JUMP TO: DAMAGE | INTERFERENCE | DEFENCES | REVISE | TEST

PRIVATE NUISANCE

Private nuisance is defined as ‘…any continuous activity or state of affairs causing a substantial and unreasonable interference with a plaintiff’s land or his use or enjoyment of that land’, Bamford v Turnley (1862) (Court of Exchequer). It is not actionable per se so the claimant must show that the nuisance caused damage.

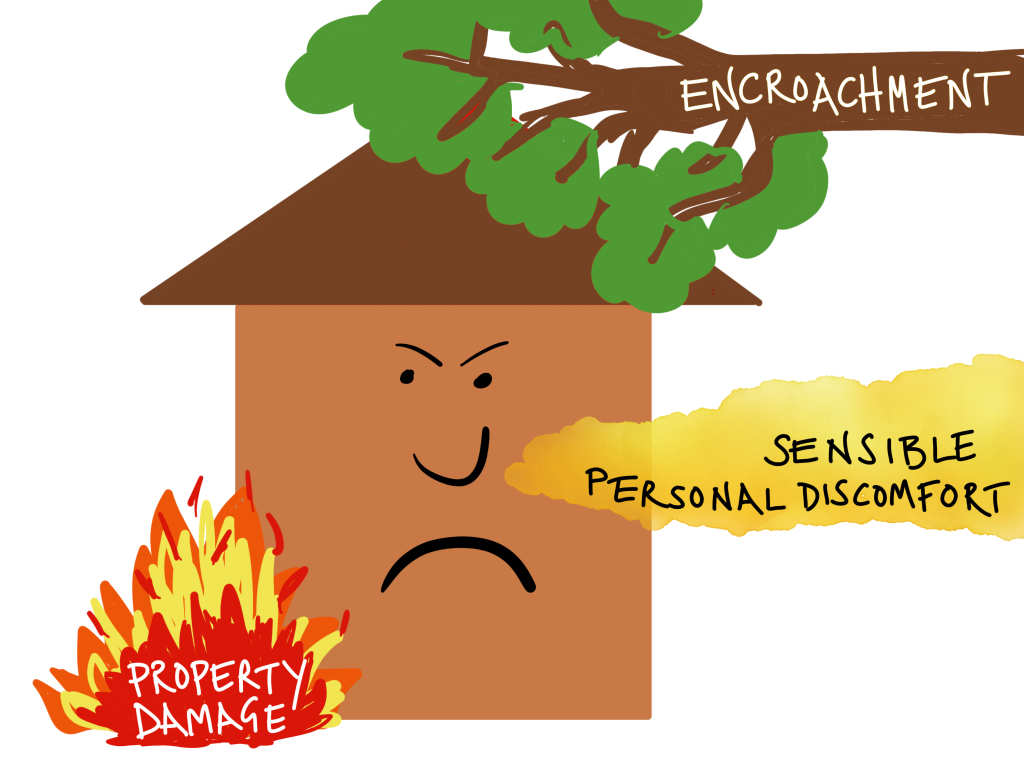

DAMAGE

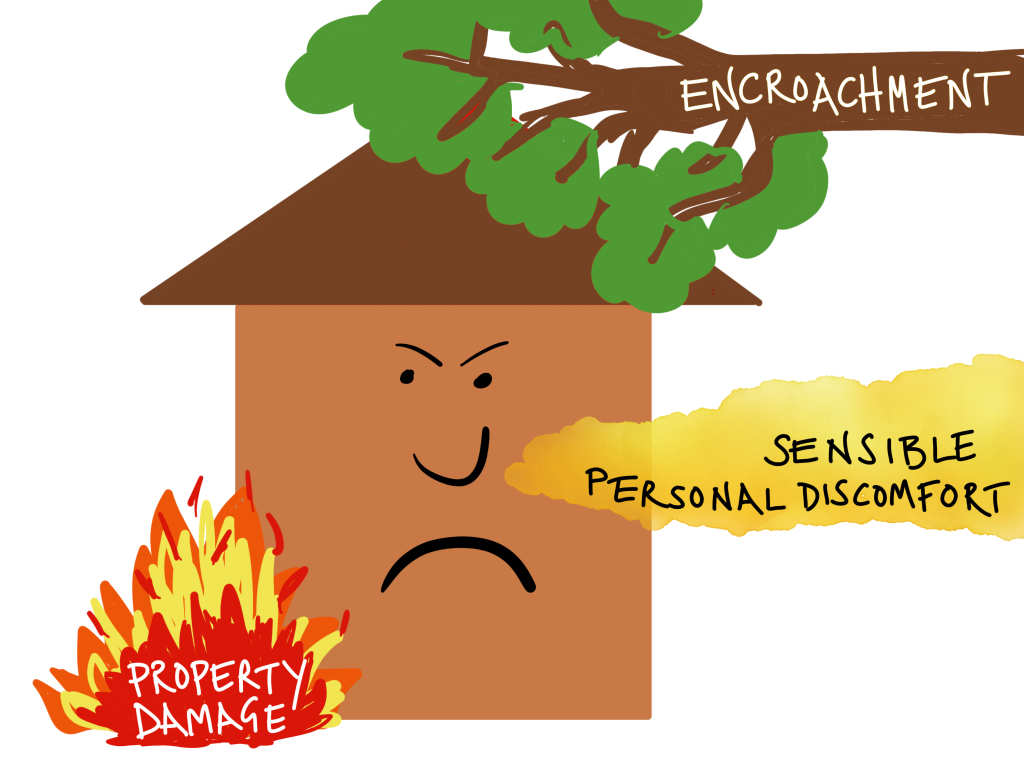

There are three types of damage that can be claimed for under private nuisance; actual physical damage, sensible personal discomfort or encroachment. The damage must be related to the claimant’s land or their use of their land. For this reason it is not possible to claim for personal injury under private nuisance.

PHYSICAL DAMAGE

An example of physical damage caused by private nuisance is St Helens Smelting Co v Tipping (1865) (HoL) in which the polluting vapours from copper smelting works caused physical damage to trees and shrubs on Tipping’s land.

ENCROACHMENT

Encroachment happens when something encroaches from the defendant’s land onto the clamant’s land. A good example is Lemmon v Webb (1895) (HoL) in which overhanging branches from a tree growing on the defendant’s land were an encroachment onto the claimant’s property.

|

SENSIBLE PERSONAL DISCOMFORT

Sensible personal discomfort refers to discomfort of the senses. Noises, smells, vibrations, etc which are caused by a nuisance and affect the claimant’s enjoyment of their property and lead to their personal discomfort.

It has been described as, ‘…the personal inconvenience and interference with one’s enjoyment, one’s quiet, one’s personal freedom, anything that discomposes or injuriously affects the senses or the nerves’, St Helens Smelting Co v Tipping (1865).

|

INTERFERENCE

The damage must have been caused by an interference with the use or enjoyment of the claimant’s land. This interference must be indirect and unlawful.

