JUMP TO: PRIVITY: Dunlop Pneumatic Tyres Co Ltd v Selfridge | Tweddle v Atkinson

EXCEPTIONS: STATUTE: Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999

GROUPS: Jackson v Horizon Holidays | Woodar v Wimpey

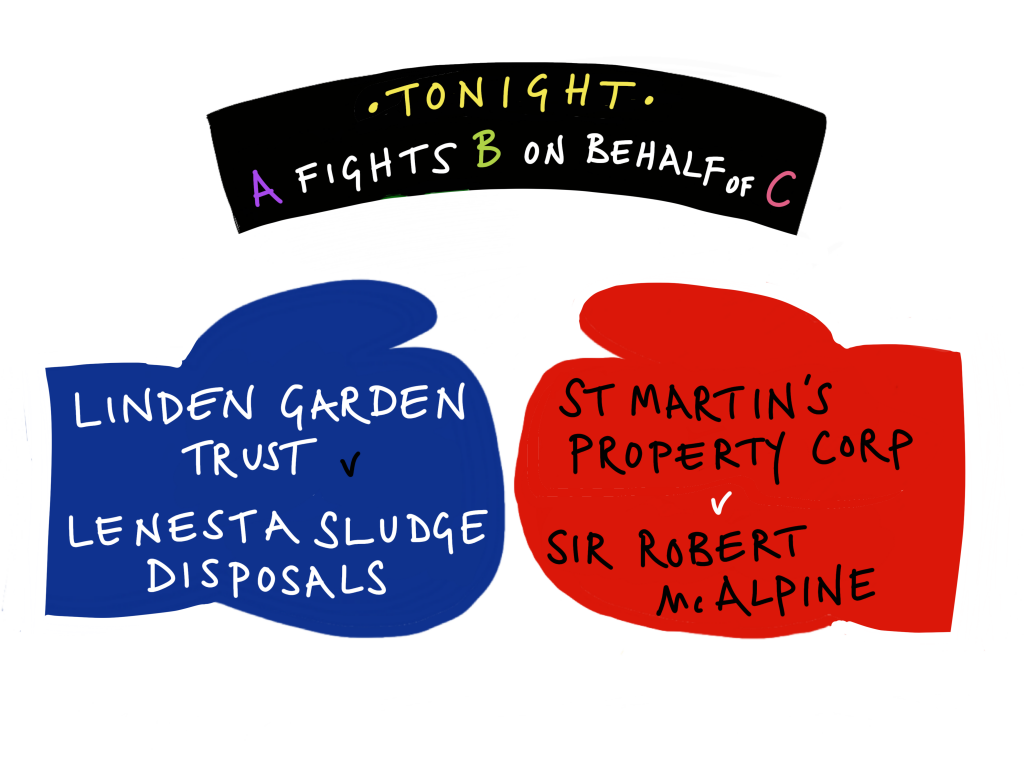

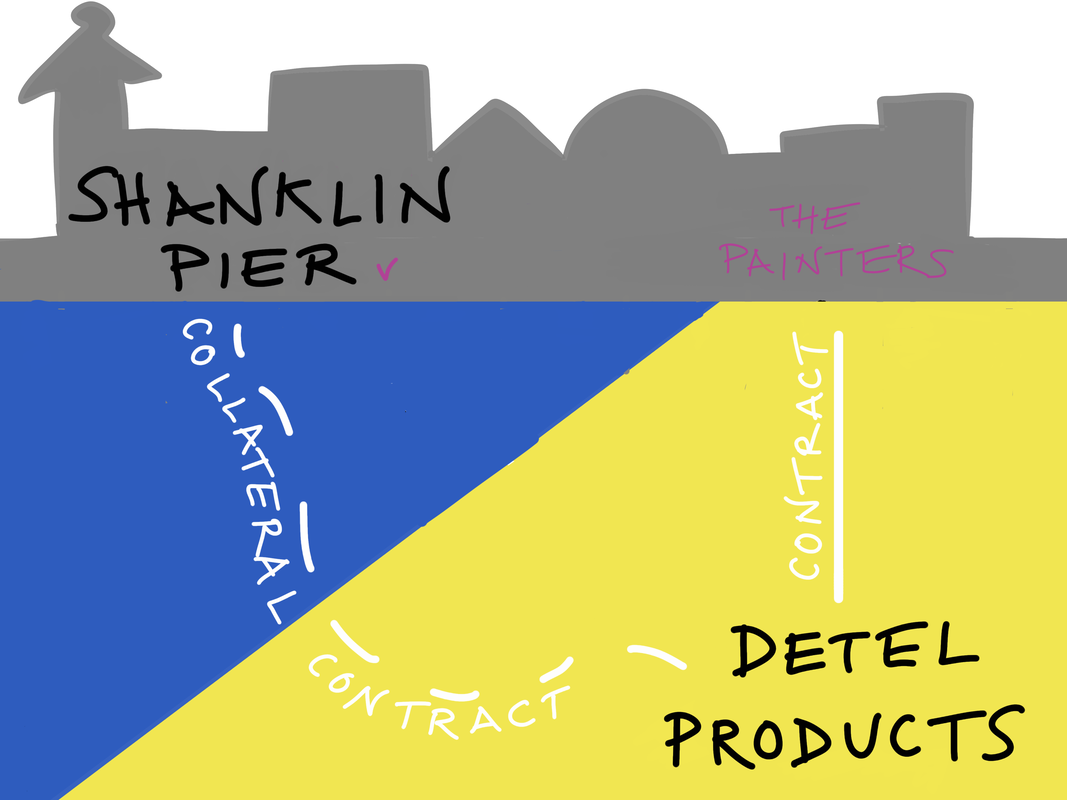

THIRD PARTY: Linden Gardens Trust v Lenesta Sludge Disposal and St Martin’s Property Corp v Sir Robert McAlpine | The Albazero | McAlpine v Panatown | Shanklin Pier v Detel Products | White v Jones | Farrow v Wilson

REVISE | TEST

PRIVITY OF CONTRACT

The doctrine of privity is a common law principle which stops any contractual benefits or obligations being applied to third parties, i.e. someone not party to the initial agreement. A third party has provided no consideration so they cannot be a party to the contract. This is linked to the rule that consideration must move from the promisee, excluding third parties from claiming contractual rights.

