JUMP TO: OCCUPIER | PREMISES | LAWFUL VISITORS | TRESPASSERS | STANDARD | DISCHARGING A DUTY | DEFENCES | REVISE | TEST

OCCUPIER’S LIABILITY

Occupiers’ Liability covers injuries that occur due to the state of the premises or to things done or omitted to be done on them (rather than injuries resulting from activities carried out by the visitor whilst they are on the premises). It is governed by the basic rules of negligence and statute.

Take for example the case of Keown v Coventry Healthcare NHS Trust (2006) (CoA). An 11 year old boy injured himself when playing on a fire escape ladder in the grounds of a hospital. In the first instance the judge found against the defendant but the decision was overruled by the Court of Appeal. Justice Lewison stated: ‘The threshold question is not whether there is a risk of suffering injury by reason of the state of the premises. It is whether there is a risk of injury by reason of any danger due to the state of the premises. Thus in order for the threshold question to be answered in the affirmative it must be shown that the premises were inherently dangerous.’

|

Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957

- covers lawful visitors

- automatic duty of care to lawful visitors

- covers physical injury and property damage

|

Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984

- covers unlawful visitors, i.e. trespassers

- a duty of care must be established based on specific criteria

- only covers physical injury not property damage

|

OCCUPIER

The occupier is not automatically the party that owns the building it is the party that has a sufficient degree of control over the property that they should owe a duty of care to anyone coming onto the property (OLA 1957 s.1(2)). Wheat v Lacon (1966) (HoL) set out the different types of occupier who might have the requisite control over a property;

- a tenant will be the occupier if the landlord does not live in the property,

- the landlord will be occupier of any common areas such as staircases,

- if the property is licensed by the landlord they will remain as occupiers (this was the case in Wheat v Lacon (1966)),

- the occupier will generally remain liable if they bring an independent contractor onto the land.

This duty can be shared by several parties (Wheat v Lacon (1966) (HoL)). Mr Wheat died after falling down a set of narrow, dimly lit stairs in a pub part of which did not have a handrail. The brewery who owned the pub and the couple who licensed the premises from the brewery were all held as occupiers but with varying levels of control over the property and therefore different duties of care to the claimant. Neither were found to have breached any duty of care because it was the darkness that made the stairs dangerous and it had been an unknown third party who had removed the lightbulb shortly before Mr Wheat had used the stairs.

If they are deemed to have sufficient control over the property a party can be the occupier even if they have never physically occupied the property. In Harris v Birkenhead Corporation (1976) (CoA) a child fell from the window of a derelict building owned by the local council. Even though they have never been to the property they exercised sufficient control to have a legal duty of care to make it safe for visitors.

CONTROL OVER ACCESS

Just because a party may have control over the means of access does not mean that they have control over the premises itself. In Bailey v Armes (1999) (CoA) the defendants lived in an apartment above a supermarket. Their son and his friend were allowed to play on the flat roof of the supermarket, accessible from their window. Most of the roof was walled but the section furthest from the window was not. The children accessed this area and the friend fell off and injured himself. The defendant, although they allowed access to the roof, did not have sufficient control over the roof to be deemed occupiers and were therefore not liable.

