JUMP TO: SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE – Sky Petroleum v VIP Petroleum | Société des Industries Metallurgiques SA v Bronx Engineering | Beswick v Beswick | Page One Records v Britton | Hill v CA Parsons & Co | Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores – INJUNCTIONS – Lumley v Wagner | Warner Bros Pictures Inc. v Nelson | Page One Records v Britton | Priyanka Shipping Ltd v Glory Bulk Carriers | Jaggard v Sawyer – RESCISSION – Long v Lloyd | Car and Universal Finance v Caldwell | Leaf v International Galleries | Clarke v Dickson | Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co | Salt v Stratstone

EQUITABLE REMEDIES

There are a number of other remedies, apart from damages, available in a breach of contract claim. These are equitable remedies, awarded at the discretion of the court and subject to the laws of equity so will only be awarded when it is fair and equitable to do so. They are not subject to the rules of remoteness and mitigation.

In general these remedies will be awarded when damages would be inadequate. An award of damages remains the primary remedy in contract law and is available as a right; whereas equitable remedies are not always available when sought.

SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE

Specific performance forces a party to perform their existing contractual obligations. The benefit of obtaining such a court order is that the defendant will be in contempt of court if it fails to abide by the order. It will only be granted if damages would not provide an adequate remedy. This can be for several reasons…

UNIQUENESS

If the subject of the contract is so unique that the claimant would not be able to buy a substitute with damages.

Even if the subject of the contract is not in itself unique, the circumstances of the case may make it difficult for the innocent party to acquire a substitute (Sky Petroleum v VIP Petroleum (1974) (HC)).

Sky had contracted with VIP to buy petrol and diesel. VIP tried to terminate the contract during a worldwide petroleum shortage so even though the products were not in themselves unique, Sky would have struggled to find alternatives at an equivalent price, if at all. There was also a serious risk that the buyer would be forced out of business if it could not obtain oil. The court made an order of specific performance as it found that damages would be inadequate given the circumstances.

In contrast, in Société des Industries Metallurgiques SA v Bronx Engineering Co. Ltd (1975) (CoA) the goods were not considered to be unique and specific performance was not ordered. The buyer had ordered a machine from the seller and, following a dispute, the seller refused to deliver it. The buyer could obtain a substitute machine but only after a 9-12 month delay. The court found that the long delay did not impact the result, that the machine could be substituted and therefore damages were adequate.

CONTRACTS FOR LAND

All contracts for land are automatically deemed unique. This is true no matter how unique, or not, the property is.

|

QUANTIFYING TOO DIFFICULT

Specific performance may be awarded if quantifying damages is too difficult (Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores Ltd (1998) (HoL) see below).

|

DAMAGES NOT COMPENSATORY

If damages would not reflect true compensation, such as if damages were only nominal (Beswick v Beswick (1968) (HoL)).

Mr Beswick had intended that upon his death his heir (a nephew) would pay Mrs Beswick an annual stipend. The nephew failed to do so but Mrs Beswick could not sue him as she was a third party to the contract. The estate, of which she was an executrix, could sue but would only be awarded nominal damages. The court felt that this would not be an adequate remedy for Mrs Beswick so they awarded specific performance, obliging the nephew to continue payments to Mrs Beswick.

RESTRICTIONS TO SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE

There are circumstances in which the courts will not award specific performance.

CONTRACTS FOR PERSONAL SERVICE

A contract for a personal service cannot be subject to an order for specific performance. It would be an infringement of a party’s liberty to force them to perform a personal service they did not want to perform (Page One Records v Britton (1968) (HC)).

The pop group, The Troggs, hired Page One Records as their sole agent and manager for a fixed term of five years. Under the agreement The Troggs could not act for themselves and were prohibited from appointing anyone else as their manager. The Troggs fell out with their manager and wanted to replace him. The manager sought an injunction to force the Troggs to continue with the contract but the court felt that this would be akin to specific performance of a personal service and refused to award one.

Personal service contracts also include employment agreements which are governed by statute. Section 236 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 states that no court shall compel any employee to do any work by ordering specific performance of, or granting an injunction in relation to, a contract of employment. One exceptional circumstance to this general rule was identified in Hill v CA Parsons & Co. Ltd (1972) (CoA).

