JUMP TO: VICARIOUS LIABILITY | PRIMARY LIABILITY | STANDARD | BREACH | INFORMING OF RISK | FACTUAL CAUSATION | LEGAL CAUSATION | REVISE | TEST

CLINICAL NEGLIGENCE

Professional negligence covers the duty owed by all professionals to their clients. The elements of a negligence claim are the same as for a non-professional but the standard to which that professional is held will depend on the defendant and the facts of the case. Clinical negligence is an area of professional negligence that covers all medical professionals including dentists, paramedics, physiotherapists, etc.

VICARIOUS LIABILITY

It was established in Cassidy v Ministry of Health (1951) (CoA) that medical professionals and their employers owe patients a duty of care. This is usually a case of vicarious liability. As stated by Lord Denning, ‘whenever they accept a patient for treatment, they must use reasonable care and skill to cure him of his ailment. The hospital authorities cannot, of course, do it by themselves: they have no ears to listen through the stethoscope, and no hands to hold the surgeon’s knife. They must do it by the staff which they employ; and if their staff are negligent in giving the treatment, they are just as liable for that negligence as is anyone else who employs others to do his duties for him.’

If a patient enters a hospital in an emergency the hospital owes a duty of care even if a member of staff only gives the patient advice and tells them to go home. To avoid any duty of care the hospital would have to close its doors and not admit anyone (Barnett v Chelsea & Kensington HMC (1969) (HC)).

A man became ill after ingesting arsenic. When he arrived at hospital feeling unwell he was not examined by the doctor but told to go home and see his GP. He later died as a result of the poisoning. The hospital had a duty of care for the claimant even though they had not given him any treatment. However, the hospital was not liable because it was proved that even if they had treated him he would still have died from the poisoning.

Since the case of Darnley v Croydon Health Services NHS Trust (2018) (SC) hospitals can also be vicariously liable for the actions of non-medical staff such as receptionists. The claimant suffered a head injury. At A&E he was given incorrect information by an A&E receptionist about waiting times. Believing that he would have to wait 5 hours he left the hospital without seeing a doctor about his head injury. When his condition worsened later that day he was taken to hospital but suffered permanent brain damage. The hospital owed him a duty of care to provide accurate information which they had breached.

PRIMARY LIABILITY

Health authorities can also owe a direct, primary duty of care to patients. For example, a duty to employ staff of a sufficient skill level. In Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority (1998) (HoL) it was argued that the hospital had failed in this duty by providing an inexperienced junior doctor to care for a premature baby.

However, this is not an absolute duty. For example, a health authority is not obligated to provide all available treatments. It is reasonable to take factors beyond the health of the patient, such as cost, into account when deciding how to treat them (R v Cambridge HA, ex parte B (1995) (CoA)). A child who was dying of leukaemia was refused treatment that would have cost £75,000 with only a 10-20% chance of working. This was not a breach of the hospital’s duty.