INDIRECT

An indirect interference is one that is caused by something being emitted from the defendant’s land onto the claimant’s land. For example, noises or smells travelling through the air or something falling indirectly onto the claimant’s land. A tree house falling out of a tree onto the neighbour’s land would be indirect. A child throwing something from the tree house into the neighbour’s garden would be direct.

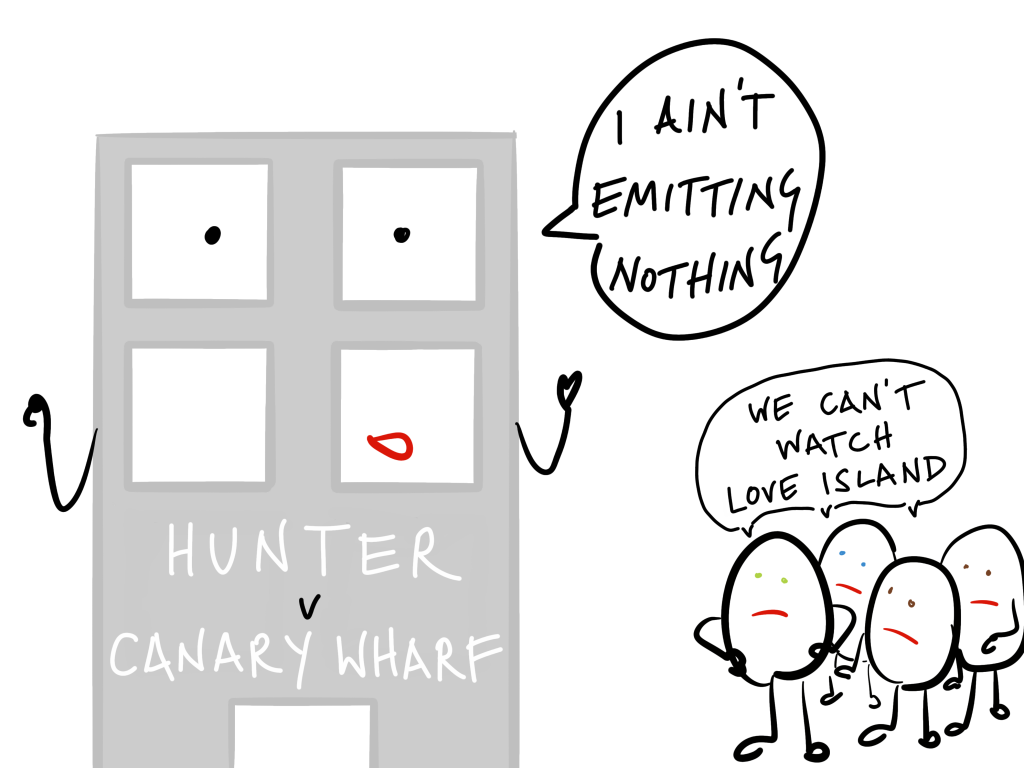

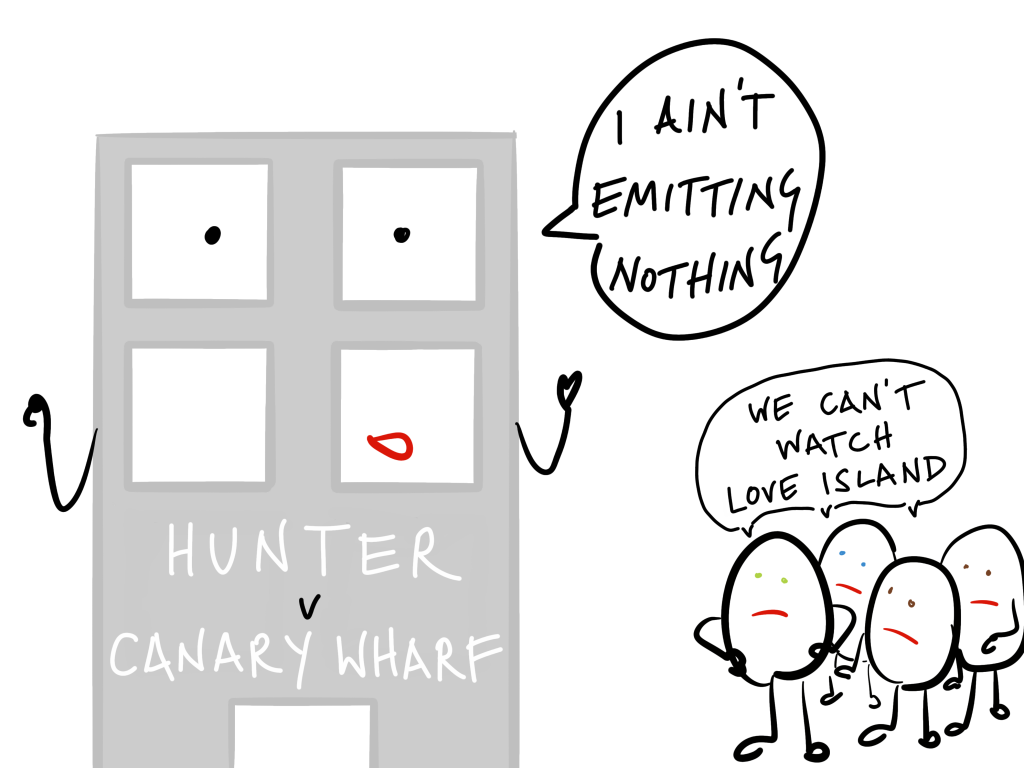

In Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997) (HoL) the claimants TV signal had been disrupted by the building of Canary Wharf tower. Their claim failed in private nuisance because although the tower was responsible for interrupting the signal it was not caused by anything being emitted from the tower, it was just the existence of the tower itself.

