCUERS

Someone acting as a rescuer will not have given their consent to the risk. In Haynes v Harwood (1935) (CoA) Harwood had left his horse untethered on the street. Whilst left unattended children threw stones at it and the horse bolted. Haynes, a policeman, was injured trying to catch the horse. Haynes had not consented to this risk because he was acting for the benefit of others to avert a danger.

Compare to Cutler v United Dairies (1933) (CoA). Cutler was also injured trying to catch a runaway horse. However, by the time Cutler had caught the horse, and it had injured him, the horse had come to a standstill in the middle of a field and posed no immediate danger to anyone. Therefore he was not considered a ‘rescuer’ by the law and had consented to the risk.

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE

Contributory negligence is not a complete defence but it will go towards reducing a defendant’s liability. It is governed by s.1 Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945. If the claimant was partly at fault the defendant’s liability can be reduced to a level that the court considers to be just and equitable.

The claimant must have contributed to the risk of injury not necessarily the risk of accident. Although if a claimant also contributed to the risk of the accident this can be reflected in the apportionment of a greater level of liability. The claimant will only have contributed to the type of injury that might be a consequence of their action, for example not wearing a crash helmet would contribute to a head injury but not a broken leg.

Contributory negligence is not available for assault or battery as they are intentional torts.

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE – FAULT

Fault is defined by s.4 of the Act as ‘negligence, breach of statutory duty or other act or omission which gives rise to liability in tort’.

The claimant must have been acting unreasonably. This is the same objective test used to assess whether the defendant has breached their duty of care. The risk posed by the carelessness of others will also be taken into consideration (Jones v Livox Quarries (1952) (CoA)).

Jones had put himself in a dangerous position by riding on the tow bar of a work vehicle. When the vehicle was involved in an accident caused by another vehicle he was injured. He had contributed to his injury by riding the tow bar and not considering the potential risk of an accident caused by the carelessness of another.

In Froom v Butcher (1976) (CoA) the fact that the claimant had not been wearing their seatbelt when involved in a car accident was deemed unreasonable, even though wearing a seatbelt was not legally compulsory. Compare to Stanton v Collinson (2010) (CoA) in which not wearing a seatbelt was not deemed to have contributed to the injury sustained in a car accident because it was shown that even if the claimant had been wearing a seat belt they would still have suffered the same injury.

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE – HEAT OF THE MOMENT

If a claimant was acting in the heat of the moment, for example as a rescuer or reacting to a dangerous situation, then their action will not be seen as contributory (Jones v Boyce (1816) (HC)).

A man jumped from a runaway carriage. This was not seen as his fault as it had happened in the heat of the moment and he had therefore not contributed to his injury.

This will not be the case if the person had contributed to the creation of the risk. In Harrison v British Rail Board (1981) a train guard tried to help a passenger jump onto the train as it was leaving the station. The guard signalled the driver for the train to slow down but by accident gave the signal to accelerate. He then tried to pull the passenger on board but they both fell out of the train. The guard sued the passenger for putting him in a dangerous situation by trying to jump on a moving train. The court held the passenger liable but reduced the guard’s damages by 20% to reflect his contribution to the injury. However, they also stated that subjecting a rescuer to contributory negligence is ‘rarely appropriate’.

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE – CHILDREN

In general children cannot be guilty of contributory negligence. However, his may not be true for older children who might be expected to take more responsibility for their actions (Gough v Thorne (1966) (CoA)). A 13 year old was struck whilst crossing the road. A lorry had stopped and waved the children over but another car drove around the lorry and hit the girl. At first instance the court found that the girl had contributed to her injury by not checking the road before passing the lorry. However, the Court of Appeal reversed the judgment. As she had been waved across by the lorry her lack of checking the road had not been unreasonable.

ILLEGALITY

Ex turpi causa non oritur actio – no action may be based on an illegal cause.

This is a complete defence that aims to stop a claimant from being compensated if their own illegal activity led to or contributed to the damage suffered by them (Ashton v Turner (1981) (HC)).