STANDARD

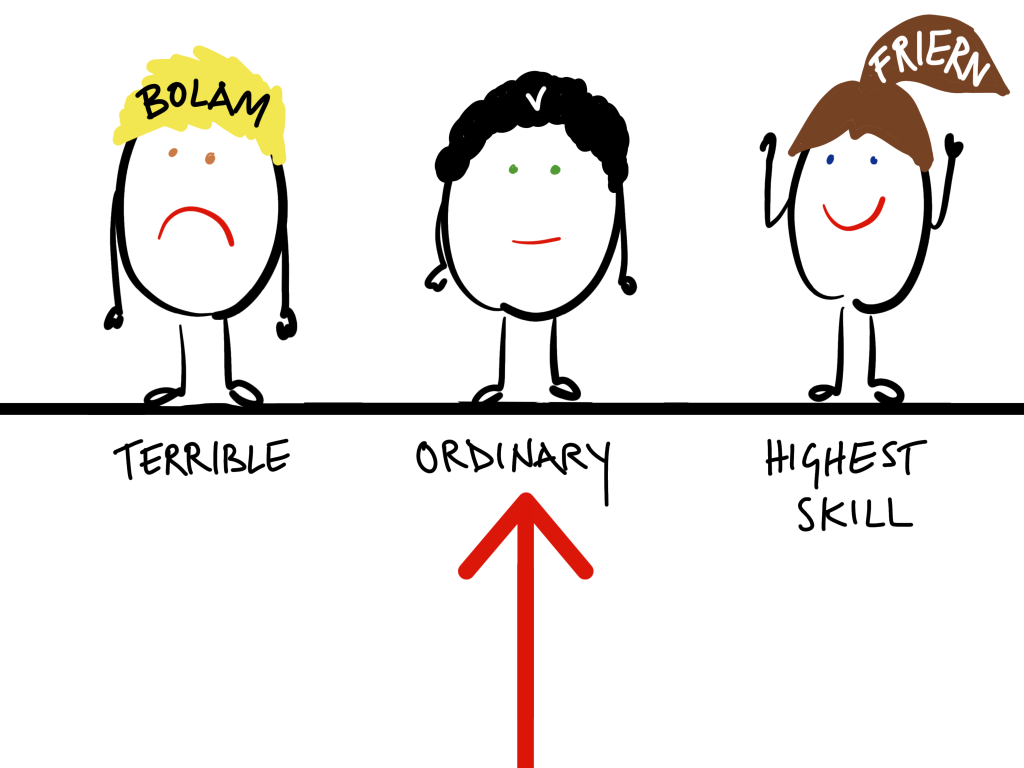

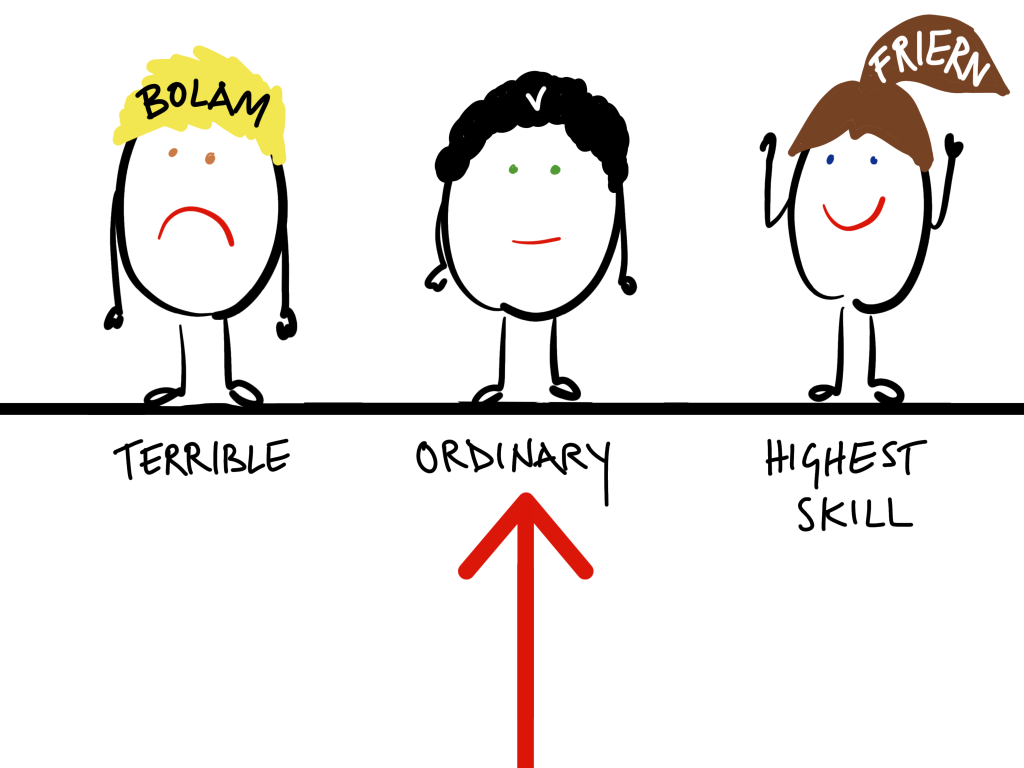

The test for what standard a professional should be held to was set out by McNair J in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) (HC).

