JUMP TO: LIBEL | SLANDER | WHO CAN SUE? | DEFAMATORY STATEMENT | SERIOUS HARM | INNUENDO | CONTEXT | REFERS TO CLAIMANT | PUBLICATION | DEFENCES | REMEDIES | REVISE | TEST

DEFAMATION

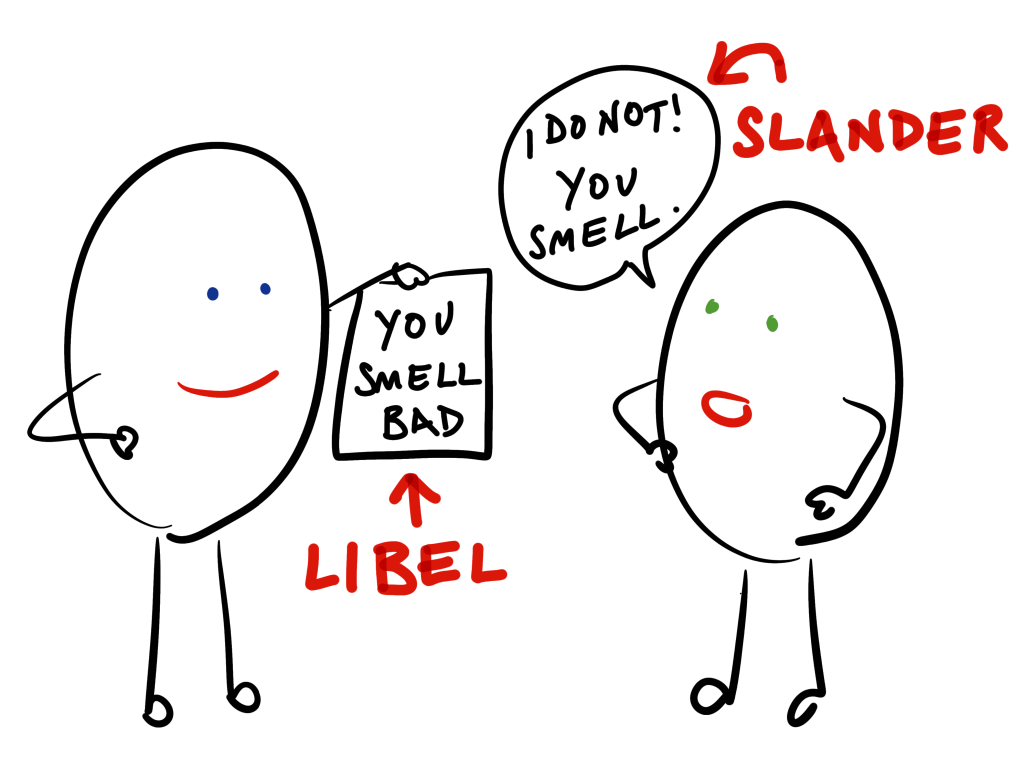

Defamation occurs when an untrue statement is made that harms the reputation of another. Defamation comprises both libel and slander.

Bear in mind that this area of law is now covered by the Defamation Act 2013 making older case law instructive rather than binding. Defamation cases can still be heard by a jury however since the Defamation Act 2013 this is no longer a presumption and must be ordered by the judge. The judge will decide whether a statement is capable of being defamatory. If it is then the case will go before a jury who will decide whether the statement was in fact defamatory.

LIBEL

Libel is defamatory statements that are published in a permanent form. The most obvious being in writing but any sufficiently permanent form will suffice.

In Monson v Madame Tussauds (1894) (CoA) a waxwork was considered a form of libellous statement. Statues, caricatures, effigies, chalk marks on a wall, signs and pictures were also listed as permanent statements. In Youssoupoff v MGM (1934) (CoA) a film that alleged that the claimant had been raped by Rasputin was a statement capable of being libellous.

PUBLISHED ON THE INTERNET

Anything published on the internet is deemed permanent for the purposes of libel (Godfrey v Demon Internet (1999) (HC)) even on social networking sites that have restricted access (Applause Stores Productions v Raphael (2008) (HC)).

SPOKEN WORDS

However, spoken words that have been recorded are usually slander rather than libel. The exception to this being recordings for television or radio as covered by the Broadcasting Act 1990 or public theatre under the Theatres Act 1968.

ACTIONABLE PER SE?

In theory libel is actionable per se, i.e. the claimant need not show that the statement caused actual loss or damage. However, under the Defamation Act 2013 s.1(1) the claimant must show that the statement ‘caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the claimant.’ Therefore there is now a requirement for the claimant to prove that the statement could cause them serious harm, even if they have no proof of actual damage. This is designed to discourage frivolous claims.

SLANDER

Slander is a defamatory statement made in a temporary or transitory form. Usually spoken word but could also be mimicry, gesture or sound.

A claimant must show that the slander caused material damage – such as loss of earnings – in order to bring a case. The only exceptions to this are if the statement held that the claimant had performed a criminal act (Webb v Beavan (1883) (HC)) or that they were incompetent in business dealings (McManus v Beckham (2002) (CoA)). These statements are damaging in themselves so no proof of further damage is required.

WHO CAN SUE?

Only a living person can sue for defamation, cases cannot be brought involving statements made about the dead. If a claimant dies before a case is determined the case will end.

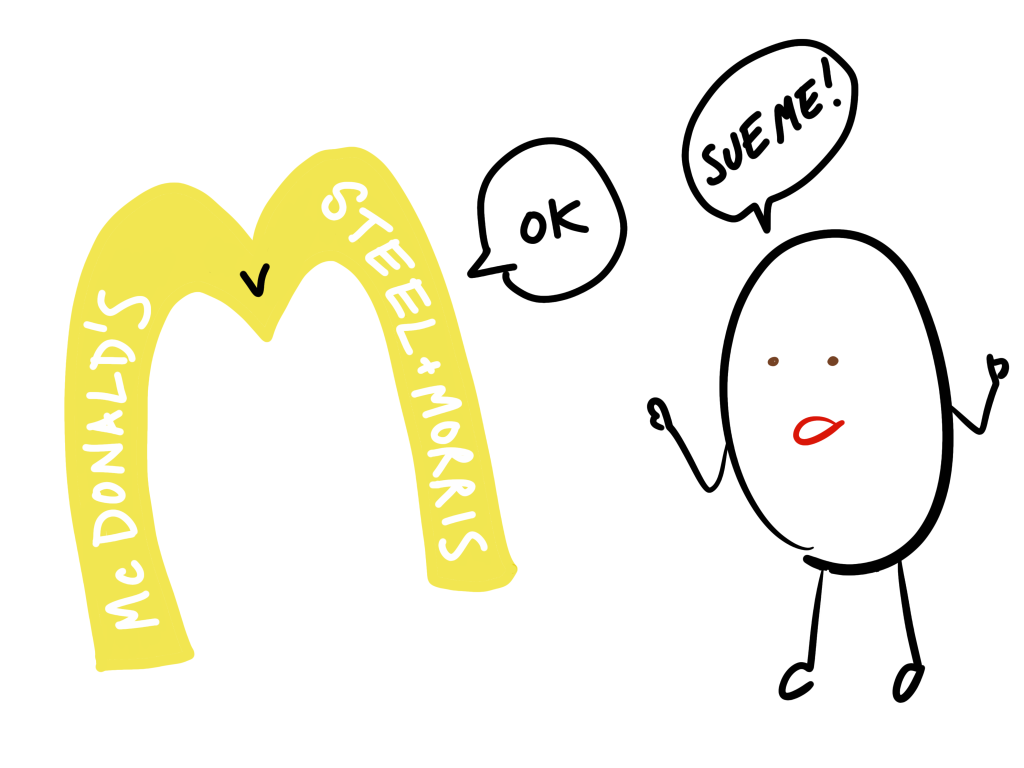

Companies (or ‘bodies that trade for profit’) can sue for defamation. This was confirmed in McDonald’s v Steel & Morris (1995) (CoA), a case that became known as the McLibel Case.

It ran for 10 years making it probably the longest running libel case in English legal history. Steel and Morris were environmental activists who had published a pamphlet called ‘What’s Wrong with McDonald’s?’. The court found that only some of the statements made in the pamphlet were libellous and awarded McDonalds £20,000.

