JUMP TO: NEGLIGENT MISSTATEMENTS | DEFECTIVE PRODUCTS | DEFECTIVE PREMISES | NEGLIGENT SERVICES | REVISE | TEST

PURE ECONOMIC LOSS

In general, compensation is not available for pure economic loss only physical damage caused by a negligent act and any consequential economic loss. A good example of this is the case of Spartan Steel & Alloys v Martin & Co (1973) (CoA).

The defendant’s negligence led to a stainless steel factory’s power supply being cut off for 15 hours. Products that were in the course of being made were ruined (physical damage) and any profit on the sale of those items was also lost (consequential economic loss). These were both recoverable. In addition the claimant claimed the lost profit from products that they could not make whilst the power was off. This was pure economic loss and could not be recovered.

Economic loss caused by damage to property that does not belong to the claimant will be classed as pure economic loss. In Weller & Co v Foot and Mouth Research Institute (1965) (HC) the claimant in this case was an auction house that had lost profits on beef sales because of a livestock travel ban. The ban had been necessary because of a leak of foot and mouth disease caused by the defendants. The auction house was unable to recover because it did not own the property (the cattle) and the loss was classed as pure economic loss.

NEGLIGENT MISSTATEMENTS

The case of Hedley Byrne v Heller (1963) (HoL) introduced the exception to the rule against recovery of pure economic loss. If pure economic loss is caused by a negligent misstatement then the claimant may be able to recover.

Hedley Byrne had been hired by a company to buy advertising space. Before contracting Hedley Byrne twice contacted the company’s bank (Heller) asking for assurance that the company was financially sound. Twice the bank stated that the company was. When the company collapsed Hedley Byrne sued Heller for loss caused by a negligent misstatement. In this instance they were unable to recover because the bank had included a disclaimer in their statement to avoid liability. However, in obiter dicta the court set out the situation in which a party could recover pure economic loss caused by a negligent misstatement.

*Note that today any disclaimer such as this would be subject to the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977.

In order for a claim of negligent misstatement to be successful the claimant must show that there was;

- A special or fiduciary relationship between the claimant and defendant,

- The defendant voluntarily assumed responsibility for the statement, and

- It was reasonable for the claimant to have relied upon the statement.

SPECIAL OR FIDUCIARY RELATIONSHIP

A special or fiduciary relationship must exist between the parties. In other words there must be a relationship of trust and confidence. This will depend upon the facts of the case.

SPECIALIST SKILL

If one party has greater skill or specialist knowledge in the subject of the statement then it will be assumed by the court that there was a special relationship of trust and confidence. It is unlikely that a special relationship will be found between two parties of equal skill. See the case of Esso v Mardon (1976) (CoA).

Before leasing a petrol station from Esso Mardon had been told by an Esso employee that the station would sell at least 200,00 gallons per year. In fact it sold only 78,000. Mardon sued Esso but his claim in negligence was for pure economic loss. The court held that because Esso was an expert in the field of petrol station output and had much greater knowledge than Mardon there was a special relationship between the parties. The employee had assumed responsibility when he made the statement and Mardon had relied upon this when deciding to lease the petrol station.

Normally this relationship will be in a business context but it is possible to find the same relationship in a social situation. In Chaudry v Prabhaker (1989) (CoA) Chaudry asked her friend Prabhaker for advice on buying a second hand car. His advice was deemed negligent when she discovered that the car had in fact been in an accident and was worthless. Based on Prabhaker’s specialist knowledge of cars and his involvement in finding her the car there was a special relationship between the two friends.

VOLUNTARY ASSUMPTION OF RESPONSIBILITY

The defendant must have voluntarily assumed responsibility for their statement. In Hedley the defendant had not because they had specifically included a disclaimer against any responsibility for the statement.

In Williams and Reid v Natural Life Health Foods (1998) (HoL) the claimants bought a franchise from the defendants. The defendants had produced a brochure that gave information about projected income which the claimants stated was negligent. However, before the case could be heard Natural Life went into liquidation so the claimants tried instead to sue the Managing Director who had created the projections. The claim failed, the courts found no voluntary assumption of responsibility on the part of Mr Mullins in relation to the claimants. He had never been involved directly with the claimants in any negotiations and there was nothing to indicate that he had assumed personal responsibility for the statements made to the claimant. Therefore, only the company could be held responsible not the individual.