‘The test is the standard of the ordinary reasonable man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill; it is well established law that it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art…’

There can be different standards within a profession, for example a GP will be held to the standard of a reasonably competent GP and a surgeon a reasonably competent surgeon (unless the GP is for some reason conducting surgery). However, there is no relaxation of the standard for less experienced professionals. A junior surgeon will be held to the same standard as an experienced surgeon (Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority (1987) (HoL)).

BREACH

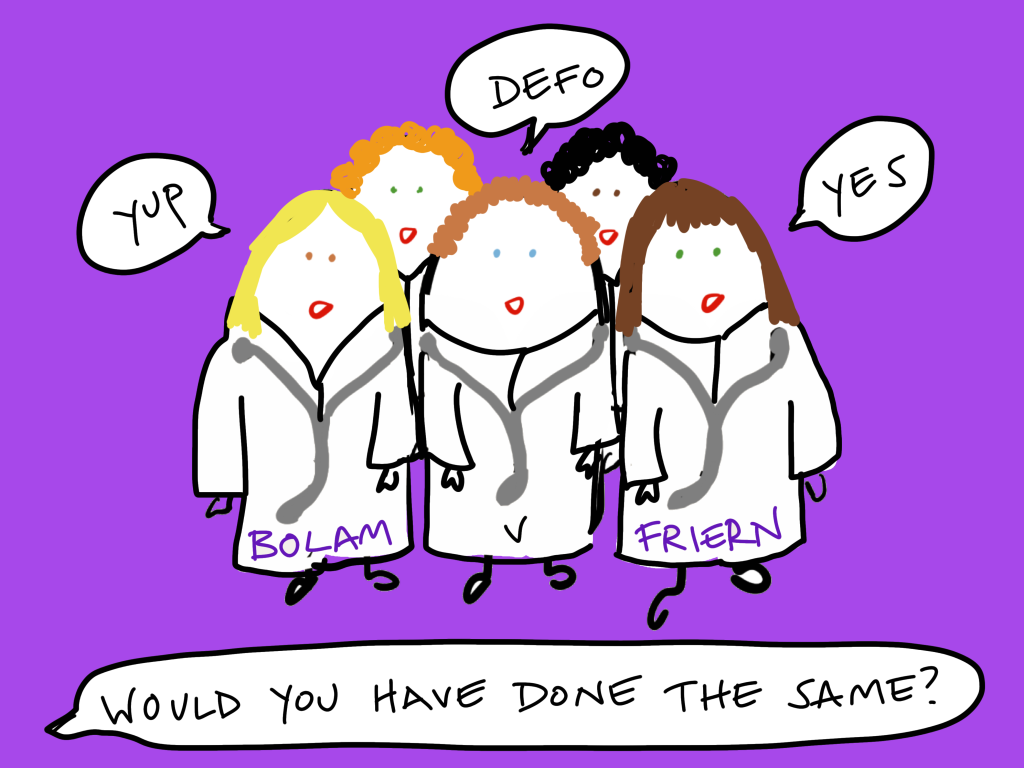

McNair J, also in Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957) (HC), set out that if a defendant could show that other professionals would have acted in the same way then they will not have breached their duty of care.

‘A doctor is not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a reasonable body of medical men skilled in that particular art’.

It does not matter that there may also be a body of professionals who hold the opposite view. Judges realise that they are not experts in other professional fields so will rarely state that one opinion is better than another, they accept that there will be differences of opinion within a profession.

Bolam had been given Electro-Convulsive Therapy. His doctors did not give him sedatives beforehand and he fell and broke his pelvis. There was no breach of duty because the medical world was divided as to whether to administer sedatives or not, so it was reasonable not to have done so.

The reasonable body does not mean the majority. In De Freitas v O’Brien and Connolly (1995) (CoA) 11 consultants out of 100 would have acted as the defendant did. This was sufficient to constitute a reasonable body of opinion.

The Bolam Test was added to by the case of Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority (1997) (HoL).

A child was brought into hospital with croup. He was under observation and suffered several episodes of breathing difficulties from which he recovered but then shortly after had a cardiac arrest and died. The doctor in charge hadn’t assessed the child because her beeper had run out of battery. The mother sued claiming that her son would have survived if the doctor had come and he had been incubated. However, the doctor argued that even if she had seen the patient she would not have incubated him and that this course of action was backed up by a reasonable body of medical opinion.