EXCEPTIONS

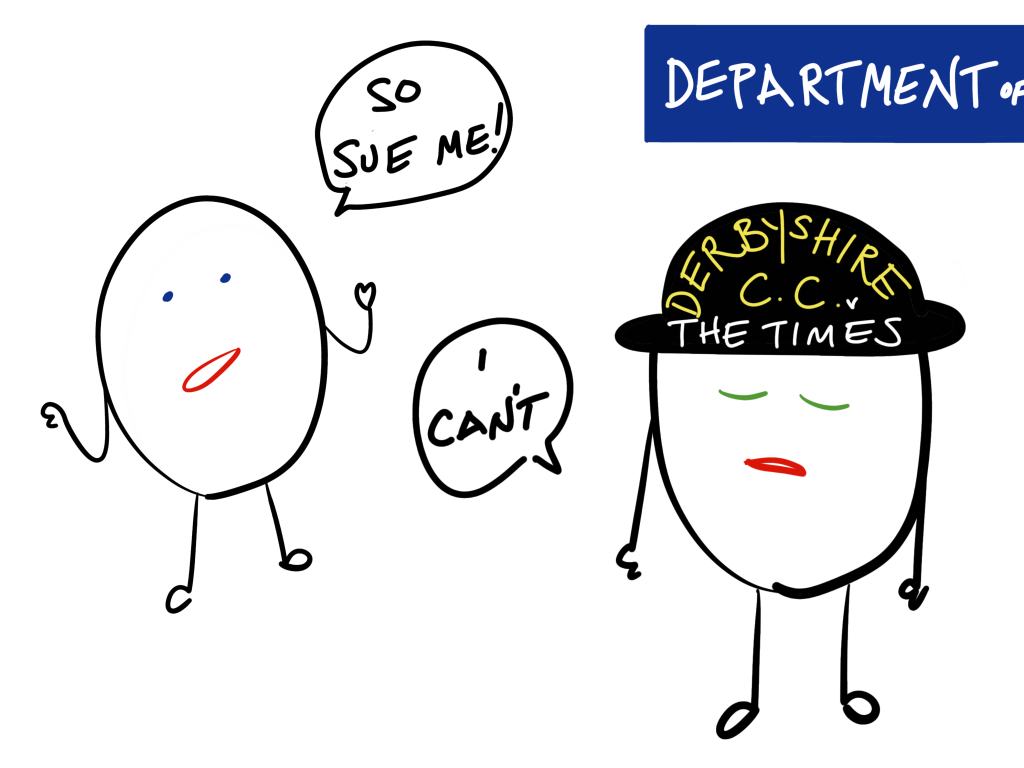

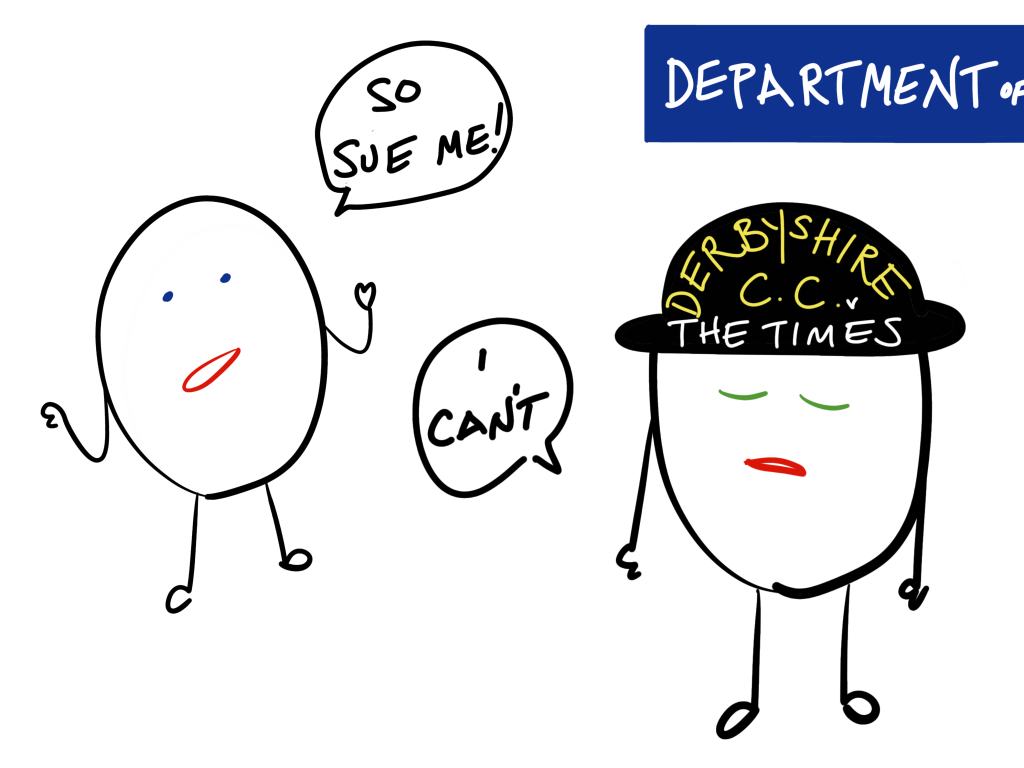

The only type of party barred from bringing a case is governmental organisations (Derbyshire County Council v Times Newspapers (1993) (HoL)).

The Times had published several stories that claimed financial mismanagement at the Council. The court held that the Council could not sue for defamation because the freedom to publicly criticise political organisations outweighed their right to not be defamed.

This exception was extended to political parties in Goldsmith v Bhoyrul (1997) (HC) a case involving claims made against James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party. However, individual politicians can bring defamation cases.

Section 9(2) of the Defamation Act 2013 restricts so called libel tourism. A party can only bring a defamation case in England & Wales if that jurisdiction is the most appropriate location.

DEFAMATION

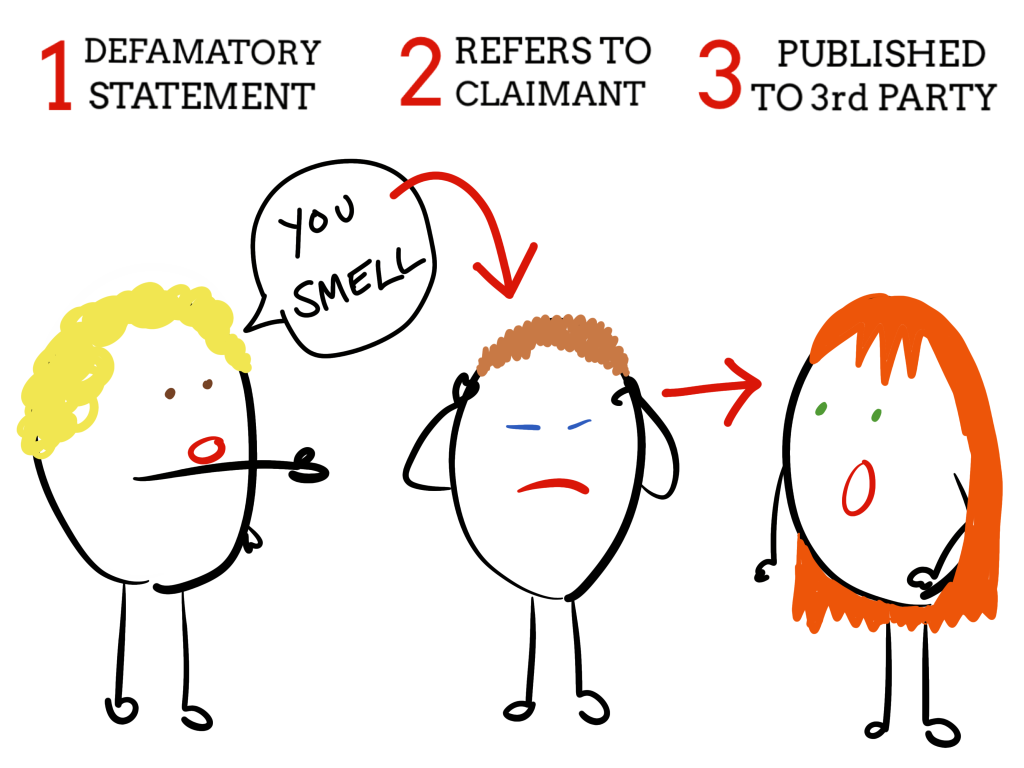

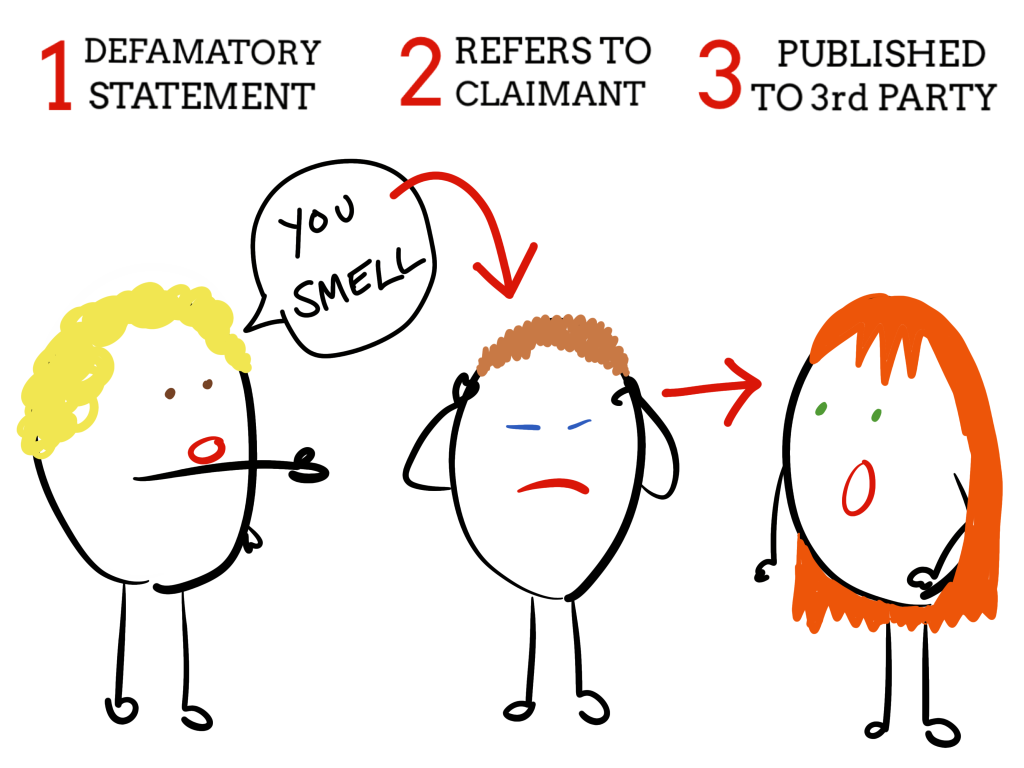

A claim for defamation must consist of the following elements.

MAKING A DEFAMATORY STATEMENT

WAS THE STATEMENT DEFAMATORY?

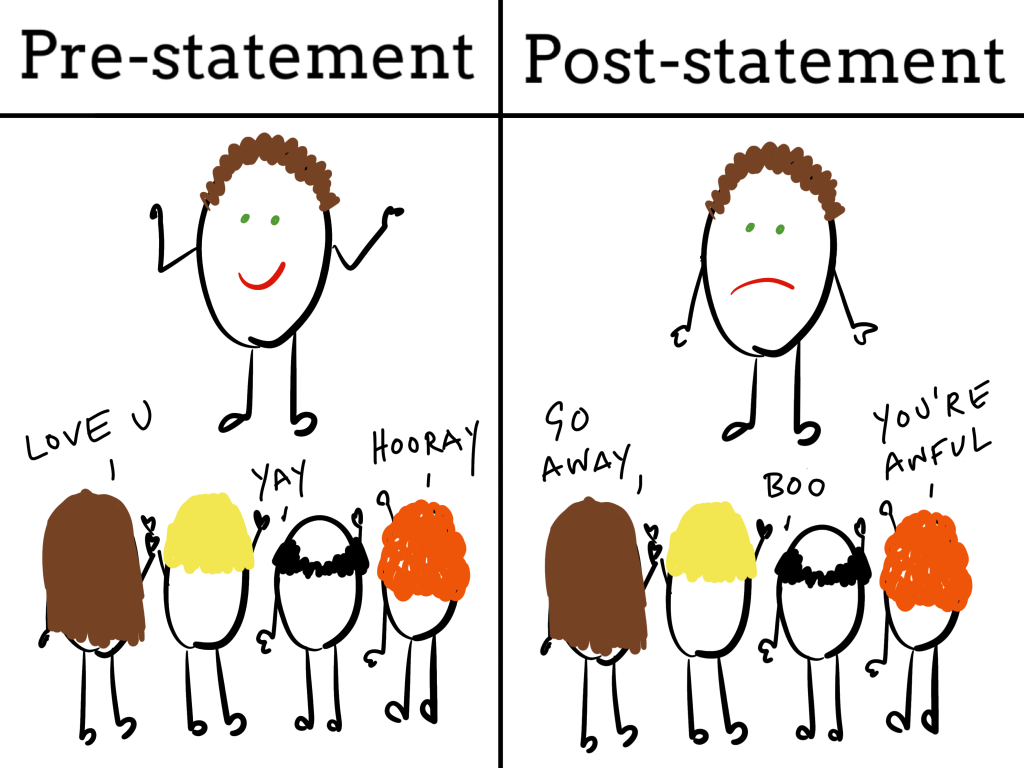

A defamatory statement was defined as; ‘A statement which tends to lower the claimant in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally, and in particular to cause him to be regarded with feelings of hatred, contempt, ridicule, fear and disesteem’, Lord Atkin in Sim v Stretch (1936) (HoL).