UNLAWFUL

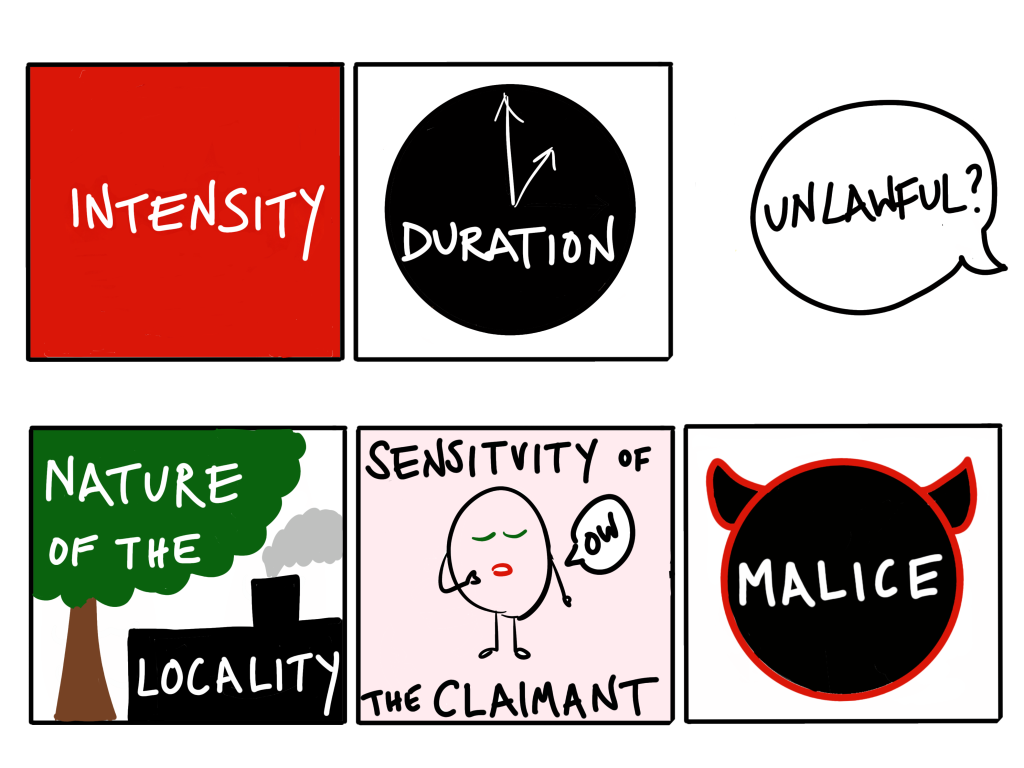

An unlawful interference in this context means that the defendant’s use of their land created a substantial and unreasonable interference with the claimant’s land, rather than necessarily being something illegal. The courts must strike a balance between allowing the defendant to use their land as they wish and protecting the claimant from interference with the use of their land. There must be a certain amount of the ‘rule of give and take, live and let live’, Bramwell J, Bamford v Turnley (1862) (Court of Exchequer).

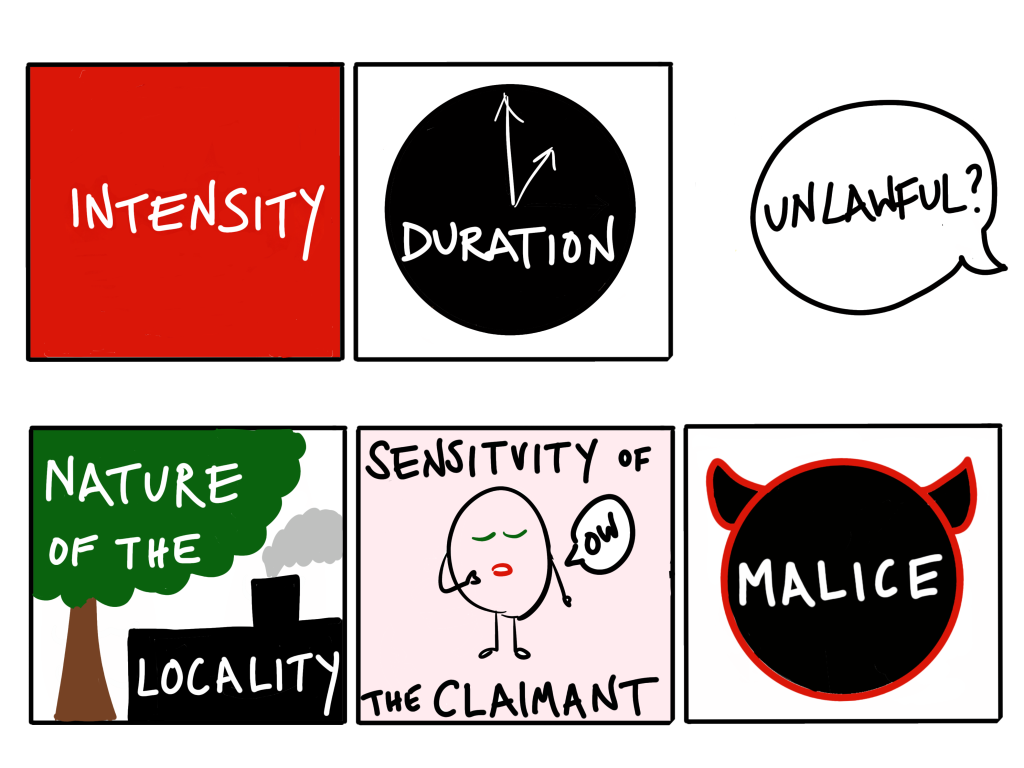

Whether the behaviour of the defendant was ‘unlawful’ will rest on the facts of the case. Over the years case law has thrown up a number of factors that the courts may, or may not, be take into consideration.

INTENSITY

If an activity is excessive then this will go towards it being a nuisance.

In Farrer v Nelson (1855) (HC) the defendant had the right to raise pheasants on his land. The birds went onto the claimant’s property and ate his crops. However, this only constituted a nuisance when the number of birds reached the hundreds and had become excessive.