The court agreed and the doctor was not liable; however, they added to the Bolam Test stating that any reasonable body of opinion must also be logical and defensible. It was not enough to simply state that other professionals would have done the same.

Taaffe v East of England Ambulance Service NHS Trust (2012) (HC) is a rare example of when the courts have applied the Bolitho test and rejected a medical professional’s argument that they were following a reasonable body of opinion. A woman with chest pains was examined by ambulance paramedics. They did not take her into hospital because her pain had subsided by the time they arrived and she had an appointment with her GP the next day. She died of cardiac arrest five days later. Even though other paramedics would have done the same this action was seen as illogical and unreasonable; they should have taken her in for examination.

INFORMING PATIENTS ABOUT RISKS

Medical professionals have a duty to inform patients of the risks of any treatments or procedures. For many years the leading case in this area was Sidaway v Board of Governors of the Bethlam Royal Hospital (1984) (HoL) in which a woman suffered paralysis after a back operation. She had not been informed of this risk but it was not held to be a breach of duty because there was only a 1% chance of the risk happening and she had not specifically asked the doctor about the risks.

In Chester v Ashfar (2003) (HoL) the patient was not informed about the very small risk of a certain complication associated with a back operation. Unfortunately the complication materialised but not because of any negligent act committed by the doctor. Chester sued claiming a breach of duty to inform her of the risks. Chester admitted that if she had known of the risk she would have probably had the operation anyway but just at a later date after more consideration. The defendant surgeon argued that the ‘but for’ test could therefore not be satisfied because the risk would have been the same at any date so. Despite this, the House of Lords, in a 3-2 split decision, found legal causation on policy grounds, the surgeon owed a duty to inform of risk that he had breached and the claimant had suffered damage for which she should be compensated. Note that this decision is seen as problematic because of the judges’ decision to depart from the normal rules of causation.

The current leading case in this area is Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) (SC).

A patient must be informed of any material risk, reasonable alternative or variant treatments. Whether a risk is material depends on whether a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk or the doctor is, or should reasonably be, aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to it. This should be based on an on-going dialogue with the patient and not on risk percentages, there should be a culture of informed consent.

Montgomery had diabetes which often leads to larger than average babies. She was of smaller than average stature. Larger babies can be at a 9-10% risk of shoulder dystocia, when the baby’s shoulders are too large to fit through the birth canal and the baby has to be helped out which can lead to complications. Montgomery was not told about this risk or given the opportunity to elect to have a caesarean. The baby did get stuck and as a result was starved of oxygen, leading to cerebral palsy. The doctor was liable for not having alerted her to this risk and giving her the opportunity to have an elective caesarean.

The only exception is if a medical professional believes that informing the patient of a risk would be detrimental to their health.

LIMITATIONS

Defendants cannot be expected to foresee risks that are unknown at the time. Their actions will be judged against the knowledge at the time (Roe v Ministry of Health (1954) (CoA)).

Roe was paralysed by an injection of anaesthetic. It later transpired that the anaesthetic had been contaminated because of microscopic cracks in the vials it was kept in. This fact was unknown to the medical profession at the time. Although it was known by the time of the court case this could not be taken into consideration.

However, professionals are not expected to know everything or be up-to-date with every change, only what is reasonable. In Crawford v Charing Cross Hospital (1953) (CoA) the claimant was suing an anaesthetist. He claimed that the anaesthetist should have known about a specific risk because there had been an article about it in The Lancet six months before. The court rejected this argument, it would place an impractical burden on professionals to expect them to know about every development in their field.

FACTUAL CAUSATION

RES IPSA LOQUITUR

Res ipsa loquitur means ‘the situation speaks for itself’. This doctrine can be used when, although there is no available evidence of a specific act of negligence, the injury could only have been caused by negligence. This creates a rebuttable presumption and the defendant must provide evidence to the contrary if they wish to rebut it (Scott v London & St Katherine Docks (1865) (Court of Exchequer)). However, the courts will only use this doctrine sparingly, in the most extreme and obvious cases.