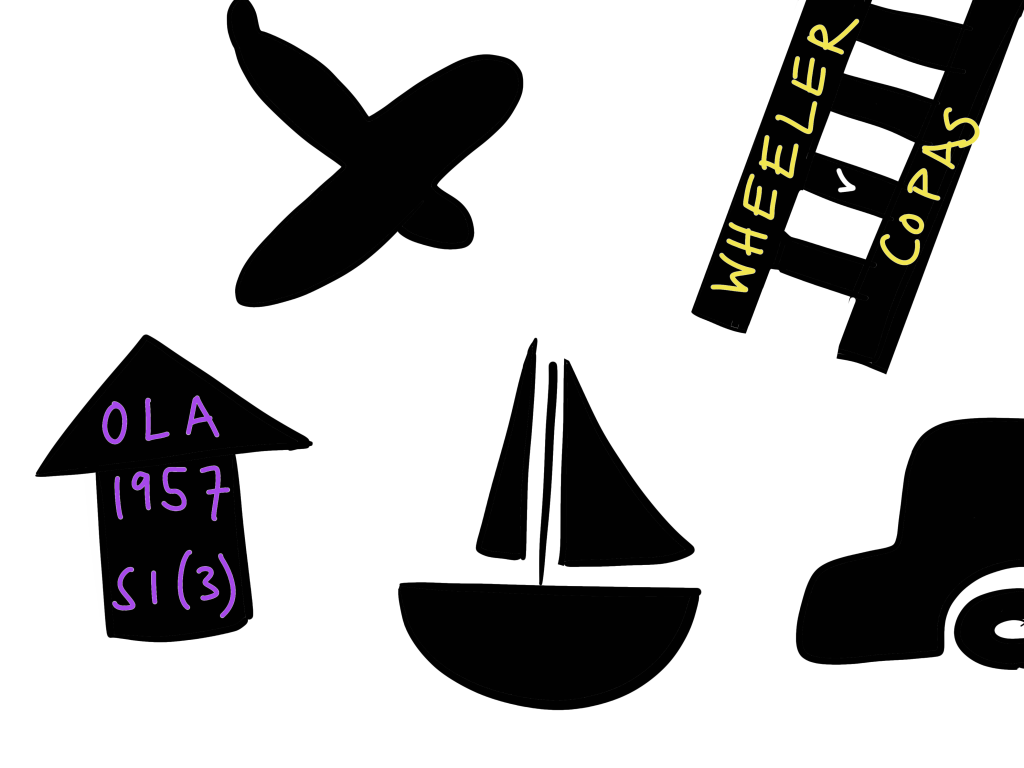

PREMISES

The definition of premises is very wide, including all land and buildings plus ‘any moveable structure, including any vessel, vehicle or aircraft’ (OLA 1957 s.1(3)). For example, in Wheeler v Copas (1981) (HC) ‘premises’ included a ladder.

LAWFUL VISITORS – OLA 1957

Under the OLA 1957 s.1(2) the occupier only owes a duty of care to those who have been given permission to be on the premises, a lawful visitor. This permission can be express or implied and it can be restricted by area, time or purpose.

Visitors with lawful authority to be on the premises – such as police officers with a warrant – do not need the express permission of the occupier.

RESTRICTION BY AREA

A visitor can be lawful in one area of a property but not others. If the occupier wishes to restrict a lawful visitor by area this must be made clear (Pearson v Coleman Bros (1948)).

A child was attacked by a circus animal when she found her way into the animal enclosure. Although she shouldn’t have been in the enclosure there were no signs or notices telling her that she did not have permission to enter. Therefore the court held her to be a lawful visitor and the occupier was liable for her injury.

RESTRICTION BY TIME

Restrictions by time must be made equally clear to the visitor. In Stone v Taffe (1974) the claimant fell down some stairs in a pub. They were there after hours so the defendant tried to argue that they were not a lawful visitor. However, the claimant was a lawful visitor because they had not been made aware of this time restriction by the occupier.

RESTRICTION BY PURPOSE

An occupier can restrict a visitor by what they are allowed to do on the premises. Just because someone has permission to be on the premises does not mean that they have been given a blanket permission to behave as they wish. As Scrutton LJ stated in The Carlgarth (1927) (CoA); ‘When you invite a person into your house to use the staircase, you do not invite him to slide down the bannister.’

CHANGE OF PURPOSE

A lawful visitor can become a trespasser depending on their behaviour (R v Jones and Smith (1976)).

The defendants turned themselves from lawful visitors, at one of their parent’s home, into trespassers by trying to steal a TV.

IMPLIED PERMISSION

The occupier can give implied permission to visitors to access the premises. This will depend upon the behaviour of the occupier. The burden of proof rests on the person claiming implied permission (Lowery v Walker (1911) (HoL)).

The public had been using a short cut over private land for over thirty years. When the claimant was attacked by a horse on the land the defendant argued that they did not in fact have permission to be on the land. The court held that because of the long established use of the short cut that implied permission had been given by the occupier.

However, implied permission only covers specific activities, e.g. walking across the land. In Harvey v Plymouth City Council (2010) (CoA) a man tripped on council land when he was running away from a taxi without paying. The council had given implied permission to the public to use the land but only for foreseeable recreational activities, not for running away from a taxi without paying.

REVOCATION OF PERMISSION

The occupier can revoke a visitor’s permission whilst the visitor is on the premises. However, in Snook v Mannion (1982) (HC) telling a police officer to ‘f**k off’ whilst being pursued up a private driveway was not sufficient to revoke the implied permission given to visitors approaching a house on legitimate business.