The definition of ‘right-thinking members of society’ was extended by Lord Reid in Lewis v Daily Telegraph (1964) (HoL). ‘The ordinary, reasonable reader is not naïve; he can read between the lines. But he is not unduly suspicious. He is not avid for scandal. He would not select one bad meaning where other, non-defamatory meanings are available’. Whether a statement had a defamatory meaning will be judged according to this objective standard.

What is defamatory will change with the times. For example, in Youssoupoff v MGM (1934) (CoA) the claimant, a member of the Russian Royal family, argued that the statement made in a film that she had been raped by Rasputin would lead people to shun her, a statement that might not be deemed defamatory today.

REPUTATION

The meaning of reputation is to be construed widely as relating to ‘all aspects of a person’s standing’ (Berkoff v Burchill (1996) (CoA)). Burchill, a well known journalist, described the actor Berkoff as ‘notoriously hideous-looking’ and as ‘only marginally better-looking than the creature in Frankenstein’. When Berkoff sued, the defendant argued that these comments only caused hurt feelings or annoyance and were not damaging to his reputation. This was rejected by the court. The court held that saying someone was hideously ugly could be considered a defamatory statement, taking into consideration his reputation as an actor.

Millett LJ in his dissenting judgment emphasised the difference between ridiculing someone and exposing them to ridicule, in his opinion Burchill had done the former.

In Williams v Mirror Group Newspapers (2009) (HC) the claimant, who was in jail for murder and armed robbery sued the Daily Mirror for stating that he was a grass. The court held that it was impossible for him to be defamed because he had no reputation left to defame.

SPECIFIC REPUTATION

A statement will be defamatory if it would cause serious harm to the specific reputation of the claimant even if it would not do so to another. For example, someone who has built a reputation as a vegan chef could be defamed by an article that claimed they ate meat even though most people would not generally think badly of someone for eating meat.

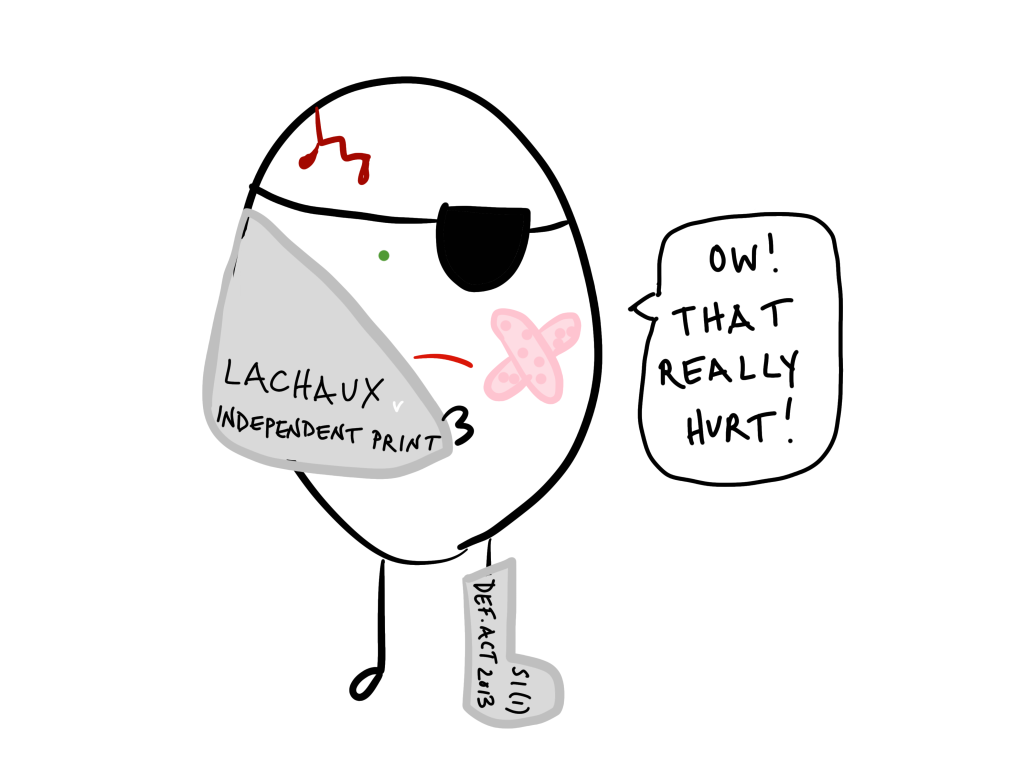

SERIOUS HARM

Before the Defamation Act 2013, for a libel actionable per se, it was only necessary for a claimant to prove that the statement was defamatory they did not have to show that any actual damage to their reputation had occurred. However, under the Defamation Act 2013 s.1(1) the claimant must show, for libels actionable per se, that on the balance of probabilities the statement ‘caused or is likely to cause serious harm to the reputation of the claimant.’

Before being enshrined in legislation case law was already moving towards this requirement. In Jameel v Dow Jones (2005) (CoA) it was stated that the claimant must show that they suffered a ‘real and substantial’ tort and Tugendhat J in Thornton v Telegraph Media Group (2010) (HC) held that the words complained of must pass a ‘threshold of seriousness, so as to exclude trivial claims’ and ‘may be defamatory of him because it substantially affects in an adverse manner the attitude of other people towards him, or has a tendency so to do’. Note, however, that the statutory requirement of ‘serious harm’ is a higher threshold than the ‘substantially affects’ set out in Thornton.

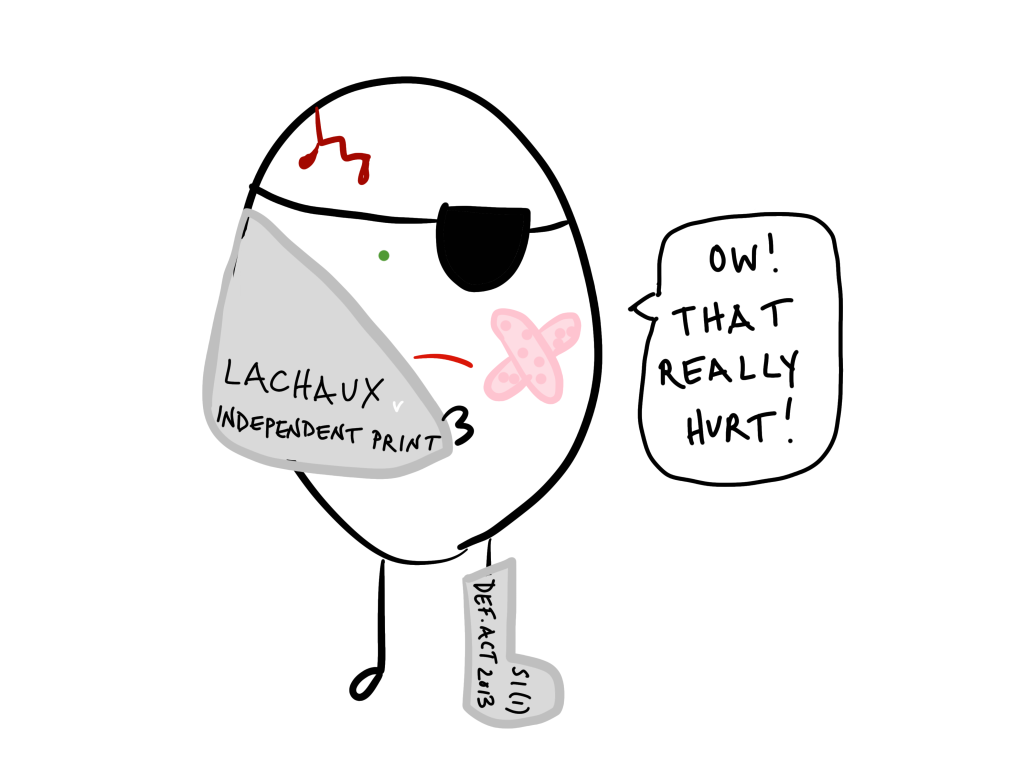

SERIOUS HARM vs ACTIONABLE PER SE

The conflict of being actionable per se and the statutory requirement of serious harm was discussed in the case of Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd (2017) (SC) which clarified how the statute should be implemented and how it fitted in with existing case law.

Lachaux had been involved in legal proceedings in the UAE against his ex-wife for allegedly kidnapping their son. When the story was published by three British newspapers (in four to five articles) the articles included allegations made by the ex-wife that she had been physically abused by Lachaux. Lachaux sued the newspapers. The judge held that the articles had, or were likely to cause, serious harm to the client’s reputation based on the scale of the publications, the fact that the statements had come to the attention of at least one identifiable person in the United Kingdom who knew Mr Lachaux and that they were likely to have come to the attention of others who either knew him or would come to know him in future; and the gravity of the statements themselves. The judge held that serious harm can be inferred from the facts of the case (as evidence of actual damage can be hard to obtain).

The Supreme Court agreed with the judge at first instance that the Act did impose a new requirement that a libel not only be defamatory in the meaning of the words but that the effect of those words caused, or was likely to cause, serious harm based on the actual facts of the case. Whether libel can still be truly actionable per se is therefore questionable.

EXAMPLES OF SERIOUS HARM

Below are a couple of examples of post-Lachaux cases which give helpful examples of how the courts approach a finding of serious harm.

In ZC v Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust (2019) (HC) the claimant was unable to establish serious harm caused by a statement claiming that she was dishonest and fraudulent. Knowles J concluded: ‘In summary, the evidence shows that the number of publishees was very limited; that there was no grapevine percolation; that two of the four publishees knew about the contents of the email in any event before receiving it; and thus that there was no evidence that anyone thought less of the Claimant by reason of the publication of the email’. *The defendant also successfully used the defence of truth as the claimant was found to have lied.

