JUMP TO: TERMINATE – The Santa Clara – AFFIRM – Stocznia Gdanska SA v Latvian Shipping – ANTICIPATORY BREACH – Hochster v De la Tour | Omnium D’Enterprises v Sutherland | Frost v Knight | Johnstone v Milling | Gulf Agri Trade FZCO v Aston Agro Industrial | Universal Cargo Carriers Corporation v Citati (No. 2)

REVISE | TEST

BREACH

‘A breach of contract is committed when a party without lawful excuse fails or refuses to perform what is due from him under the contract, or performs defectively or incapacitates himself from performing’, Treitel

A breach of contract does not automatically bring a contract to an end. The remedy available will depend upon the type of term that has been infringed. Contractual terms are categorised as conditions, warranties or innominate terms (see the page on Conditions or Warranties for more information).

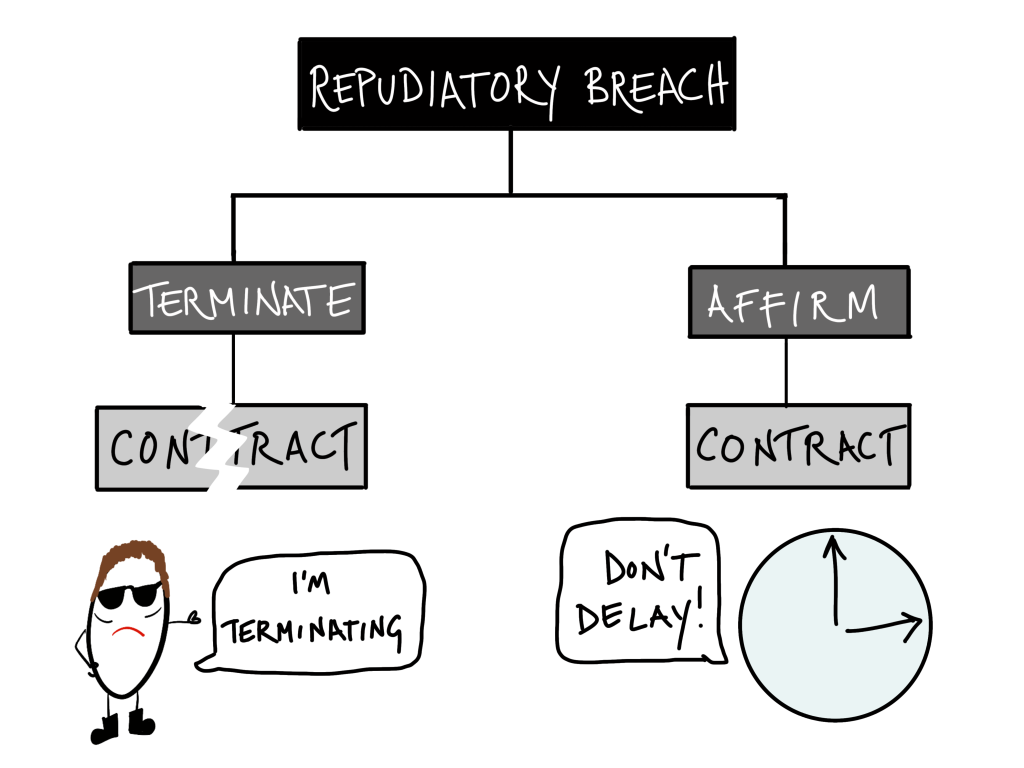

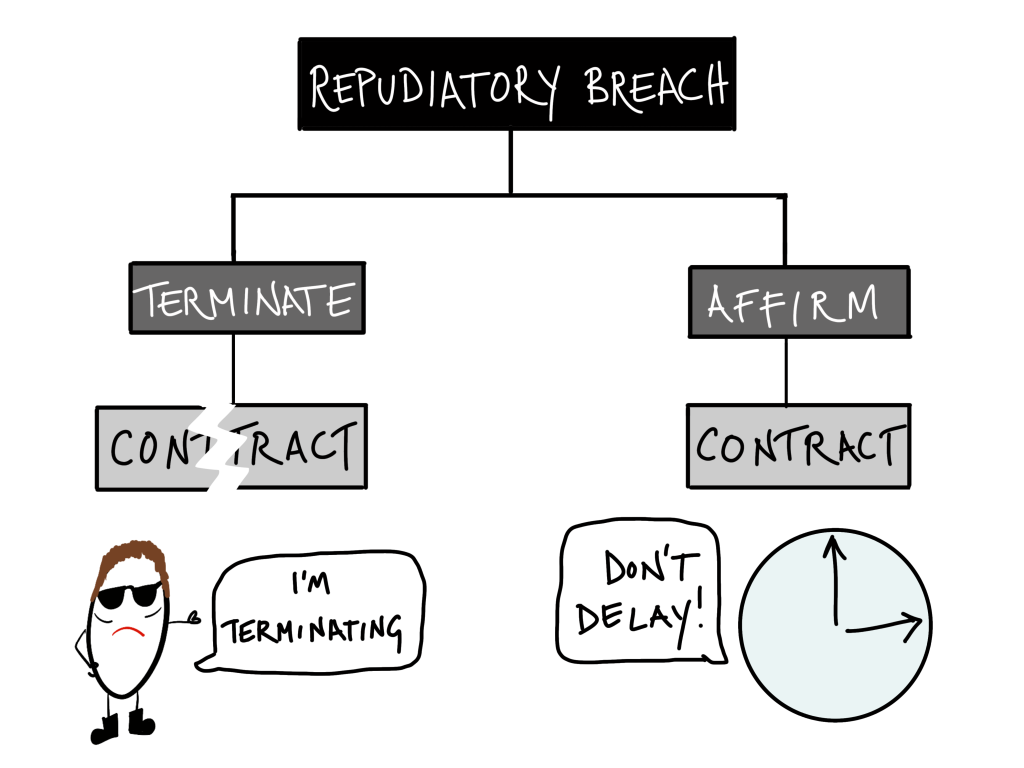

Only the breach of a condition, or innominate term with serious consequences, will give rise to a repudiatory breach and the right of election. This is the right of the innocent party to decide whether to terminate or affirm the contract. In both cases the party still has the right to sue for damages.