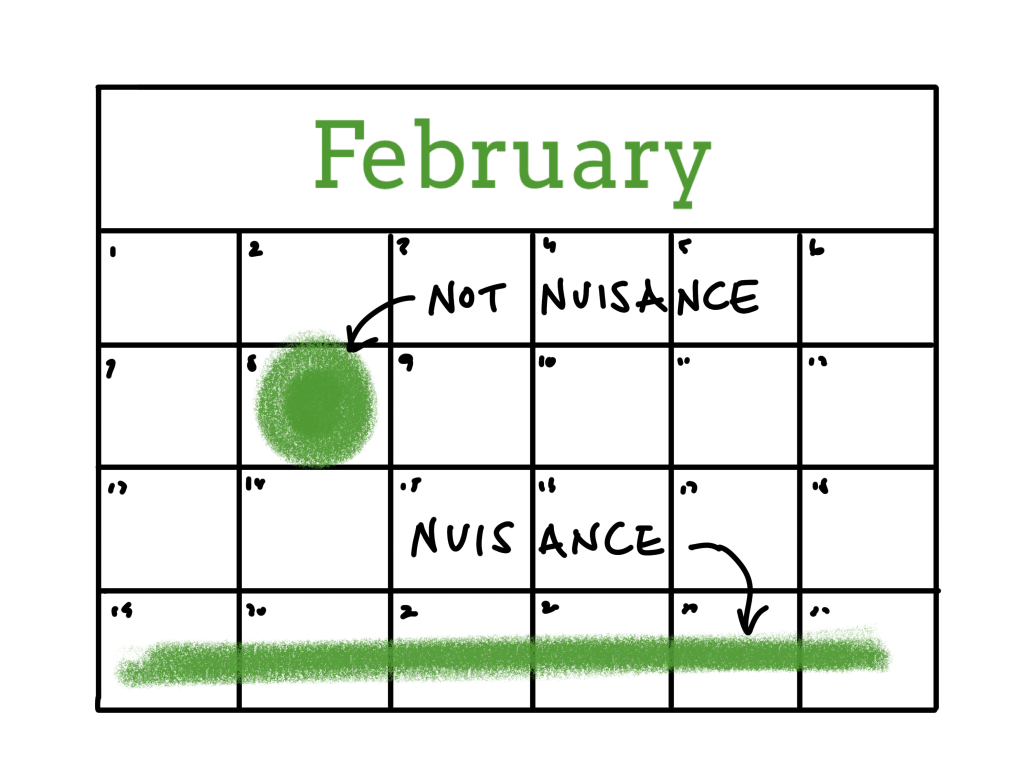

DURATION

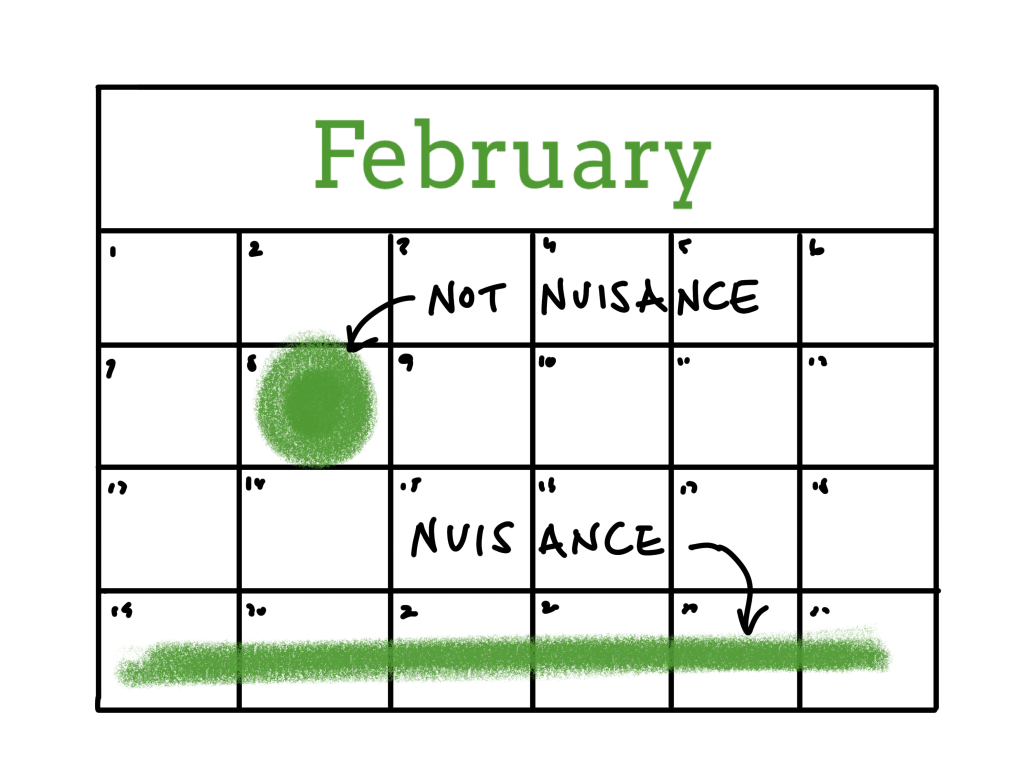

An activity that qualifies as a nuisance will usually have been continuous rather than a one-off event.

EXCEPTIONS

However, one-off events that may qualify as a nuisance are; caused by an underlying state of affairs, the ‘isolated’ event had happened before, or the damage caused was property damage.

