JUMP TO: PERFORMANCE – Cutter v Powell |Sumpter v Hedges | Hoenig v Isaacs | Bolton v Mahadeva | Ritchie v Atkinson | Planche v Colburn | Startup v Macdonald – AGREEMENT

DISCHARGE BY PERFORMANCE OR ACCEPTANCE

Once a contract has been discharged it releases the parties from any further obligation. A contract can be discharged (terminated/brought to an end) in the following ways;

*A contract can also be discharged via Frustration but this is dealt with on the next page.

What is required by way of performance of a contract will be determined by reference to the express terms of the contract and any implied terms. When parties enter into a contract they generally expect that its terms will be complied with. Discharge by performance requires that all of the terms of the contract have been fully complied with. The vast majority of contracts are discharged through performance without legal issue. In many cases, performance occurs simultaneously with offer and acceptance, and the contract is therefore discharged immediately. E.g. You purchase goods at the checkout till and pay for them.

ENTIRE OBLIGATION RULE

In order for a contract to be discharged by performance the entire contractual obligation must have been carried out. This is also known as the doctrine of condition precedent because full completion of one party’s promise must be completed before performance of the other party’s promise. This rule is illustrated well by the case of Cutter v Powell (1796) (Court of King’s Bench).

Cutter was employed by Powell to work on a ship sailing from Jamaica to Liverpool for which he would be paid a lump sum upon arrival. Cutter died before reaching home but his wife was unable to claim his wages for the part of the contract he had fulfilled before he died. This was because it was expressly stated in the contract that payment was conditional upon completion of the voyage. Therefore, Mrs Cutter was not entitled to claim any of her husband’s wages because the contract had been only partially performed.

AVOIDING THE RULE

Because this rule can lead to harsh results there are ways in which it can be avoided by the courts.

PARTIAL PERFORMANCE

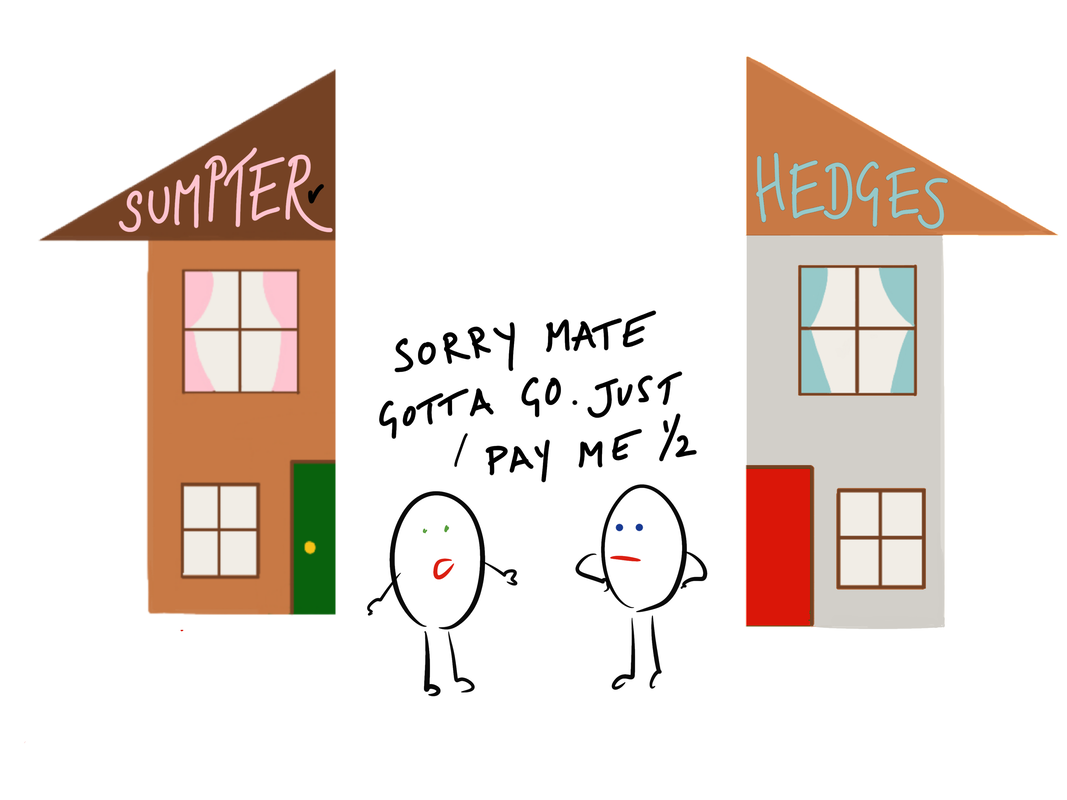

If the full contractual obligations cannot be performed then the promisee can accept partial performance but this must be voluntarily. In this case a sum is payable for the work completed on the basis of quantum meruit (‘the amount he deserves’) (Sumpter v Hedges (1898) (CoA)).

