JUMP TO: COMMON LAW | CONSUMER | MANUFACTURER | BREACH | CAUSATION | DAMAGES | DEFENCES | CPA 1987 | REVISE | TEST

PRODUCT LIABILITY

A claimant can bring a claim for a defective product under common law or statute (Consumer Protection Act 1987).

COMMON LAW

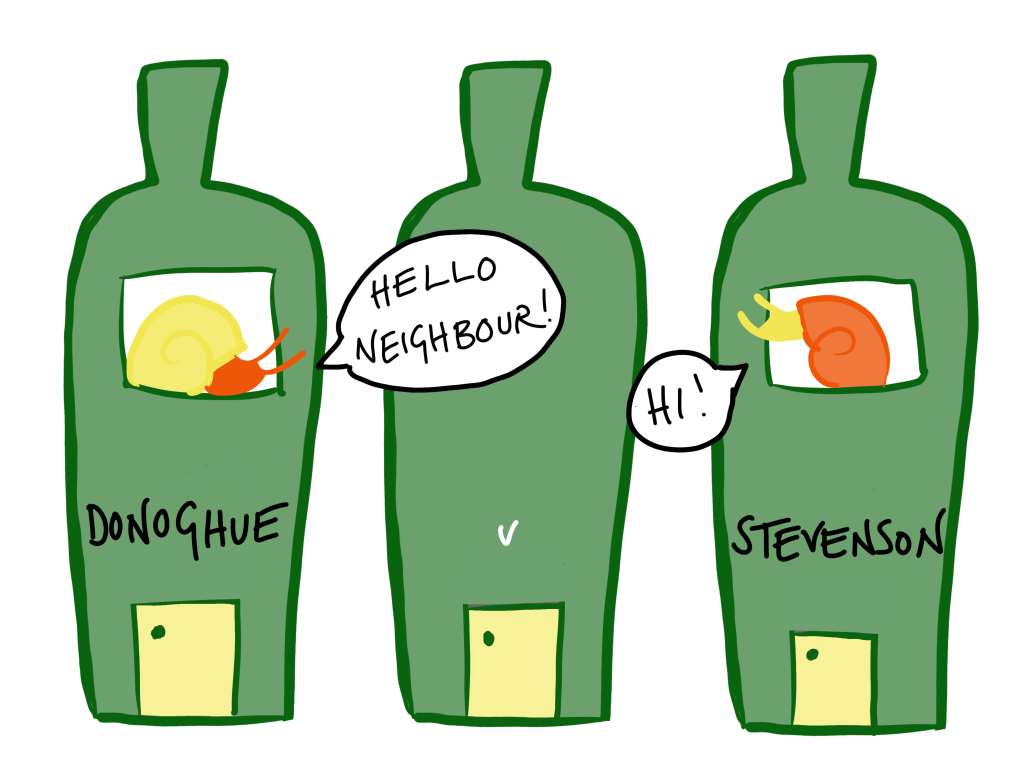

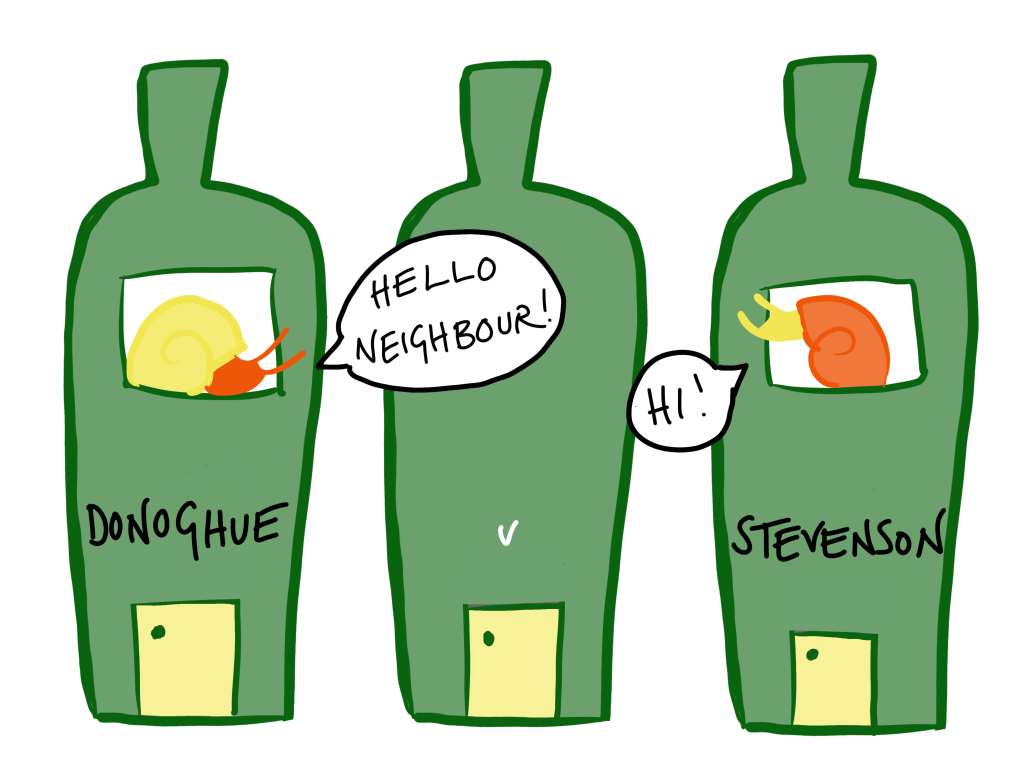

A common law duty between manufacturers and consumers was established in the case of Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) (HoL). (See our blog post for the background details to this seminal case).

Mrs Donoghue was made ill after drinking a bottle of ginger beer containing a decomposing snail. She was not able to make a claim in contract because it had been her friend who had purchased the drink. At the time the law was such that the producer of the ginger beer did not owe her any duty of care. However, this landmark case changed that. The change in the law, as stated by Lord Atkin, was that, ‘You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.’

In reference to the duty of care between manufacturers and consumers he went on to say… ‘a manufacturer of products, which he sells in such a form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take that reasonable care.’

WHO IS THE ULTIMATE CONSUMER?

The duty of care is owed to the ‘ultimate consumer’, this is anyone that could reasonably be foreseen to be affected by the defective product. So in Donoghue it was the consumer of the drink but it could be anyone who has come into contact with the product.

In Stennett v Hancock & Peters (1939) the claimant was hit by part of a lorry’s wheel. He was considered a ‘consumer’ for the purposes of finding a duty of care. The ‘product’ was the vehicle which had been repaired negligently by the defendant mechanics. The judge stated that they should have foreseen that not repairing the vehicle properly could injure someone.

WHO IS THE MANUFACTURER?

Originally most product liability cases were brought against the manufacturer, take Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) (HoL) for example. However, nowadays the ‘manufacturer’ of the product can be anyone who has been involved with the product at any stage, including repairers, suppliers and distributers who should have inspected the product and discovered the defect. A defect can be in any part of the product including the packaging.

In Haseldine v Daw (1941) (CoA) the claimant was injured when the lift he was in plummeted to the ground. He brought a case against both the landlord and the lift engineers. The lift engineers, who had inspected the lift a week before the accident and stated it was in good working order, were held to be the ‘manufacturers’ and liable for the defect. The landlord was not as it had been reasonable to entrust this specialised work to a competent firm of lift engineers.