TERMINATE

If the innocent party chooses to terminate the contract all future contractual obligations are discharged. However, they must communicate their decision to terminate to the other party. It doesn’t matter how this is done so long as the message is objectively clear and unequivocal (Vitol SA v Norelf Ltd (The Santa Clara) (1996) (HoL)).

|

AFFIRM

If the innocent party chooses to affirm then the contract continues and both parties must fulfil their future contractual obligations. The party does not have to terminate immediately but waiting too long to communicate their decision can be taken as an implied affirmation (Stocznia Gdanska SA v Latvian Shipping Co (2001) (HC)). If the party affirms the contract they cannot decide later on to terminate it, unless the breach is ongoing or happens again.

|

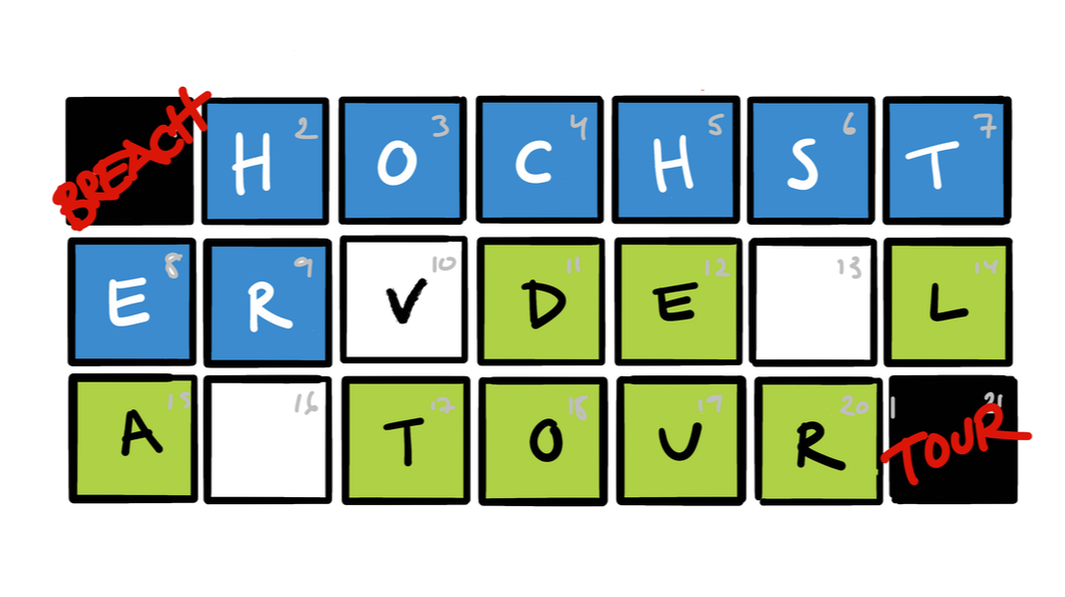

ANTICIPATORY BREACH

Breach can happen after the contract has been agreed but before actual performance of the contract has begun. This is known as anticipatory breach and usually occurs when one party informs the other that they will not be able to fulfil their part of the obligation.

