JUMP TO: RYLANDS v FLETCHER | BRINGS ONTO LAND | MISCHIEF | ESCAPE | NON-NATURAL USE | FORESEEABLE DAMAGE | DEFENCES | REVISE | TEST

RULE IN RYLANDS v FLETCHER

The rule in Rylands v Flethcher states that when there has been an escape of a dangerous thing in the course of a non-natural use of the land then the defendant will be liable for the damage caused as a result of the escape.

The rule protects land owners from interference with their land from isolated incidents (rather than on-going events) and was first introduced during the Industrial Revolution when there was a proliferation of industries using, and getting rid of, dangerous substances.

The rule is a subsection of nuisance. Although previously considered to exist outside of private or public nuisance the cases of Cambridge Water v Eastern Counties Leather (1994) (HoL) and Transco v Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council (2003) (HoL) confirmed that the rule is part of private nuisance. This means that the claimant must have a proprietary interest in the land and cannot claim for personal injury or pure economic loss.

It is a form of strict liability tort, i.e. liability without fault, so the defendant may be liable even if they have not behaved in a negligent way.

RYLANDS v FLETCHER (1868) (HoL)

Rylands (the original defendant) had built a reservoir on his land to power his mill. Unbeknownst to him there were disused mine shafts underneath the site of the reservoir which connected to Fletcher’s nearby colliery. When the reservoir was filled the water burst into the abandoned mine shafts, travelling along them to Fletcher’s land and flooding his mine. Although Rylands had not acted negligently (he had employed competent engineers to carry out the work) and the event was a one-off rather than a continuing emanation the court found that he was liable for the damage.

The four elements of the rule in Rylands v Fletcher are;

1. the defendant, for his own purposes, brings on his land and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief

2. if it escapes.

3. The defendant must have been engaged in a non-natural use of their land.

4. There be the same element of foreseeability of damage (this factor was added by Cambridge Water v Eastern Counties Leather (1994) (HoL) bringing it more into line with private nuisance).

BRINGS ONTO HIS LAND…

The defendant must have voluntarily brought the item that has caused the damage onto their land (Giles v Walker (1890) (HC)).

Thistles that had seeded onto the claimant’s land from the defendant’s did not fulfil this requirement because the defendant had not actively brought the thistles onto his land.

…ANYTHING LIKELY TO DO MISCHIEF…

The item does not have to be inherently dangerous but must have the potential to cause damage if it escapes. Previous examples include electricity (National telephone v Baker (1893)), part of a fairground ride (Hale v Jennings (1938) (HC)) and acid (Rainham Chemical Works v Belvedere Fish Guano (1921) (HoL)).

HIGH RISK

In the case of Transco v Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council (2003) (HoL) the House of Lords raised the bar and stated that the potential danger caused by an escape must be an ‘exceptionally high risk’ to satisfy this requirement.

In this case a water pipe that carried water through the defendant’s land leaked and over a long period of time caused an earth embankment to collapse which exposed a gas pipe owned by the claimant. The claimant tried to claim the cost of the remedial work under the rule in Rylands v Fletcher but the House of Lords held that the supplying of water to a block of flats was not sufficiently high risk to satisfy the requirement.

ESCAPE

The item that caused the damage must have escaped from the defendant’s land and it must be that item that caused the damage (Read v Lyons (1946) (HoL)).

The claimant was injured when an artillery shell accidentally went off when she was visiting a munitions factory. As she was injured on the defendant’s land it could not be said that the item that caused the damage had escaped, as it had never left the defendant’s property.

EXAMPLES OF ‘ESCAPE’

In Stannard v Gore (2012) (CoA) a pile of tyres on the defendant’s property caught fire. The fire spread and damaged the claimant’s property. A claim under Rylands v Fletcher could not succeed because it was the fire that escaped and not the tyres.

In Transco v Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council (2003) (HoL) the water had not escaped because it had never left the defendant’s land. The effect of the leak exposed the claimant’s pipe that ran across the defendant’s land.

In Rigby v Chief Constable of Northamptonshire (1985) (HC) the police had released CS gas into a property that caused a fire. This was not considered an escape as it had been deliberate.