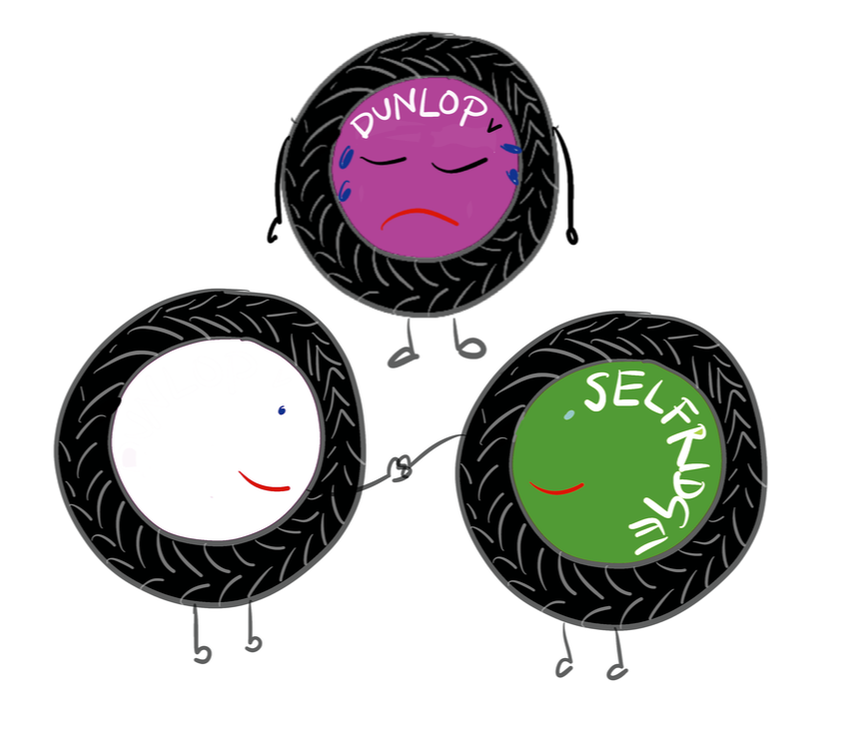

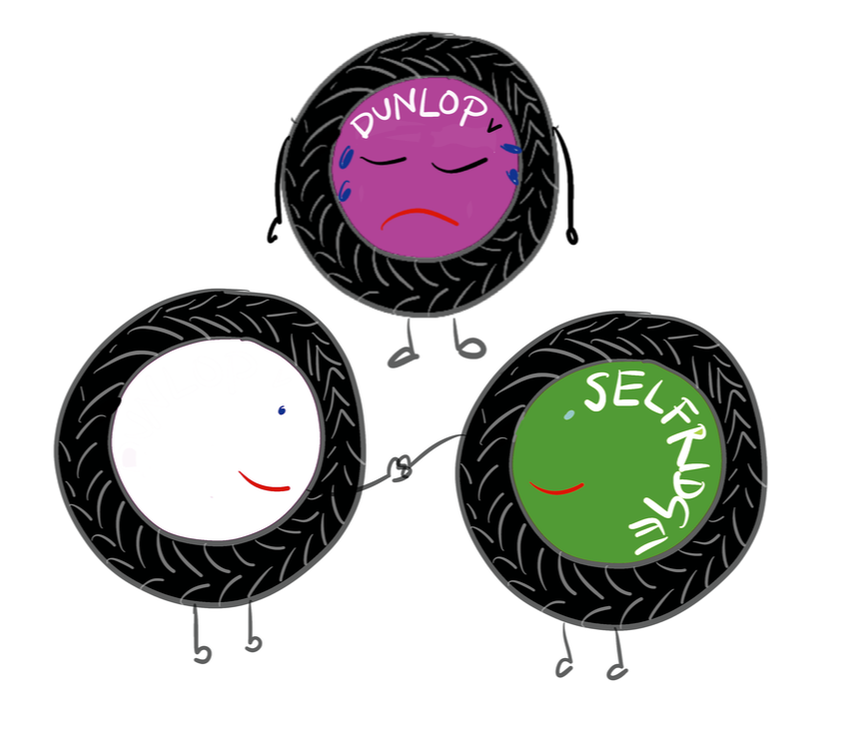

The general rule was confirmed in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyres Co Ltd v Selfridge and Co Ltd (1915) (HoL).

Dunlop sold tyres to Dew & Co. Their agreement stipulated that Dew & Co could not resell them below a certain retail price. Dew & Co then sold some of the tyres on to Selfridge with the same stipulation. When Selfridge sold the tyres on for a lower price than allowed Dunlop sued. The problem was that Dunlop had no contractual relationship with Selfridge as Selfridge had bought the tyres from Dew & Co. The court held that Dunlop could not sue as no consideration had moved from Dunlop to Selfridge (excluding them from being a party to the contract under the consideration rule).

A third party has provided no consideration so they cannot be a party to the contract. This is linked to the rule that consideration must move from the promisee (Tweddle v Atkinson (1861)), excluding third parties from claiming contractual rights.

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULE

There are a number of problems caused by this principle. Namely it thwarts the intention of A and B when they want their contract to give C a right. Even if a contract heavily implies that parties intend for a third party to have enforceable rights this is ignored by the doctrine. Therefore various exceptions to this rule have arisen.