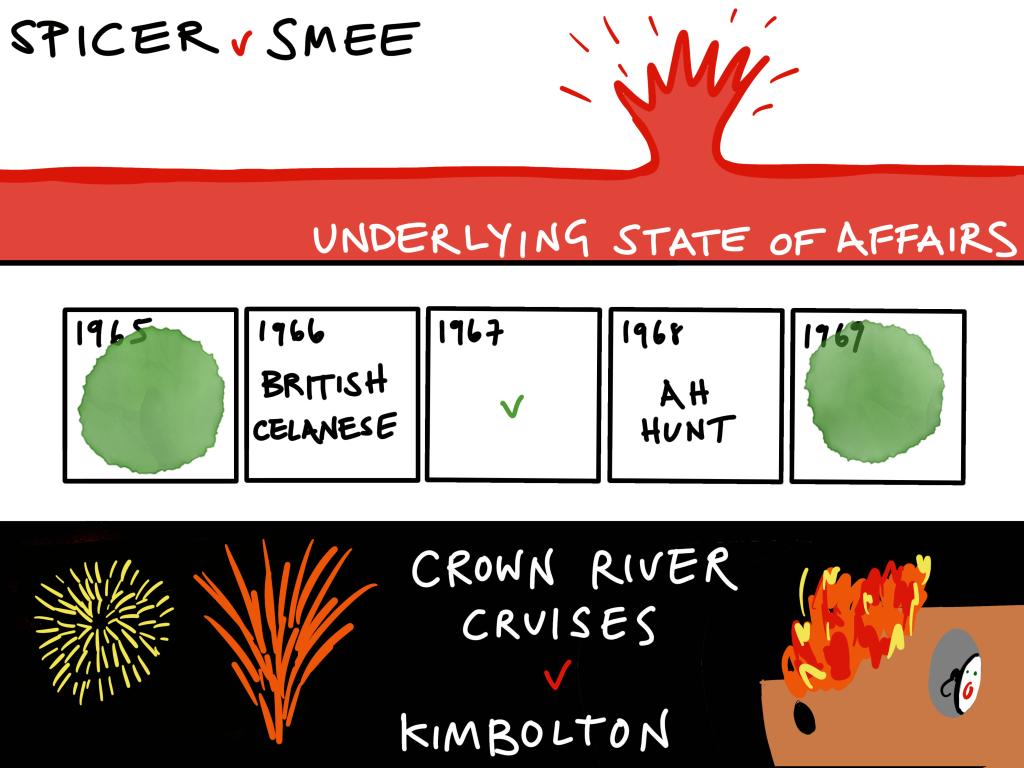

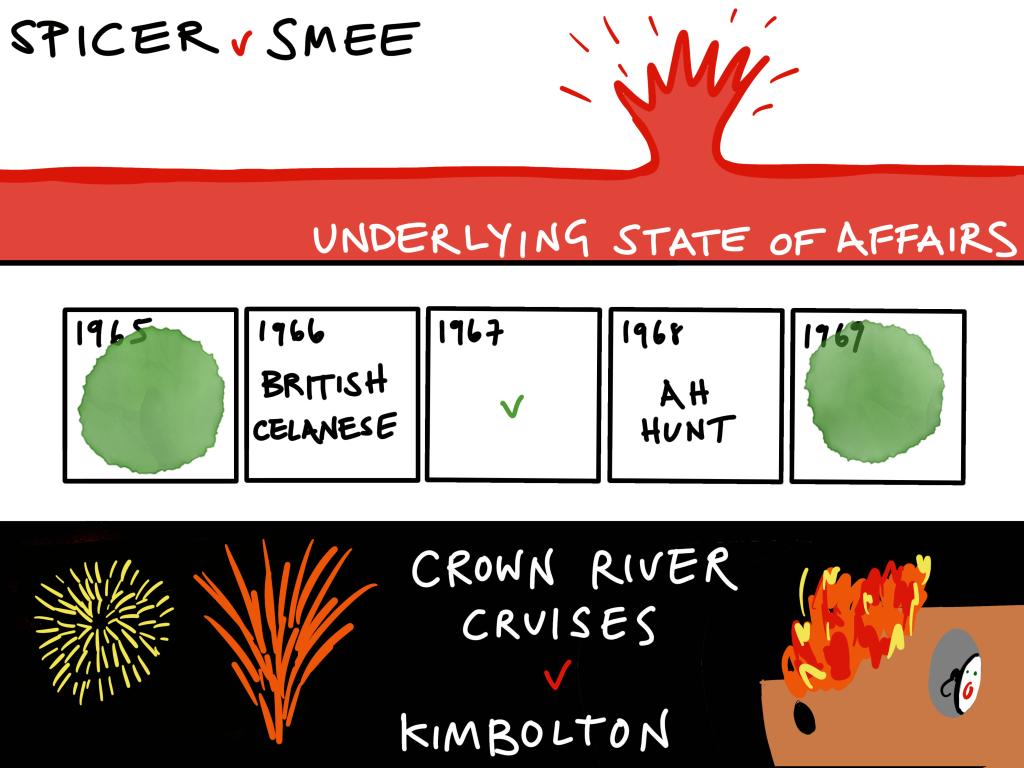

A one-off event can qualify as a nuisance if the claimant can show that it was caused by an underlying (in other words an on-going) state of affairs that was ignored by the defendant. In Spicer v Smee (1946) (HC) a fire caused by the dodgy wiring in the defendant’s property which damaged the claimant’s property was considered a nuisance because the underlying factor, the poor wiring, had been an on-going issue rather than a one-off event.

A seemingly isolated event can be a nuisance if the claimant can show that the same isolated event had happened before and, therefore, the defendant was aware of the risk of damage. In British Celanese v AH Hunt (1969) (HC) the defendant had been warned to stop foil strips emanating from its factory blowing onto the electricity substation. When the same incident occurred three years later it was not therefore considered a one-off event.

It is much more likely that a one-off event that caused physical damage will be classified as a nuisance than one that caused sensible personal discomfort. In Crown River Cruises v Kimbolton (1996) (HC) a 15 minute firework display put on as a one-off event to celebrate the anniversary of the Battle of Britain was a nuisance because it caused significant damage to the claimant’s house boat.

NATURE OF THE LOCALITY

The location of the nuisance can be taken into account by the courts in cases that involve sensible personal discomfort. If physical damage has occurred then the nature of the locality is irrelevant because physical damage should never be acceptable in any locality (St Helens Smelting Co v Tipping (1865) (HoL)).

In Sturges v Bridgman (1879) (CoA) a doctor who built his surgery in his back garden complained about the noise and vibrations emanating from a neighbouring sweet factory. This constituted a nuisance even though the claimant had built his surgery knowing about the noise. The nature of the locality was residential, therefore the factory was out of place. Thesiger J summed up the principle as, ‘what would be a nuisance in Belgrave Square would not necessarily be so in Bermondsey’. Bermondsey at that time was an area dominated by tanneries. If the doctor had built his surgery in Bermondsey then the noise may not have been a nuisance because the nature of the locality was different.

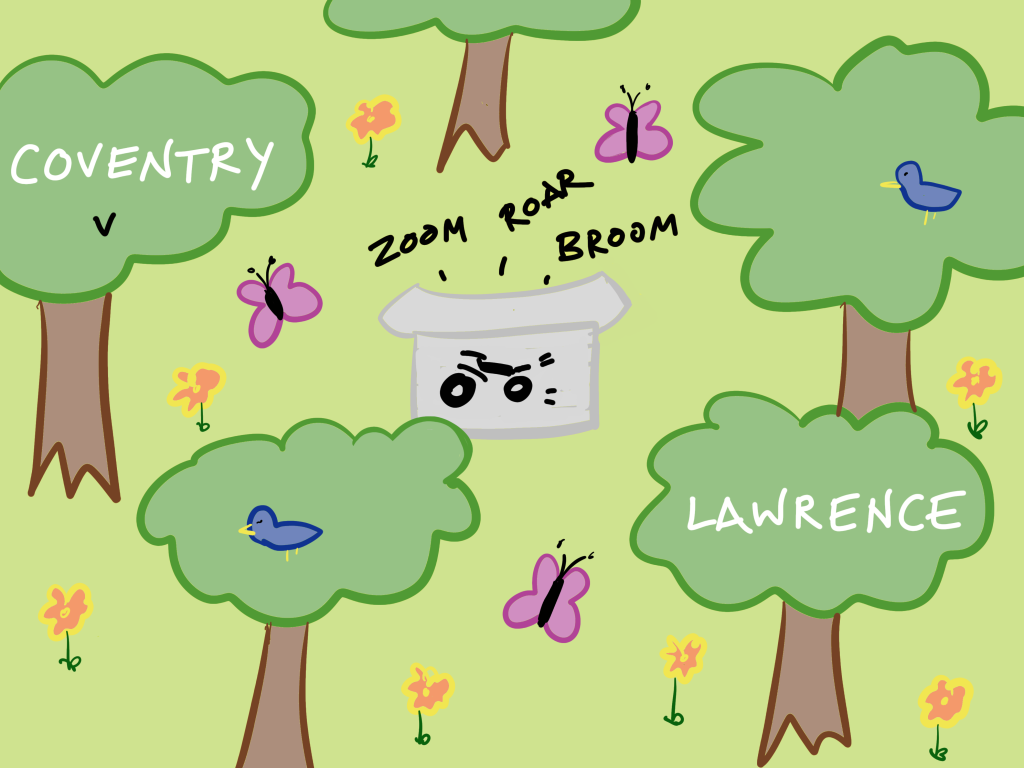

In Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC) the Supreme Court discussed how the existing activities of the defendant should be taken into consideration when deciding the nature of the locality, i.e. would the presence of a factory in a residential area mean that in fact the nature of the locality was not residential. The position held by the court was that if the activity was a nuisance, and therefore illegal, then it should not be taken into consideration. Their argument being that in most cases the nature of the locality is obvious and whether the activity is a nuisance in that locality is obvious. A couple had bought a house, in 2006, in a very rural area (the nearest dwelling was half a mile away and the nearest village 15 miles away) but only 850 yards from a noisy motor sports stadium. Despite the fact that the stadium had been there since 1975 the nature of the locality was still rural and their claim in nuisance was upheld. An injunction was placed on the activities permitted at the track but a distinction was made between the activities that were a nuisance (because of e.g. the time of day or level of noise) which were stopped and those that were not and were allowed to continue.