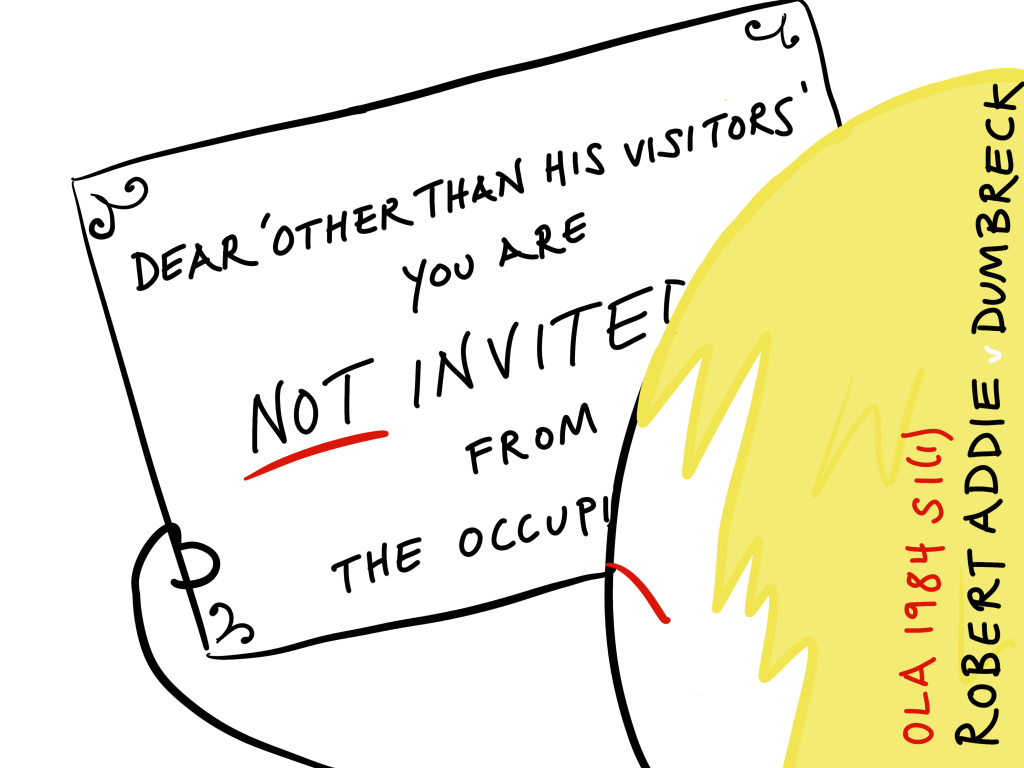

TRESPASSERS – OLA 1984

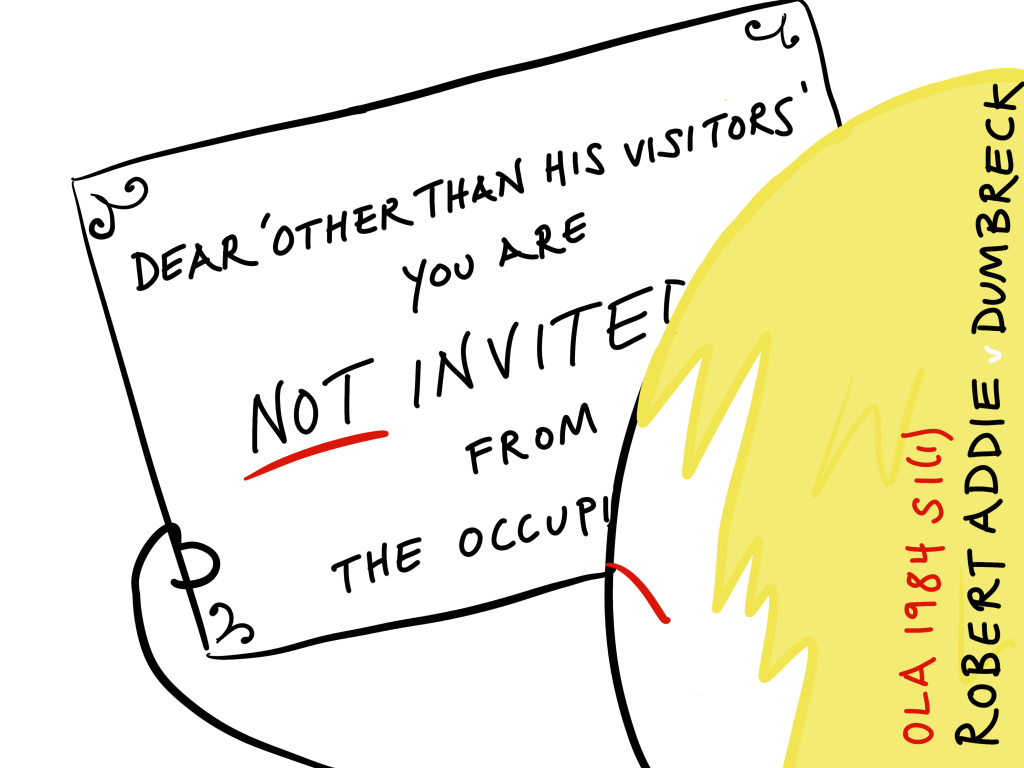

The OLA 1984 covers uninvited visitors, in other words trespassers. In s.1(1)(a) they are defined as ‘other than his visitors’. A trespasser is ‘he who goes on to the land without invitation of any sort and whose presence is either unknown to the proprietor or, if known, is practically objected to.’ Lord Dunedin, Robert Addie & Son v Dumbreck (1929) (HoL).

DUTY OF CARE – OLA 1957

Under the OLA 1957 an occupier owes an automatic duty of care to a lawful visitor.