Sumpter was contracted by Hedges to build, for a lump sum, two houses and stables but abandoned the work before completion because he ran out of money. Hedges finished the work himself with materials that Sumpter had left on site. Sumpter sued Hedges for payment for the work he had completed. The court held that Sumpter was not entitled to any payment as Hedges had not voluntarily accepted the partial performance and there had been no separate agreement to pay quantum merit. Hedges had been left with no choice as to whether to adopt the work done or not because the unfinished buildings were on his land and had to be finished. However, Sumpter was able to reclaim the cost of the materials that Hedges had used as they could have been returned and Hedges had made a choice to keep them.

Quantum meruit is a type of remedy which compensates the claimant for a contractual benefit that they have given but for which they have received nothing in return. It is used by the courts to provide the claimant with reasonable remuneration based on the objective market value of the product or service. Quantum meruit can be used by the courts when there is no contract or when the contract provisions for remuneration cannot be applied.

CHECK OUT OUR SHOP FOR LAW FLASHCARDS | MIND MAPS | MUGS

SUBSTANTIAL PERFORMANCE

If substantial performance of the contract has been carried out but there are minor variations to the agreed terms then payment for the entire contract will generally be due. If the court decides that the variations or defects are sufficiently minor then payment will be due minus a proportionate deduction (Hoenig v Isaacs (1952) (CoA)).

Isaacs hired Hoenig to decorate and furnish his house. Payment was to be made in two instalments with the final one payable upon completion of the work. However, when the work was done Isaacs was dissatisfied with the work and refused to pay the final instalment. Hoenig sued Isaacs for the payment and the court held that as the contract had been substantially performed and the cost of remedying the defects was only £56 Isaacs was not able to withhold payment and he must pay Hoenig the final instalment minus the remedial cost.

The defendant, by taking the benefit of the work done under the contract, could not treat entire performance as a condition precedent, but only as a term giving rise to damages.

WHAT AMOUNTS TO SUBSTANTIAL PERFORMANCE?

The judges in Hoenig v Isaacs interpreted the term ‘substantial’ in its ordinary (literal) meaning and suggested that for performance to be substantial it does not necessarily have to be complete or to the exact satisfaction of the promisee. This was also discussed in Bolton v Mahadeva (1952) (CoA). Bolton was hired to instal a central heating system. Full installation was completed but the system was defective and Bolton refused to fix it. Even though the system had been fully installed the court held that the defects were serious enough to amount to non-substantial performance of the contract and Mahadeva did not have to pay for the work.