In Fentiman v Marsh (2019) (HC), the defendant had published three separate statements on blogs that the claimant (CEO of a company) had carried out a cyber-attack, was a hacker and that criminal charges were being brought against him. The judge held that the allegations were ‘all grave, and had an inherent tendency to cause serious harm’. Evidence given to prove serious harm was the number of people who had read the blog (between 100 – 230 persons or views for each post), there had been grapevine dissemination and evidence that staff members of the claimant had been worried that the claims were true.

COMPANIES

Harm to the reputation of a body that trades for profit, i.e. a company, will not be serious harm ‘unless it has caused or is likely to cause the body serious financial loss’ (Defamation Act 2013 s.1(2)).

MEANING OF THE STATEMENT

A statement can be defamatory based on its ordinary and natural meaning, or innuendo. In both cases the intention of the publisher is irrelevant. If the recipients of the statement inferred a defamatory meaning from the statement, even if this was not the intention of the publisher, it can still be defamatory.

The difference between the two will affect what damages the claimant might receive; a statement defamatory on its ordinary and natural meaning rather than innuendo will have been understood by more people and have been more damaging, therefore the claimant will probably receive more in damages.

INNUENDO

Innuendo can be either true/legal innuendo or false/popular innuendo.

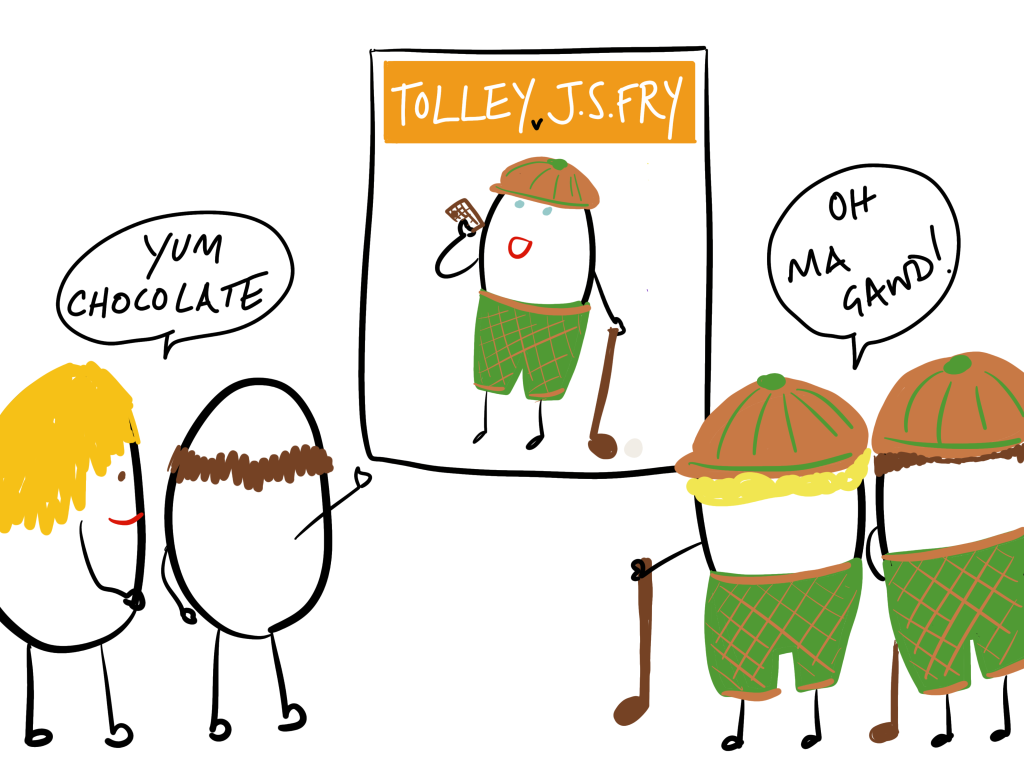

TRUE/LEGAL INNUENDO

True or legal innuendo is when the true meaning of a statement will only be understood by people with knowledge of extrinsic facts. The claimant must prove on the balance of probabilities that someone within the general audience had knowledge of the extrinsic facts necessary to understand the innuendo.

In Tolley v JS Fry (1931) (HoL) a cartoon of the claimant, a famous amateur golfer, was used without permission by the defendant to advertise Fry’s chocolate. The claimant sued for defamation. The use of his image suggested that he had accepted payment to advertise the chocolate which would jeopardise his status as an amateur golfer. Only people within the amateur golfing world would have known this but within that group the meaning of the innuendo would have been very damaging. The statement was found to be defamatory.

The more modern case of McAlpine v Bercow (2013) (HC) is also a good example. BBC Newsnight stated that a senior Tory politician of the Thatcher years had been accused of historic child sex abuse. There was a lot of speculation about who this person was. Afterwards Sally Bercow tweeted ‘Why is Lord McAlpine trending? *innocent face*’. When the accusations were found to be false McAlpine sued Bercow for defamation. The judge found that both its ordinary and natural meaning and the innuendo was that McAlpine was a paedophile and guilty of child sex abuse. Bercow argued that she was merely asking for information but this was rejected. The use of the phrase ‘*innocent face*’ in fact signified the opposite, that there was something guilty about McAlpine. It was reasonable to assume that some of Bercow’s Twitter followers (over 56,000 people) would have knowledge of the extrinsic facts necessary to understand the innuendo; if they followed her they were probably interested in politics and aware of the high profile accusations broadcast on the BBC the night before. It was not necessary for them to know specifically who McAlpine was, the use of the title ‘Lord’ identified him as someone of significance, probably in politics. Therefore, there was enough evidence to show that some of her followers would have understood the innuendo.

Twitter users with less than 500 followers who had made similar statements were allowed to make a £25 donation to charity rather than be sued.

FALSE/POPULAR INNUENDO

A false or popular innuendo does not require the reader to have knowledge of any extrinsic facts to understand the meaning. Instead it will be the use of allusion, slang or the juxtaposition of image and words that reveals the meaning (Lewis v Daily Telegraph (1964) (HoL)).

An article published by the defendant stated that a company owed by Lewis was under investigation by the Fraud Office. When the company was found not to have done anything wrong Lewis sued the paper for defamation arguing that its readers would have ‘read between the lines’ of the article and understood the innuendo that the company was guilty of committing fraud. The court disagreed; the right-thinking man would not automatically assume that the company was guilty purely on the basis of reading that they were under investigation.

In Plumb v Jeyes Sanitary Compounds (1937) a photo of a policeman was used without his permission to advertise a foot bath. The photo was accompanied by the words, ‘Phew, I’m dying to get my feet into a Jeyes Fluid foot bath’. The claimant argued that the innuendo was that his feet were so smelly that they required a special foot bath. He successfully sued the company for defamation.

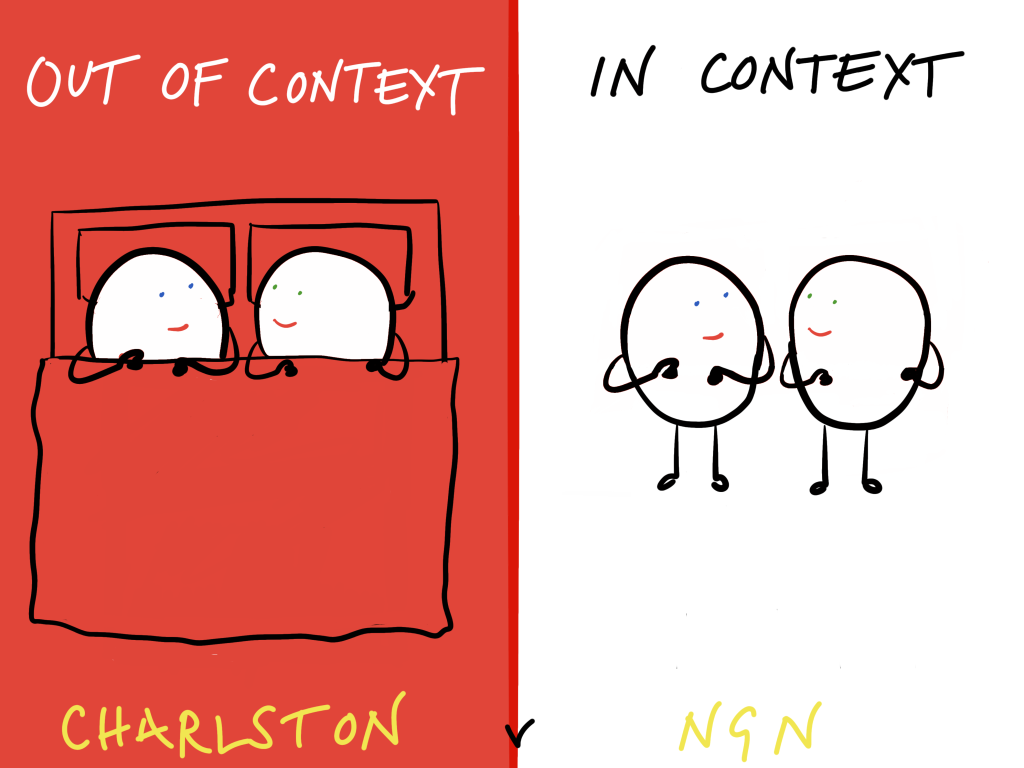

CONTEXT

The context in which the statement was made will go towards deciding whether it is capable of being defamatory. For example, shouting that someone is hideously ugly in a face-to-face spat would probably not be seen as defamatory because it was something said in the heat of the moment.

A statement cannot be made defamatory by being taken out of context (Charleston v News Group Newspapers (1995) (HoL)).

A photograph of two actors from the series Neighbours having sex was not defamatory because in the caption and story it was made clear that the photo was not real.

STATEMENT REFERS TO THE CLAIMANT

The test is, does the reasonable reader on seeing the statement believe it to refer to the claimant? If the statement uses a nickname or generic title (i.e. Headteacher), the test will then be, does the reasonable reader with the extra knowledge required believe it to refer to the client? In this scenario the claimant will have to prove that there were readers who would have been able to connect the statement with the claimant, otherwise there will have been no defamation of character.