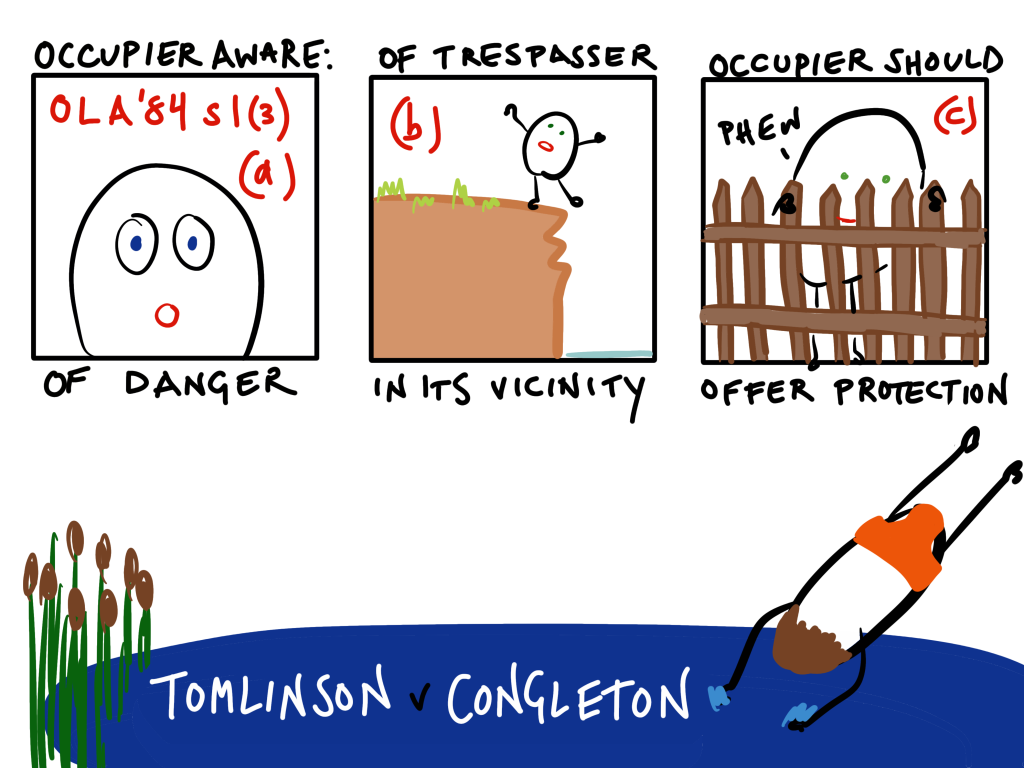

DUTY OF CARE – OLA 1984

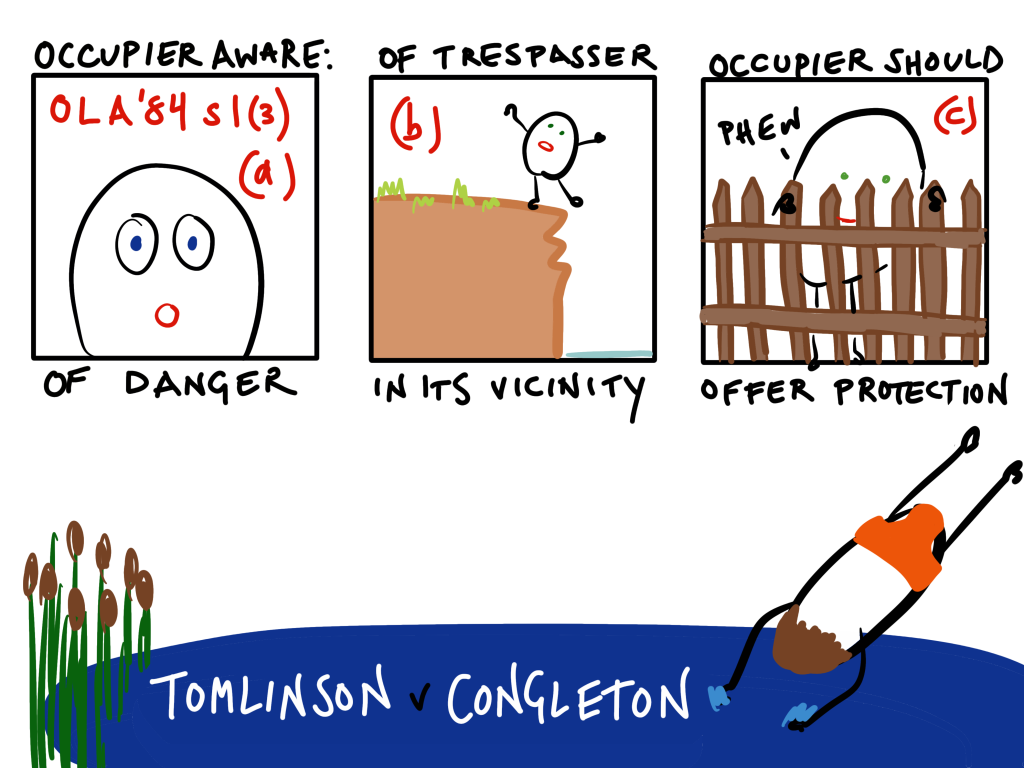

Under the OLA 1984, in order for an occupier to owe a duty of care to a trespasser, several criteria must be met.

s.1(3)(a) The occupier is aware of the danger or has reasonable grounds to believe that it exists;

s.1(3)(b) The occupier knows or has reasonable grounds to believe that someone is in the vicinity of the danger concerned or that may come into the vicinity of the danger (whether or not that person has lawful authority for being in that vicinity); and

s.1(3)(c) the risk is one against which, in all the circumstances of the case, the occupier may reasonably be expected to offer the unlawful visitor some protection.

The case of Tomlinson v Congleton Borough Council (2003) (HoL) illustrates this well. Tomlinson paralysed himself when he hit his head doing a shallow dive into a lake. The lake was managed by the council. There were signs warning people against swimming and park rangers who told people not to swim, but often people swam anyway. The council was planning to plant vegetation around the edge of the lake to dissuade swimmers but had not done so yet because of budget restraints. Tomlinson was a visitor on the land but immediately classed as a trespasser when he entered the water because the occupier had restricted permission by area by telling visitors not to go into the lake. The court held that the council did not owe Tomlinson a duty of care; the accident had not occurred because of a risk posed by the state of the premises, diving into a lake posed inherent risks that would have been the same in any lake, there was nothing particularly dangerous about that lake. Although the council knew of the danger and knew that people were in the vicinity who might be subject to that danger someone making a bad dive into shallow water was not a danger that they could reasonably have protected people from. It was akin to a mountaineer stumbling and falling as they climbed, it was inherent to the activity and the claimant’s responsibility. Even if the 1957 Act had applied the risk was so obvious that the council would not have been expected to warn people about it.