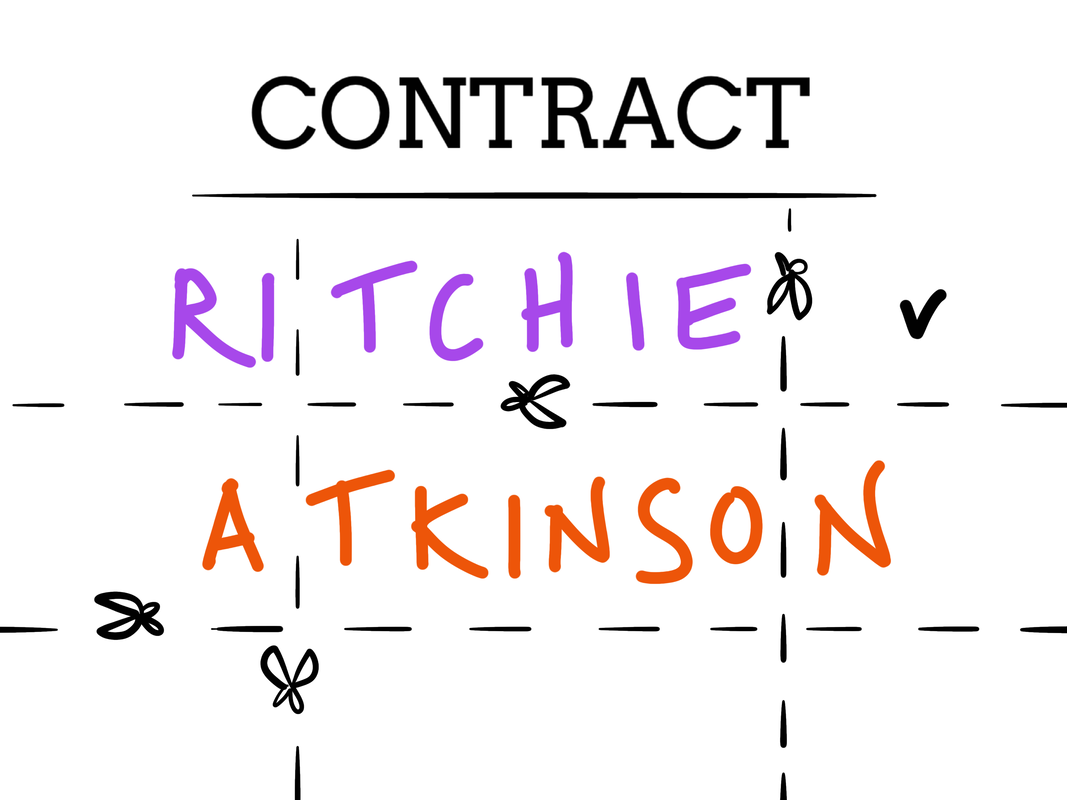

DIVISIBLE OBLIGATIONS

Some contracts are obviously intended to be divisible into parts and a breach related to one part will not equal breach of the entire contract (Ritchie v Atkinson (1808) (Court of King’s Bench)).

Ritchie agreed to carry a cargo of a specified quantity of hemp and iron. The price agreed was £5 per ton for the hemp and 5 shillings per ton of iron. However, Ritchie only carried part of the agreed quantity. This was because after loading only some of the cargo the master of the vessel decided to leave port because of a general rumour of a hostile embargo being laid on British ships by the Russian Government. Atkinson argued the contract had not been fully performed and therefore no payment was due. The court held that the contract could be divided into separate parts as the parties had agreed a price per ton. Furthermore, the rumour turned out to be true and the claimant had been acting in good faith. The claimant was thus entitled to payment for the amount carried although the defendant was entitled to damages for non performance in relation to the amount not carried.

COMPLETION PREVENTED BY THE PROMISEE

Where full and complete performance of the contract is prevented through the other party’s actions, the party unable to complete performance may claim for partial or substantial performance (Planche v Colburn (1831) (HC)).

Planche, an author, entered into a book contract with Colburn. They agreed a price of £100 payable upon completion of the book. Planche had half completed the book when the defendant (the promisee) told him to discontinue and terminated the contract. Given that half of the book had been written and that the contract was prematurely terminated by the defendant, the courts held that the claimant was entitled to recover £50 for the half completed book.

|

TENDER OF PERFORMANCE

This is whereby a party is willing to perform and attempts to tender performance of their obligation but the other party rejects the tender. The party is discharged from the contract and may claim damages for non-acceptance. An example of this can be seen in (Startup v Macdonald (1843) (Court of Common Pleas)).

Ten tonnes of oil was to be delivered by Startup to MacDonald ‘within the last 14 days of March’. Startup attempted to deliver on the evening of 31st March. However, MacDonald refused to accept it given the lateness of the hour. It was held that Startup had tendered performance within the agreed contractual period and was therefore, entitled to damages for non acceptance.

|

AGREEMENT

A contract can also be discharged (terminated) by agreement of the parties.