PLANNING PERMISSION

In Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC) the court stated that whether an activity has been given planning permission will go towards the court’s decision regarding the nature of the locality but it should never preclude claimants from bringing a claim in nuisance. In this case the defendant had been given planning permission to build a speedway stadium in 1975 and a motorcross stadium in 1992. The defendant had also been issued with a certificate of lawful use under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. However, this was not enough to have changed the rural nature of the area and therefore the level of noise that residents were expected to put up with.

In some cases planning permission may change the nature of the locality. In Gillingham v Borough Council v Medway (Chatham) Dock (1993) (HC) the local council gave planning permission for part of a disused navy dockyard to be used as a commercial dock. This led to a huge increase in traffic with lorries coming and going constantly. A group of local residents brought a claim for (public) nuisance via the council. The court held that in this case the planning permission had changed the nature of the locality from residential to commercial and the residents did not have a claim. The explanation for this decision was that the permission when granted was ‘strategic’ and designed to improve the area for the whole community.

SENSITIVITY OF THE CLAIMANT

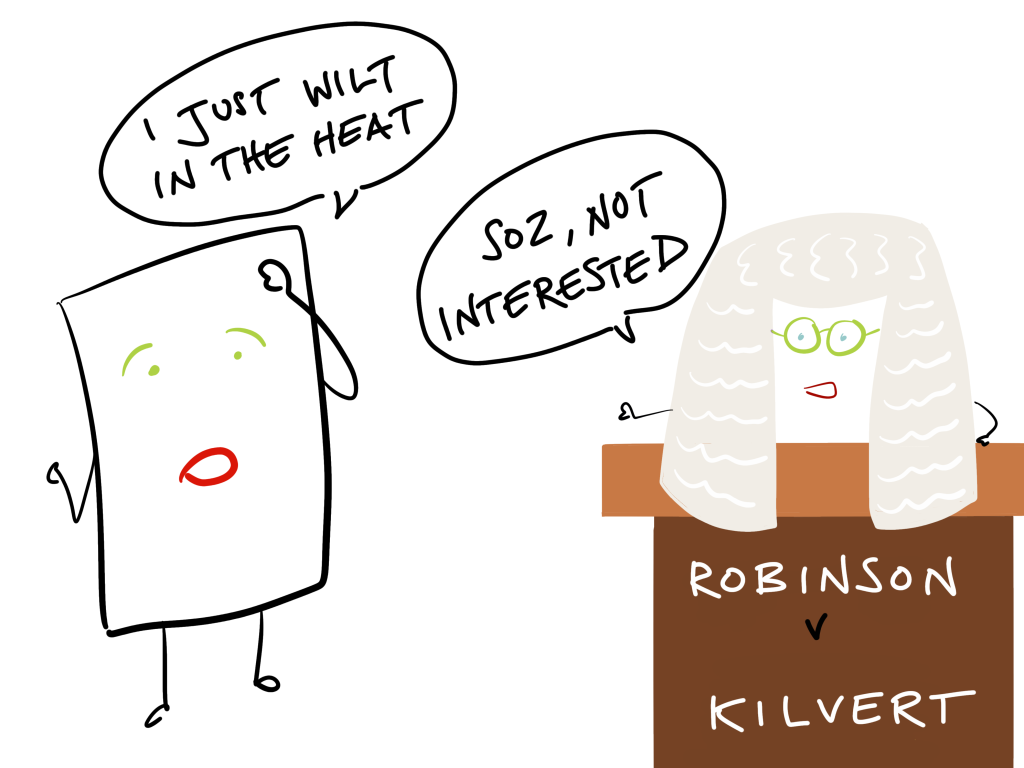

The fact that a claimant may be abnormally sensitive to a certain nuisance will not be taken into consideration (Robinson v Kilvert (1889) (CoA)).

Heat emanating from the manufacturing business in the defendant’s basement caused damage to heat sensitive paper in the claimant’s property above. As normal paper would not have been affected the claimant was not able to claim for their abnormally sensitive paper.

However, if it can be established that the damage would have occurred even if the claimant had not been particularly sensitive then the defendant will be liable for all of the damage. In McKinnon Industries v Walker (1951) (PC) smut and fumes from a neighbouring factory caused damage to plants in a nursery including some orchids. The defendant argued that due to the abnormal sensitivity of orchids he should not be liable for their damage. However, because the nuisance would have caused damage to the orchids even if they had not been sensitive the defendant was liable.

Now this issue is more likely to be dealt with as one of foreseeability rather than sensitivity. In Network Rail v Morris (2004) (CoA) the Network Rail’s new signalling system interfered with Morris’ recording equipment. Network Rail argued that because he was using his equipment for a commercial activity rather than standard recording it was abnormally sensitive. However, the court based their decision in favour of the defendant more on the fact that the damage was not reasonably foreseeable.

MALICE

If it can be shown that the defendant was acting with malice towards the claimant then it will likely be that their behaviour was a nuisance (Christie v Davey (1893) (HC)).

The defendant sent the claimant a letter complaining about the awful noises being made by her children and students when playing musical instruments. The claimant ignored the letter. In retaliation the defendant began making noise by banging on the wall or shouting whenever they could hear music from next door. The claimant sued for nuisance and the defendant counter-claimed but their claim was defeated because they had acted with malice when making the noise.

In Hollywood Silver Fox Farm v Emmett (1936) (HC) the defendant fired off guns near the land boundary between the two parties in order to disturb the foxes on the claimant’s fox farm and stop them breeding. As the noise had been made maliciously the claim succeeded and an injunction was granted. However, if the noise had not been made with malice then the claim may have failed due to the abnormal sensitivity of the foxes.

DEFENCES

The defence of volenti non fugit injuria can be used in cases of nuisance. Claimants can also have their damages reduced based on contributory negligence. However, there are also several defences specific to nuisance.

STATUTORY AUTHORITY

If the defendant was compelled by statute to use their land for a specific purpose which caused the nuisance this will be a complete defence as long as the defendant carried out the activity with due care and the nuisance is an inevitable consequence of the activity (Allen v Gulf Oil Refining (1981) (HoL)).

Local residents brought a claim against the defendant for nuisance caused by noise and vibrations emanating from their oil refinery. The expansion of the existing refinery was authorised by the Gulf Oil Refinement Act 1965. As the Act did not set out specifically how the refinery should be run the court had to decide whether it gave the company implied consent to carry out their activity in the way that was causing a nuisance. By a bare majority they held that it had been and that the defendant had a full defence.

The responsibility for proving this defence and whether the statute gives permission for the activity falls upon the defendant.

Planning permissions or environmental permits are not the equivalent of statutory authority and do no give the defendant a defence. In Barr v Biffa Waste Services (2012) (CoA) the claimants, who lived near a waste disposal site, complained when the site was given permission to dispose of a new kind of waste that caused a bad smell. The first instance decision that the permit meant that the defendant’s activity was automatically reasonable was overturned by the Court of Appeal.