STANDARD OF CARE

As with all negligence claims the occupier will be held to the standard of the reasonable man. All of the normal rules of standard of care and breach apply to cases of occupier’s liability but note that it is the visitor that must be kept reasonably safe and not the premises.

| OLA 1957 s.2(2) ‘a duty to take such care as in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to see that the visitor will be reasonably safe in using the premises for the purposes for which he is invited or permitted by the occupier to be there.’ |

OLA 1984 s.1(4) ‘the duty is to take such care as is reasonable in all the circumstances of the case to see that he does not suffer injury on the premises by reason of the danger concerned.’ |

Although similar what is considered reasonable for a visitor and for a trespasser will probably differ. The courts will still consider all of the normal factors such as cost of avoiding the danger, probability of the danger occurring, seriousness of injury, etc.

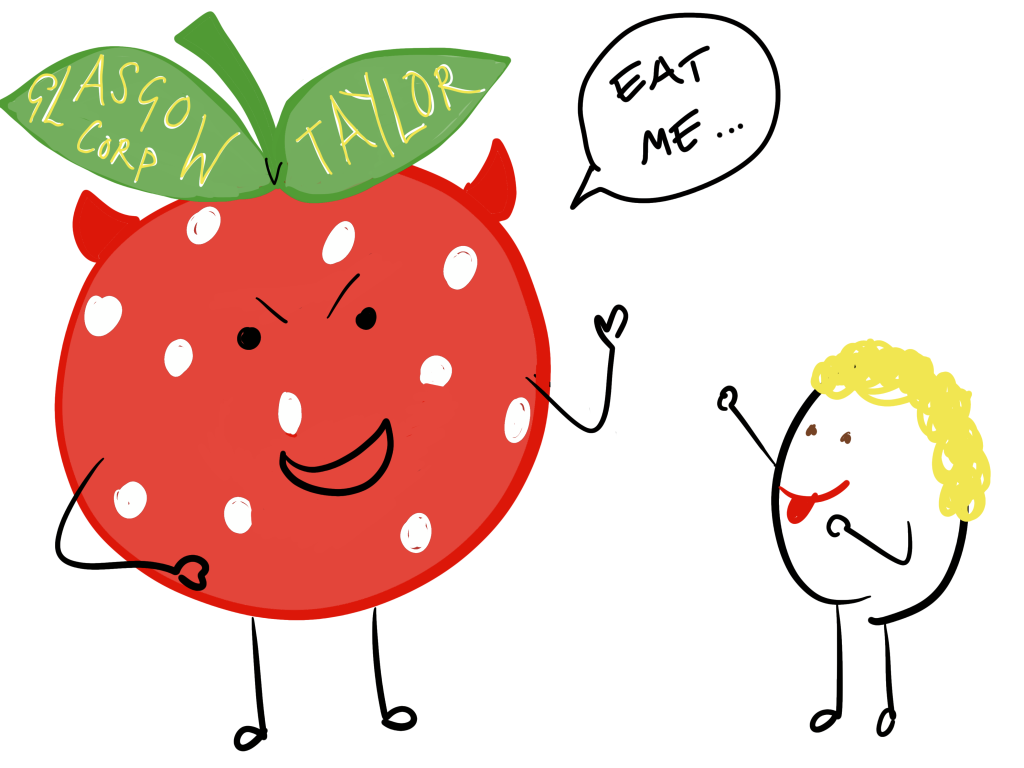

STANDARD OF CARE FOR CHILDREN – ALLUREMENT

Occupiers should be aware that children are often allured onto premises and this should be taken into account when assessing the risks on one’s property (OLA 1957 s.2(3(a)). This also applies to children who are trespassers.

In Glasgow Corporation v Taylor (1922) (HoL) a seven year old died from eating poisonous berries. The court found that the occupier should have identified this as a particularly alluring risk to children and fenced off the bush.

However, parents cannot shift all responsibility to an occupier. In circumstances in which an occupier could have assumed that a child would be accompanied by an adult the standard will be assessed accordingly. In Phipps v Rochester Corporation (1955) (HC) a child fell down a trench on a site being developed by the defendant. The court held that the trench would have been obvious to an adult and it was reasonable for the defendant to assume that children on the site would be accompanied by an adult. Therefore the defendant was not liable. However, a distinction was made between ‘big’ and ‘little’ children; it is more reasonable to assume that a ‘little’ child would be accompanied by an adult.

In contrast, if it is known to the defendants that unaccompanied children are using a certain area this will not apply. In Perry v Butlins Holiday World (1998) (CoA) the court held that the defendants should have foreseen the risk to unaccompanied children in a certain area of the holiday camp which was often used by unaccompanied children.