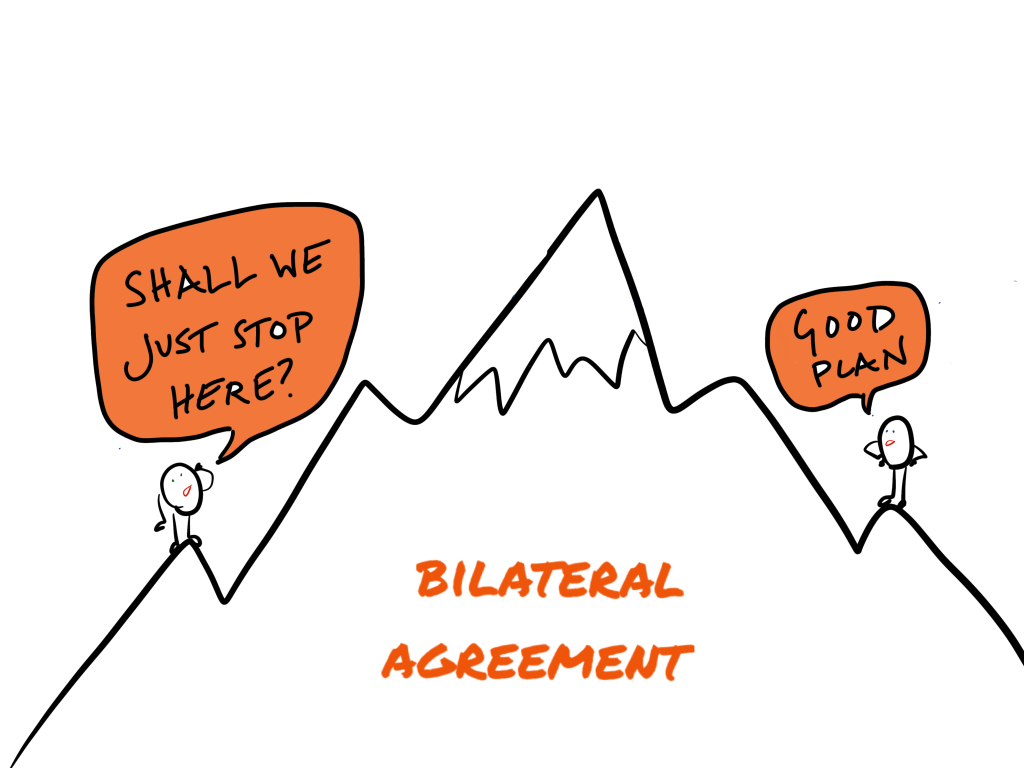

BILATERAL AGREEMENT

This is whereby the parties agree to discharge each other from performance obligations under the terms of the agreement. Provided that the parties have mutually agreed to discharge performance obligations the contract will be deemed discharged even though the parties may not have fully or partially performed all their obligations.

Whilst parties can discharge performance without any formalities, to ensure compliance it is best practice to have a legally binding (written) agreement. However, a new agreement or second contract to discharge the first requires consideration. If both parties have unperformed contractual obligations the giving up of the right to receive the other’s performance is sufficient consideration for ending the contract. Alternatively the parties may choose to vary, waive or substitute the performance obligations set under the original agreement as opposed to discharging the agreement altogether.

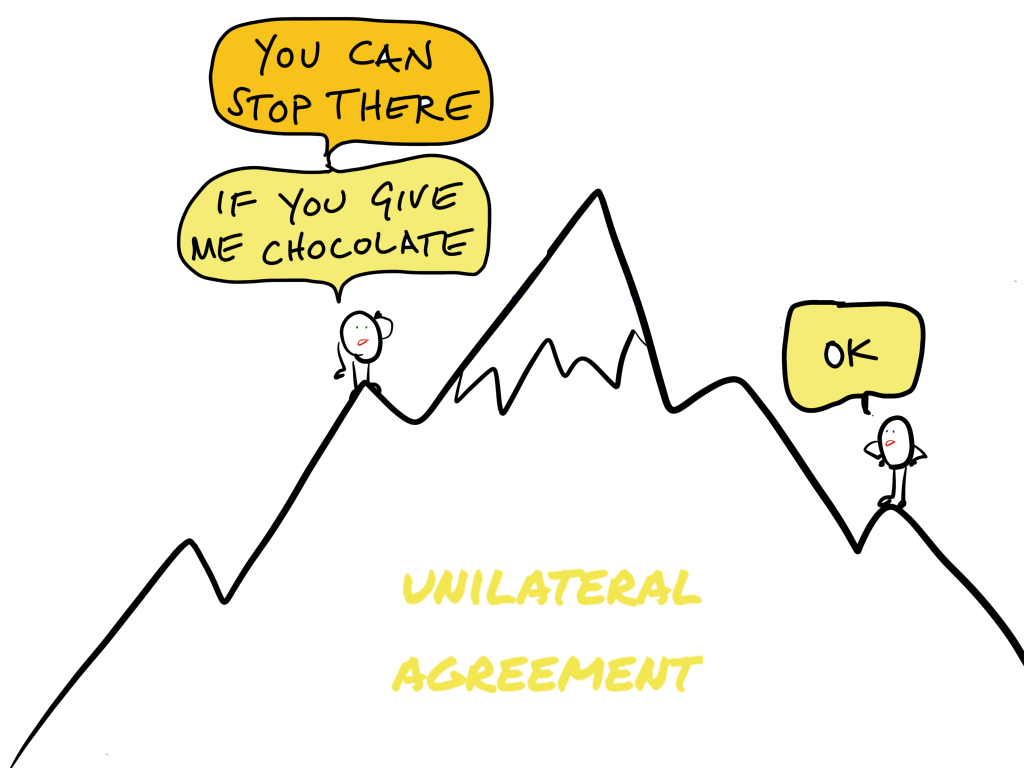

UNILATERAL AGREEMENT

This is whereby one party has completed its performance obligations and agrees to release the other party from its outstanding obligations under the contract. However, this type of agreement is only binding if supported by consideration.

An agreement to abandon the contract, unless supported by fresh consideration, will be unenforceable unless (i) the agreement is in the form of a deed, (ii) the party who has fully performed his obligations under the contract is estopped from going back upon his representation that he will not enforce the original contract or (iii) he is held to have waived his rights under that contract.