STATUTE

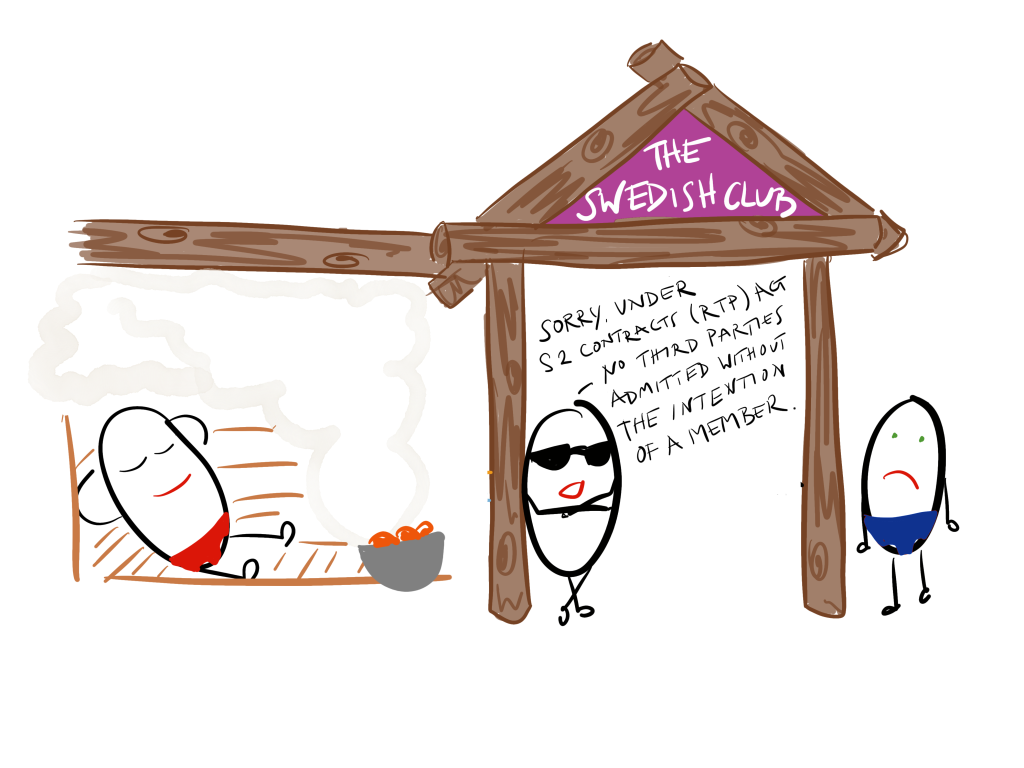

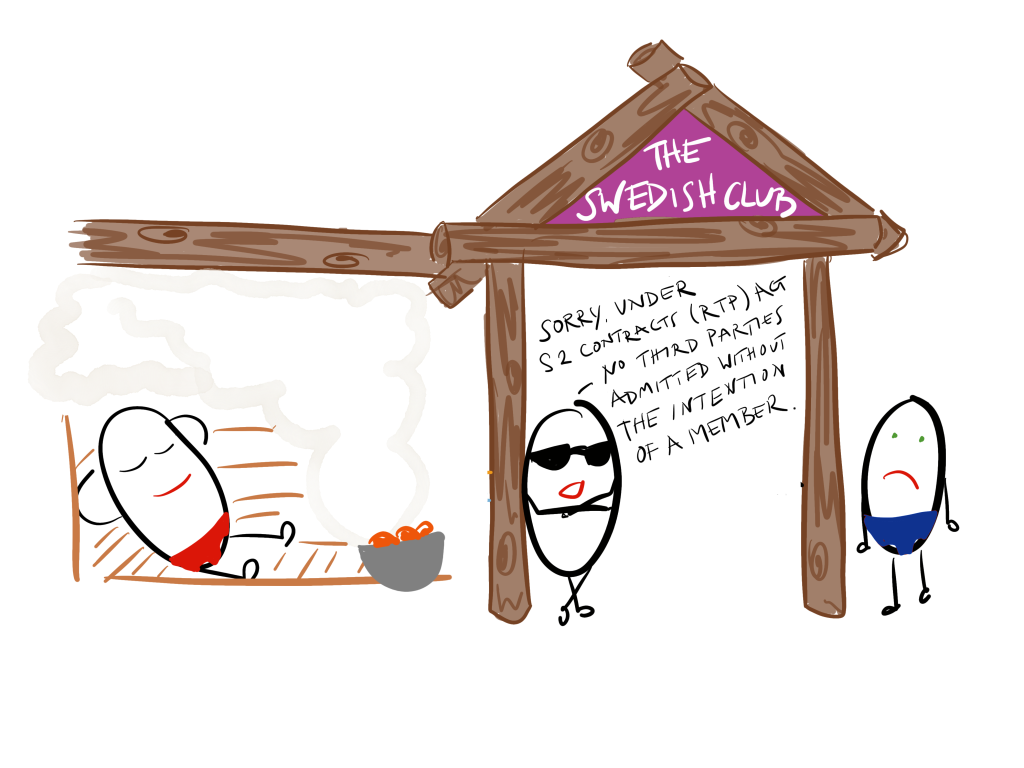

The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 creates an exception to this rule.

|

Section 1(1) states that a third party can enforce terms of an agreement they were not initially party to, where:

- (a) the contract expressly provides that he may, or

- (b) subject to subsection (2), the term purports to confer a benefit on him.

|

Section 1(2) states that the third party will not be able to enforce a term if it can be shown that the parties did not intend them to have that right.

|

Section 1(1)(b) and 1(1)(2) seem to cancel each other out but the case below demonstrates how they work in practice.