Mr Hill was 63 years old and had worked for the defendant for 35 years. The defendant entered into a closed shop agreement with a trade union called DATA. This is a type of contract where an employer agrees to only employ workers who are members of a specific union. These types of agreements have been subsequently dismantled by employment legislation but were still lawful at the time of this case. Mr Hill had every expectation that he would continue working for the defendant until he retired. He was not interested in joining DATA and the defendant, at the insistence of the union, proposed to terminate his employment on one month’s notice. The employment relationship had not deteriorated, it was only union pressure that had resulted in Mr Hill’s termination. The court ordered the defendant to continue employing Mr Hill for an additional six months. Although this may seem like a short time, the Industrial Relations Act 1971 was about to come into effect and this would protect Mr Hill further from the closed shop agreement.

UNDULY OPPRESSIVE OR DIFFICULT TO ENFORCE

Specific performance will not be ordered if enforcing the order would create a difficult and on-going issue of enforcement for the parties and the court, or the order would create an unduly oppressive situation for the party having to comply.

In Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd (1998) (HoL) the Co-op leased one of its units in a shopping centre to Argyll for 35 years with a covenant to ‘keep open the demised premises for retail trade’. In 1997 Argyll closed the store because it was losing money and the Co-op sought specific performance to keep the shop open. The trial judge refused to grant the order but the Court of Appeal, by a majority, granted it. The CoA found that the Co-op would have serious difficulty in quantifying their losses and that the defendants had acted with ‘unmitigated commercial cynicism’.

The House of Lords allowed the defendants to appeal this decision. They refused an order of specific performance and agreed with the trial judge. Their Lordships relied on a number of factors in arriving at their decision. They did not want to force the defendant to continue running a business exposing it to potential losses. It would also have been very difficult to enforce the order as the lease was set to run for another 17 years. Argyll may have ended up losing more money if they had been forced to keep the shop open than they would have had to pay in damages, which would have been akin to a punitive measure. It was also against the public interest to require someone to carry on a business at a loss and it was oppressive to the defendants to run a business under the threat of being in contempt of court.

INJUNCTIONS

PROHIBITORY INJUNCTIONS

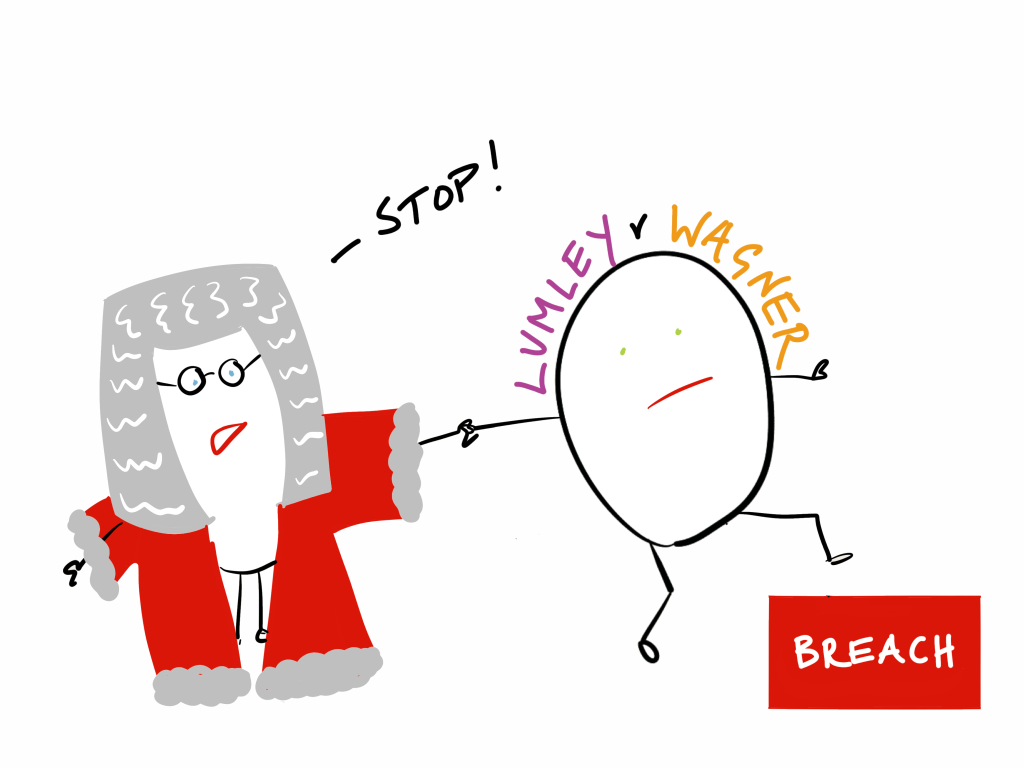

This type of injunction prevents or restricts the defendant from committing a future breach of a negative contractual stipulation, e.g. that they cannot work for another company (Lumley v Wagner (1852) (HC)).