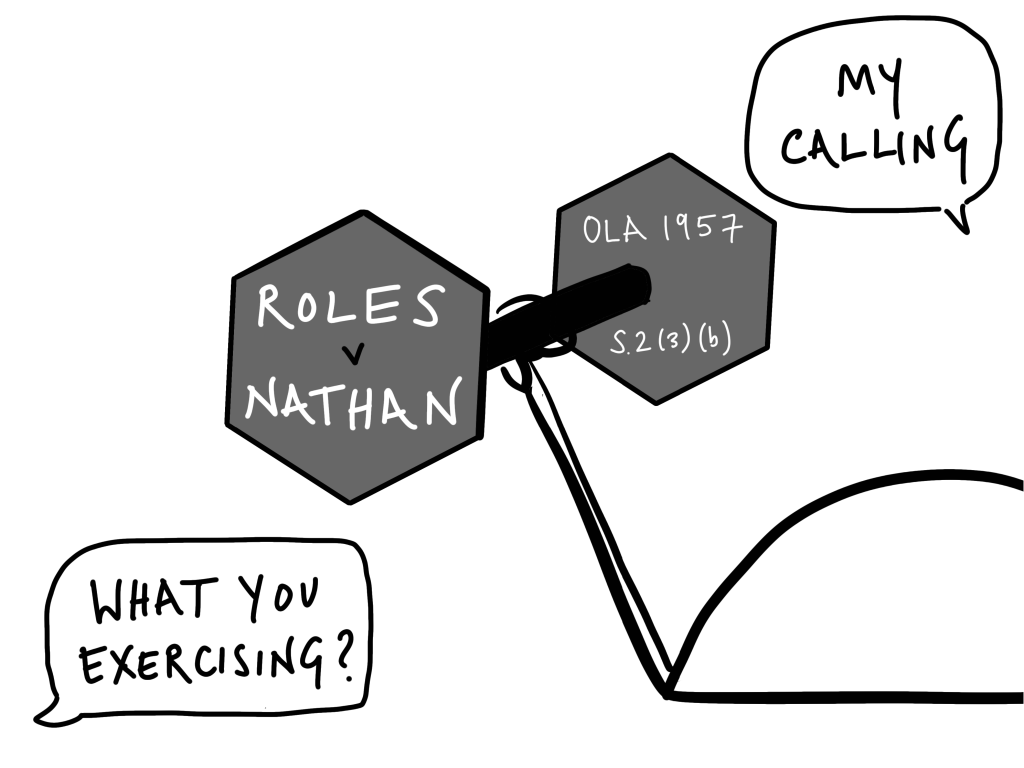

STANDARD OF CARE FOR PROFESSIONALS – EXERCISE OF A CALLING

If a visitor is on the premises to carry out a specific activity or job the occupier is not liable for risks that are inherent to that job. This is set out in OLA 1957 s.2(3)(b).

In Roles v Nathan (1963) (CoA) two chimney sweeps died of monoxide poisoning when cleaning out the flue of a boiler. They had been warned of the danger but failed to turn off the boiler whilst they were working. The occupier was not liable as the claimants had been on the premises in exercise of a calling, this was an inherent risk of that calling and the claimants had been warned about this risk by the defendant.

In contrast, in Salmon v Seafarer Restaurant (1983) (HC) and Ogwo v Taylor (1957) (HoL) firemen were injured fighting fires. They had taken all possible precautions but were injured because of the occupier’s negligence. Therefore the occupier was still liable even though they had entered the premises in exercise of a calling.

DISCHARGING A DUTY OF CARE

INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS

Independent contractors can be occupiers if they have a sufficient degree of control over the property, or a part of the property, and the occupier acted reasonably in entrusting them with this control (OLA 1957 s.2(4)(b)). The occupier must show that it was reasonable to hire an independent contractor (i.e. the difficulty of the work), it was reasonable to choose that specific independent contractor based on their experience, skill, etc, and the occupier oversaw the work to ensure it was done correctly.

In Haseldine v Daw (1941) (CoA) the claimant was injured when the lift he was in plummeted to the ground. The landlord was not liable because it had been reasonable to hire a competent firm of lift engineers, who had checked the lift a week before the accident, as it was a technical job and he didn’t have the specialist knowledge.

In contrast, in Woodward v Mayor of Hastings (1954) (CoA) an icy step that had not been dealt with effectively caused the claimant to slip and injure themselves. This was not a technical issue and the occupier should have been able to check the work of the cleaners and identify this risk.