However, in Crown River Cruises v Kimbolton Fireworks (1996) (HC) fireworks that had been let off deliberately were considered an ‘escape’ because they had not been deliberately aimed at the claimant’s property, they had ‘escaped’ onto the property.

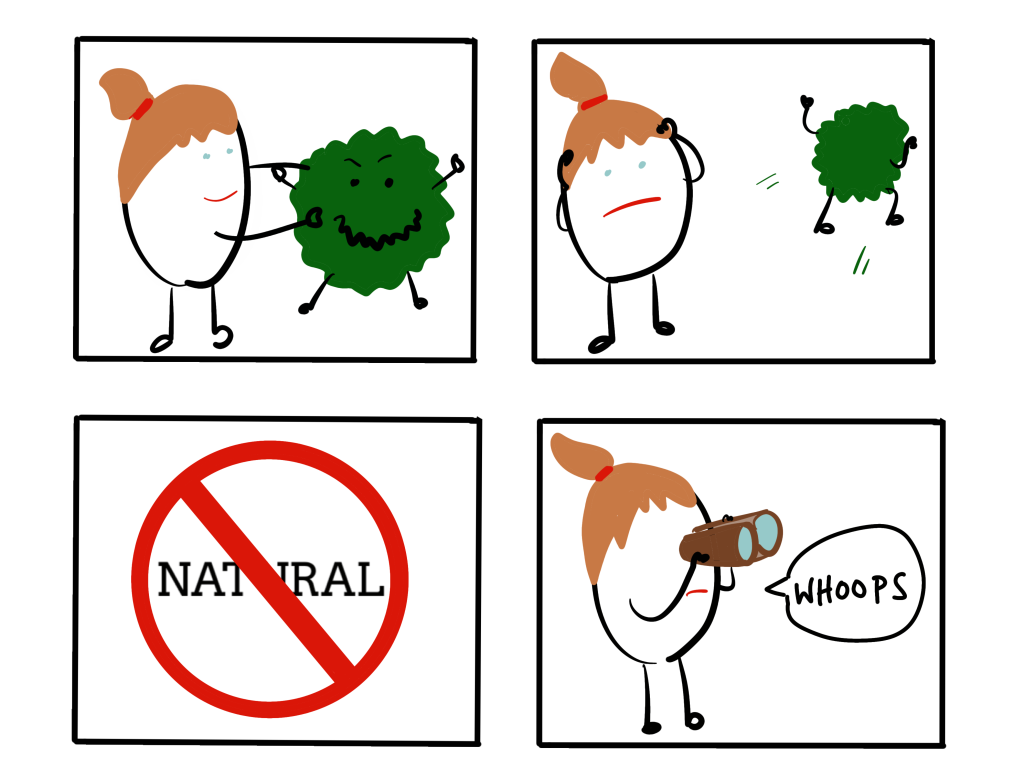

NON-NATURAL USE OF THE LAND

Non-natural use was defined by Lord Moulton in Rickards v Lothian (1913) (PC) as, ‘some special use bringing with it increased danger to others, and must not merely be the ordinary use of land or such use as is proper for the general benefit of the community.’

Rickard’s goods were damaged by a leak from a blocked sink caused by a trespasser in a part of the building leased by the defendant. Unfortunately for Rickards this was deemed a natural use of the land.

Whether a particular use of the land is natural or not will depend on the circumstances of the case and what is normal for the time. For example, in Musgrove v Pandelis (1919) (CoA) storing a car in a garage with a full tank of petrol was an unnatural use, but by Cammidge v Young (1997) this was deemed a natural use.

In Cambridge Water v Eastern Counties Leather (1994) (HoL) chemicals from the defendant’s tanning factory had for many years leaked through the concrete floor, into the land below and ended up in a well several miles away. The claimant had to move the well and they sued the defendant for the cost. The storage of large amounts of chemicals was called ‘an almost classic example of non-natural use’.

As mentioned above in Transco v Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council (2003) (HoL) using a pipe to transport water was a natural use of the land. The link between what is unnatural and what is dangerous was highlighted by the court which suggested that the use should be ‘extraordinary and unusual’ or ‘special’ to qualify as non-natural.