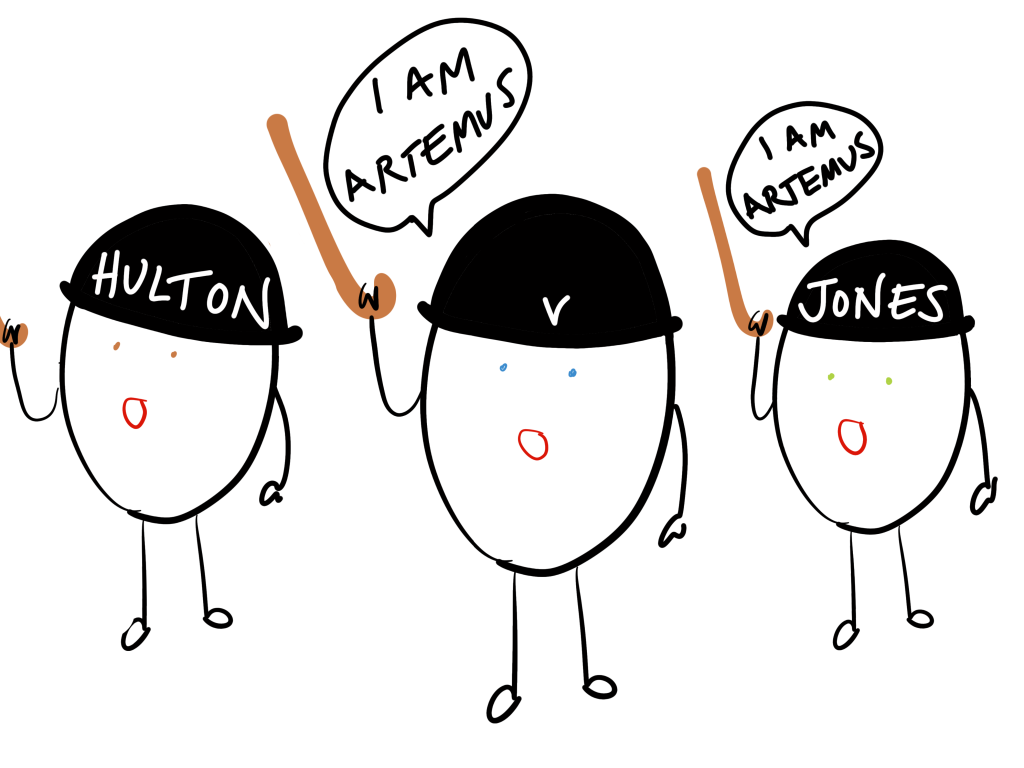

It is not necessary for the statement to have actually been about the claimant as long as they can prove that people who read the statement believed it to be about them (Hulton & Co v Jones (1910) (HoL)).

A newspaper published a story about a church warden called Artemus Jones who went to a car rally in Dieppe and cheated on his wife. Someone else called Artemus Jones, who was not a church warden but a barrister and had never been to Dieppe, was able to prove that several people had believed the article to be about him and was able to bring a case for defamation against the publisher.

In Newstead v London Express Newspapers (1940) (CoA) a newspaper report identified Harold Newstead, a 30 year old man from Camberwell, as the defendant in a trial for bigamy. Unfortunately there was another 30 year old man called Harold Newstead who lived in Camberwell who successfully sued for defamation. Although this places a burden on publishers to ensure that they provide enough details to specifically identify the correct person the potential harm done to the claimant was seen as outweighing this burden.

PICTURES

In O’Shea v Mirror Group Newspapers (2001) (HC) the defendant newspaper published an advert for a porn website.

The image of the woman used in the advert looked very similar to the claimant who sued for defamation. She was unsuccessful; although the court agreed that there was a common law case for defamation it also held that there was a difference between words and pictures and to place the burden on publishers to not publish any picture that looked similar to someone else went against Article 10 HRA (Freedom of Expression).

However, this would not be the case if the photograph was actually of the claimant. In 2014 the police paid damages to a man whose photograph had been incorrectly sent to the press as an image of a rapist that they were looking for.

REFERENCE

A statement can be defamatory by referring to the claimant without actually naming them (Cassidy v Daily Mirror Newspapers (1929) (CoA)). A photograph of Mr Cassidy, a famous racehorse owner and former General of the Mexican Army, with a woman who was not his wife was published in the newspaper with a caption stating that they were engaged. Mrs Cassidy, who did not live with her husband but still saw him sometimes at her workplace, sued for defamation; the photograph of him and his ‘fiancé’ could lead people to believe that she was not actually his wife and had been living with him immorally (i.e. without being married). She was able to produce several witnesses who said that after seeing the article they had thought she had been lying about being his wife and was in fact his mistress. This is also an example of innuendo; the hidden meaning of the photograph was that Mr Cassidy was not already married.

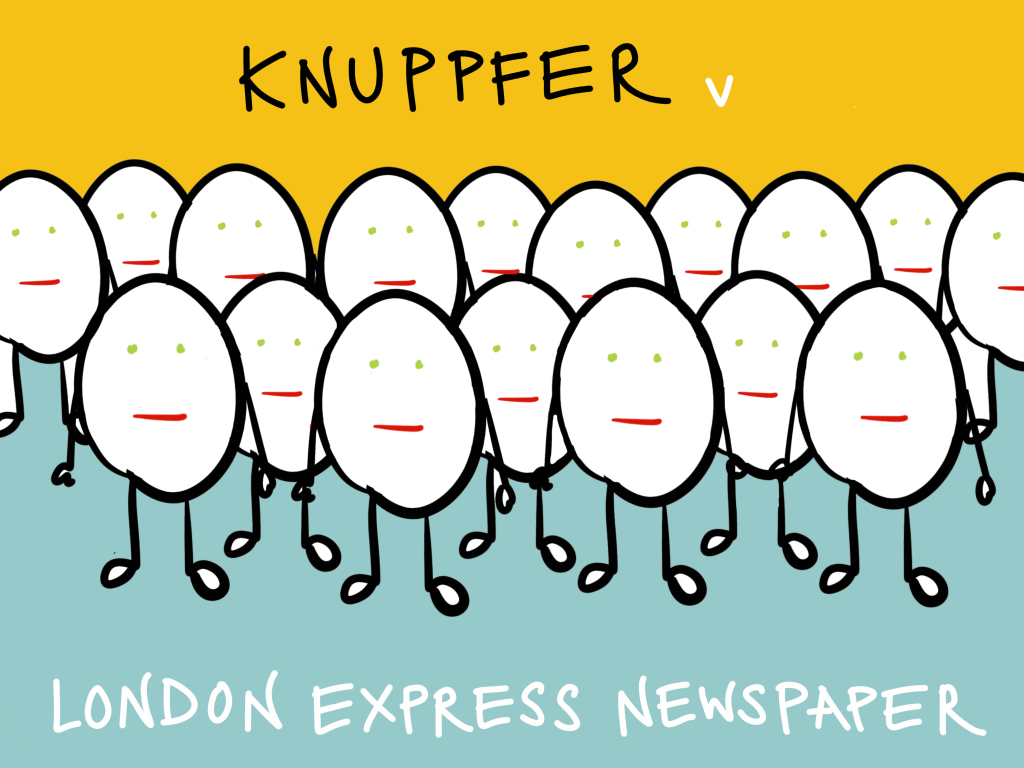

MEMBERS OF A GROUP

In general, statements made that refer to a group of people without making reference to any individual cannot be defamatory. For example, saying ‘everyone who lives in Chelmsford is a criminal’ would not be defamatory because no individual is identifiable. However, this may not be the case if a group is small enough, for example ‘my next door neighbours are criminals’, as this could be only two people.

In Knuppfer v London Express Newspaper (1944) (HoL) the defendant published an article that accused members of Mlado Russ (a Russian political party) of ‘quisling activities’, i.e. sympathising with the Nazis. The leader of the party in Britain sued for defamation arguing that the party in Britain (24 members) was sufficiently small for the statement to refer specifically to him. The court disagreed; the statement encompassed all members including those abroad, of which there were thousands, making the group much larger and the claimant less specifically identifiable.

In Farrington v Leigh (1959) an article in The Observer referring to ‘Stalker’s Men’ was precise enough to be defamatory. The term referred to the policemen who worked under Chief Constable Stalker, a small enough group to be individually identifiable.