WARNING NOTICES – OLA 1957

When assessing whether an occupier has discharged their duty of care the court can take into consideration all of the circumstances of the case including any warnings given by the occupiers. A warning will only discharge the occupier’s duty if it is sufficient to make the visitor reasonably safe in all the circumstances s.2(4)(a). This is a higher standard than merely warning of the danger.

In Roles v Nathan (1963) (CoA) the caretaker of the building had given sufficient verbal warnings to the two chimney sweeps about the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning to have discharged the occupier’s duty.

An example given by Lord Denning in Roles v Nathan (1963) (CoA) illustrates the role that warnings play in discharging an occupier’s duty. Denning asks the reader to imagine a property to which access in and out is only possible over a completely rotten and dangerous bridge. A simple warning sign to say that the bridge is dangerous would not be sufficient because the warning does not make the visitor reasonably safe in all of the circumstances. The visitor still has to use the bridge to cross the river. However, if there was another bridge nearby which the visitor is signposted to then a warning sign on the old bridge would be sufficient because that enables the visitor to be reasonably safe in all of the circumstances.

WARNING NOTICES – OLA 1984

Under the OLA 1984 the occupier only has a duty to take reasonable steps to warn any trespasser of the danger, it is not as high as the standard under the OLA 1957 that warnings must keep the visitor reasonably safe in all of the circumstances. Therefore a duty to warn of dangers will be easier to discharge for trespassers than for visitors.

OBVIOUS DANGER

If a danger is really obvious then there may be no duty to warn a visitor (Staples v West Dorset District Council (1995) (CoA)).

The claimant slipped on a sea wall known as the Cobb in Lyme Regis. The wall was covered in seaweed and algae and it was obvious that it was slippery and dangerous. The council did not owe a duty to warn of this risk because it was so obvious.

This was also discussed in obiter dicta in Tomlinson v Congleton (2003) (HoL), the inherent risk in diving into a lake was so obvious that the council may have had no duty to warn against it.

EXCLUSION OF LIABILITY

A warning notice may also be an attempt to exclude liability, e.g. ‘Do not enter. The occupier will not be liable for any injury’. Any exclusion notice such as this will be governed by the Unfair Contract Terms Act (1977).

DEFENCES

VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA

The common duty of care does not impose on an occupier any obligation to a visitor in respect of risks willingly accepted as his by the visitor (the question whether a risk was so accepted to be decided on the same principles as in other cases in which one person owes a duty of care to another).

An occupier can try to argue the defence of volenti non fit injuria, that the visitor consented to the risk. This is legislated for in the OLA 1957 s.2(5) which states that a duty of care does not include risks willingly accepted as his by the visitor. All of the normal considerations apply (see Defences); the visitor must have voluntarily agreed to the specific risk.

In White v Blackmore (1972) a man died when a motor-racing car wheel crashed into the barrier that he was standing behind and threw him into the air. Signs at the site and in the programme had warned of the danger to spectators. However, the court held that as the victim was standing some way from the barrier he could not have been fully aware of the specific risk posed by the inadequate barrier and therefore could not have agreed to it.

However, this claim did not succeed as the defendant had taken reasonable steps to tell all visitors that they had excluded their liability. Therefore they did not owe the victim a duty of care. Note that this was a case before the enactment of the UCTA 1977.

TRESPASSERS

Trespassers are also subject to the defence of volenti non fit injuria. As can be seen from the case of Tomlinson v Congleton (2003) (HoL) (above) the courts are prepared to deny a claimant damages if they believe that their injury was caused by their own choice to take the risk. Although in that case the defendant did not owe the claimant a duty of care.

CONTRIBUTORY NEGLIGENCE

The normal rules for contributory negligence apply as set out in the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945. This is stated in OLA 1957 s.2(3). (See Defences)

A trespasser can also be subject to contributory negligence. In the case of Revill v Newbury (1996) (CoA) Newbury, worried about theft from his allotment shed, decided to sleep in his shed with a loaded shot gun. When Revill tried to burgle the shed Newbury fired the gun through a hole in the door intending to scare him away but Revill was hit and injured. The court held that Newbury did owe Revill a duty of care as set out in OLA 1984 and he had breached that by not taking reasonable care for his safety. However, the court did reduce Revill’s damages by two-thirds to reflect his contributory negligence.