In Dolphin Maritime & Aviation Services Ltd v Sveriges Angfartygs Assurans Forening (The Swedish Club) (2009) (HC) an insurance company hired the claimant to recover money owed to it from the defendant. However, the defendant settled directly with the insurers rather than via the claimant’s demand for repayment. The claimant sued the defendant for loss of commission. The court held that the agreement was between the defendant and the insurers, the claimant was a third party, and as this agreement did not intend to confer any legal benefit upon the claimant (even though in reality they would have gained a benefit, the commission) the statute did not apply and the claimants could not sue.

In addition s.1(3) states that in order for a third party to have an enforceable right they must be expressly identified by name, as a member of a class or as answering a particular description but need not be in existence when the contract is entered into.

In Avraamides v Colwill (2006) (CoA) Avraamides engaged BTC to refurbish his bathroom. BTC was then sold to Colwill and the contract of sale stipulated that any outstanding work must be completed by BTC. The work done by BTC was inadequate so Avraamides sued Colwill as the new owner. However, because the agreement between BTC and Colwill did not expressly identify Avraamides as a third party he had no right to sue Colwill.

Additionally, s.1(4) states that the entitlement of a third party to enforce a contractual right must comply with all the other terms of the contract. E.g. where there is a limitation clause contained within the contract, assertion of rights by any third party must take place within the specified time frame, otherwise it will not be valid.

Note that this statute does not change the general rule that a third party cannot be held liable for a contract that they’re not a party to.