TWENTY YEARS’ PRESCRIPTION

It is also a defence if the defendant can show that the activity complained of has been a nuisance for more than 20 years, during which time the claimant could have brought a claim. The time frame will begin when the landowner became aware of the specific activity that caused the nuisance.

In Sturges v Bridgman (1879) (CoA) the claimant lived next door to a sweet factory which had been there for over twenty years. The claimant was a doctor and decided to build a surgery in his back garden but the noise and vibrations made it impossible to see patients there. He sued for private nuisance and the defendant argued that there was no claim because the factory had been there for over 20 years. The argument was unsuccessful as the claimant had only become aware of the nuisance when he had built his surgery which was less than 20 years ago.

In Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC) the defendant was unable to establish a prescriptive right based on 20 years of activity because he could not prove that the noise from his motor sports stadium had been considered a nuisance for that long, even if he could show that the noise had been generated on a regular basis for over 20 years. The couple who brought the claim had only lived there since 2006 and the previous owner had only complained about the noise to the council in 1992, 16 years before the claim.

The nuisance does not have to be continuous for 20 years. In Carr v Foster (1842) (HC) an absence of two years out of 30 did not destroy a prescriptive right.

COMING TO THE NUISANCE

The defendant, as happened in Sturges v Bridgman (1879) (CoA), may try to argue that the claimant cannot sue for nuisance because they came to the nuisance, i.e. they moved to an area where the defendant’s activity was already established and they should have known better. However, this is not accepted as a defence by the courts. The fact that the claimant came to the nuisance is not sufficient to remove their right to successfully bring a claim (Miller v Jackson (1977) (CoA)).

The claimants moved to a new housing development next to an established cricket club. The club had already built a wall around the ground to stop balls flying into the housing area but this did not stop all balls and the claimants sued for nuisance. The Court of Appeal (Lord Denning dissenting) found that the club’s activity was actionable in nuisance even though the couple had known about the location of the cricket club when they purchased their house. However, they court refused to impose an injunction stopping the club’s activities all together as this would have adversely affected the community, but instead awarded damages.

SOCIAL UTILITY

In some cases the social utility of an activity has been argued as a reason for not classing it as a nuisance but although the court may consider this factor, especially in deciding whether to impose an injunction or not (as in Miller v Jackson (1977) (CoA)) it will not be a defence to nuisance.

The case of Barr v Biffa Waste Services (2012) (CoA) confirmed that social utility can be used when weighing the balance between the claimant and defendant but it should not be given too much weight.

In Adams v Ursell (1913) (HC) the owner of a fish and chip shop located in a residential area tried to argue that the social utility of the shop should stop the smells emanating from the shop from being classed as a nuisance. This argument failed.

The case of Bellew v Irish Cement (1948) (SC of Ireland) illustrates the point even more strongly. The only operational cement factory in Ireland was closed after a nuisance claim was brought against it. Its obvious social utility could not save it.

REMEDIES

Successful claimants can receive damages and/or an injunction, depending on the nature of the nuisance. The court can award an injunction in addition to damages for past nuisance. The claimant can also make the most of the self-remedy of abatement.

INJUNCTIONS

Injunctions are an equitable remedy so are governed by the rules of equity and are discretionary. An injunction is used to stop the defendant from carrying out the activity causing the nuisance. Injunctions can be full or partial, i.e. they could last for a short length of time or only apply to a certain aspect of the activity.

For example, in Kennaway v Thompson (1981) (CoA) the claimant built a house on a lake where speedboat racing took place and brought a claim for nuisance due to the noise of the racing. Rather than award a full injunction the court put in place a partial injunction that confined the racing to certain days and times. In Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC) the injunction applied to activities that created a noise above a certain decibel level.

DAMAGES

Damages are generally sparingly awarded by the courts because otherwise a situation is created in which defendants with money can simply pay to carry on their nuisance. Damages are awarded when an injunction would be inappropriate.

A good example of this is Dennis v Ministry of Defence (2003).

The claimant lived near a military airbase. The noise caused by the aircraft was deemed a nuisance but stopping the aircraft was not possible for national security reasons. Therefore the claimants were awarded £950,000 for the loss in value of their home.

LOSS CONNECTED TO LAND

Damages can be awarded if the claimant can show a loss connected to their land. This is either a fall in value of the land, the cost of repairs or compensation for the claimant’s diminished enjoyment of the land. Lost profits are recoverable but only if they are linked to the claimant’s inability to use the land as normal because of the nuisance. Pure economic loss is not recoverable. It was confirmed in Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997) (HoL) that a claimant cannot claim for personal injury in a private nuisance case.

Damages for property damage are also available. In Halsey v Esso Petroleum (1961) (HC) the claimant received damages for clothes that had been drying in the garden and had been damaged by acidic emanations from the defendant’s oil depot.

INJUNCTION OR DAMAGES?

In Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC) Lord Neuberger set out the current position on remedies in private nuisance. The default position is that a successful claimant will be awarded an injunction unless the defendant can successfully argue that an injunction should not be granted. This is a matter of discretion for the court and a decision should be based on an assessment of all of the facts of the case.

Previously courts become quite restrictive in their granting of damages, only doing so in very exceptional cases and sticking very strictly to the factors as set out by Smith LJ in Shelfer v London Electric Lighting Co (1894) (CoA) to determine whether damages should be awarded in lieu of an injunction.

The factors are;

- If the injury to the claimant is small, and

- if the injury can be estimated in monetary terms, and

- if the injury can be compensated by a small monetary payment, and

- if the granting of an injunction would be oppressive for the defendant, then damages may be awarded in lieu of an injunction.

CRITICISM

This situation was criticised by Lord Neuberger in Coventry v Lawrence (2014) (SC). Judges should use the factors as part of a flexible approach, all circumstances of the case should be considered to arrive at the most appropriate decision. However, if all four factors were satisfied and there were no additional relevant circumstances to consider then damages should probably be awarded, but just because these factors are not satisfied does not mean that automatically an injunction should be granted.

Factors that Lord Neuberger discussed as being appropriate for consideration include;

- planning permission – if permission has been granted specifically for an activity that would possibly cause a nuisance then this can be considered as an argument against granting an injunction,

- the behaviour of the defendant, as an equitable remedy this is important, if they have ‘acted in a high-handed manner’ or tried to ‘evade the jurisdiction of the court’ (Shelfer v London Electric Lighting Co (1894) (CoA)),

- the public interest, this could go either way – if an injunction would cause job loses, or the fact that there are other people who are being affected by the nuisance in the area,

- the proportionate damage done to each party from the granting, or failure to grant, an injunction.

But remember that the starting point is the granting of an injunction and the defendant must successfully argue that damages are a more appropriate remedy.