FORESEEABLE DAMAGE OF A RELEVANT TYPE

It is the damage that must be foreseeable rather than the escape itself. If the type of damage was foreseeable then the defendant will be liable for the full extent of the damage.

In Cambridge Water v Eastern Counties Leather (1994) (HoL), although the storing of chemicals was not a natural use of the land the court held that the damage caused by the leaking of the chemicals through the floor, into the earth and then a well was not reasonably foreseeable and therefore not recoverable.

DEFENCES

The defences available are consent or common belief, fault of the claimant, unforeseeable act of a third party, act of God or statutory authority.

CONSENT OR COMMON BENEFIT

The defendant will have a defence if the claimant has consented to the accumulation of the item, or the item was for the benefit of the claimant as well as the defendant.

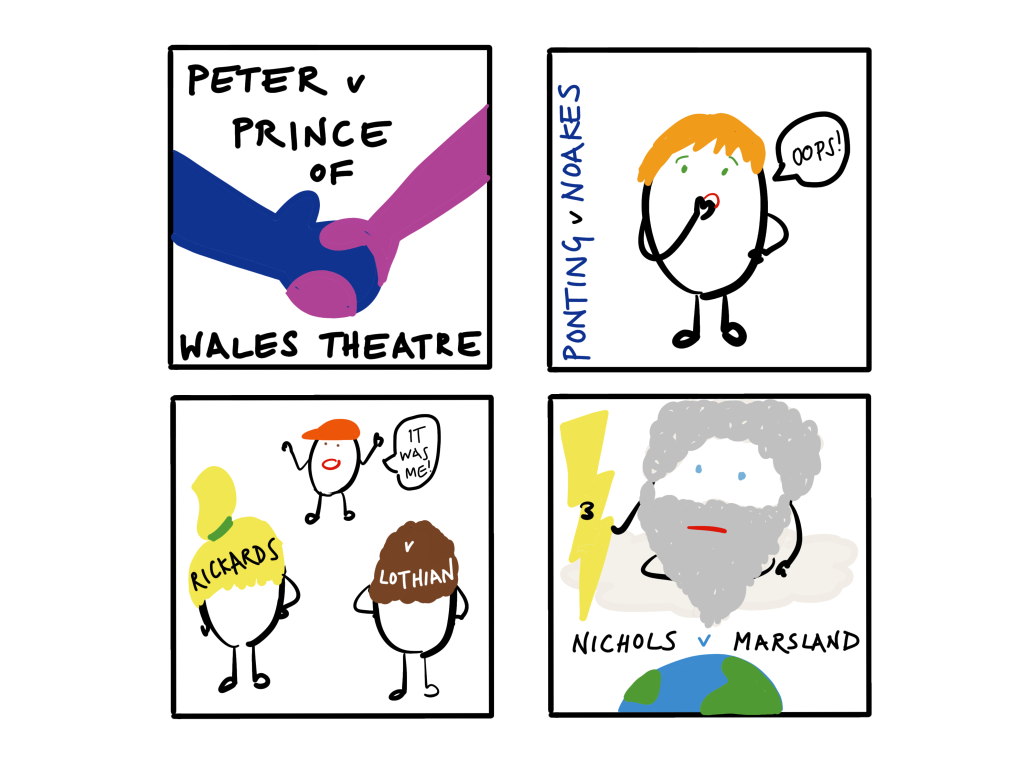

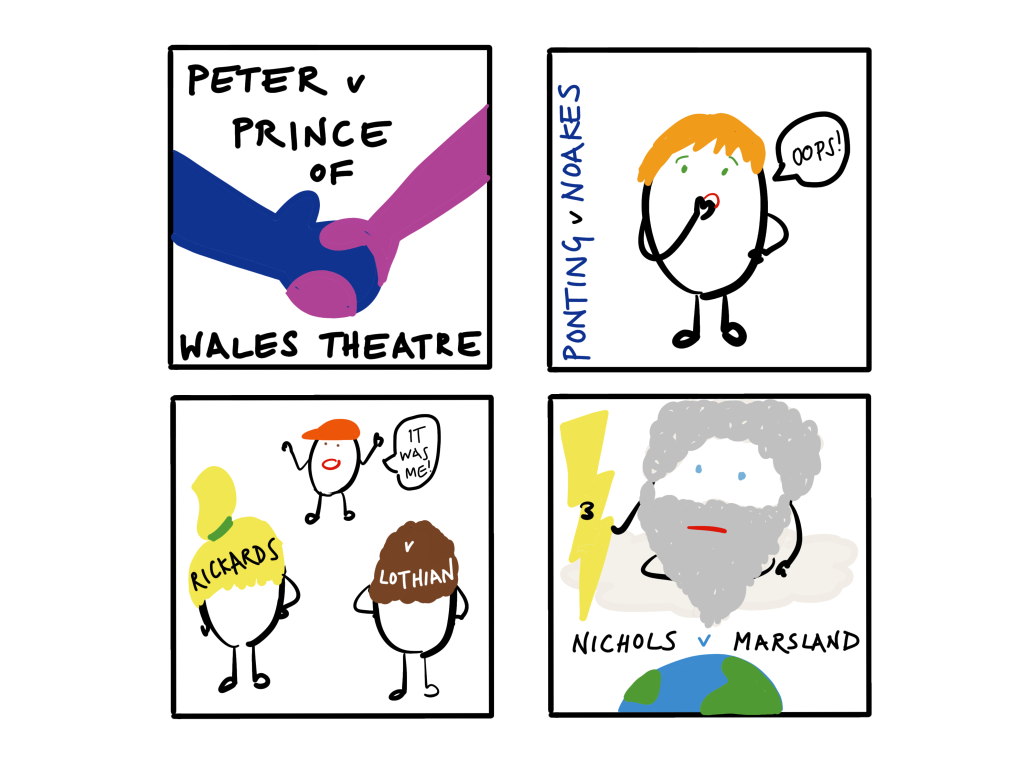

In Peters v Prince of Wales Theatre (1943) (HC) the claimant’s shop was damaged when a pipe for the sprinkler system in the adjacent theatre burst. The defendant argued that not only had the claimant agreed to the installation of the system before leasing the property but the sprinkler system also benefited the claimant. The claim did not succeed.

FAULT OF THE CLAIMANT

If the defendant can show that the escape was in fact caused by claimant there will be no claim. In Ponting v Noakes (1894) (HC) the claimant’s horse died after eating poisonous leaves from the defendant’s land. This was not the fault of the defendant but the horse who lent over the fence to eat the leaves. If the claimant contributed to the escape then the court can apply contributory negligence to apportion liability.

UNFORESEEABLE ACT OF 3RD PARTY