CONTRACTS ON BEHALF OF A GROUP

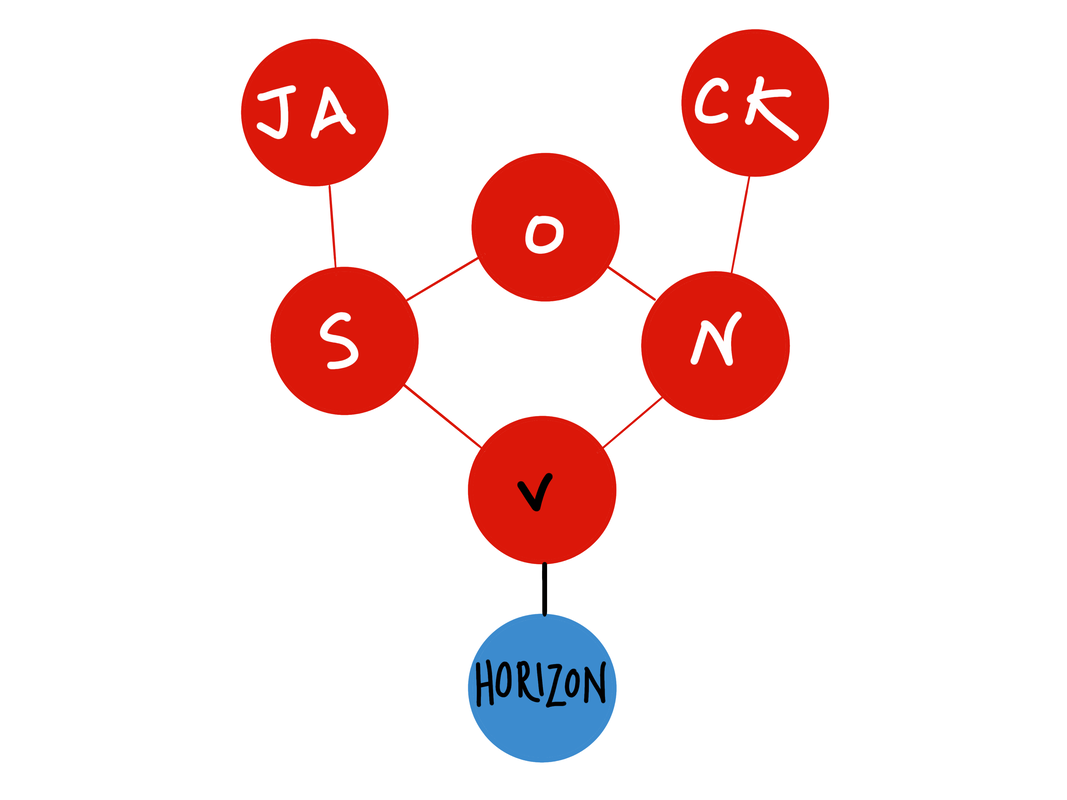

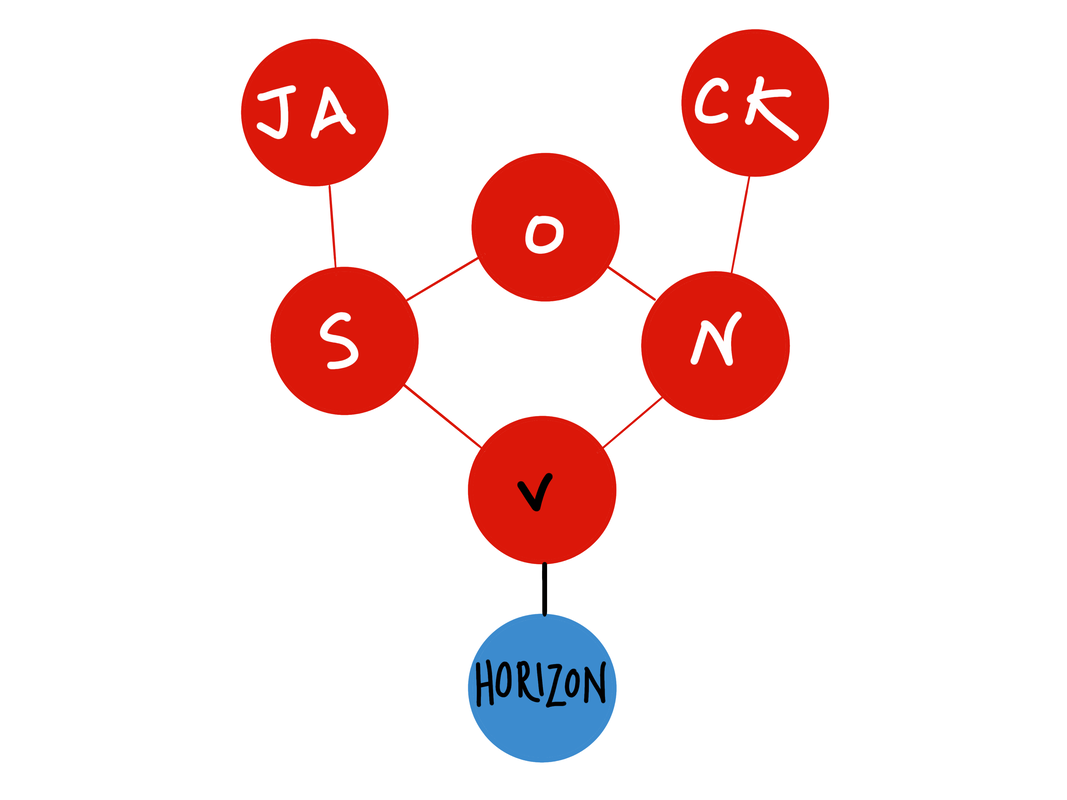

If one party has contracted on behalf of a group then they may be able to recover damages for the whole group (Jackson v Horizon Holidays (1975) (CoA)).

Jackson had booked a holiday for his family. The holiday was terrible, considerably worse than what had been advertised. He sued the holiday company and was awarded almost the whole cost of the holiday. The company appealed on the grounds that Jackson could only recover damages for himself not the other members of the family. The Court of Appeal disagreed; Lord Denning MR argued that Mr Jackson had contracted on behalf of the family and could recover their damages.

