JUMP TO: ASSAULT | BATTERY | FALSE IMPRISONMENT | DEFENCES | WILKINSON v DOWNTON | REVISE | TEST

TRESPASS TO THE PERSON

There are three main trespasses to the person; Assault, Battery and False Imprisonment. These are actionable per se – which means that a case can be brought even if the claimant suffered no actual damage. It is enough that the act was carried out. They cannot be based on the defendant’s omission or failure to act, they must be based on an action taken by the defendant.

In addition there is the Rule in Wilkinson v Downton (1897) (HC).

ASSAULT

Assault is defined as an act which directly and intentionally causes the claimant a reasonable expectation of immediate and unlawful physical force.

INTENTIONAL ACT

The defendant must have acted voluntarily and their words or conduct must have been direct and intentional.

REASONABLE EXPECTATION

The claimant must have reasonably expected the immediate application of unlawful force. This will be based on what the reasonable man would have expected rather than the claimant.

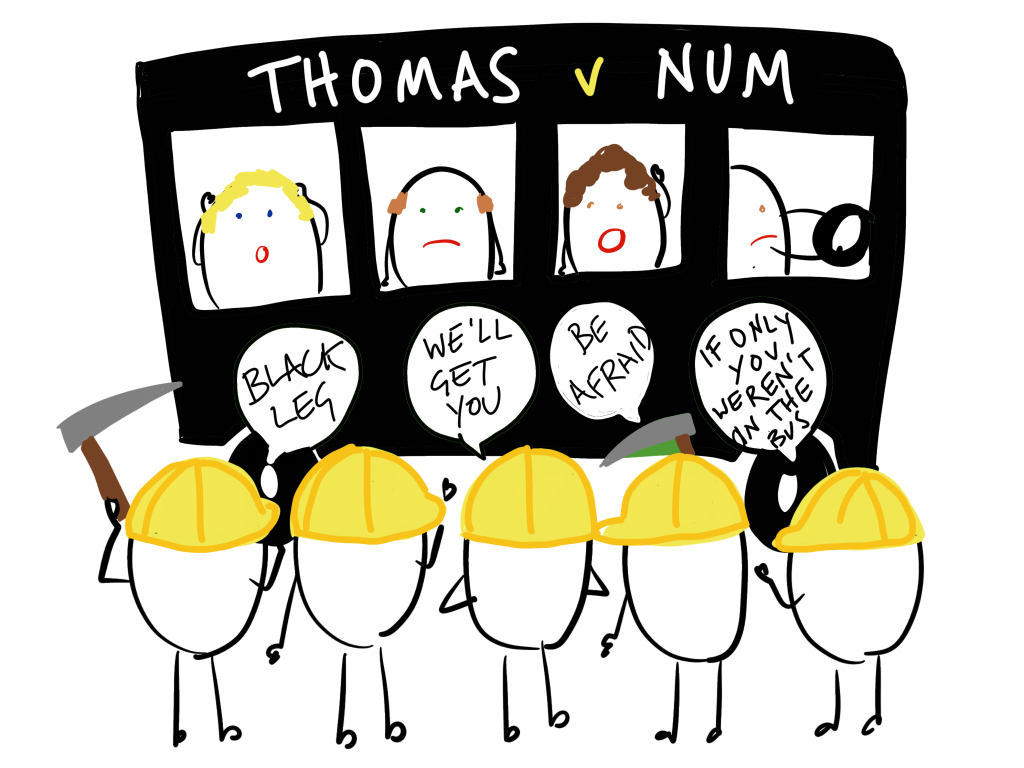

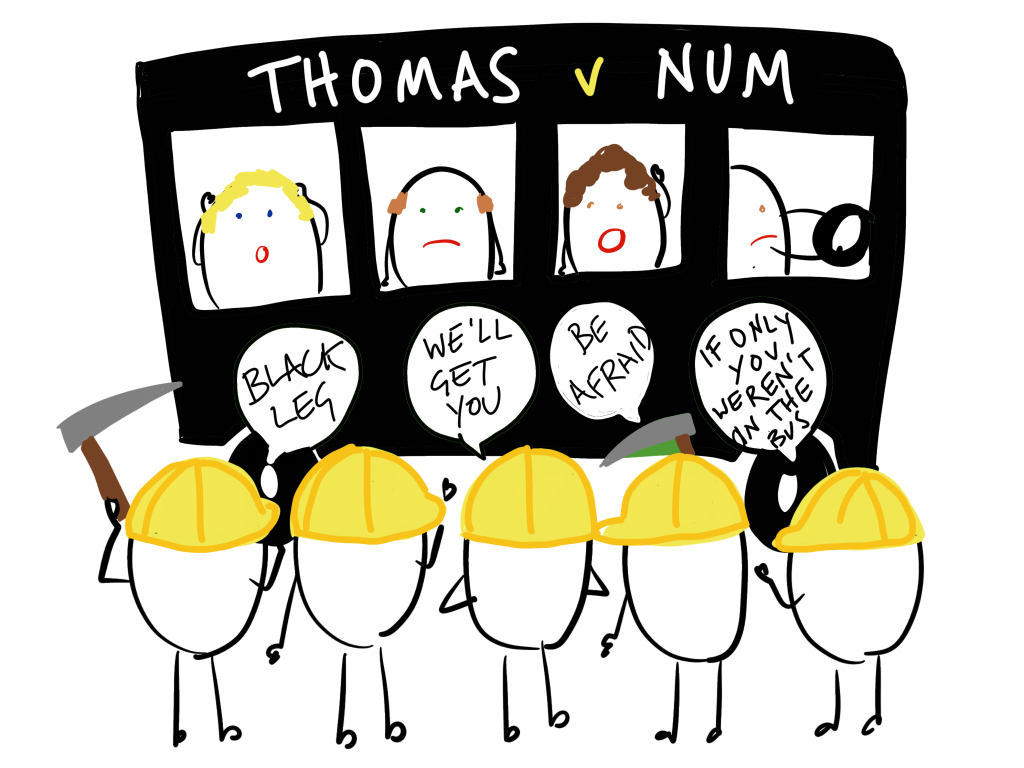

There can be no reasonable expectation if it would have been impossible for the defendant to have carried out the threat at the time it was made (Thomas v NUM (1986) (HC)).

Miners who had ignored a strike were threatened with violence by miners on the picket line. The court held that this was not assault because at the time one group had been inside a bus and the other behind a line of policemen so it would have been physically impossible to carry out the threats.

However, if the claimant believes that the threat could be carried out, even if in reality it could not, they can still have had a reasonable expectation of physical force. For example, being threatened with an unloaded gun that you believe to be loaded.