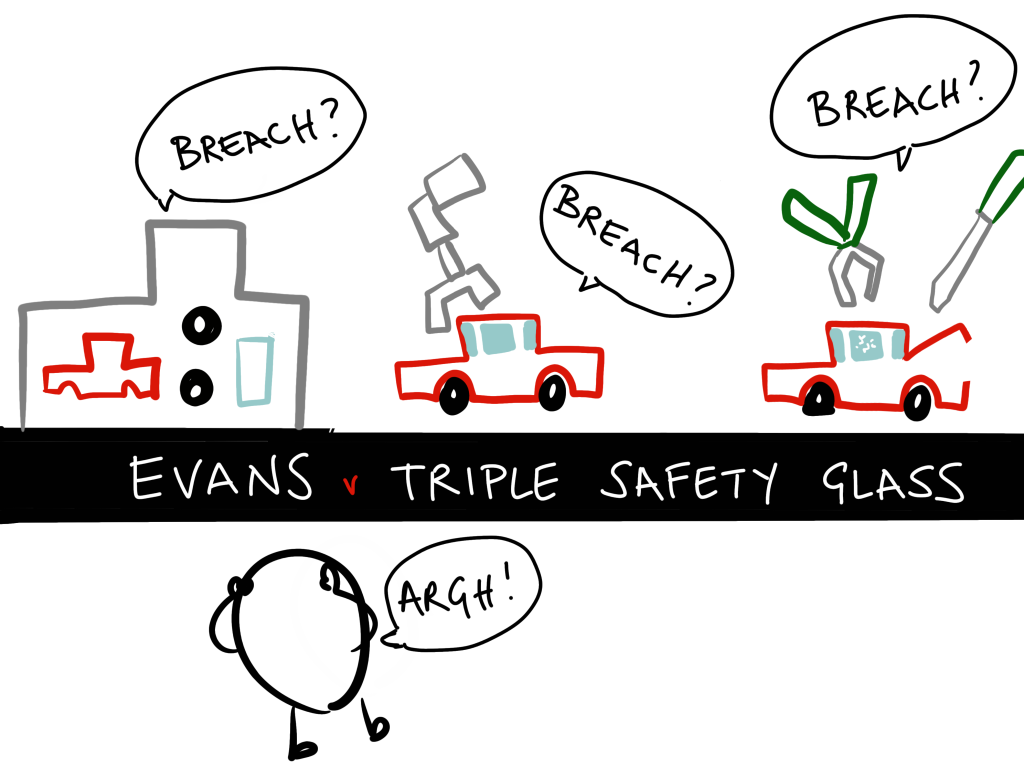

BREACH

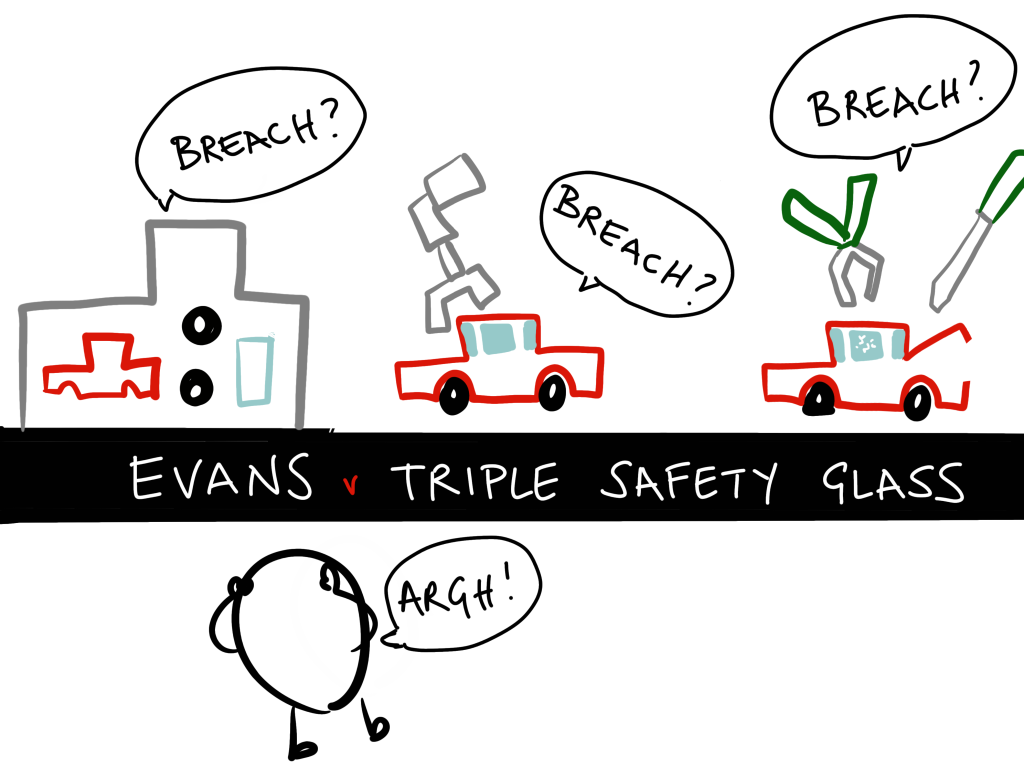

The ordinary rules of standard and breach apply to product liability. However, in cases involving products comprised of different components made by different manufacturers it can be difficult to prove where the breach occurred and who was therefore responsible.

In Evans v Triplex Safety Glass (1936) the claimant had bought a Vauxhall car with a Triplex toughened windscreen. When it shattered and injured his passengers the claimant sued the manufacturer. However, he was unable to prove breach because he could not show that it was definitely the defendant that had acted negligently. The court felt it was more likely the fault of Vauxhall who would have fitted the glass and could have identified any defects inherent in the windscreen when assembling the car.

CAUSATION

In addition to the ordinary rules of causation the fact that the product has, or should have, been inspected by any party may break the chain of causation. This was specified in Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) (HoL).