The defendant was an opera singer who was contracted to perform in Lumley’s theatre for three months. The contract contained an express provision which prevented Wagner from singing in other concerts during that time. When the defendant was offered a higher wage to sing at a competitor’s theatre, the claimant sought an injunction preventing the defendant from doing so.

Although the injunction was akin to indirect specific performance of a personal service (i.e. forcing her to perform for Lumley) it was successfully granted because theoretically she could find employment other than singing.

The same approach was followed in Warner Bros Pictures Inc. v Nelson (1937) (HC) where Mrs Nelson, professionally known as Bette Davis, had contracted to render her services exclusively to Warner Bros for a certain period of time. She breached that agreement by rendering her services to a third party. Although an injunction would have had the same effect as an indirect order of specific performance for personal services, an injunction could be granted to enforce a negative contractual covenant. Mrs Nelson could still earn a living without breaching the negative covenant. This was perhaps more extreme than the Lumley case as Lumley was only for a period of three months, but Mrs Nelson would be prevented from working for anyone else for a number of years.

However, the more recent case of Page One Records v Britton (1968) (HC) (see above for details) presents a more realistic approach to indirect specific performance through injunctions. The injunction was not awarded as the court felt that imposing an injunction on The Troggs to force them to work with Page One Records was akin to indirect specific performance of a personal service even though technically they could have continued without a manager at all or disbanded and found other jobs.

NEGATIVE COVENANTS

Prohibitory injunctions do not only apply to restraint of trade clauses but can apply to all negative contractual obligations, also known as negative covenants. In Priyanka Shipping Ltd v Glory Bulk Carriers Pty Ltd (2019) (HC) the buyer purchased a vessel from the seller for scrap purposes and they agreed that they would not ‘trade the Vessel further’. The seller wanted the vessel decommissioned as there was an oversupply of carriers on the spot market and it had a commercial interest in the vessel not trading again. However, the buyer found it difficult to sell the vessel for demolition and decided instead to continue using the vessel for trade purposes. This effectively breached its undertaking under the contract. The seller sought an injunction to stop the vessel from trading and breaching the covenant further. The court found that the seller was entitled to an injunction. The buyer had to satisfy the court that the ordinary position should not apply because it would be unconscionable or oppressive for an injunction to be granted. On the evidence, the buyer came nowhere close to illustrating that this was the case.

MANDATORY INJUNCTIONS

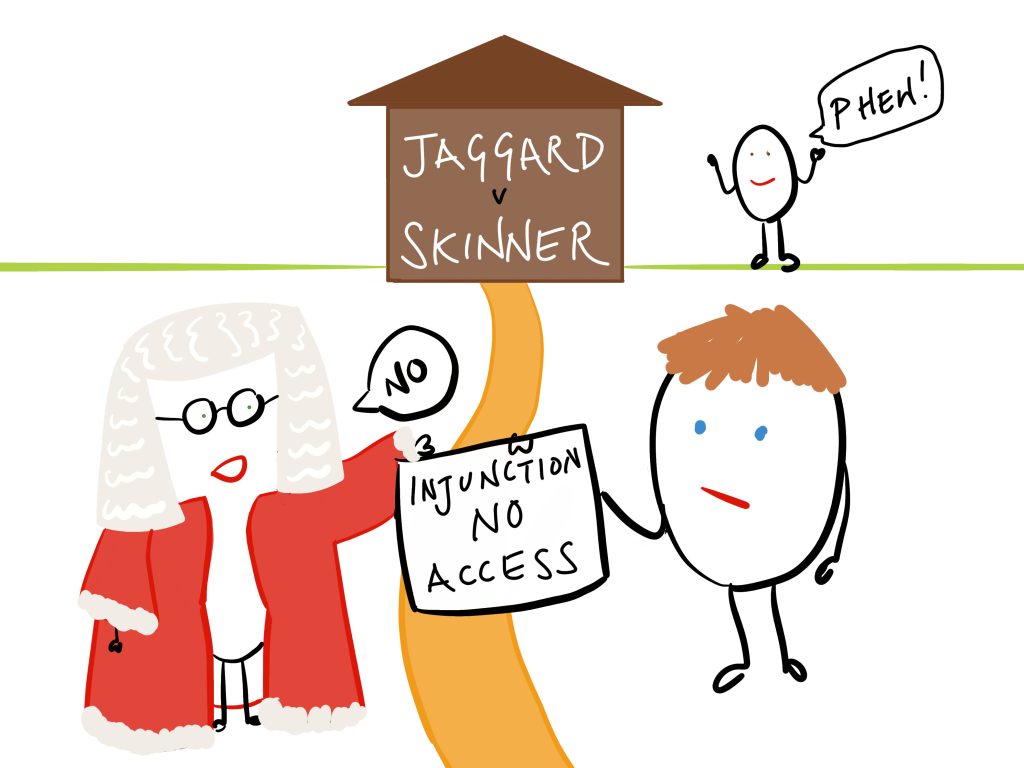

This type of injunction imposes a duty on a party to do something and is used to remedy a breach that has already happened. They are subject to the same stipulations as orders for specific performance (see above). They are subject to the ‘balance of convenience’ test which weighs up how convenient or inconvenient it would be for each party if the injunction was ordered.