Also consider Stephens v Myers (1830) (HC) in which a parish council meeting turned ugly when the defendant was asked to leave. He refused and, advancing towards the claimant with raised fists, said he would rather he left instead. He was held back before getting within striking distance of the claimant. The claimant successfully sued for assault. Even though the assailant had been stopped by others it was reasonable for the claimant to have apprehended physical force. However, he was only awarded a small sum to reflect the low level of apprehension experienced.

CONDITIONAL THREAT

If the defendant makes their threat conditional, and not imminent, there can be no reasonable expectation of physical force (Tuberville v Savage (1669) (HC)).

Savage had insulted Tuberville who in response, with his hand on the hilt of his sword, said, ‘if it were not assize time I would not take such language from you’. In doing so he admitted that he would not carry out the threat at that moment and therefore Savage could not reasonably expect physical force.

WORDS AND GESTURES

It is possible for words, gestures or even silence to constitute assault if the claimant can be said to have been in immediate fear of physical force.

In R v Ireland (1998) (CoA) several women had been subject to an extended campaign of harassment by the defendant which included silent telephone calls. The court held that this could amount to assault if the victim reasonably expected an imminent act of physical force.

BATTERY

Battery is defined as a direct and intentional application of force without lawful justification.

DIRECT

The application of force must be direct. The classic example of this, stated in Reynolds v Clarke (1725) (HC), is that of someone throwing a log onto a road. If it hits someone when thrown that is a direct act, if someone later trips over the log that would be an indirect act. The former would be trespass to the person, the later a case of negligence.

SHORT DELAY

However, the courts have been flexible with the concept of directness if there is a limited amount of time between the act and the application of force. In Scott v Shepherd (1771) (HC) the defendant threw a lit squib into a crowded market place. Before it hit the claimant it was thrown onward by several market traders. Despite this it still counted as Shepherd’s direct act.