The claimant’s own failure to inspect the product can break the chain of causation, although the defect would have to be overt.

In Grant v Australian Knitting Mills (1936) (PC) the claimant contracted dermatitis from a pair of underpants that still contained chemicals from the washing of the wool. The defendant argued that the claimant should have inspected the product and washed it before use. This was rejected by the court; excessive chemicals on the product were a latent defect which the claimant could not have discovered through inspection and the claimant had not been told to wash the product before use, so the actions of the claimant did not break the chain of causation and the manufacturer was still liable.

Whether a party should have checked the product will be based on what is reasonable in the circumstances of the case. This will depend on such factors as whether there was a warning to inspect on the packaging that was ignored by the claimant. In Holmes v Ashford (1950) (CoA) a hairdresser failed to test a hair dye as instructed before using it on a client. The hairdresser and not the manufacturer was liable.

If the claimant knew of the defect and appreciated the danger but used the product anyway then their own actions could break the chain of causation. In Farr v Butters Bros (1932) an experienced foreman constructed a crane out of parts sent by the defendant manufacturer. He noticed the defects but used the product anyway and died. The manufacturer was not liable as the foreman’s actions broke the chain of causation.

Also compare Andrew v Hopkinson (1957) and Hurley v Dyke (1979) (CoA). In the former a second hand car dealer was liable for the serious defect found in a car that he sold. He had the opportunity to inspect and the defect would have been obvious to any competent mechanic. In the latter a second hand car was sold ‘as seen and with all faults’, this absolved the seller from any liability.

REASONABLE PROBABILITY

The difficulty in ascertaining where a defect arose means that the courts often have to work out what was most likely. In Grant v Australian Knitting Mills (1936) (PC), although it could not be proved exactly where the chemicals came from the court was willing to accept that it was very unlikely that the chemicals originated from anyone but the manufacturer. The court was unwilling to accept the defendant’s argument that the product could have been tampered with.

In Evans v Triplex Safety Glass (1936) (above), the ‘reasonable probability’ that the glass had been interfered with, i.e. fitted incorrectly, was enough to break the chain between the manufacturer and claimant.