REASONABLE RELIANCE UPON THE STATEMENT

The claimant must have relied upon the statement and it must have been reasonable to do so. There can be no special relationship if there was no reliance or reliance was unreasonable.

In Caparo v Dickman (1990) (HoL) Dickman had audited the accounts of a company. Caparo had relied upon those accounts when deciding whether or not to invest in the company. The audit showed that the company was prospering but after buying shares Caparo discovered that the company was basically worthless. They sued Dickman for negligent misstatement. However, the court found that the audit was a statement designed for existing shareholders and not for potential investors therefore it was unreasonable for Caparo to have relied upon it. It would have been reasonable for Caparo as a shareholder to have relied upon it but the class of potential investors (future shareholders) being infinite no special relationship could exist.

In some cases a statement prepared for one party can be reasonably relied upon by another. In Smith v Eric Bush (1990) (HoL) Mrs Smith paid more for her house than it was worth based upon a negligent property survey compiled by the defendants.. The survey had been created for her mortgage company and not specifically for her. However, the court held that it was very common for a purchaser to rely upon the mortgage survey rather than pay for another. Eric Bush would have known that she might rely upon it and it was reasonable for her to do so.

ACTUAL RELIANCE UPON THE STATEMENT

The claimant must have actually relied upon the statement. In JEB Fasteners v Marks, Bloom & Co (1983) (CoA) the court held that the claimant had not in fact relied upon the incorrect accounts compiled by the defendants when making a decision about acquiring the business. Aware of some mistakes in the accounting there was evidence to show that they had relied upon other information.

In general a statement prepared for one purpose cannot be used for another. In Reeman v Department of Transport (1997) (CoA) a certificate of seaworthiness was found to have been negligently written. It was unreasonable for the claimant to have relied upon this statement for the purpose of valuing his boat as the true purpose of the certificate was to ensure maritime safety.

DEFECTIVE PRODUCTS

It is also categorised as pure economic loss if a product is inherently defective, i.e. it was damaged when sold. Any loss will therefore not be recoverable in tort, the claimant would have to bring a claim in contract instead. For example in Donoghue v Stevenson, Mrs Donoghue would not have been able to recover in tort if she had noticed the snail before drinking the beer (thereby not sustaining any physical damage). The product was defective when it was bought and any loss would have been pure economic loss and unrecoverable in negligence.

However, at one point the courts were more willing to allow pure economic claims for defective products, the ‘high water mark’ is considered to be Junior Books v Veitchi (1983) (HoL). Junior Books had a new factory constructed and gave the builders very specific instructions as to the type of floor needed. When the floor was installed by Veitchi, a flooring specialist sub-contracted by the builders, it was found to be defective. No damage to property resulted from the defect. Junior Books sued the flooring specialists in tort for pure economic loss. This claim was allowed by the court applying the Hedley Byrne v Heller principle. Vietchi held a position of specialist skill, they had assumed responsibility for the standard of the flooring and Junior Books had relied upon this.

