JUMP TO: EMPLOYEE | COURSE OF EMPLOYMENT | REVISE | TEST

VICARIOUS LIABILITY

Sometimes a third party is held liable for the actions of the defendant. This will depend upon the relationship between the defendant and the third party. Vicarious liability is most commonly found between employer and employee for torts committed whilst the defendant was in the course of employment.

WHO IS AN EMPLOYEE?

Vicarious liability will not occur in relationships that rely on a contract for services, i.e. someone employed as an independent contractor. The relationship must rely on a contract of service, i.e. someone who is an employee.

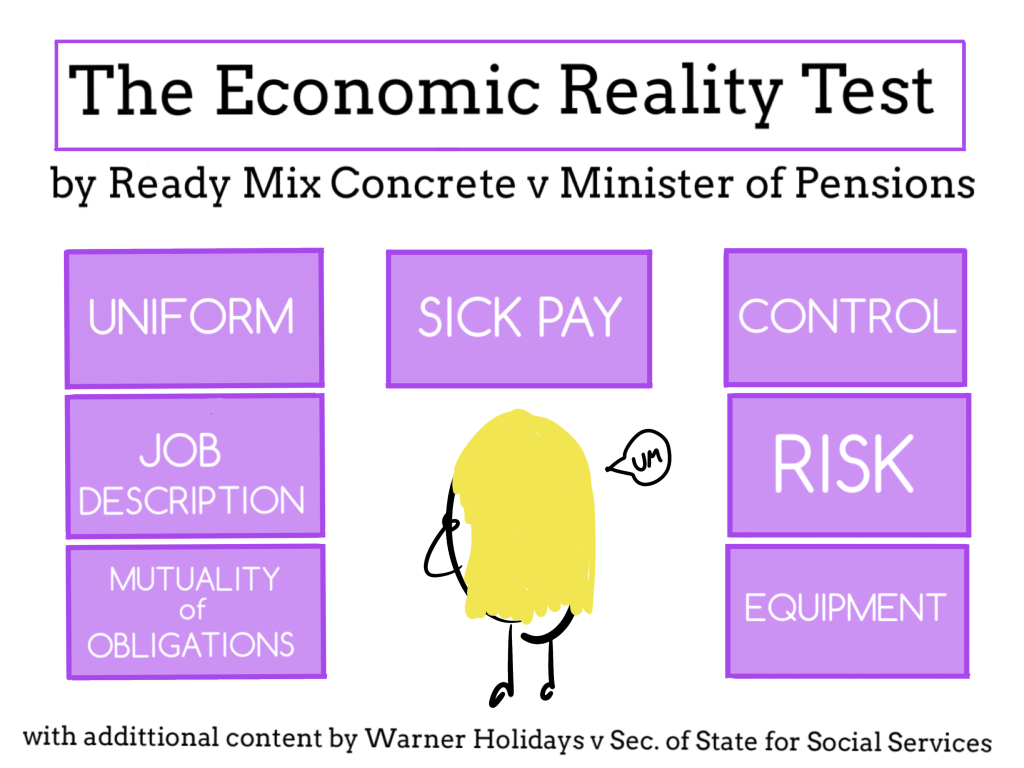

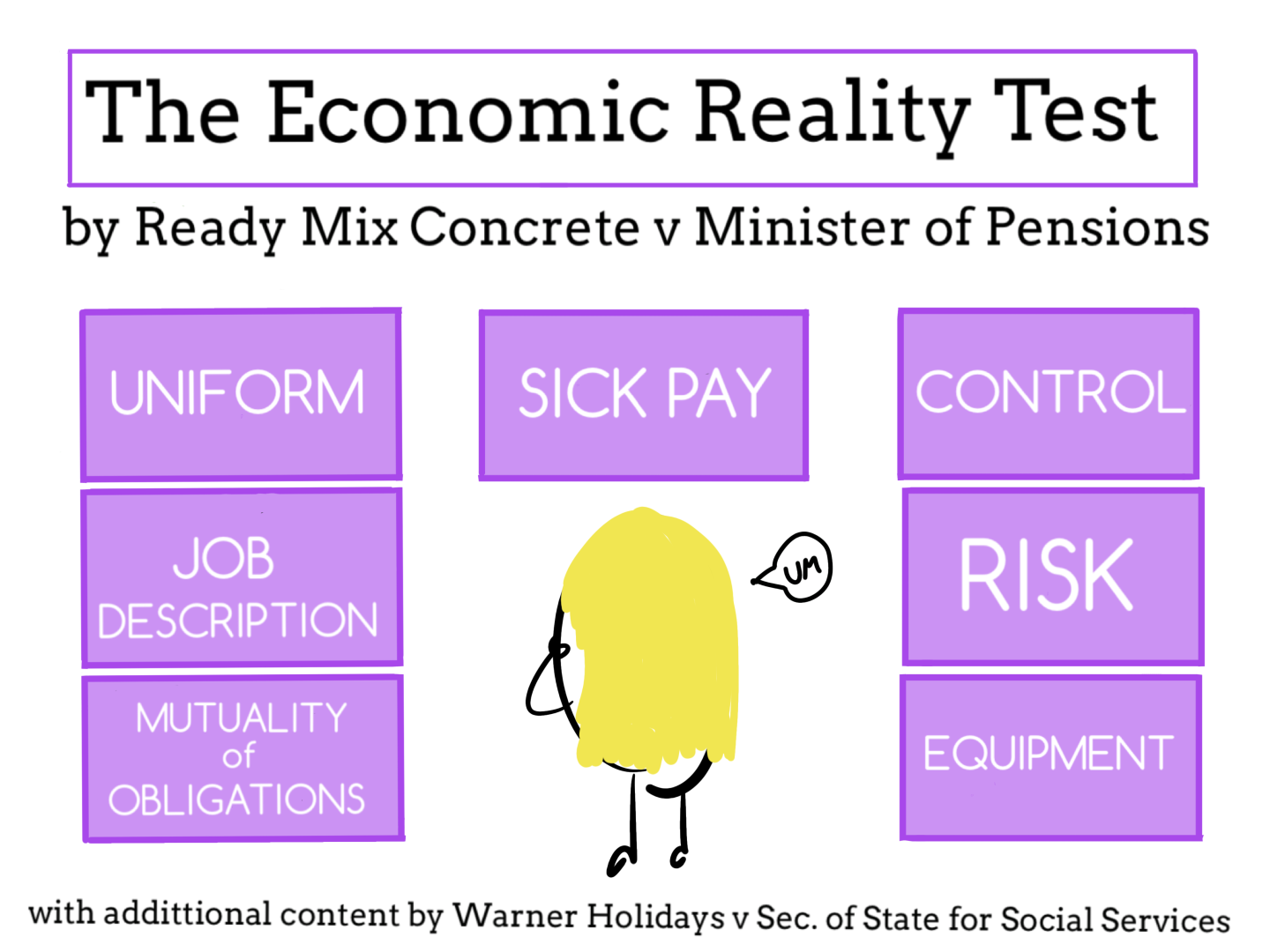

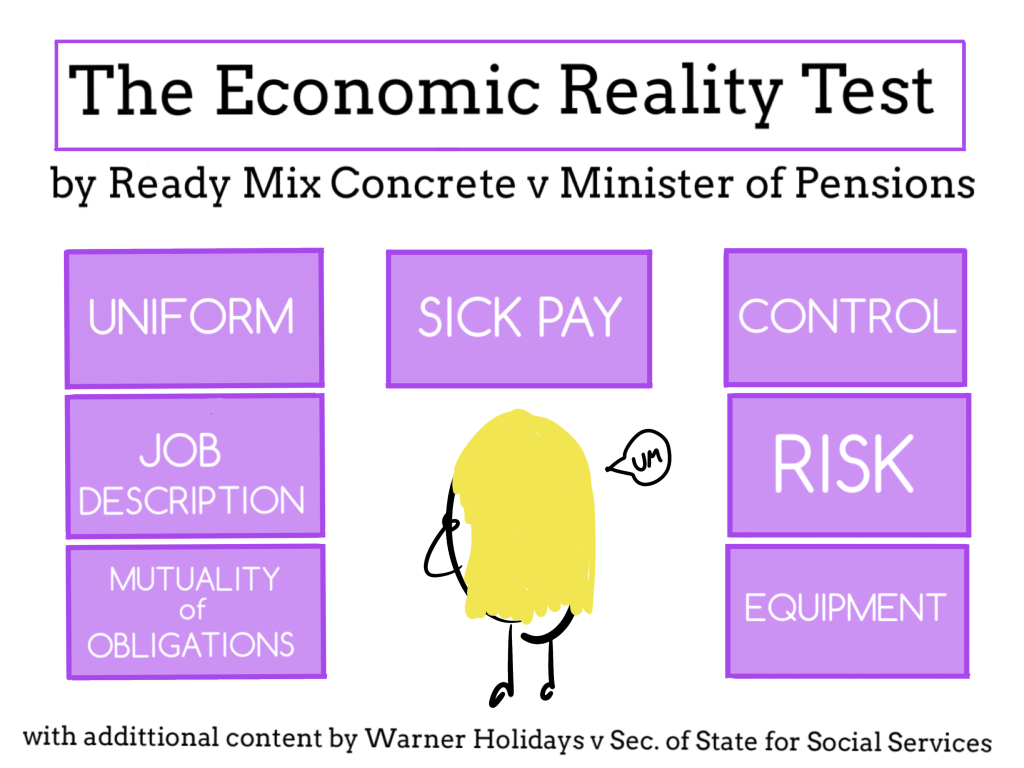

The modern approach to ascertaining whether someone is an employee or independent contractor is the Economic Reality Test, as set out in Ready Mixed Concrete v Ministers of Pensions (1968) (HC), which takes into consideration several factors to establish the overall nature of the relationship between the two parties.