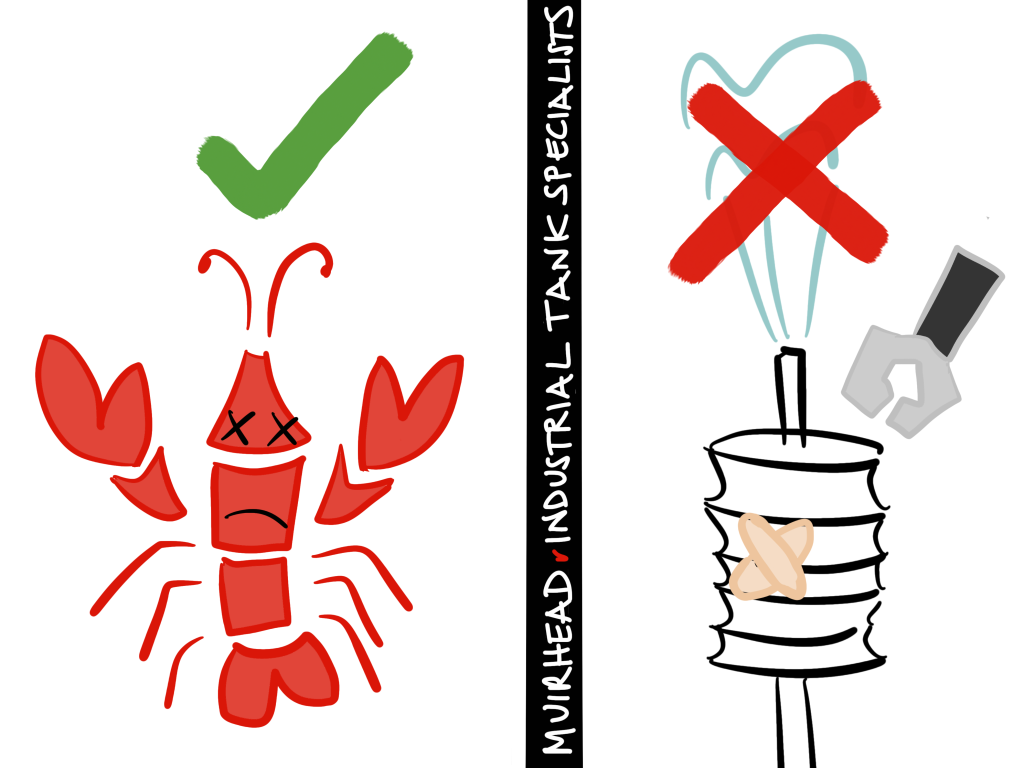

DAMAGES

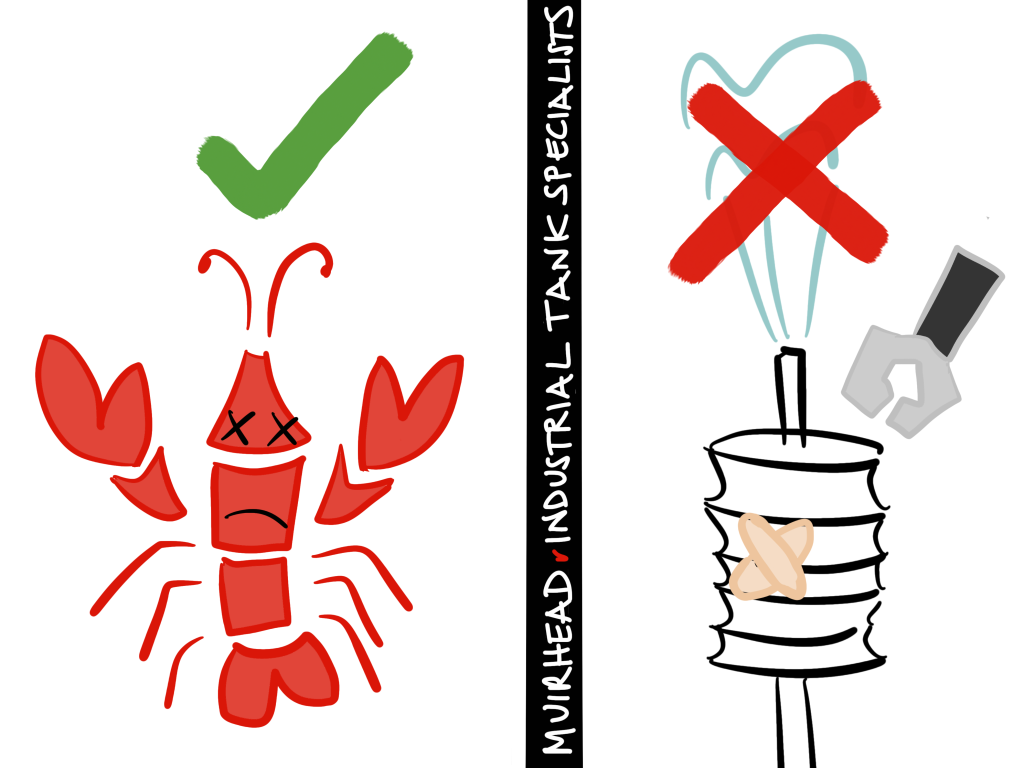

A claimant can recover for personal or property damage caused by a defective product but not for the costs of repair to the product as this is categorised as pure economic loss.

For example, in Muirhead v Industrial Tank Specialists (1986) (CoA) faulty pumps were supplied to the claimant for use in lobster tanks. When the lobsters died the claimant sued the maker of the pumps. A claim was allowed for the price of the dead lobsters (property damage) but not for the cost of the defective pumps (pure economic loss).

DEFENCES

A defendant will not be liable if the product was not defective at the time that they supplied it to the claimant but the defect was acquired after it left the control of the defendant.

The defendant will also not be liable if the claimant used the product in an unforeseeable way or for an unforeseeable purpose.

CONSUMER PROTECTION ACT 1987

The CPA imposes a strict liability on manufacturers. Unlike common law negligence the claimant need not show that the defendant was at fault or negligent they just need to prove that the product was defective and it caused damage.

The Act gives a wide definition to both claimant, s.2(1), and defendant, (s.2(2)(a)-(c)). In this there is not much difference between the Act and common law. Although the Act does state that multiple defendants (i.e. manufacturers of component parts), if all found liable, will be jointly and severally liable.

What constitutes a product or goods is outlined in s.2(1) and s.45 and the definition is very broad, including, for example, blood (A v National Blood Authority (2001) (HC)). However, it excludes buildings but includes their component parts such as joists (s.46(3)).

DEFECTIVE PRODUCTS

Much of the case law revolves around what constitutes a ‘defective’ product. This is defined in section 3 as ‘there is a defect in a product…if the safety of the product is not such as persons generally are entitled to expect’.