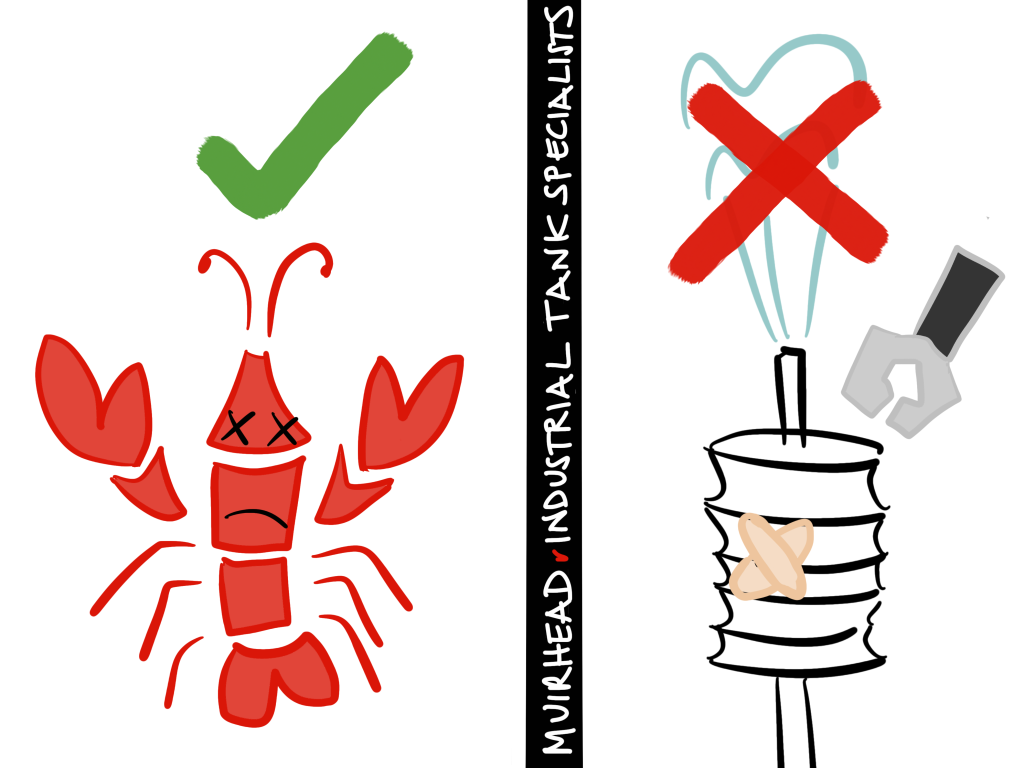

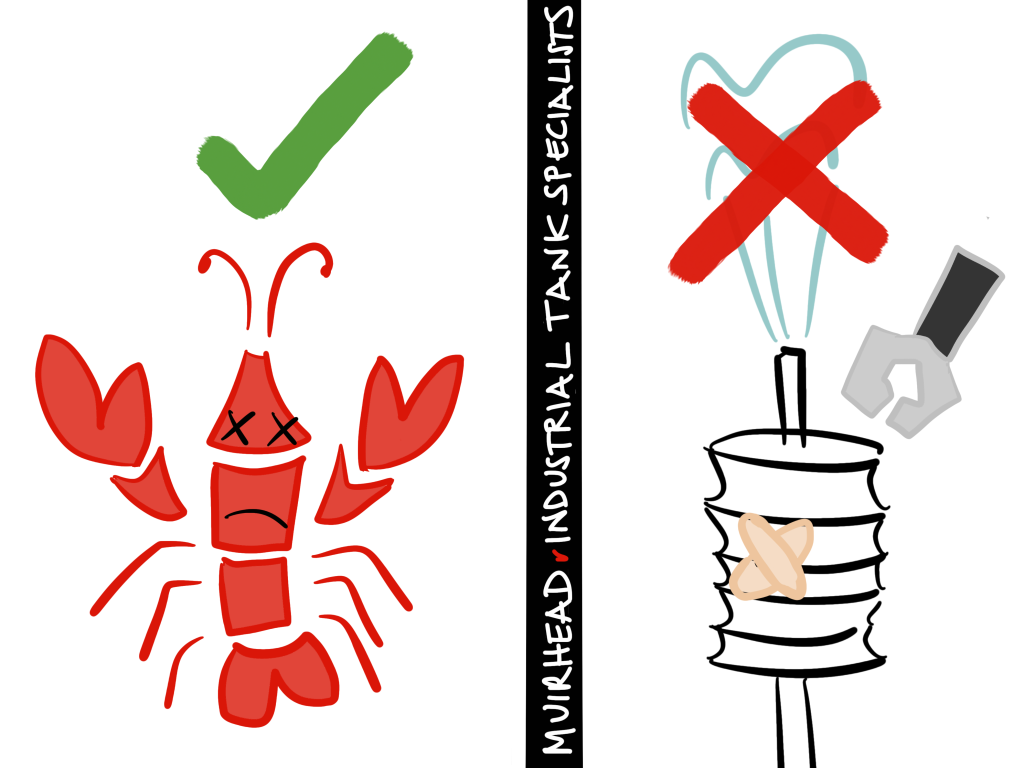

The courts have now moved away from this judgment, distinguishing it very much on its facts. A more likely way for courts to deal with a similar case today can be seen in the case of Muirhead v Industrial Tank Specialists (1986) (CoA). Faulty pumps were supplied to the claimant for use in lobster tanks. When the lobsters died the claimant sued the maker of the pumps. A claim was allowed for the price of the dead lobsters but not for the cost of the defective pumps.