In Mahon v Osborne (1939) (CoA) the fact that a surgical swab was left inside a patient after an operation was an example of res ipsa loquitur. Although the claimant could not prove that this is exactly what had happened the only logical explanation was that it had been left there by one of the medical staff during the operation. Or Cassidy v Minister of Health (1951) (CoA) in which the claimant had an operation to correct two stiff fingers and woke up with four stiff fingers.

‘BUT FOR’ TEST

The ‘but for’ test (Cork v Kirby MacLean (1952) (CoA)) is used for proving factual causation in professional negligence cases. The claimant must prove, on the balance of probabilities, that ‘but for’ the breach the damage would not have happened, i.e. it is the most likely reason.

In Barnett v Kensington and Chelsea Hospital (1969) (HC) a man died from arsenic poisoning. When he arrived at hospital feeling unwell he was not examined by a medic but told to go home and see his GP. However, it was proven that even if he had been examined he would still have died. But for the defendant’s breach he would still have suffered the damage.

The case of Hotson v East Berkshire Health Authority (1987) (HoL) also illustrates this point. Hotson sustained a serious leg injury when he fell from a tree. The injury was not properly diagnosed or treated for five days because of the defendant’s negligence. Hotson subsequently developed avascular necrosis and was left with a permanent deformity of the left hip. Breach of duty was admitted but causation was challenged. The judge at first instance stated that there was a 75% probability that the deformity would have occurred despite the breach but went onto award the claimant damages on the 25% chance that it was caused by the negligence. This was overturned by the House of Lords. If the probability that the damage was caused by the negligent act was only 25% then this could not satisfy the ‘but for’ test and the defendant was not liable.