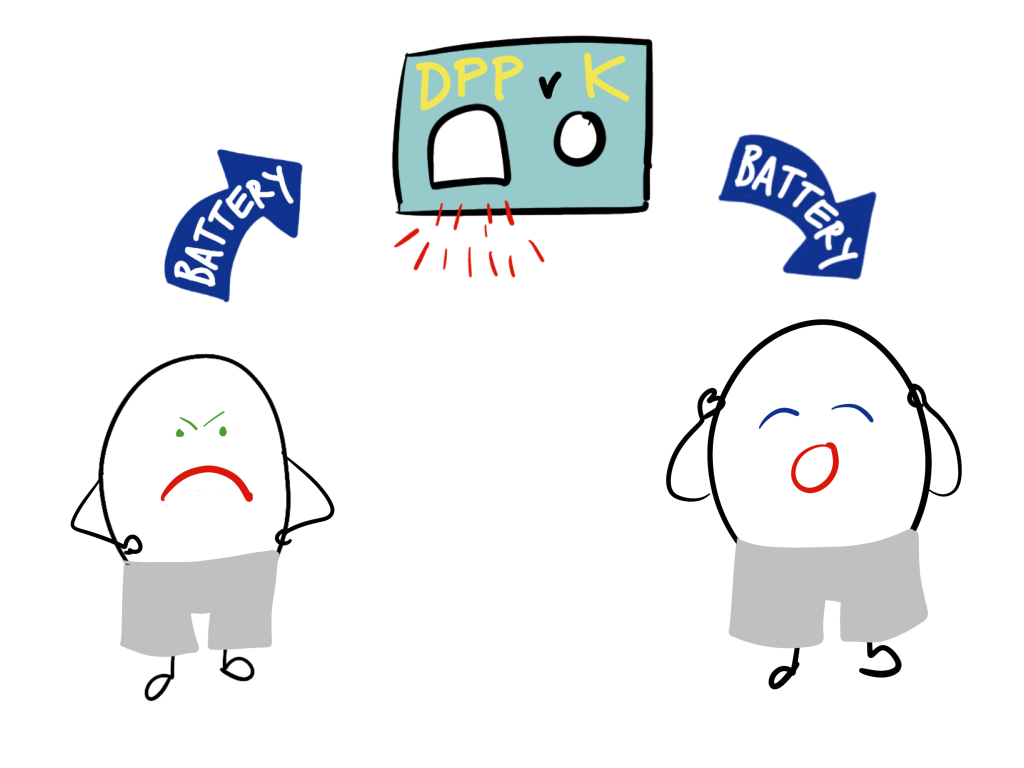

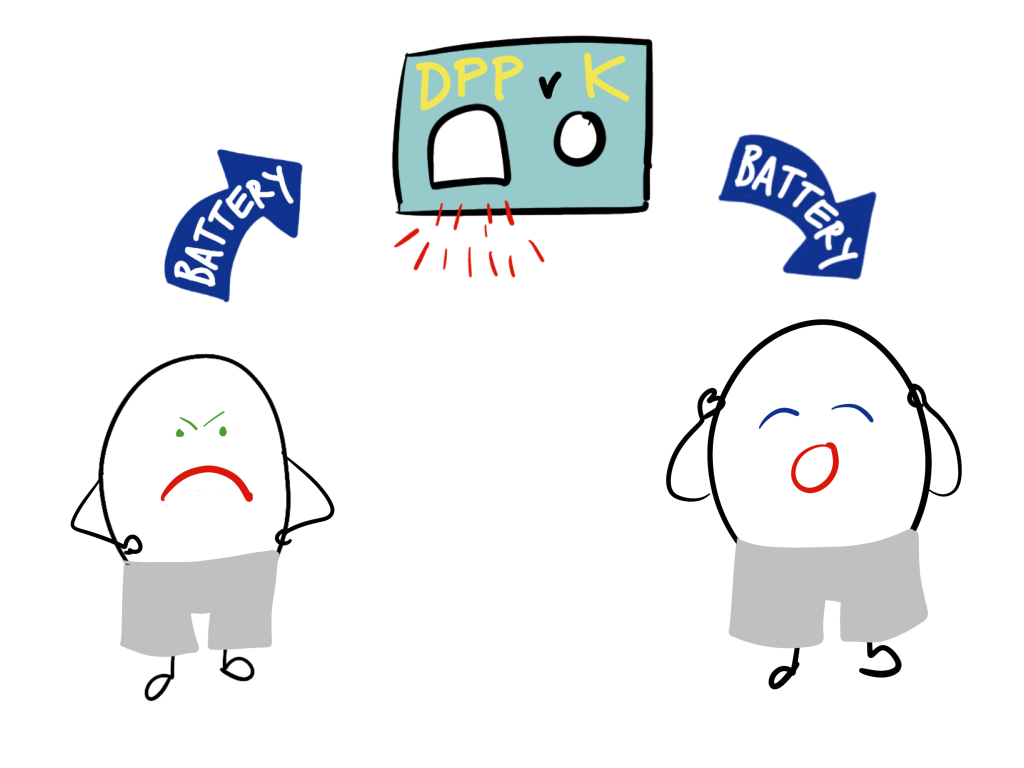

The more modern case of DPP v K (1990) (HC) also illustrates this point.

A schoolboy put sulphuric acid into an upturned hand dryer. Shortly after another boy used the hand dryer and was burnt by the acid. This was held to be sufficiently direct.

INTENTIONAL

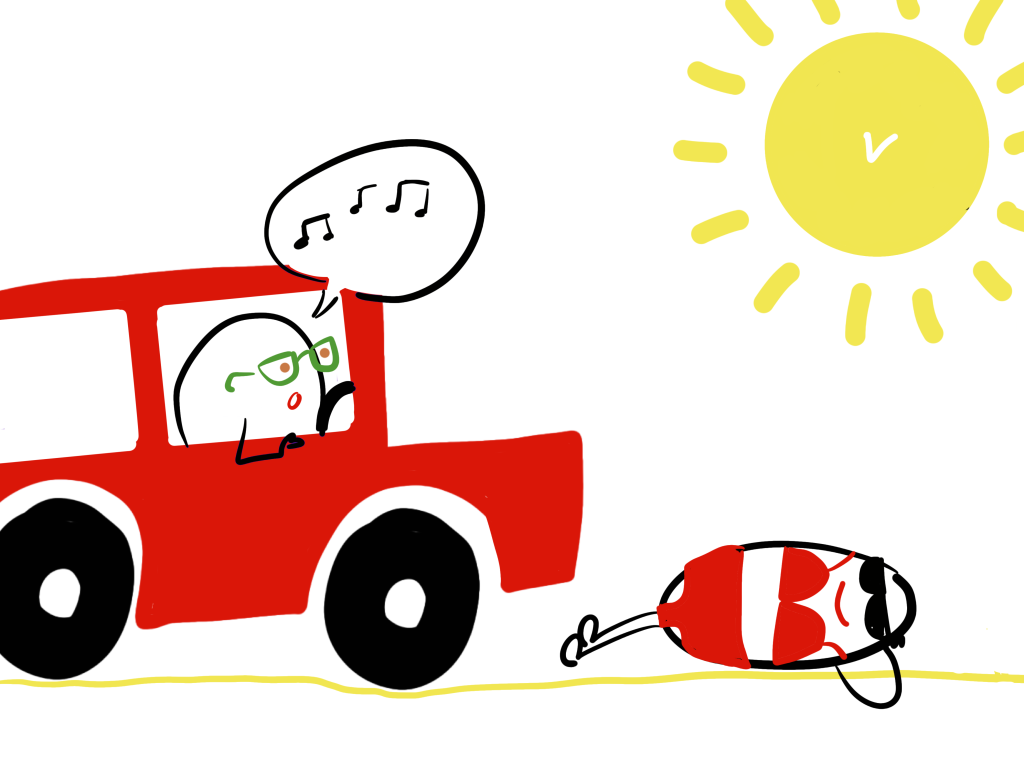

The act must be intentional. The defendant need not have intended to cause harm but the application of force must have been either intentional or reckless (Letang v Cooper (1965) (CoA)).