Ashton was injured in a car accident but as the car was a getaway vehicle and both passenger and driver had just committed a robbery he was unable to recover any damages from the defendant.

In Vellino v Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police (2002) (CoA) Vellino injured himself jumping out of a window trying to escape arrest. He sued the police, claiming that they owed him a duty of care after being arrested to stop him injuring himself. The court disagreed, he had committed an act that was illegal and clearly dangerous, the police owed him no duty of care once he tried to escape.

EXCEPTION TO DEFENCE OF ILLEGALITY

In rare situations a claimant who was committing an illegal act will be able to recover (Revill v Newbury (1996) (CoA)). Newbury, worried about theft from his allotment shed, decided to sleep in his shed with a loaded shot gun. When Revill tried to burgle the shed Newbury fired the gun through a hole in the door intending to scare him away but Revill was injured. Even though Revill had been committing a crime the court held that Newbury’s actions had been out of proportion to the perceived threat and would not allow the complete defence of ex turpi causa. Instead they found Newbury liable but reduced damages by two thirds to reflect his liability.

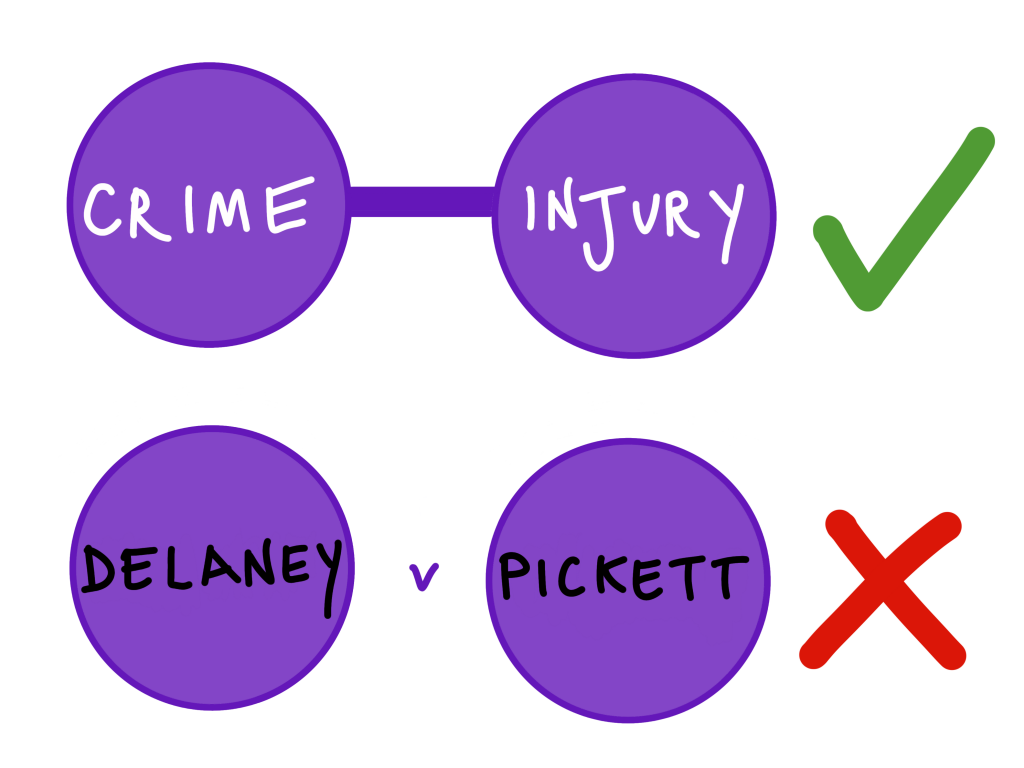

UNCONNECTED ILLEGAL ACTIVITY

If the illegal action is unrelated to the incident then the defence will not apply (Delaney v Pickett (2011) (CoA)).

A passenger who was injured in a car accident caused by the defendant’s negligent driving could still recover damages even though they were carrying large amounts of cannabis. Although illegal it was not related to the negligent act so the defendant could not use illegality as a defence.