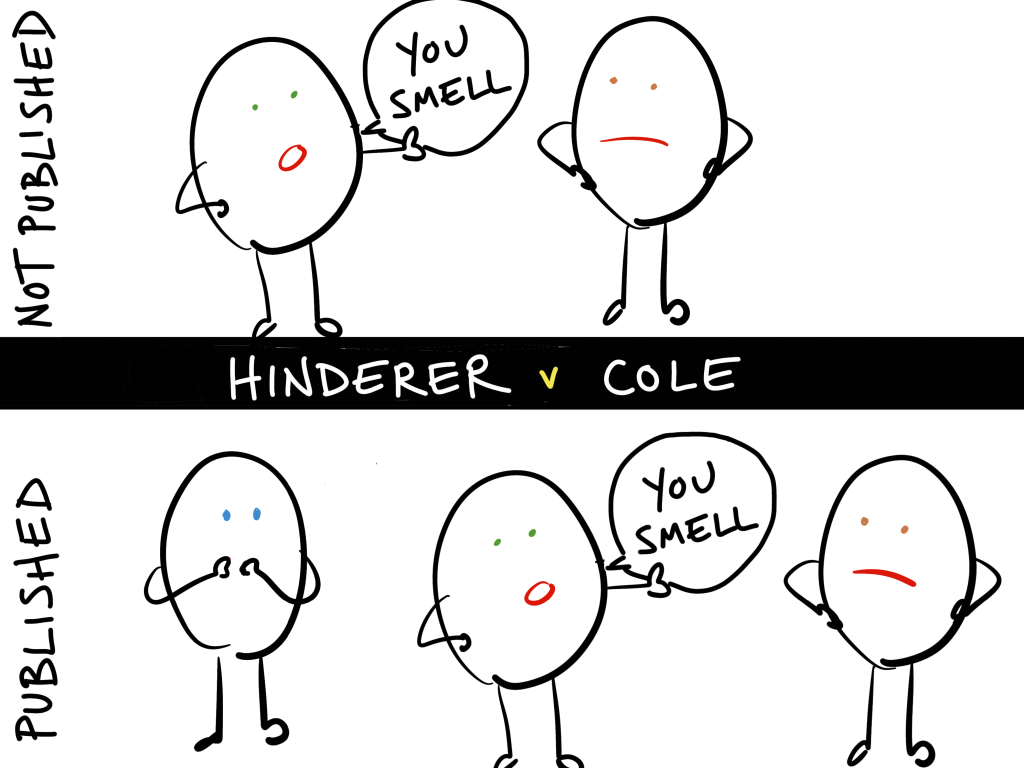

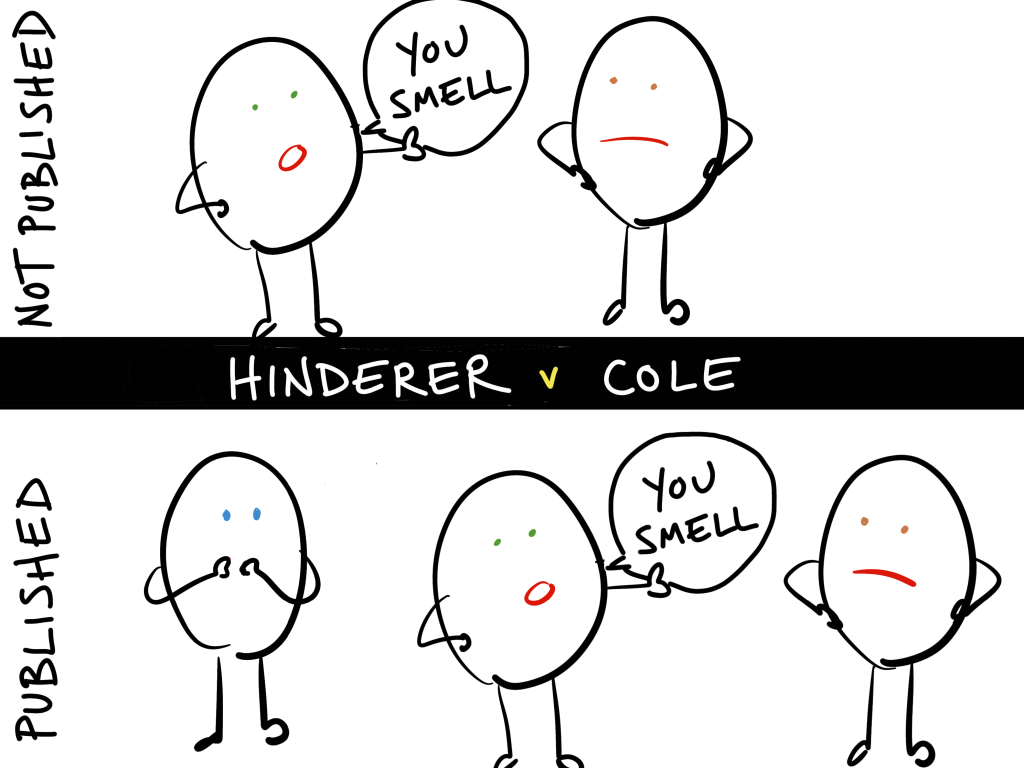

PUBLICATION OF THE STATEMENT

The statement must have been published to someone other than the claimant to be defamatory (Hinderer v Cole (1977)). In this context published means communicated, so includes all types of statement whether written, recorded or spoken.

The defendant sent a letter containing defamatory statements to the claimant. The claimant then showed this to other people. The statements could not be defamatory because the defendant had not published them to anyone other than the claimant. It was the claimant who had then shown them to others, therefore the defendant was able to use the defence of volenti non fugit injuria. The claimant was however able to recover for a defamatory statement written on the envelope as this could have been seen by others.

Traditionally it was only necessary that the statement was seen by one other person as the claimant did not have to prove actual damage. However, since the Defamation Act 2013 s.1(1) the requirement is that the statement caused ‘serious harm’. Whether the statement caused serious harm if only seen by one other person will depend on who that person was and the nature of the statement.

If it was reasonably foreseeable that a third party would see a statement, even if it was intended only for the claimant, then the statement can be classed as published to a third party (Theaker v Richardson (1962) (CoA)). The defendant, who was running in the local council elections, wrote the claimant a letter that accused her of shoplifting and stated that she was ‘a very dirty whore’. Her husband, who was also running in the elections, opened the letter thinking it was an official election pamphlet from the candidate. The court held that it was reasonably foreseeable that the claimant’s husband would have opened the letter.

In Huth v Huth (1915) (CoA) it was not reasonably foreseeable that the butler would open a letter from a husband to his wife that contained defamatory statements about her and their children. It was not an ordinary part of a butler’s duties to open the post.

A statement made by one spouse to the other, even if seen or heard by a third party, will not have been published (Wennhak v Morgan (1888) (HC)). A husband who made a statement to his wife about a servant could not be liable for defamation as a married couple were deemed to be one entity.

OTHER FORMS OF PUBLICATION

There are certain circumstances in which it is automatically assumed that the statement has been published.

- Anything written on a postcard or open letter sent through the mail.

- Any letter or document opened and then left out where it can be seen by others.

- Words spoken loudly between two people that can be overheard by others (White v JF Stone (1939)).

- Dictation of a statement to a secretary (Osbourn v Thomas, Boulter & Sons (1930)).

- Anything published on the internet.

- Statements made to the claimant’s spouse.

REPEATING/REPUBLISHING

A defendant can be liable for repeating, or republishing, a defamatory statement made by someone else. It is no defence to state that you were merely repeating what someone else said.

Previously, every instance of ‘publication’ could lead to a separate case of defamation. However, s.8 Defamation Act 2013 creates a ‘single publication rule’. The one-year limitation on bringing a case for defamation will not reset when the statement is republished unless the republication is materially different from the original, taking into consideration the prominence and extent of the manner of publication. For example, being published in the same newspaper but on a more prominent page.

A defendant will not be liable for the repetition of their own defamatory statement unless; they authorised the repetition and intended it to be repeated, the person repeating the statement only did so under a legal or moral duty, or republication was reasonably foreseeable.

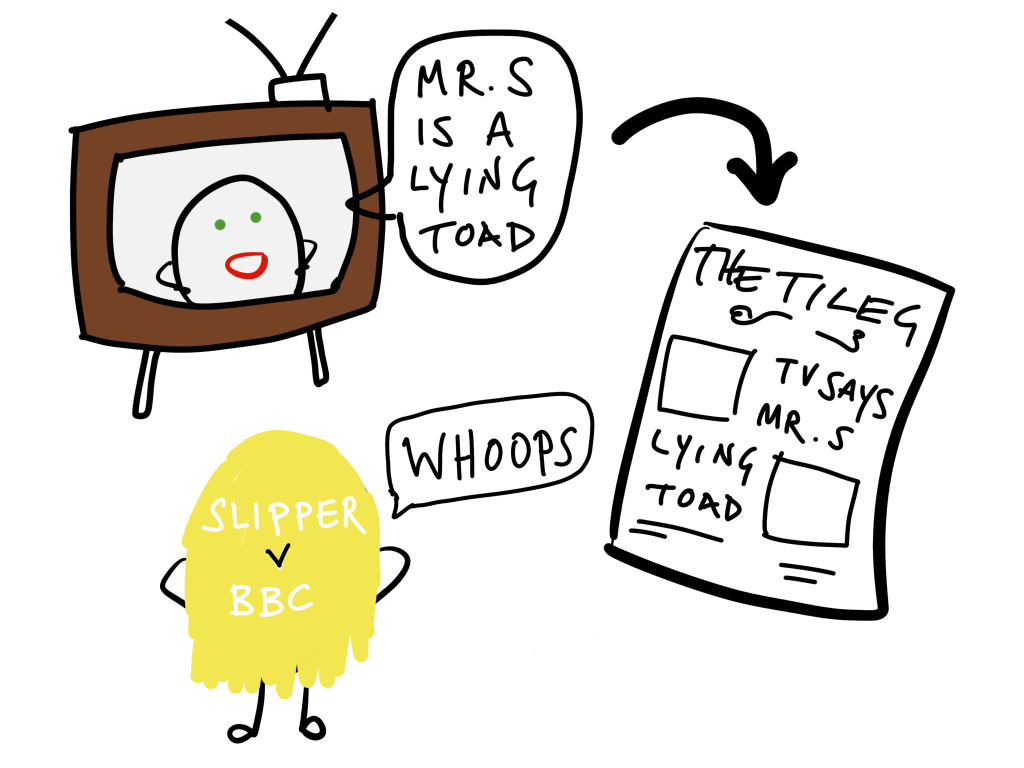

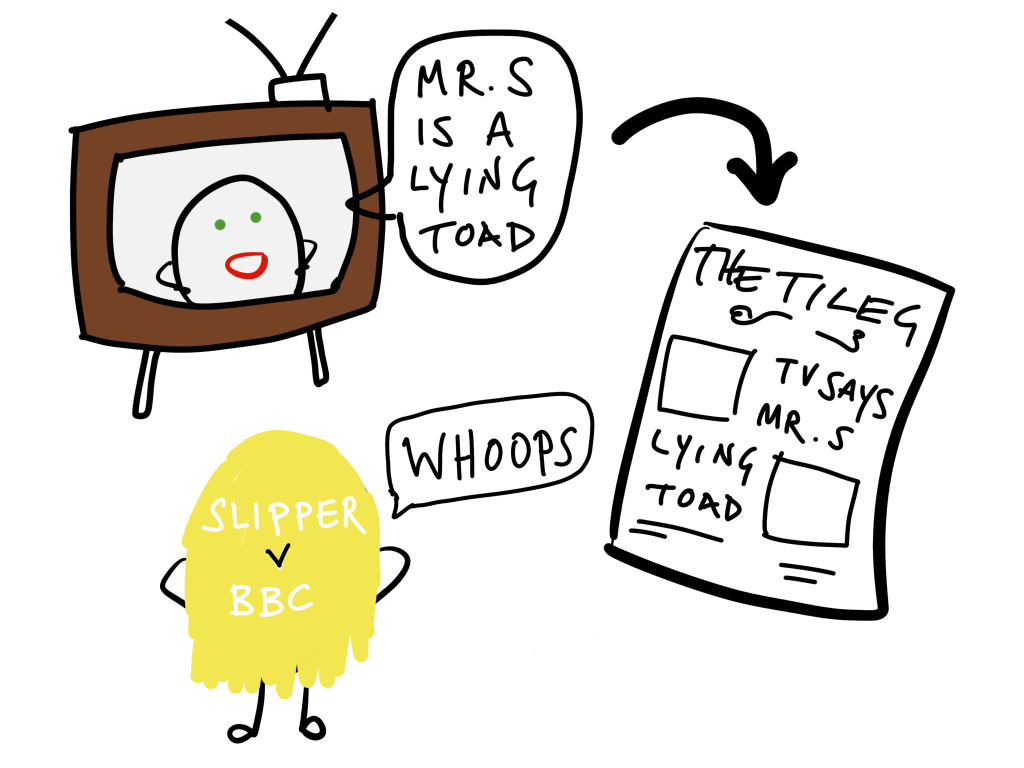

In Slipper v BBC (1991) (CoA) a TV programme made defamatory statements about the claimant. The statements were repeated by papers reviewing the programme. The BBC tried to argue that they were only liable for the original TV publication. The court held that as a matter of remoteness, republications in reviews were reasonably foreseeable and therefore the claimant could recover for damages from the defendant for the republications as well.

DEFENCES

Defamation has its own defences, very different from other torts. They are; truth, privilege, honest opinion and publication on a matter of national interest. The burden of proof lies with the defendant.