As with specific performance the courts will not grant an injunction which would be too oppressive for the respondent. In Jaggard v Sawyer (1995) (CoA) the respondent had built a property that could only be accessed by breach of a restrictive covenant. The court refused to grant an injunction that would have prevented him from accessing his property because it would have been too unnecessarily oppressive on the respondent’s legal rights.

RESCISSION

This is an equitable remedy awarded at the discretion of the court whereby the contract is set aside (made void) and the parties are returned to the position that they would have been in had the contract not been entered into.

Rescission is available where a contract is voidable as a result of a vitiating factor such as misrepresentation, undue influence or duress. The party wishing to rescind the contract must communicate this to the other party. Remember that ‘voidable’ is different to ‘void ab initio’ which occurs when a fundamental mistake is proven. See Mistake.

BARS TO RESCISSION

Rescission cannot be awarded if any of the following situations occurs…

| CLAIMANT AFFIRMS THE CONTRACT |

3rd PARTY ACQUIRES RIGHTS |

LAPSE OF TIME |

RESTORATION IS IMPOSSIBLE |

CLAIMANT AFFIRMS CONTRACT

The claimant will lose their right to rescind if they affirm the contract (Long v Lloyd (1958) (CoA)).

Long agreed to purchase a defective lorry from Lloyd if Lloyd paid half the costs of repair. Subsequently, further defects were discovered with the lorry but Long continued to use it for business trips. When he tried to rescind the contract on the grounds of innocent misrepresentation it was held that he had lost the right to rescind when he continued to use the lorry thereby affirming the contract.

3RD PARTY ACQUIRES RIGHTS

A party will not be able to rescind if the goods in question have already been acquired by a third party. For example, in mistaken identity cases such as Phillips v Brooks (1919) (HC) in which the goods are acquired by a ‘rogue’ and then sold onto a third party before the innocent party has time to rescind (see Mistake).

In Car and Universal Finance v Caldwell (1965) (CoA) Caldwell sold a Jaguar to a rogue named Mr Norris. When he discovered that he had been paid with a fraudulent cheque he was unable to find Mr Norris to communicate that he wanted to rescind their contract for the sale of a car on the basis of mistaken identity. Mr Norris had, by this point, sold the car onto car dealers called Car and Universal Finance Ltd who bought the vehicle in good faith. The question was whether Caldwell had validly rescinded before the car was acquired by a bona fide purchaser for value without notice? It was shown that Caldwell’s actions – contacting the police and the AA – which took place before Norris sold the car on, were sufficient to rescind.

LAPSE OF TIME

As rescission is an equitable remedy an action for rescission must be brought without delay, as delay defeats equity. If a party takes too long to communicate rescission then this may be seen as affirmation of the contract (Leaf v International Galleries (1950) (CoA)).

Leaf bought a painting from International Galleries believing it to be by the painter Constable. When he discovered five years later that it was not by the famous artist he tried to rescind the contract for misrepresentation but was barred from doing so because of the lapse of time.

RESCISSION IS IMPOSSIBLE

Rescission cannot be granted if it would be impossible to return the parties to their pre-contractual positions (Clarke v Dickson (1858) (HC)).

Clarke entered into a contract for shares in a lead and copper mining partnership. The partnership became a limited liability company (without shareholders) and subsequently went into liquidation. Clarke tried to reclaim his money because the statements that had induced him to enter into the contract turned out to be false. However, because the company no longer existed it was impossible for him to return his shares and be returned to the position he had been in before the contract.

The subject of the contract does not have to be completely unchanged in order to be returned to the other party, as long as it is substantially the same (Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co. (1878) (HoL)). A phosphate mine that had been worked, but not exhausted, was returned along with the profits made from working the mine. This was deemed the equivalent of returning the mine as it had been before the contract. As an equitable remedy it is at the judges’ discretion to do what they think most fair. Also see Salt v Stratstone (2015) (CoA).