If the escape was caused by the unforeseeable act of a third party and the defendant was in no way negligent then there will be no claim. In Rickards v Lothian (1913) (PC) the fact that the sink was blocked by a trespasser was successfully used as a defence by the defendant.

ACT OF GOD

If the escape was caused by an act of God this will be a defence. In Nichols v Marsland (1876) torrential rain caused ornamental ponds to overflow and flood the claimant’s land. This was an act of God.

STATUTORY AUTHORITY

If the defendant was compelled by statute to use their land for a specific purpose which caused the nuisance this will be a complete defence as long as the defendant has carried out the activity with due care and the nuisance is an inevitable consequence of the activity.

In Allen v Gulf Oil Refining (1981) (HoL) (a public nuisance case) local residents brought a claim against the defendant for nuisance caused by noise and vibrations emanating from their oil refinery. The expansion of the existing refinery was authorised by the Gulf Oil Refinement Act 1965. As the act did not set out specifically how the refinery should be run the court had to decide whether the act gave the company implied consent to carry out their activity in the way that was causing a nuisance. By a bare majority they held that it had been and that the defendant had a full defence.

The responsibility for proving this defence and whether the statute gives permission for the activity falls upon the defendant.

Planning permissions or environmental permits are not the equivalent of statutory authority and do no give the defendant a defence. In Barr v Biffa Waste Services (2012) (CoA) the claimants, who lived near a waste disposal site, complained when the site was given permission to dispose of a new kind of waste that caused a bad smell. The first instance decision that the permit meant that the defendant’s activity was automatically reasonable was overturned by the Court of Appeal.