ABATEMENT

Abatement is a self-help remedy that claimants can pursue to prevent the nuisance without resorting to the courts. This could be used in cases of overhanging branches or other encroachments onto the claimant’s land. Any item that is removed must be left on or returned to the defendant’s land. The claimant can enter onto the defendant’s land to pursue abatement of the nuisance as long as their behaviour is reasonable. Unless it is an emergency the claimant should notify the defendant of their intended action. This action would usually be in lieu of bringing proceedings against the defendant.

WHO CAN SUE?

Only a party with a possessionary or proprietary interest in the land can sue, in other words a landowner, tenant or a grantees of an easement or profit à prendre. Merely occupying or using the land will not be sufficient (Malone v Laskey (1907) (CoA)).

Vibrations from an engine in the adjoining property caused a toilet cistern to fall on a woman. She was unable to make a claim in nuisance because the property belonged to her husband’s employer and she was ‘merely present in the house’.

This was confirmed by the House of Lords in Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997) (HoL) in which some of the claimants were the families of landowners. A family member, visitor, lodger or live-in employee of the landowner will not be able to sue. The rationale behind this is that nuisance is a tort inflicted on land and not any person, hence only someone with an interest in the land can sue.

CRITICISMS

This restriction has been challenged, especially under HRA Article 8, the right to a private and family life. In Khorasandjian v Bush (1993) (CoA) the Court of Appeal allowed the daughter of the landowner to bring a claim in nuisance against her ex-boyfriend who had been making harassing phone calls to the mother’s house. However, this was overruled by Hunter v Canary Wharf (1997) (HoL).

In Mckenna v British Aluminium (2002) (HC) a group of children who lived next door to a noisy and smelly factory sued in nuisance. Neuberger J in the High Court refused to strike out the claim on the basis of a lack of proprietary interest in the land, stating that this would not give proper effect to the meaning of Article 8. However, in Dobson v Thames Water Utilities (2009) (CoA) the children of those with an interest in the land were not awarded any extra damages, it was held that damages awarded to the landowner were sufficient and could be shared with all users of the property, tying the compensation to the land rather than the people on it.

WHO CAN BE SUED?

It is most often the occupier of the land who is sued. However, it is also possible to sue the creator of the nuisance even if they are not the occupier. In Thomas v NUM (1986) (HC) the court allowed a claim against miners who were striking for the nuisance caused by their shouting even though they were not the occupiers of the land.

VICARIOUS LIABILITY

A landowner can be vicariously liable for the nuisance of another if the nuisance was a foreseeable consequence of the third party’s activity and the landowner took no steps to avoid the nuisance. In Matania v National Provincial Bank (1936) (CoA) the claimant had leased a second floor flat from the defendant landlord where he gave singing lessons. The same landlord leased the flat below to a tenant to whom he gave permission to carry out structural alterations. The noise of the work meant that the claimant could not carry out his singing lessons. The landlord knew that the claimant gave lessons in his flat and should have been aware that the building work would disturb this, therefore the landlord rather than the third party was liable.

ADOPTING A NUISANCE

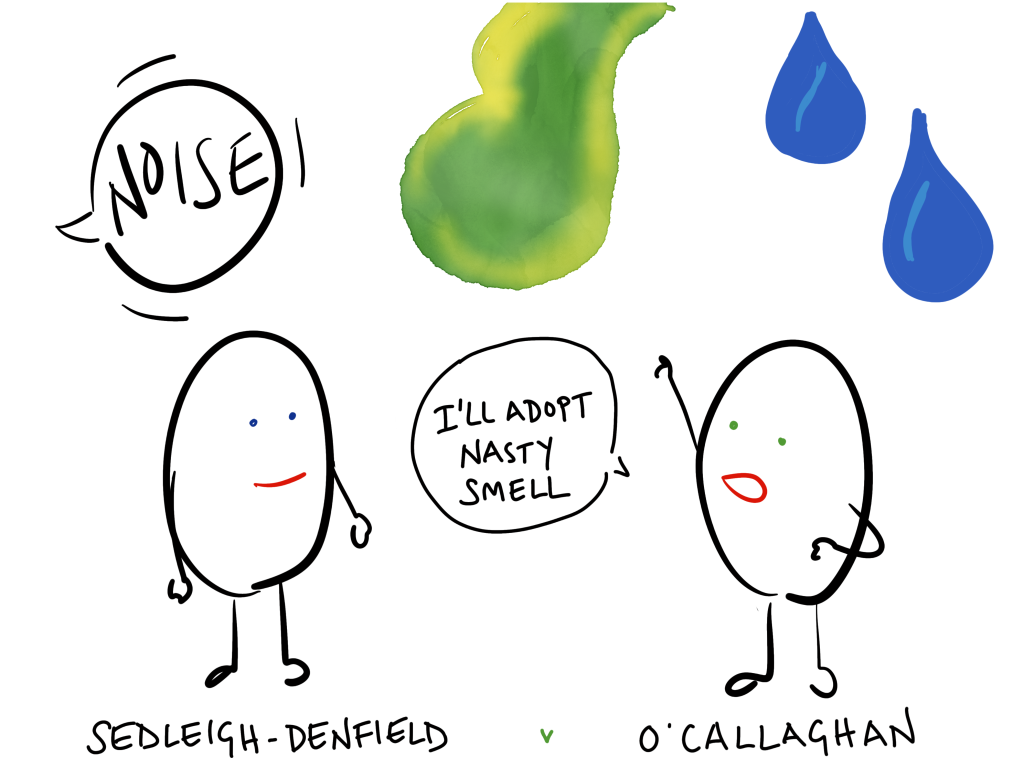

A party can adopt a nuisance even though they did not create it. For example, someone who buys a property with an existing nuisance, or a nuisance caused by a trespasser, which the occupier then continues or fails to abate (Sedleigh-Denfield v O’Callaghan (1940) (HoL)).

The local authority had illegally lain a pipe underneath the defendant’s property. Despite this the defendant continued to use the pipe which leaked onto the claimant’s land. As the defendant had continued to use the pipe he had adopted the nuisance and was liable.

NATURAL NUISANCES

Sometimes a nuisance will not have been caused by the defendant but will have occurred naturally. If the defendant knew of the hazard and failed to do anything about it then they can be liable for the nuisance (Leakey v National Trust (1980) (CoA)).

A mound of earth had built up on the defendant’s land. The defendant knew about the mound and that over time weather conditions had degraded its composition. When the mound collapsed and damaged two houses the defendant was liable.

However, if the level of damage caused by a natural nuisance is beyond what was foreseeable before the event and it would not be fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty of care then the defendant may not be liable. In Holbeck Hall v Scarborough Borough Council (2000) (CoA) the claimant hotel had to be demolished because of a landslip nearby on council owned land. The council had been warned about the erosion of the land and had failed to take any steps to improving it but the extent of the landslip was far beyond what had been foreseen at the time and the cost of preventing it would have been enormous. The defendant was not liable.