In that case a lorry driver who was responsible for hiring, maintaining and insuring his lorry was an independent contractor despite the fact that the company stipulated what colour the lorry had to be and what uniform he had to wear.

The test was further developed in Warner Holidays v Secretary of State for Social Services (1983) (HC). Three musicians were found to be employees of a holiday resort as they were employed for four months for a set fee. McNeil J set out a list of factors that the court should consider; level of control, provision of tools and equipment, salary, taxes, sick pay, bearing the risk of profit and loss, residual control, control over work hours, ability to do other work, how the parties describe their relationship and mutuality of obligations. Not one of these will be conclusive but they can all be considered.

FACTORS

CONTROL

In Argent v Minister for Social Security (1968) (HC) an actor who worked part-time teaching at a school, who was allowed to teach his own content and did not have to follow the syllabus with only occasional check-ins from the Head of Department was not an employee. There was not enough control exercised over the teacher by the school.

MUTUALITY OF OBLIGATIONS

Where there is a mutual obligation between the two parties – one is expected to turn up at a certain time and the other must guarantee them work – there will generally be a relationship of employee and employer.

In O’Kelly v Trusthouse Forte (1983) (CoA) waiters (who were on a long list from which Grosvenor House Hotel chose workers on a weekly basis) were not obliged to turn up to work and the hotel was not obliged to guarantee them any work. They were independent contractors.

DESCRIPTION OF RELATIONSHIP

How the parties describe their relationship can be an indication, however it is not decisive. In Massey v Crown Life Insurance (1977) (CoA) the fact that Massey chose to call himself self-employed rather than an employee for tax purposes did not mean that he was not an employee.

PROVISION OF TOOLS AND EQUIPMENT

In Airfix Footwear v Cope (1978) (Employment Tribunal) Cope worked from home making heels for shoes. The company provided her with all of the equipment and materials and she followed instructions set down by the company. She was found to be an employee.