This ruling was criticised but not overruled in Woodar v Wimpey (1980) (HoL) and confined to certain types of contract, for example family holidays, restaurant table bookings, hiring a taxi for a group.

CONTRACTS ON BEHALF OF A THIRD PARTY

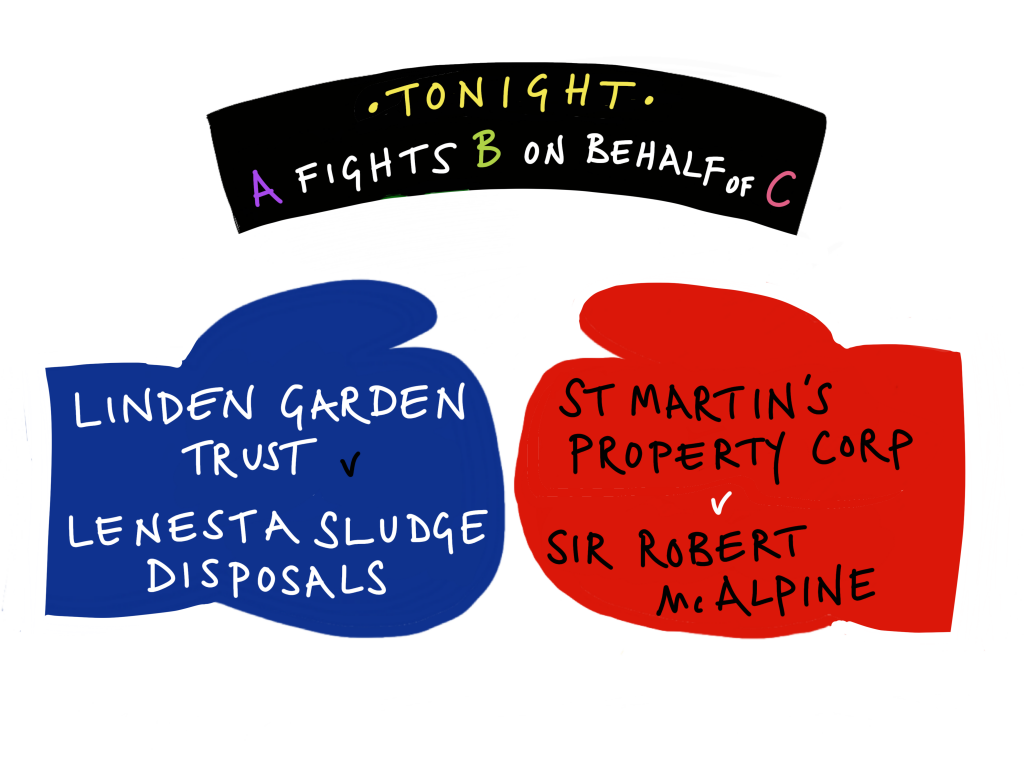

If parties contract in the knowledge that the end benefit of that contract will be held by a third party then one of the original parties can sue on behalf of the third party. This principle was adapted from the shipping case The Albazero and used in two property cases that were heard together, Linden Gardens Trust v Lenesta Sludge Disposal and St Martin’s Property Corp v Sir Robert McAlpine (1994) (HoL).

Both cases concerned one party (A) being employed by another (B) to carry out works on a property that they both knew would then be owned by a third party (C). The work done by A was defective but this was only discovered once the property was owned by C. In the Linden Gardens case C brought a case directly against the other party and failed because the original agreement between A and B had excluded assigning any rights to a third party. Whereas in the St Martin’s Property case C was successful because B sued A on C’s behalf, circumventing the exclusion of assignment to C.

This principle was refined in the case of McAlpine v Panatown (2001) (HoL). Third parties that have another legitimate means of recourse against the original party (in this case a separate duty of care deed) are excluded from relying on The Albazero principle.