Mrs Letang was sunbathing on a patch of grass in front of Mr Cooper’s car. Not knowing she was there he drove his car over her legs. As this act had been carried out unintentionally Mrs Letang could not bring a case under trespass to the person.

Mrs Letang could not bring a case in negligence either because the limitation period had expired.

TRANSFERRED INTENT

If Cooper had intended to drive over another sunbather’s legs but instead ran over Mrs Letang he would still have been liable for battery even though he had intended to apply force to a different person. This is called ‘transferred intent’. In Livingstone v Ministry of Defence (1984) (HC) a soldier who had been sent to control a riot shot Livingstone with a rubber bullet. Even though he had been aiming at someone else the court held that he could still be liable for battery against Livingstone based on the theory of transferred intent.

ACT NOT OMISSION

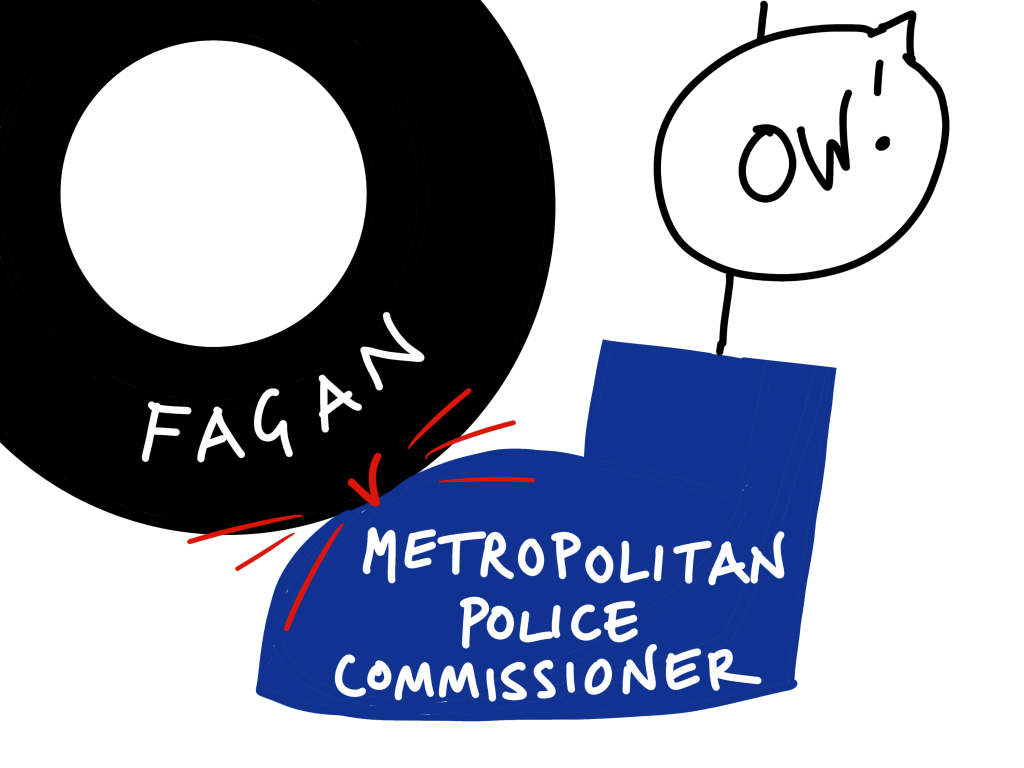

The defendant must have carried out an act, there can be no battery by omission. This was discussed in Fagan v MPC (1969) (Divisional Court).

A man accidentally drove onto a policeman’s foot but then refused to move his car. He argued that not moving the car was an omission, and therefore not a direct act, but the court held that it was an act as he had made a positive decision not to move the car.

This also shows that what was an unintentional act (driving onto the foot) can become intentional (refusing to move).

APPLICATION OF FORCE

In theory any application of force can equal battery. In Cole v Turner (1704) (HC) it was stated that, ‘the least touching of another in anger is a battery’.

In R v Cotesworth (1704) (CoA) spitting in a doctor’s face was application of force.

HOSTILITY

There is debate about whether an element of ‘anger’ or ‘hostility’ in an application of force is necessary for battery. In Wilson v Pringle (1987) (HC) the court had to decide if a school boy who had injured a fellow pupil in an act of horseplay had performed a battery. The court held that there had been no battery because there was a lack of hostility. Hostility will be a question of fact decided by the judge.

However, it has been argued that adding the need for hostility is too difficult to define and too restrictive. For example, a doctor who mistakenly performs surgery on a patient without their consent will have performed a battery but without any hostility.

In Collins v Wilcock (1984) Goff LJ suggested a different test; that touching will not be a battery if it could be considered ‘generally acceptable in the ordinary conduct of daily life’ and therefore either explicitly or impliedly consented to by the claimant. For example if you go shopping on Oxford Street and someone bumps into you this would not be a battery because by placing yourself on the busiest street in London you has consented to a certain level of force being applied by other pedestrians.

DEFENCES

An act will only be an assault or battery if there was no legal justification for it. If the defendant can show that they acted with the claimant’s consent, out of necessity or in self-defence then they will have acted legally.