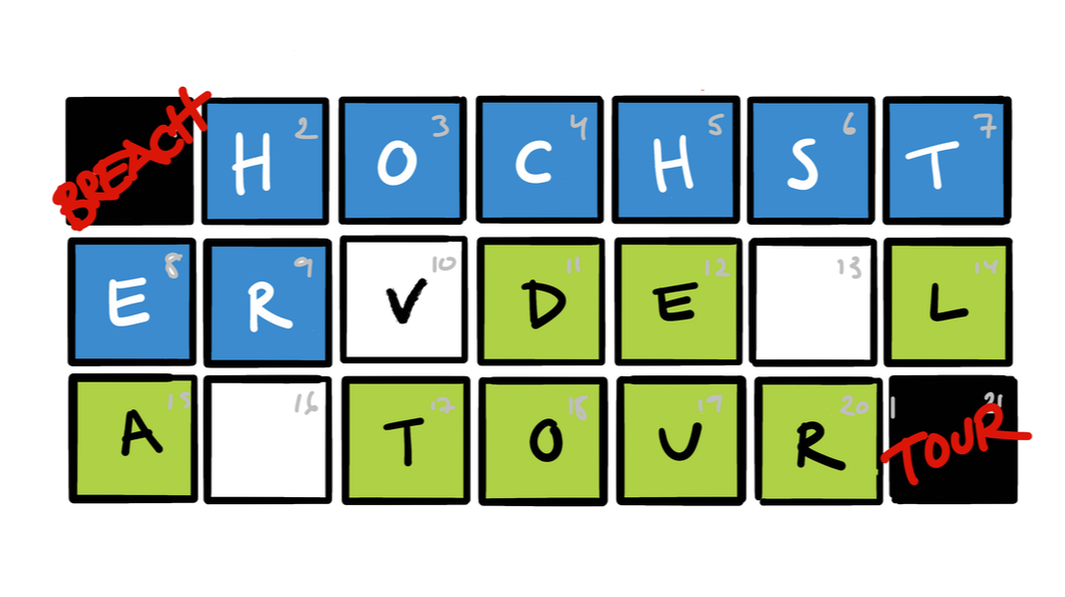

Where this occurs, the innocent party can start proceedings for breach of contract at any time from the declaration of anticipatory breach, they are not obliged to wait for the actual breach to occur (Hochster v De la Tour (1853) (HC)).

De la Tour engaged Hochster in April to act as his courier on a European trip which was due to start on 1st June. However, on May 11th De la Tour wrote to Hochster to terminate the contract. Hochster started proceedings for breach of contract on 22nd May but De la Tour argued that no action could be taken until 1st June when performance was due to take place. The court held that Hochster was entitled to bring an action against De la Tour as soon as the anticipatory breach occurred i.e. on 11th May when he wrote terminating the agreement.

An anticipatory breach can be implied, rather than expressly stated, if the actions of one party make subsequent performance of their contractual undertaking impossible. See Omnium D’Enterprises v Sutherland (1919) (CoA) in which the sale of the ship that the claimants were going to hire from the defendants equalled an implied anticipatory breach. Also see Frost v Knight (1872) (Court of Exchequer).

METHODS OF ANTICIPATORY BREACH

Some of the ways in which an innocent party may anticipate a breach is ‘where the other party by words or conduct, evinces an intention not to perform, or expressly declares that he is or will be unable to perform his obligations under the contract in some essential respect’. (Chitty on Contracts, 14th edn 2015).

Such conduct can include previous behaviour by the promisor which would allow the promisee, on a balance of probabilities, to draw an inference that the promisor is likely to commit a breach when the time arrives to perform an obligation under the contract (Johnstone v Milling (1886) (CoA)).

However, there is always the risk of early termination that the party alleging anticipatory breach must be careful of. In Gulf Agri Trade FZCO v Aston Agro Industrial AG (2008), the seller was contracted to ship 6,000 metric tonnes of Russian Feed Barley during the period 10 August to 10 October 2004. When the seller had not yet made shipment by the end of September the buyer assumed it would not be possible for the seller to deliver the barley in time and sent a notice of termination to the seller. The GAFTA Appeal Board (Grain and Feed Trade Association) held that the notice of termination was premature and thus unjustified as the buyer, ‘could not reasonably have concluded’ that the seller was in ‘anticipatory breach of the contract through impossibility or renunciation’.

In a similar case for the shipment of naphtha for loading in Karachi port the Commercial Court allowed for termination but highlighted the confusion as to whether a claimant must subjectively believe that the defendant’s words or conduct evinced an intention not to perform the contract, or whether the test is objective in that defendant’s conduct ‘would be reasonably calculated to have upon a reasonable person’ the impression of renunciation (Universal Cargo Carriers Corporation v Citati (No. 2) (1957) (CoA)).

Generally, this is a tricky area under English common law. Scholars have criticised the doctrine of anticipatory breach and have argued that other jurisdictions have better alternatives, such as the ‘doctrine of adequate assurance’ under the American Uniform Commercial Code (Reza Beheshti, 2018).