TRUTH

A statement will not be defamatory if the imputation of the statement was substantially true. This is stated in s.2(1) Defamation Act 2013. This is a complete defence. The claimant does not have to prove that the statement was untrue, it is up to the defendant to prove that it was substantially true. A good example of this is Grobbelaar v News Group Newspapers (2002) (HoL).

Bruce Grobbelaar (a professional goalkeeper) was involved in a sting by the Sun Newspaper. He was filmed accepting a bribe to throw a match and admitting to having thrown previous matches. When the Sun published the headline ‘Grobbelaar took bribes to fix games’ he sued for libel. The Sun argued that the imputation of the statement was that he had conspired to throw matches which they could prove from his taped admission. Grobbelaar argued its imputation was that he had actually thrown matches which he claimed he could disprove from evidence of how well he had played in those matches. The jury agreed with Grobbelaar; the imputation of the statement was that he had actually fixed matches, rather than simply conspiring to, and this was not substantially true. The court, however, reduced his damages to £1 to reflect the fact that he had been shown to be corrupt.

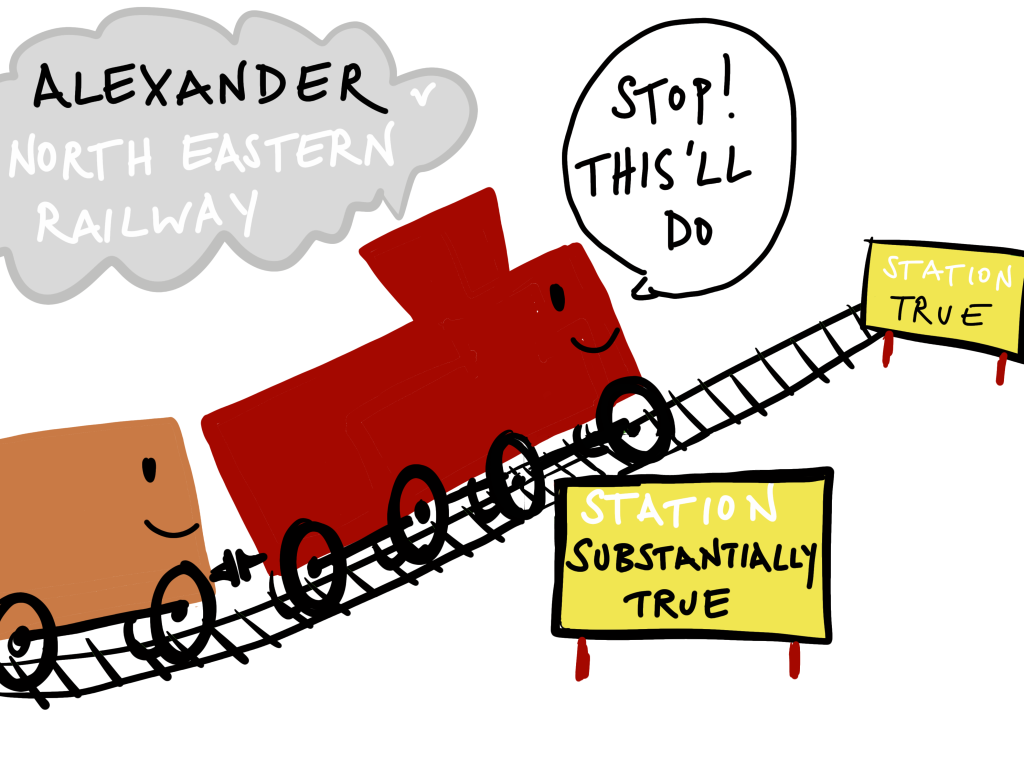

SUBSTANTIALLY TRUE

The defendant does not need to prove that everything they published was true, just that it was substantially true (Alexander v North Eastern Railway (1865)).

The railway published a poster stating that the claimant had been charged with travelling without a ticket and imprisoned for three weeks. Alexander sued because he had in fact only been imprisoned for two weeks. There was no defamation because the railway’s statement was substantially true.

In Depp v News Group Newspapers (2020) (HC) the defence of truth was successfully used by the defendants. The defendant had claimed that Depp had acted violently towards his wife and was a wife beater. There were fifteen specific incidences of violence that were put forward as evidence by the defendant. The judge found that eleven of these could be proved on the common law standard of the balance of probabilities. They did not have to prove that every single incident was true.

A criminal conviction is sufficient evidence of the truthfulness of a statement that refers to the crime (s.13 Civil Evidence Act 1968).

ABSOLUTE PRIVILEGE

Absolute privilege is available in the following circumstances;

- statements made in Parliament,

- statements made in official Parliamentary papers,

- statements made during judicial proceedings,

- statements made between officers of state in the course of official dealings,

- statements made between lawyers and their clients.

Even if these statements are completely untrue and made with malice they are safe from action for defamation. The rationale for this is that in these situations the participants should have complete freedom of expression.

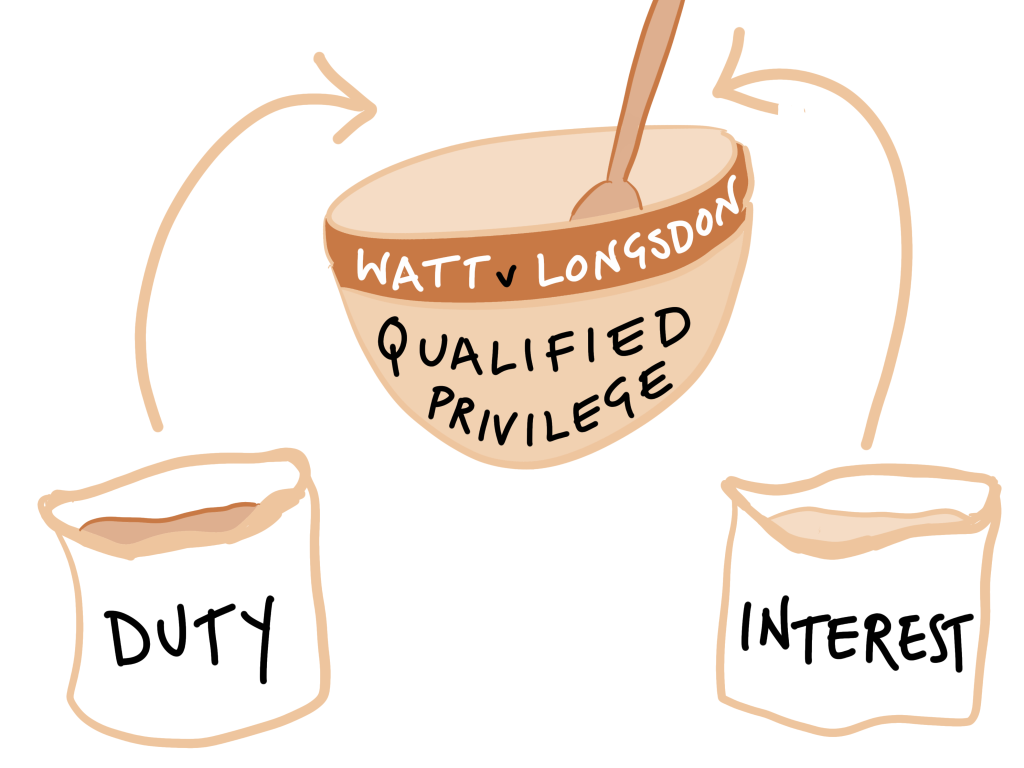

QUALIFIED PRIVILEGE

Qualified privilege applies if it can be shown that the maker of the statement had a duty to make it and the recipient had an interest in receiving it. This reciprocity between the two parties is essential.

DUTY & INTEREST

The maker of the statement must be able to show that they had a duty to make the statement and that the recipient had an interest in receiving it. This is more than merely finding the information interesting, there must be a reason why it is important that they receive the information (Watt v Longsdon (1930) (HC)).

The claimant was working overseas for a company when the defendant, one of the Company Directors, received notice that he was behaving in a way that reflected badly on the company including cheating on his wife. The defendant passed on this information to the Chairman of the company and the claimant’s wife. The information was untrue and the claimant sued. The court held that the passing of defamatory information to the Chairman was covered by qualified privilege because the defendant had believed it to be true and therefore had a duty to pass the information on and the Chairman had a genuine interest in receiving the information. However, passing the information onto the wife was not covered by privilege. Although she may have been interested she had no valid interest in receiving the information that could be defended by privilege.

Section 6 Defamation Act 2013 gives rise to another category of qualified privilege. The publication of a statement in a scientific or academic journal is privileged if the following conditions are met; the statement relates to a scientific or academic matter and that before the statement was published in the journal an independent review of the statement’s scientific or academic merit was carried out by the editor of the journal, and one or more persons with expertise in the scientific or academic matter concerned.

MALICE

Qualified privilege will not apply if the statement was made with malice. A statement will have been made with malice if it was made with the intention of defaming the claimant, or the defendant knew it to be untrue or was careless as to whether it was true or not. If the defendant made the statement with an honest belief in the truth of the statement then it will not have been made with malice. The burden of proof is on the claimant to prove malice.

In Angel v HH Bushell (1968) the defendant wrote to a fellow businessman stating that the claimant was ‘not conversant with normal business ethics’. When the claimant sued the defendant claimed that qualified privilege applied because he had a duty to inform and the recipient an interest in receiving this information. However, the court found that the statement had been made in anger and therefore with malice so he was unable to use the defence of qualified privilege.

In Lillie v Newcastle City Council (2002) (HC) a report issued by the council claimed that several people working at a nursery had abused children even though there was no evidence for this. Although the report was covered by privilege the court held that the statement was made with malice and therefore qualified privilege did not apply.

PUBLIC INTEREST

A statement will also be privileged if it was published in the public interest. This is now enshrined in s.4 Defamation Act 2013;

(1)It is a defence to an action for defamation for the defendant to show that—

(a)the statement complained of was, or formed part of, a statement on a matter of public interest; and

(b)the defendant reasonably believed that publishing the statement complained of was in the public interest.

This was based on the previous common law defence from Reynolds v Times Newspapers (2001) (HoL) although the Defamation Act 2013 technically abolishes the Reynolds defence (s.4(6)).

The Sunday Times had published an article stating that Albert Reynolds, the former PM of the Republic of Ireland, had misled Parliament. He sued and won. The court held that although the article was of public interest it was not sufficiently important to be in the public interest and therefore was not covered by privilege. The case was nonetheless important because Lord Nicholl’s set out a framework for assessing when news stories would be privileged. He listed ten factors of responsible journalism that should be taken into account when assessing whether a statement was in the public interest. This is not an exhaustive list but rather a framework.