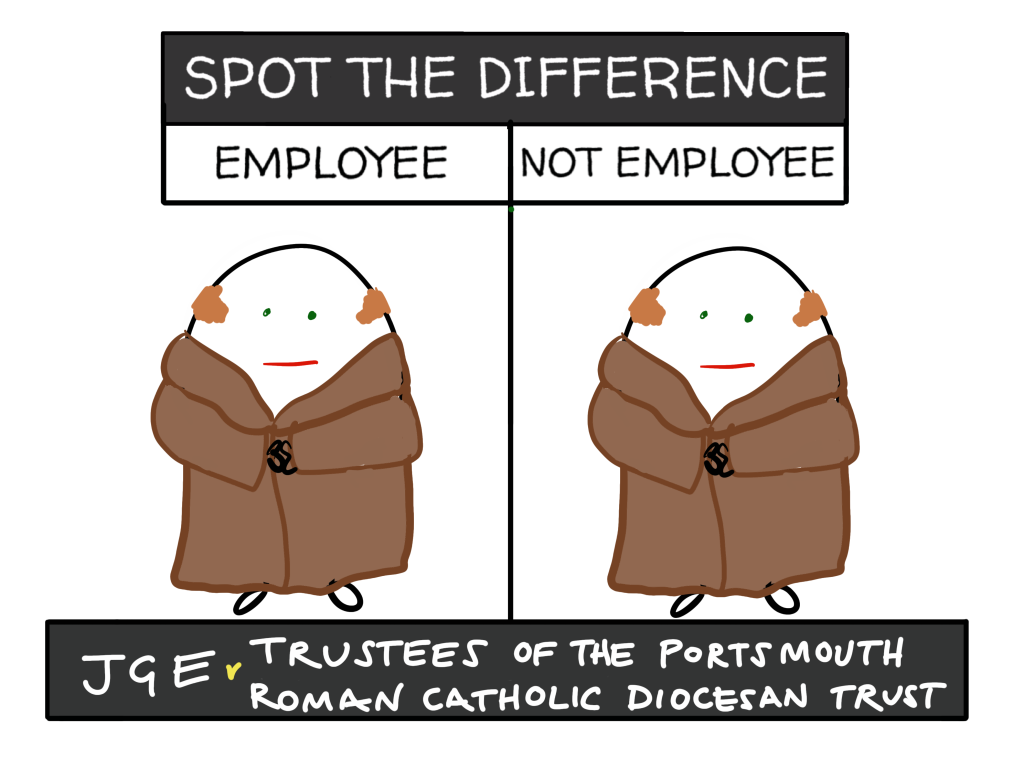

AKIN TO EMPLOYMENT

Sometimes, in order to arrive at the fairest solution, the courts will find that, although not technically an employee, the defendant’s relationship with the third party is ‘akin to employment’. In JGE v Trustees of the Portsmouth Roman Catholic Diocesan Trust (2012) (CoA) the claimant claimed that she had been abused as a young girl by a parish priest whilst she was at a children’s home run by nuns. Although not technically the Diocese’s employee the court held that their relationship with the parish priest was one of sufficient control to be ‘akin to employment’ and they were therefore liable.

Decisions like this can be justified by the fact that the aim of vicarious liability ‘is to ensure, so far as it is fair, just and reasonable, that liability for a tortious wrong is borne by a defendant with the means to compensate the victim’. Lord Philips, Various Claimants v Institute of the Brothers of Christian Schools (2012) (SC).

OUTSOURCING OF EMPLOYEES

If one employer has outsourced an employee to another party then who will be vicariously liable for the employee’s negligence? It will be whichever has more control over the employee at the time and in general, this will still be the original employer unless there is a real transfer of employment (Mersey Docks and Harbour Board v Coggins and Griffiths (1947) (HoL)).

The claimant’s trade was hiring out cranes and crane drivers. A stevedore rented a crane and driver and was in control of what work the crane driver did but did not tell him how to do it. The crane driver was trained and paid by the claimant. The court found that the original employer remained vicariously liable for the negligence of the crane driver.

It can be possible to hold both employers jointly liable but only if they have equal control over the employee (Viasystems v Thermal Transfer (2005) (CoA)). The burden of proof is on the original employer to prove that they are not vicariously liable.

DURING THE COURSE OF EMPLOYMENT

For an employer to be liable the employee must have committed the negligent act during the course of their employment. To define ‘in the course of employment’ the court will look to see if there was a ‘close connection’ between the defendant’s act and their employment. This test was set out in Lister v Hesley Hall (2001) (HoL) a case that involved the sexual abuse of students at a boarding school.

Prior to this the courts has used the Salmond Test. An act would be defined as in the course of employment if it was;

- expressly or impliedly authorised by the employer,

- incidental to something they were employed to do,

- an unauthorised way of carrying out an act that had been authorised by the employer.

This had led to, for example, victims of abuse not being able to hold their abuser’s employer vicariously liable because their actions did not fall into any of these categories. The House of Lords in Lister v Hesley Hall (2001) (HoL) overruled this test and ushered in the much less restrictive, but hard to define, test of ‘close connection’.

The difference between the two approaches can be seen by comparing the cases below, both concerning club doormen.

In Daniels v Whetstone (1962) (CoA) a dance hall doorman assaulted the claimant twice in one night. Once inside the club and once, later, outside the club. The employer was held liable for the first assault but not the second which was seen as an act of revenge outside the course of employment.