MULTIPLE CAUSES

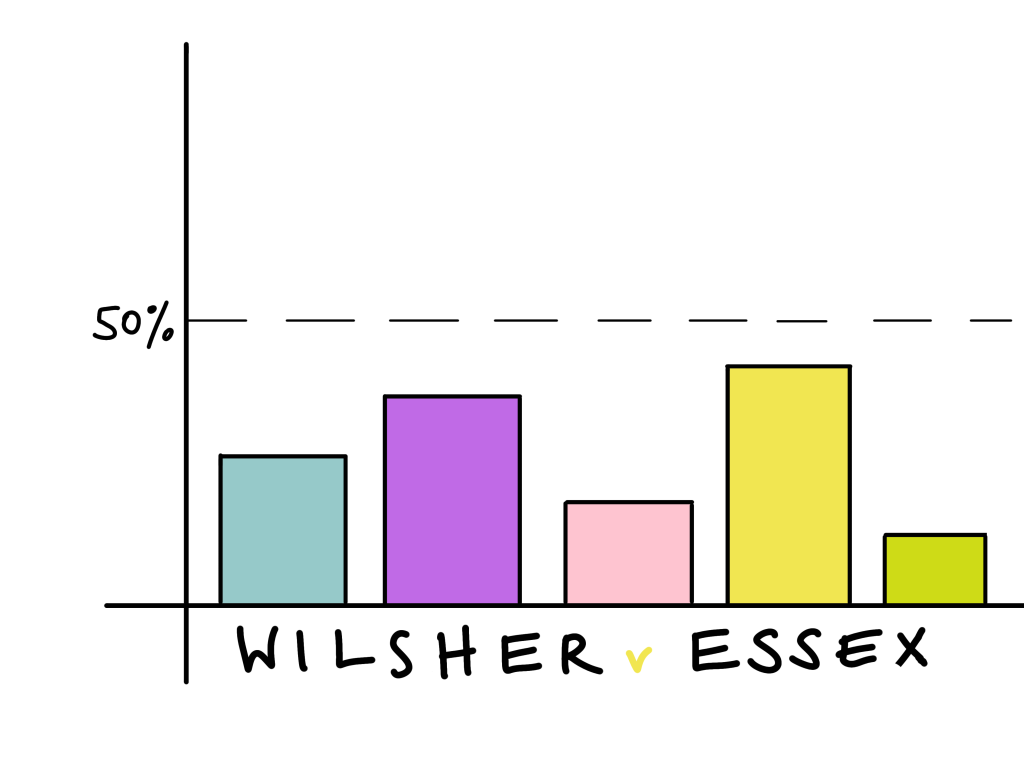

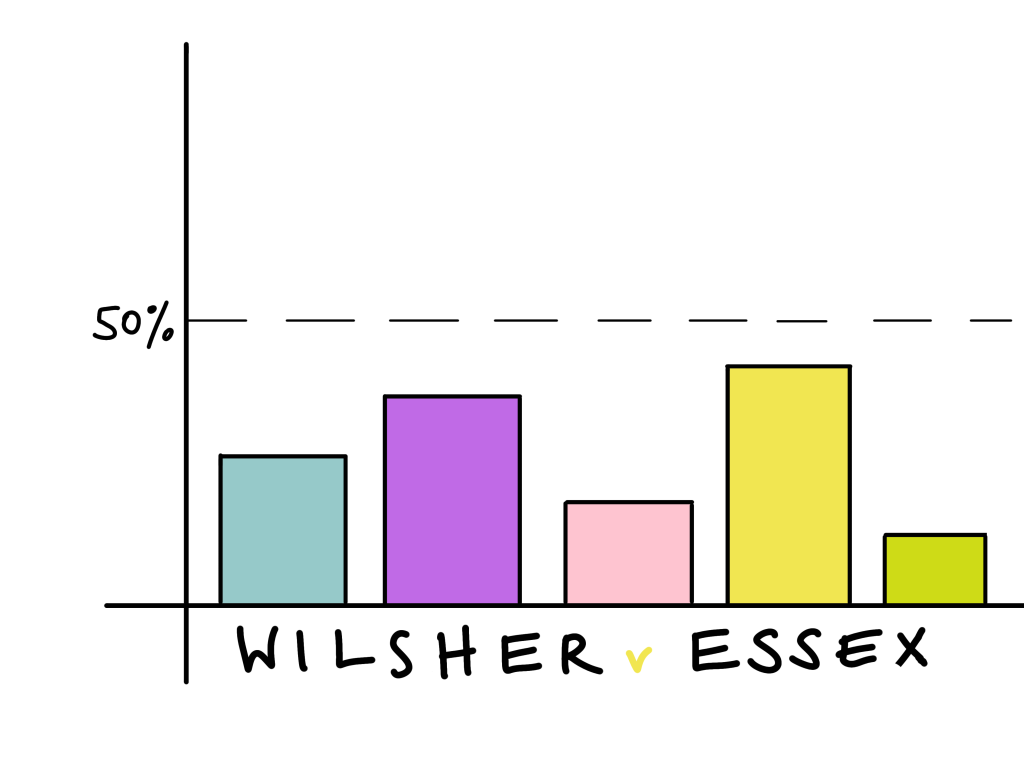

If there are multiple causes (both negligent and non-negligent) then the claimant must prove, on the balance of probabilities, using the ‘but for’ test that the negligent act caused the breach (rather than one of the non-negligent causes). In other words, that is was over 50% more likely to have been the cause (Wilsher v Essex AHA (1988) (HoL)).

There were five identifiable reasons why a premature baby had suffered damage to its sight. One was the negligent act of the doctor (twice administering too much oxygen), the others were all non-tortious reasons such as being premature. The claimant was unable to prove that, on the balance of probabilities, the negligent act was over 50% responsible and therefore the most likely cause of the damage. Therefore the hospital could not be held liable.

MATERIAL CONTRIBUTION

Very occasionally in medical negligence cases the courts will deviate from the ‘but for’ test and apply the material contribution to risk test as set out in Bonnington Castings v Wardlaw (1956) (HoL). The negligence must have contributed to the damage, not just the risk of damage, and it must have been material, i.e. more than negligible.