EXPRESS CONSENT

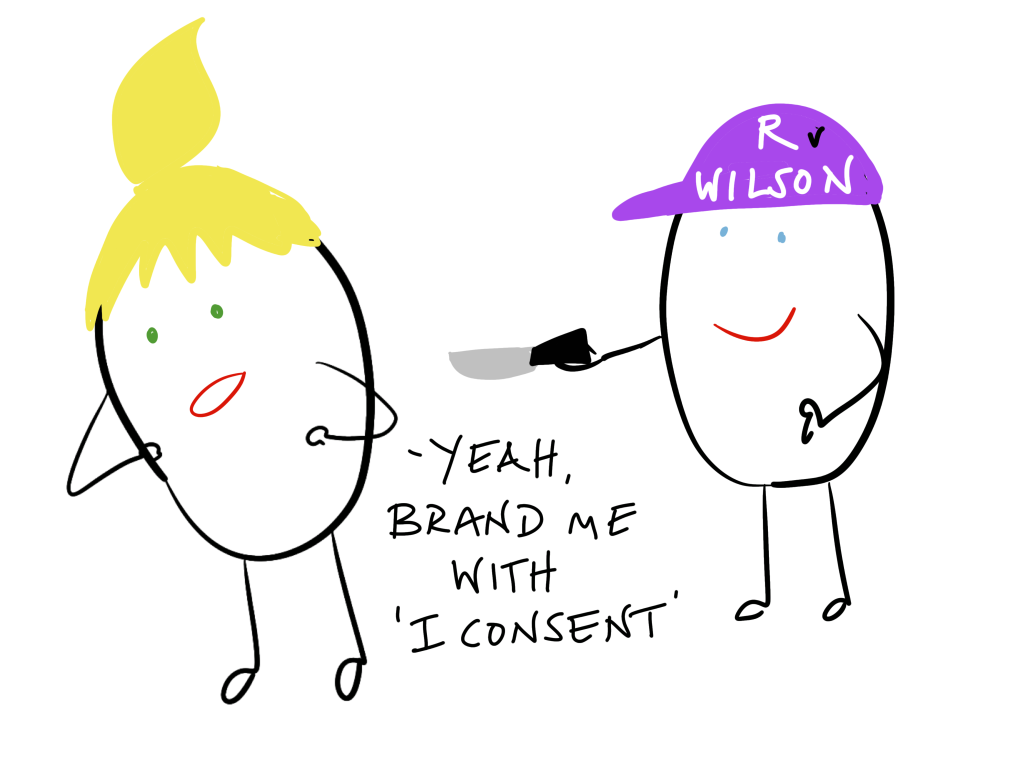

If the claimant consented to the battery then it will have been legally justifiable. A claimant can have consented to any battery that does not result in harm equalling GBH or worse (R v Wilson (1996) (CoA)).

A woman asked her husband to brand his initials onto her buttock with a hot knife. When the wound became infected he was charged with ABH. However, she had consented to the act so it was legally justifiable.

Also consider R v Brown (1993) (HoL) in which the group of defendants could not use consent as a defence. The harm that they had inflicted upon each other during homosexual sadomasochistic activities had been too severe. This was for public policy reasons, the judges did not want to encourage others to engage in what they described as ‘depraved’ activity. Two out of the five judges were dissenting and it has been argued that these policy concerns would not be argued today.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Any invasive medical treatment carried out without the consent of the patient will be a trespass to the person. If it is not possible for the patient to give their informed consent then medical staff must do what is in the best interests of the patient. In F v West Berkshire Health Authority (1989) (CoA) the patient, although an adult, had the mental capacity of a minor. Her parents sought guidance from the court as to whether she could undergo sterilisation without giving informed consent. In this case the court agreed that it was in the patient’s best interest and the procedure could go ahead without her consent.

IMPLIED CONSENT

As discussed above a claimant could have given implied consent to a battery (see Collins v Wilcock (1984) (HC) above). For example, it is assumed that claimants involved in sports have given their implied consent to batteries inflicted whilst playing sport as long as the rules of the game were adhered to and there was no negligent act that led to the injury.