In Mattis v Pollack (2003) (CoA) a club bouncer (Cranston) threatened the claimant when he tried to break up a fight between Cranston and another customer of the club. Cranston ran home and returned to the club with a knife and proceeded to stab Mattis who was left paraplegic. The employer, Pollack, was found vicariously liable for the bouncer’s actions, even though there was an element of personal revenge involved, because there was a ‘close connection’ between Cranston’s employment and the subsequent stabbing. The court also took into consideration that Pollack had specifically told Cranston to behave aggressively, thereby helping to create the risk of him harming a guest.

The ‘close connection’ test was confirmed in Mohamud v WM Morrison Supermarkets (2016) (SC). Mohamud had asked if a Morrison’s petrol station employee could print off some documents for him. The employee had refused using racist and threatening language. When Mohamud returned to his car the employee followed him and physically assaulted him. The Court of Appeal found an insufficiently close connection between the action and the employment but this was overturned by the Supreme Court who held Morrisons to be liable because this was not a personal altercation but one that had happened in the sphere of the employee’s job of supervising the petrol station. Even though the act of the employee was totally unpredictable and unsanctioned unlike in Mattis v Pollack (2003) (CoA) where the employer encouraged the employee to act aggressively.

Below are some examples of when the courts have and have not found liability. Bear in mind that many of these cases were decided using the older, Salmond Test.

VICARIOUSLY LIABLE

In Limpus v London General Omnibus (1862) (Court of Exchequer) the driver of a horse-drawn bus tried to obstruct another bus. This was seen as an unauthorised way of fulfilling his work.

In Bayley v Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (1873) a train conductor who had been told to make sure everyone was on the correct train injured a passenger when dragging him from the incorrect train. He was performing his duties but in an unusual way.

In Century Insurance v NI Road Transport (1942) (HoL) a lorry driver caused an explosion at a petrol station by smoking whilst filling his tank. Getting petrol was seen as incidental to his work as a lorry driver, therefore the employer was liable.

NOT VICARIOUSLY LIABLE

In general, the employee must have been acting outside the scope of his employment, or on a ‘frolic of his own’ (Joel v Morrison (1834) (Exchequer of Pleas)). The driver of a horse and cart was on a detour to visit a friend when he injured the claimant. His employer was not held liable as the employee had been on a frolic of his own.

In Beard v London General Omnibus Co (1900) a bus conductor who tried to drive the bus was not acting in the course of his employment.