They were; the seriousness of the information, the nature of the information, the source of the information, the status of the information, the urgency of the matter, whether the claimant was asked to comment, whether the claimant’s side of the story was included, the tone of the article and the circumstances of the publication. The aim was to find a balance between freedom of expression on matters of public concern and the reputation and right to privacy of the person concerned.

This was seen as the creation of a new defence, rather than extending qualified privilege, and aimed at defending the freedom of the press to inform the public on important matters, especially within the political arena. Lord Nicholls stated that any ambivalence as to whether something was published in the public interest should be decided in favour of the defendant.

EXAMPLES OF PUBLIC INTEREST CASES

The Act contains no definition of public interest as it was deemed sufficiently defined by existing case law. The following cases are good examples.

In Grobbelaar v News Group Newspaper (2001) (HoL) the tone of the article, described as a ‘sustained and mocking campaign of vilification’ against the footballer, was one reason why the article was not protected by privilege. This was not seen as responsible journalism that merited protection by the law.

In Jameel v Wall Street Journal (2003) (HoL) the defendant had published an article claiming that the Saudi Arabian authorities were monitoring certain banks at the request of the US government for transactions to terrorist organisations. Jameel was the owner of one of the banks named. The court held that the matter was of public interest and covered by privilege. They also stated that when considering whether an article is of public interest the whole article must be considered as one, it is not possible to extract specific phrases, it is the “thrust” of the article that should be considered.

In Flood v Times Newspapers (2013) (HoL) the paper had published a story about an allegation of bribery and corruption in the police force, naming the claimant as the recipient of bribes from a Russian oligarch. The court ruled that the story was published in the public interest and fulfilled the requirement of ‘responsible journalism’; it had not stated that the allegations were true but only the basis for an investigation, the claimant was given the opportunity to comment and his denial was included, and it was published with the legitimate aim of ensuring the allegations were properly investigated by the police in circumstances where the journalist had good reason to doubt that they would be.

The court also emphasised that any court should be slow to interfere with the discretion of the editor in deciding to publish, this is now included in s.4(4) Defamation Act 2013.

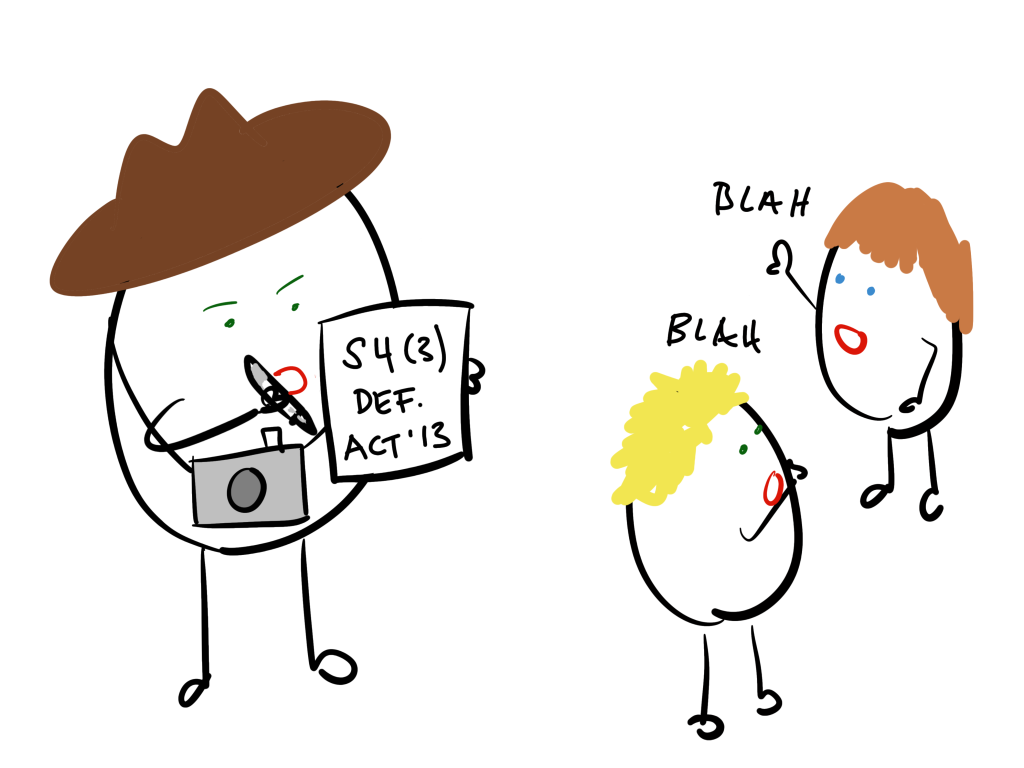

REPORTAGE

The common law doctrine of reportage, which was first suggested in the case of Al-Fagih v HH Saudi Research and Marketing (UK) Ltd (2001) (CoA) and further set out in Roberts v Gable (2007) (CoA), was incorporated into s.4(3) Defamation Act 2013 as part of the Public Interest defence. If the defendant can show that the statement ‘was, or formed part of, an accurate and impartial account of a dispute’ (s4(3)) and the publisher of the statement merely reported the dispute in a neutral way, ‘without adoption or embellishment or subscribing to any belief in its truth of attributed allegations’ (Robert v Gable (2007) (CoA)) then the publisher need not have taken the time to verify the truth of the imputation of the statement.

This defence lies within the defence of public interest so the other factors as set out in Reynolds still apply. Arguing that a statement was reportage gives the publisher more leeway in whether or not they took the time to absolutely verify the details of the statement before publication. For example, in some cases this takes time and the story loses its interest if not reported straight away.

HONEST OPINION

Originally a common law defence known as honest or fair comment, the defence of honest opinion has now been legislated for in s.3 Defamation Act 2013.

In order for honest opinion to be successful;

- the defamatory statement must be an opinion,

- the statement indicated, whether generally or specifically, the factual basis for the opinion, and

- an honest person could have held the opinion based on fact.

OPINION

The statement must be one of opinion and not fact. In theory it should be easy to distinguish between fact and opinion but in some cases it has proved difficult. In British Chiropractic Association v Singh (2010) (CoA) the defendant had published an article stating that there ‘was not a jot of evidence’ that chiropractic treatment worked for several specified conditions. When the claimant sued Singh relied upon the defence of fair comment (pre Defamation Act 2013) arguing that his comment was an opinion not a fact. However, the Court of Appeal disagreed. The phrase meant that there was ‘no worthwhile or reliable evidence’ and this was a value judgement and therefore an opinion not a fact.

FACTUAL BASIS

The statement must also set out what facts the opinion is based on, whether in general or specifically. It need not be so specific that the reader would be able to form their own opinion just from reading the statement but it must give the reader at least a general impression of what led to that opinion (Joseph v Spiller (2010) (SC)).

HONESTLY HELD

The defendant must show that their opinion, based on the stated facts, would also have been held by an honest person who knew the same facts. It does not have to be reasonable for them to have held that view and it does not matter if the opinion is prejudiced or exaggerated.

Honest opinion is not available as a defence if it can be shown that in fact the defendant did not hold that opinion.

INNOCENT DEFAMATION

A defendant can use the defence of innocent defamation as set out in Section 1 Defamation Act 1996. This is a defence for parties that are ‘mechanical distributors’, i.e. they automatically publish material rather than have control over the content. The defence covers such parties as libraries, newsagents, booksellers, any sellers of materials, broadcasters of live programmes and providers of communication services such as social media and website hosts. It cannot be used by editors, authors or publishers.

In order for the defence to work the defendant must show that;

- they were not the author, editor or publisher of the statement

- they took reasonable care over its publication, and

- did not know or had no reason to believe that their action caused or contributed to the publication of a defamatory statement.

In Godfrey v Demon Internet (2001) (HC) although the defendant was merely the host of a site containing a defamatory statement they failed to delete it once notified of its existence by Godfrey. Therefore they had known that their actions (or lack of action) had contributed to the publication of a defamatory statement and they could not use the defence.

WEBSITE OPERATORS

Section 5 Defamation Act 2013 set out a specific defence for website operators. If the operator can show that they did not post the statement on the site then they will not be liable for defamation (similar to innocent defamation above). However, the defence will not be available if;

- it is not possible for the operator to identify who posted the statement,

- the claimant gave the operator a notice of complaint in relation to the statement, and

- the operator failed to respond to the notice of complaint in accordance with any provision contained in regulations.

In Tamiz v Google Inc (2013) (CoA) Google were deemed to be the publishers of statements made on a blog hosted on blogger.com. Google failed to take down the defamatory statement after notification by Tamiz. At this point they knew, or should have known, that their failure to take down the statement was contributing to its continued publication.

The defence will also be defeated if it can be shown that the operator acted with malice.

OFFER OF AMENDS

In some cases the defendant can offer to make amends to the claimant. This is not strictly a defence but a way of avoiding a full trial. An offer must be made by the defendant before they have served their defence. In order to make amends the defendant must offer to publish an apology and correction, and pay the claimant’s legal fees and agreed compensation.

In Cleese v Clark (2004) (HC) the Evening Standard had published an article about John Cleese’s involvement in a failed US TV show, suggesting that he had been responsible for the programme and now faced humiliation and public vitriol in America all deserved because of his own hubris. Cleese argued that all of this was untrue, although the show was unpopular he had been praised for his role and he had not been involved in its creation. The paper admitted that the article was unfair and offered amends. As the two parties could not agree on the level of compensation this was decided by the court.

The claimant can chose whether to accept the offer of amends or not. If they refuse then their rejection can be used as a defence by the defendant (as stated in s 4 of the Defamation Act 1996).

However, this defence can be defeated by the claimant if they can show that the defendant had not acted innocently. To do this they must show that the statement referred to them and it was likely to be understood as referring to them, and was false and defamatory of them. Whether the defendant acted innocently in this context is a subjective test, based on what the defendant is shown to have known at the time. However, the defendant will not have been innocent if it can be shown that they were recklessly indifferent to the truth (Milne v Express Newspapers (2005) (CoA)). Proving this innocence falls to the claimant.

REMEDIES

Damages and injunctions are available as remedies. Injunctions are usually used to stop any further publication of the statement once the court has held that the statement was defamatory but can in some circumstances be used to prevent publication until the trial. These are called super-injunctions.

Unlike in other torts compensatory damages (to compensate for loss and any distress caused) can be supplemented by exemplary damages which are designed to vindicate the claimant and repair their reputation as well as punish the defendant.

Before John v MGN (1997) (CoA) juries were able to set the level of damages. This led to very varied levels of damages, out of proportion to anything awarded in a personal injury case. Since that case judges are able to direct the jury and guide them towards a reasonable settlement.