SELF DEFENCE

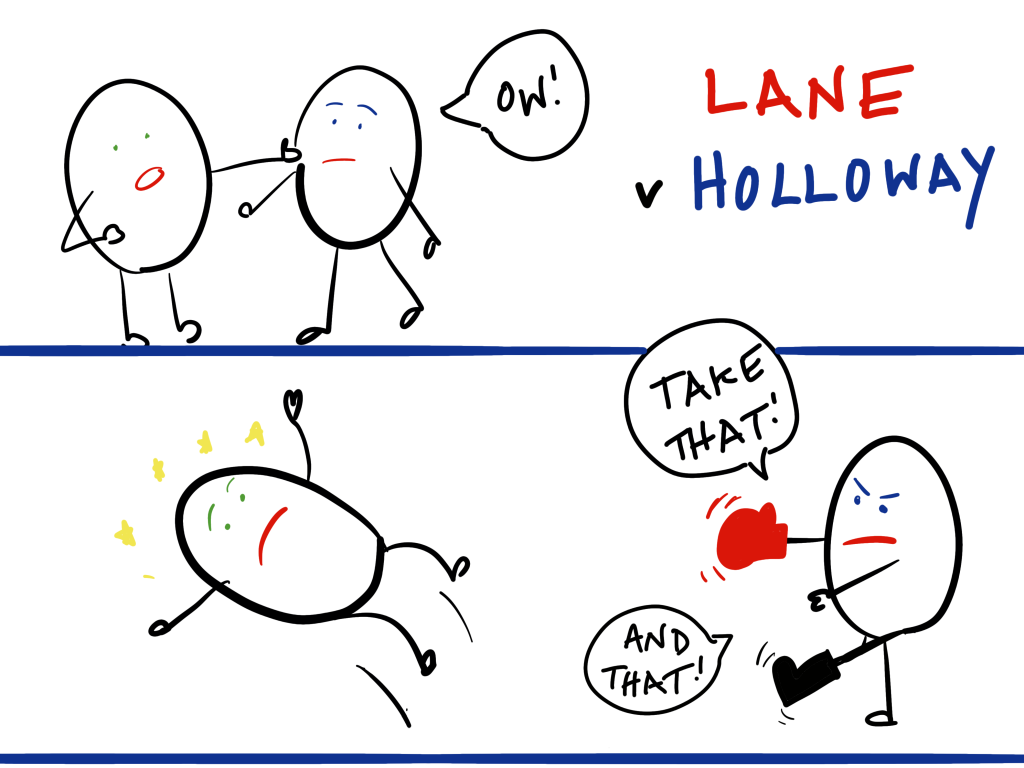

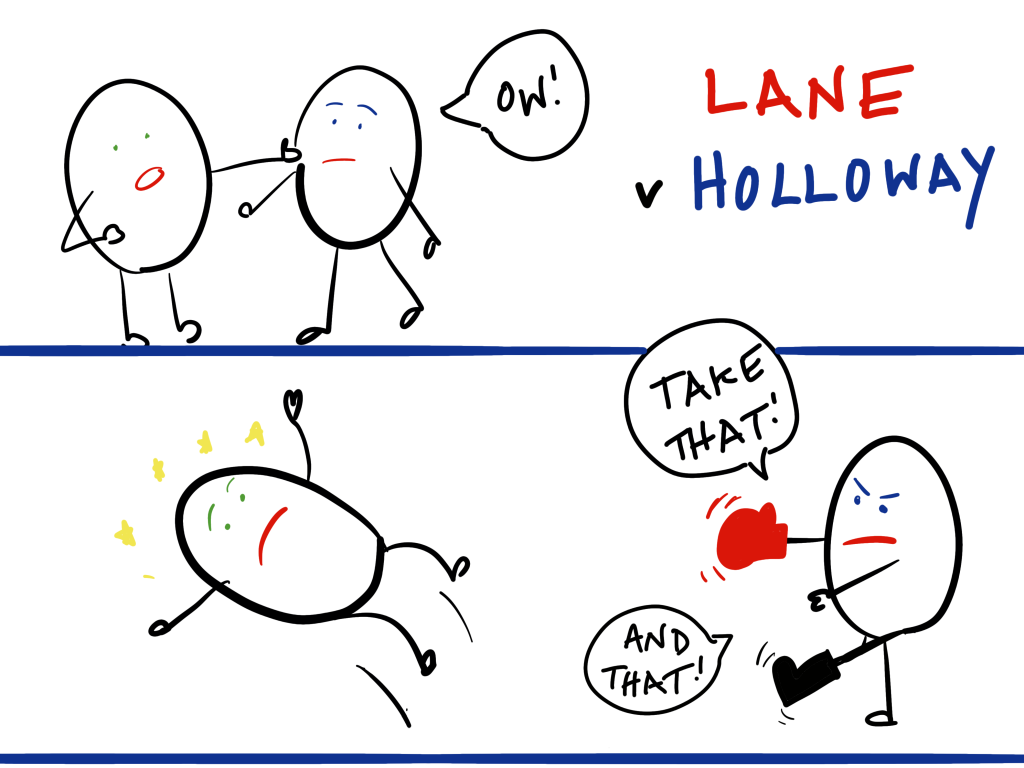

A defendant can plead that their application of force was self defence. Their response must have been reasonable and proportionate to defend themselves, protect another person or protect property. What is reasonable will rest on the facts of the case (Lane v Holloway (1968) (CoA)).

Lane lived next to Holloway’s pub and relations were bad between the two neighbours. One evening when people in the pub garden were being noisy Lane went to complain and ended up shouting at Holloway’s wife calling her a ‘monkey-faced tart’. When Holloway approached Lane he feared that Holloway would hit him so pushed him on the shoulder. In response Holloway punched Lane in the eye leading to an injury that needed stitches. Even though they had both been involved in the fight Holloway’s reaction had been out of all proportion and therefore could not be self defence. The difference in age between the two men contributed to the response being out of proportion to the provocation.

The defendant also tried to use the defence of illegality and consent. Neither of these were accepted. Two people in a fight can consent to incidental injuries but not injuries out of proportion to the provocation.

Also consider Ashley v Chief Constable of Police (2008) (HoL) in which an unarmed man was shot dead in his bed by a police officer during a police raid. The officer admitted negligence but claimed that he had acted in self defence, this was rejected by the court. The court emphasised the difference between the test in crime and tort; in crime the fear of attack does not have to be reasonably held but it tort it must be reasonable.

NECESSITY

Necessity can be a defence. For example in cases of medical emergencies where the claimant is unconscious the defendant may have carried out a medical procedure on them without their consent. If this was necessary for the best interests of the claimant it will not be a trespass to the person. In Airedale NHS Trust v Bland (1993) (HoL) the patient had been in a coma for several years after being injured in the Hillsborough disaster. The court held that, without any chance of improvement in his condition, it was in the patient’s best interests not to prolong life and his life support machine could be turned off without his consent.