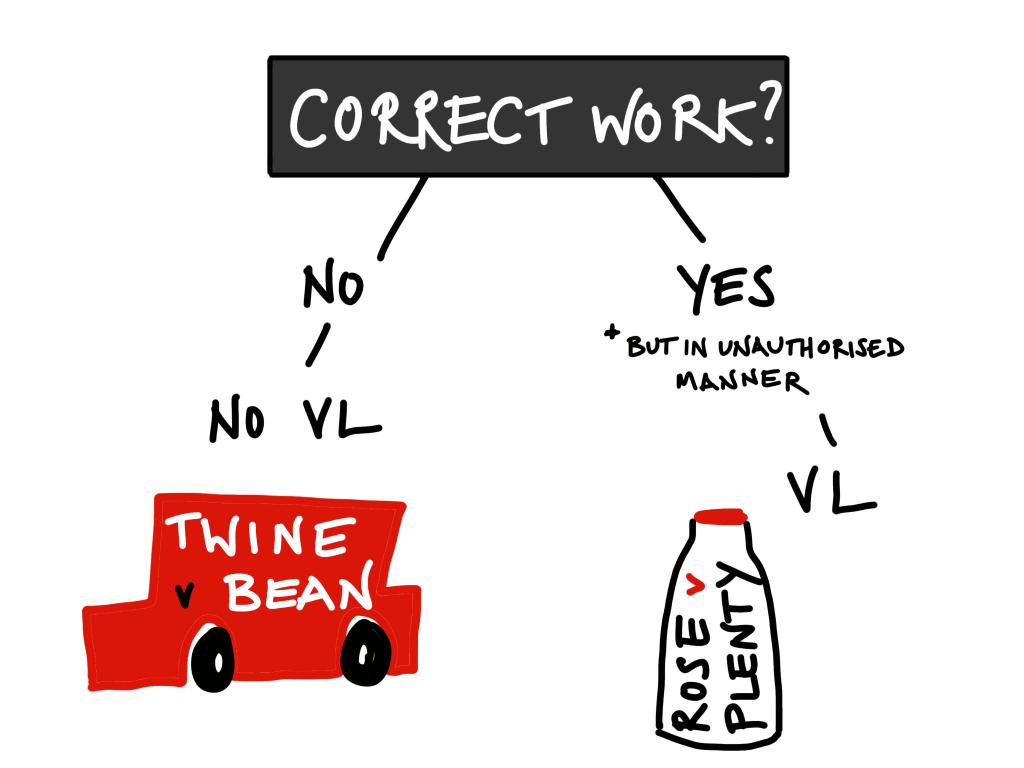

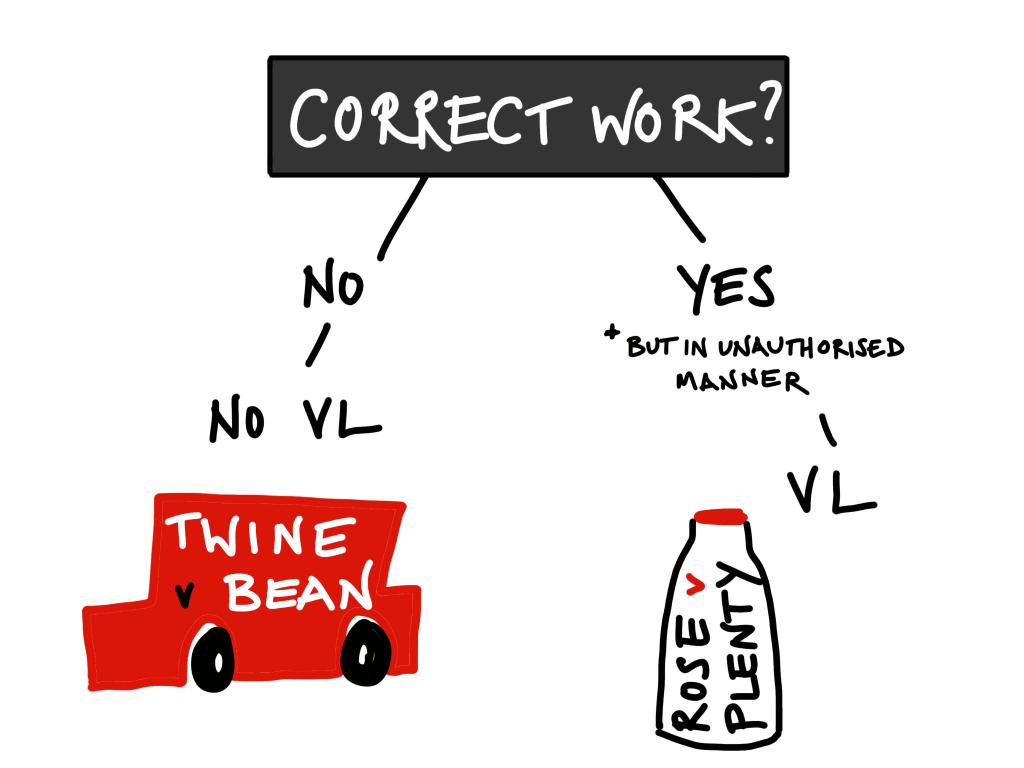

ACTION WAS FORBIDDEN

The courts are unwilling to give employers a wide mandate for avoiding liability. Therefore if the employee carries out the correct work but in the wrong way the employer will still be liable. Only if the employee goes beyond the scope of their job in a way expressly prohibited by the employer will there be no vicarious liability.

| In Twine v Bean Express (1946) (CoA) a driver picked up a passenger, something that he was forbidden to do, and injured them by driving negligently. The employer was not liable because he had done something forbidden by the employer. |

In Rose v Plenty (1976) (CoA) a milkman allowed a young boy, who was injured by the milk cart, to help him on his rounds even though this was prohibited. The court found that this was the milkman performing his work but in an unauthorised way, therefore the employer was liable. |

COMMUTING

In general, time spent travelling to and from work is not in the course of employment. The exception would be if the travel was part of the job rather than just commuting (Smith v Stages (1989) (HoL)). The defendant’s employee had been sent to do some work in another part of the country and paid for travel expenses. On his way home he caused an accident injuring the claimant. His employer was found vicariously liable because he was not commuting but travelling for work at the request of the employer. The court stated that an employer will be liable if the employee was at the time of travel going about the employer’s business. This includes travelling on the employer’s time or travelling between offices. Receipts for travel are an indication that the voyage was made in the course of employment and not commuting.