COLLATERAL CONTRACTS

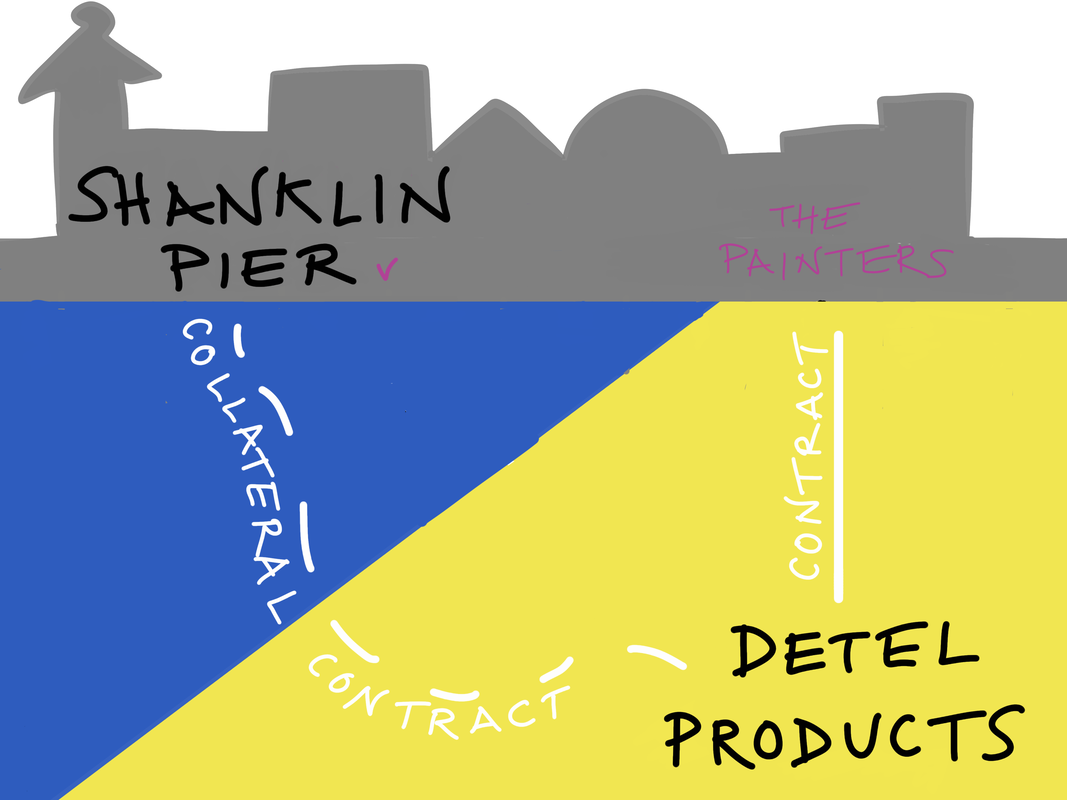

A collateral contract can give rise to third party contractual rights (Shanklin Pier v Detel Products (1951) (HC)).

Shanklin Pier had been persuaded by Detel Products to use their paint for refurbishment of the pier. Detel claimed that the paint would last at least seven years. Shanklin Pier hired a firm to paint the pier and told them to use Detel paint. When the paint started peeling after three years Shanklin Pier sued Detel Products. They were able to do this even though they were technically a third party to the contract between Detel and the painting firm because a collateral contract existed between them. Detel had promised that the paint would last at least seven years and in return Shanklin had instructed the painters to use Detel paint, this was considered sufficient consideration.

OTHER EXAMPLES

TORT

A third party can recover damages if there is a legally recognised duty of care owed to them (White v Jones (1995) (HoL)). White requested his lawyer Jones to change his will in favour of his two daughters. Jones delayed for so long that White had died before it was changed. White’s daughters sued Jones and won because the court found that he owed them a duty of care.

ASSIGNMENT

If A has contracted with B, B can chose to assign their contractual rights to C. However, C is strictly limited to what was agreed between A and B, their newly assigned rights do not go beyond this. Usually this can be done without consent of the other original party. Contracts with a personal element cannot be assigned, i.e. if one party’s duties would be difficult for a third party to fulfil (Farrow v Wilson (1869)).

|

AGENCY

One party (the Principle) can authorise another party (the Agent) to contract on their behalf. The Agent has the power to act in any way on behalf of the Principal, including signing documents, attending meetings, negotiating new contracts and writing letters to suppliers in a commercial context. The Principle is contractually bound by the actions of the Agent. Although the Principle is a kind of third party to the contract this is not necessarily an exception to the privity of contract doctrine as the Principle can still sue and be sued on the contract.

|