FALSE IMPRISONMENT

False imprisonment is defined as an illegal and intentional complete restriction of the claimant’s freedom of movement.

INTENTIONAL

As with the other trespasses to the person the act must be intentional, or reckless as to the consequences of the act. The imprisonment must be a direct act, it cannot be an omission or accidental.

In Sayers v Harlow Urban District Council (1958) (CoA) Sayers became trapped in a public toilet when the lock stuck. This was a case of negligence rather than false imprisonment as her imprisonment had not been the consequence of any intentional act by the defendant.

Also see Iqbal v Prison Officers Association (2009) (CoA) in which a prisoner was denied his normal length of time outside his cell because of a prison officer strike. Not opening the cell was held by the majority to be an omission rather than an act. Only one dissenting judge held that the strike itself was the act that had led to the false imprisonment.

COMPLETE RESTRICTION

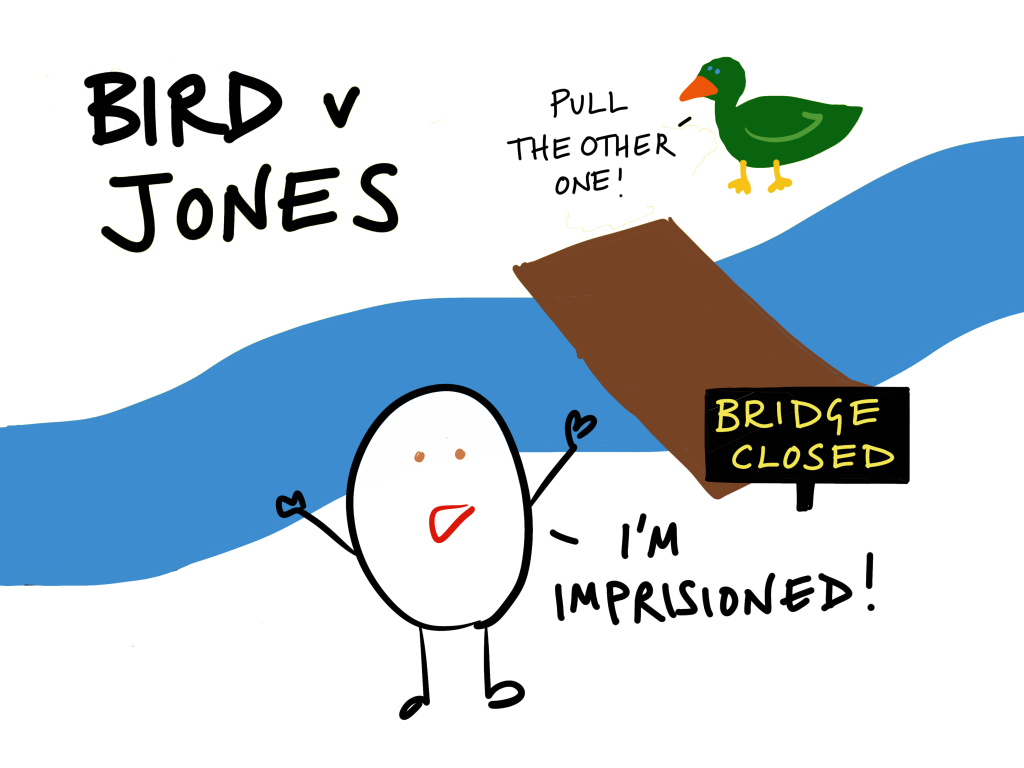

There must be a complete restriction of the claimant’s freedom of movement (Bird v Jones (1845) (HC)).

Seating had been erected on the banks of the Thames that restricted the use of the public footpath across Hammersmith Bridge. When he could not use the footpath to cross the bridge Bird claimed he had been falsely imprisoned on one side of the river. The fact that he was able to go back the way he had come meant that his freedom of movement had not been completely restricted and he had not been falsely imprisoned.

In R (on the application of Jalloh) v Secretary of State for the Home Dept (2020) (SC), Jalloh was made to adhere to a curfew and wear an electronic tag for 891 days. The court held that because the Secretary of State had no power to impose this curfew Jalloh had been falsely imprisoned. Even though there had been no physical barrier stopping him from moving his freedom had been completely restrained without legal justification.

TIME

As long as the restriction of freedom of movement is complete it does not matter how long it was for. In Walker v The Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis (2014) (CoA) the claimant, before his arrest, had been restricted by a police office for a few seconds in a narrow doorway. The court held that he had been falsely imprisoned but displayed their dislike of the case by only awarding him £5 in damages.

Arrest and detention, if carried out legally, will not be false imprisonment, although being held after the conditions for a legal detention have ended will be (Roberts v Chief Constable of Cheshire (1999) (CoA)).