Several factors to be taken into account are set out;

- the manner in which and purposes for which a product has been marketed,

- the ‘get up’, i.e. packaging, use of marks, e.g. the Kite Mark or instructions or warnings,

- what might be the reasonably expected use for the product,

- the time at which the product was supplied.

DIFFERENT APPROACHES

The approach that the courts take to whether a product is defective or not has changed since the introduction of the Consumer Protection Act 1987. The former leading High Court case of A v National Blood Authority (2001) (HC), which involved patients who had been given contaminated blood, took a fairly restricted view as to which factors were to be considered when asking what ‘persons generally are entitled to expect’ from the safety of a product.

This approach began by identifying the harmful element of the product that caused the injury, then assessing whether that product was standard or non-standard, before deciding if it was defective.

This approach was challenged by another High Court case, Wilkes v Depuy International Ltd (2016) (HC), which involved patients who had been fitted with a specific type of hip replacement. The judge’s approach in this case was to assess whether the product was defective by firstly asking what the ‘entitled expectation’ of persons generally was regarding the safety of the product (rather than starting with what was defective about the product). This is a question of law and not based on an individual’s expectation. Then the court asked whether the product met this expectation, if not then it is defective.

In order to do this they assessed all of the circumstances as presented by the case, including a much wider list than in A v National Blood Authority (2001) (HC). The judge clarified that the avoidability of the defect, the risk-benefit balance and the cost of reducing or avoiding the risk are factors that can be taken into account as there is no requirement of absolute safety in all circumstances. He also stated that adherence, or not, to any appropriate regulations or standards was strong evidence to be considered.

This widening of the factors that could be taken into consideration led to a decision in favour of the manufacturers. The court’s analysis of the risk/benefit balance fell in their favour based on factors such as the similarity between the defendant’s products and others on the market, the product complying with all relevant industry standards and the warnings about the risk being sufficient.

The approach taken in Wilkes v DePuy was followed in both Gee v Depuy International Ltd (The Pinnacle Hip Litigation) (2018) (HC) and Hastings v Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd (2019) (Scottish Court of Sessions), although as yet no case has been heard by a higher court to clarify which approach should be followed.

OTHER EXAMPLES

In Abouzaid v Mothercare (2001) (CoA) the manufacturer was found liable because their product did not include a warning that injury could occur from loss of control of an elastic strap. The court took into consideration that although the risk of injury should have been easy to avoid the defendant had done nothing to reduce the risk. The court held that the product, a baby cover, was an inherently safe product that had caused unexpected injury and was therefore defective.

Compare this to Pollard v Tesco Stores (2006) (CoA); a child had managed to open a child-resistant bottle of dishwasher detergent. The product was not found to be defective because the general expectation was that the bottle should be harder to open than an ordinary bottle. The product complied with this standard even though the child in question had worked out how to open it.

In Sam Bogle v McDonald’s (2002) (HC) the claimant was injured when hot coffee in a McDonald’s cup spilled on her. She argued that the product was defective because the contents were too hot and the lid came off too easily. This was rejected by the court; even though the product came without a warning about hot contents what was generally expected was hot liquid and a lid that came off easily for adding milk, etc, therefore it was the buyer’s responsibility to guard against the risk of scalding not the manufacturer’s.

DAMAGE

Under section 5 of the Act a claimant can claim for death, personal injury and loss of, or damage to, property. However, they cannot claim for the cost of repair or replacement of the defective product nor any other product of which the defective product is a part. This is classified as pure economic loss.

Any property damage must exceed £275 and it cannot be property that was used for business purposes, only private use.

Section 7 states that liability for damage cannot be excluded, so the Unfair Contract Terms Act need never be considered. .

DEFENCES

Section 4 sets out the available defences.

The defect is attributable to compliance with statute (s.4(1)(a)),

The defendant did not supply the goods (s.4(1)(b)),

The supply was otherwise than in the course of business (s.4(1)(c)),

The defect did not exist at the time of supply (s.4(1)(d)),

The development risks defence (s.4(1)(e)), this is similar to the concept in Roe v Ministry of Health (1954) (CoA) in that if the risk is not known to science at the time of manufacture then the manufacturer cannot have been expected to know about it and avoid it. But note that in A v National Blood Authority (2001) (HC), although the risk of infected blood was known about there was no technology that could successfully screen for it. However, this was not sufficient to act as a defence and the defendants were found liable.

Manufacturers of component parts will not be liable if it can be shown that the defect was attributable to another component of the product (s.4(1)(f)).