DEFECTIVE PREMISES

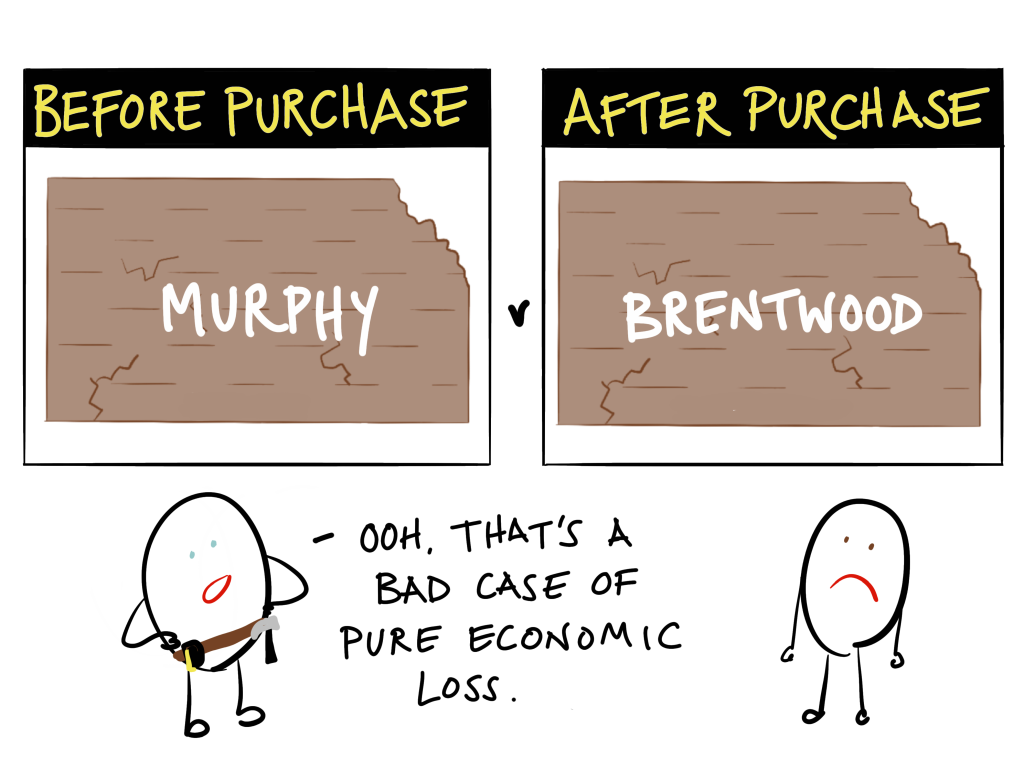

This same distinction is made for defective premises (Murphy v Brentwood District Council (1990) (HoL)).

The claimant had bought a house and subsequently discovered that there were structural defects in the foundations which knocked £35,000 off the value. Murphy was unable to claim because the defect had existed when he bought the house and no damage had yet been caused by the defect. In addition it was not a defect that put the claimant or anyone else in danger, costs would only be for repair (pure economic loss) and therefore not recoverable.

EXCEPTIONS

Obiter dicta in Murphy outlined two situations in which a claimant with a defect in their property might be able to claim for pure economic loss.

ADJOINING PROPERTIES

If the defect was posing a threat to a neighbour’s property the cost of repair may be recoverable, but this would more likely be a claim in nuisance than negligence.

COMPLEX STRUCTURE THEORY

If the defect in one part of a product has caused physical damage to another part then the costs of repairing the other part of the building may be recoverable as physical damage and consequential economic loss. However, taking this approach to property was rejected in Murphy.

NEGLIGENT SERVICES

The exception for negligent misstatements has, in some cases, expanded into what could be considered negligent services. In Spring v Guardian Assurance (1994) (HoL) an employer owed a duty to an ex-employee to write an honest reference. The defendant had written a damning reference for the claimant, they believed the contents of the reference to be true but it was found that their beliefs were based on erroneous information. Although a reference can be categorised as a statement it differs to the statements envisaged in Hedley Byrne in that it is not a statement of advice but almost a service being rendered. In addition the statement was not made for the claimant but for any prospective future employers. However, a special relationship was still found between the two parties.

The idea of a negligent service giving rise to a claim for pure economic loss also arose in White v Jones (1995) (HoL). A solicitor failed to change a father’s will before he died which should have included a £9,000 inheritance for his two daughters. The court allowed the daughters to recover this pure economic loss in negligence. This seems to be a principle confined to cases concerning wills in which the intentions of the testator and beneficiaries are the same and are not in conflict.