CONDITIONAL RESTRICTIONS

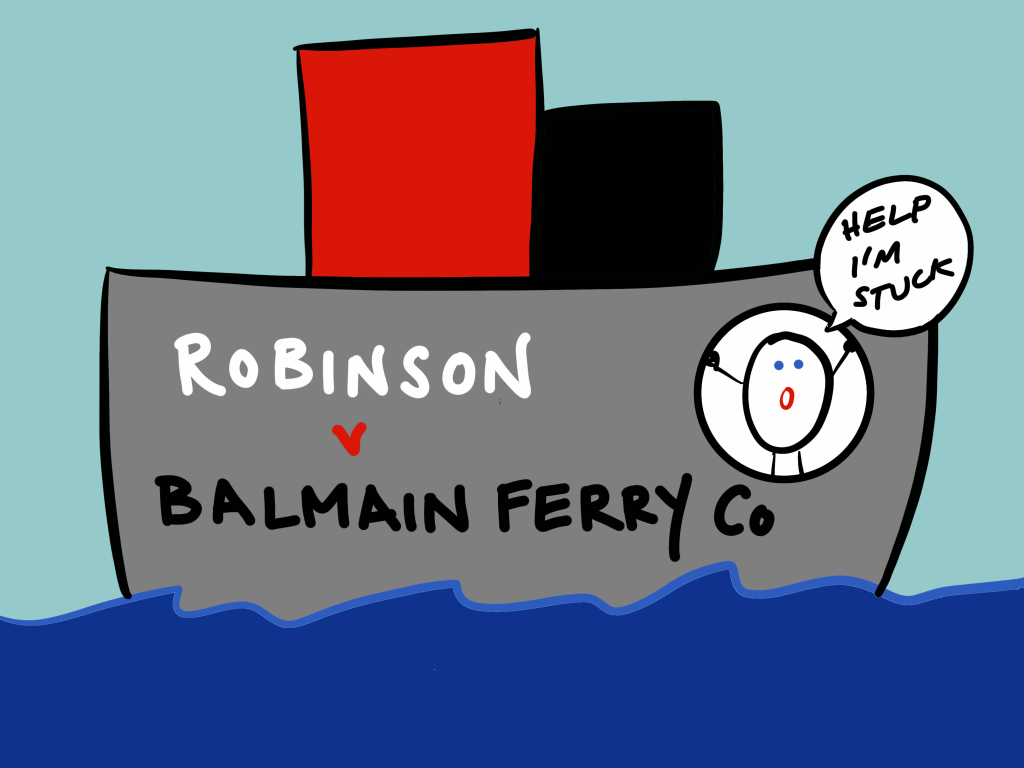

If someone’s freedom of movement is restricted by certain conditions, but these conditions are deemed to be reasonable, it will not be false imprisonment (Robinson v Balmain Ferry Co (1910) (PC of Australia)).

Robinson bought a ferry ticket on the understanding that he would have to pay again to exit the ferry terminal on the other side. After passing through the entrance gates he changed his mind and wanted to leave the terminal without taking the ferry. The company requested that he pay the fee which he would have had to pay when exiting on the other side. He refused. Robinson claimed false imprisonment but the court held that the conditions imposed by the company were reasonable and known to Robinson before he bought his ticket. Therefore he had not been falsely imprisoned.

In Herd v Weardale Steel, Coal & Coke (1915) a miner wanted to be brought up from the mine before his shift was over but was refused. When he sued for false imprisonment the court held that it was not false imprisonment to be held to the terms of a contract that he had agreed to.

UNKNOWINGLY IMPRISONED

The claimant need not be aware that they have been falsely imprisoned. In Meering v Grahame-White Aviation (1919) (HoL) the claimant sat in an office for hours unaware that he was unable to leave. He had still been falsely imprisoned.

WORDS

Words can equal false imprisonment, for example ‘stay where you are or I’ll kill you’ (Davidson v Chief Constable of North Wales (1994)) (CoA).

RULE IN WILKINSON v DOWNTON

There is another category that is not technically a trespass to the person but the intentional infliction of mental shock, known as the rule in Wilkinson v Downton (1897) (HC). The defendant must have wilfully done an act calculated to cause physical harm to the claimant and the claimant did suffer physical harm.

Mr & Mrs Wilkinson ran a pub. One day whilst Mr Wilkinson was away at the races and Mrs Wilkinson was running the pub one of the regular customer, Downton, played a practical joke on her. He told her that her husband had been involved in an accident and had suffered two broken legs and was now lying at The Elms pub and that she must go there to bring him home. On hearing this news she suffered severe nervous shock and distress; she vomited and her hair turned grey. She continued to suffer for weeks. The defendant was not liable for assault or battery but for intentional infliction of mental shock

The rule was upheld in Janvier v Sweeney (1919) (CoA). Sweeney was a private detective who sent his assistant to obtain information from Janvier. In order to do this he pretended to be a policeman and told Janvier that she was wanted for communicating with a German spy. In fact she had been communicating with her German lover who was interned in a British prisoner of war camp. She suffered nervous shock and was awarded damages based on the rule in Wilkinson v Downton.

PSYCHIATRIC HARM

As well as physical harm a defendant can also be liable for any recognised psychiatric illness (Wong v Parkside Health (2003)).

Wong had been bullied by her colleagues and tried to claim under the Rule in Wilkinson v Downton. The court held that their behaviour had been rude and unfriendly but had not been intended to cause physical (or psychological) harm. Although Wong was unsuccessful the court did recognise that a claim could be based on psychiatric as well as physical harm.

JUSTIFICATION

There must be no justification or reasonable excuse for the acts or words. Recklessness as to the effect of the act is not sufficient (Rhodes v OPO (2015) (SC)).

A son could not use the rule in Wilkinson v Downton to stop his father publishing an autobiography including details of abuse the father had suffered as a child. The son, who suffered from many special educational needs, argued that publication of the book would cause him harm. The court rejected the case; publication could be justified and was not intended to cause harm.