For example, in Bailey v Ministry of Defence (2008) (CoA) Bailey underwent an operation to remove gallstones. A negligent lack of post-operative care meant that she had to undergo further procedures. She also contracted pancreatitis (not due to any negligence). These factors led to her becoming extremely weak. She subsequently choked on her own vomit causing cardiac arrest and brain damage. The argument was that had she not been very weak she would have been able to stop herself choking. It was impossible to establish from the evidence that ‘but for’ the lack of post-operative care the damage would not have occurred. However, the judge at first instance held that the negligent act had materially increased the risk of harm and this was upheld by the Court of Appeal.

‘In a case where medical science cannot establish the probability that but for an act of negligence the injury would not have happened but can establish that the contbution of the negligent cause was more than negligible, the but for test is modified and the Claimant will succeed.’ Waller LJBailey v Ministry of Defence (2008) (CoA)

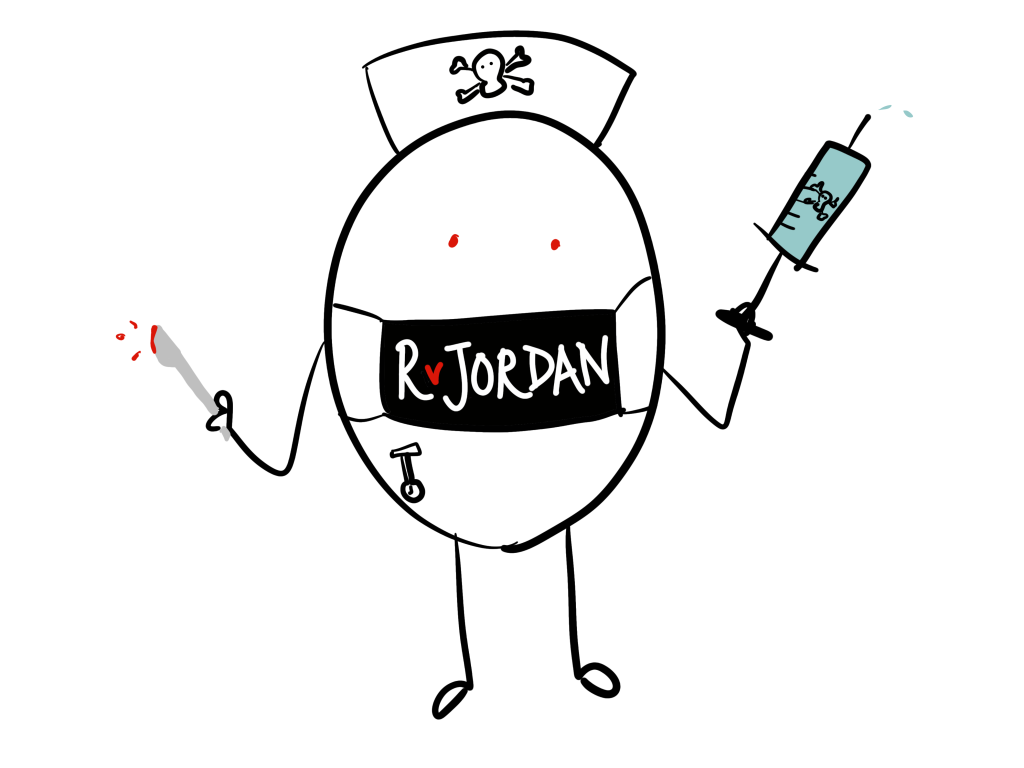

LEGAL CAUSATION

In general an intervening act of medical negligence will not break the chain of causation. The claimant would not have been in hospital if it had not been for the negligent act of another. Medical negligence will only break the chain if it is ‘palpably wrong’ (R v Jordan (1956) (CoA)).

The victim was hospitalised after being stabbed by the defendant. Whilst in hospital he was given an excessive amount of intravenous liquids and a drug to which he was known to be allergic. These acts of medial negligence led to him contracting pneumonia from which he died. They were deemed to be ‘palpably wrong’, breaking the defendant’s chain of causation.

In Webb v Barclays Bank; Webb v Portsmouth Hospitals Trust NHS Trust (2001) (CoA) Webb had fallen at work and badly injured her leg. Without being informed of any alternatives her leg was amputated. She argued that she would have chosen an alternative to amputation if she had been given the choice. However, the doctor’s negligence was not sufficient to break the chain of causation and the employer remained liable.