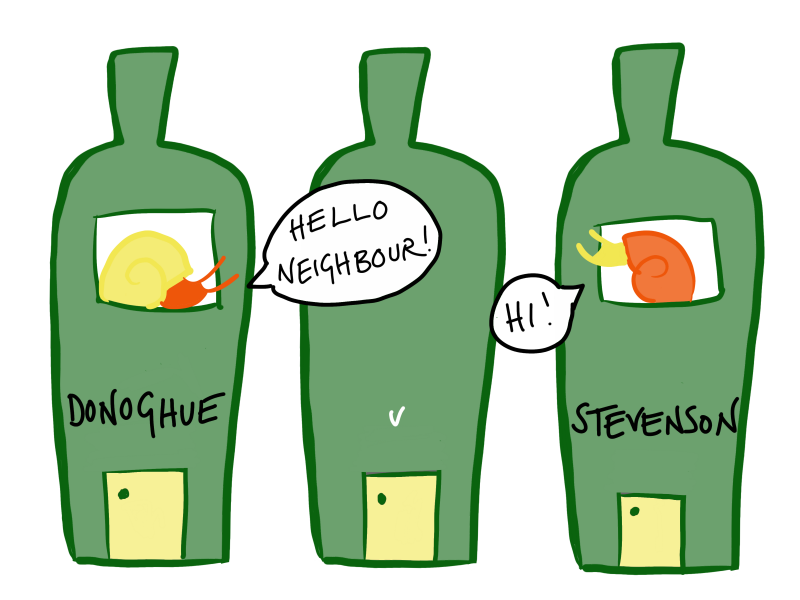

Case Summary…the background to Donoghue v Stevenson (1932)

What are the facts of Donoghue v Stevenson?

Mrs May Donoghue, like Mrs Carlill, is a woman whose legal case advanced the law into a new area. Her case brought in the concept of negligence law – that parties such as manufacturers could owe a duty of care to those who would consume their products even if they had not been the party that bought the product.

See General Duty of Care and Product Liability pages for examples of how Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) is applied in law.

Who was Mrs Donoghue?

May Donoghue, born in 1898, was 30 years old when her legal journey began, after her famous encounter with a dead snail. Married at 17 she fell pregnant following an affair with an older man. The marriage was unhappy and the family did not thrive, 3 more children were all born prematurely and died of malnutrition. When she become one of the most famous claimant’s in English legal history she had separated from her husband and was living with her brother in a tenement building in central Glasgow.

What happened to Mrs Donoghue?

On 26th August 1928 she left her home to meet a friend in Paisley, just outside Glasgow. They met at the Wellmeadow Café where she ordered a Scotsman’s Ice Cream Float, a mixture of ginger beer and ice cream. When Mrs Donoghue topped up her float with the rest of the ginger beer from the Stevenson’s bottle the remains of what seemed to be a dead snail ended up in her glass. She suffered shock and gastroenteritis, later being treated at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

Donoghue v Steveson – the legal background

The presence of decomposing animals in Scottish ginger beer bottles in the late 1920s seems to have been more common than one would have thought. The solicitor who represented Mrs Donoghue, Walter Leechman, had already been involved in a couple of other cases involving dead mice in ginger beer bottles. However, these conjoined cases (known as Mullens v Barr (1929)) had been dismissed by the Scottish Courts which stated that the defendants did not owe the claimants a duty of care and there was no claim in contract as the claimants had not been the ones to buy the product.

Mr Leechman was clearly committed to the cause and, not to be discouraged, he offered to represent Mrs Donoghue for free and brought her case only twenty days after the decision had been handed down against the claimants in Mullens v Barr. Although Mrs Donoghue was unsuccessful in the Scottish Court of Appeal it was decided to take the case to London and the House of Lords. In order to not have to put up security for her legal costs she had to officially register as a pauper which entailed a signed affidavit in which she swore ‘I am very poor. I am not worth five pounds in all the world’, this was sent with a petition to a committee of the House of Lords (which included the Duke of Wellington) to be confirmed.

When Mrs Donoghue’s case made it to the House of Lords she was represented by a Scottish barrister, Mr Milligan, who was an Olympic runner and had participated in the race round the Cambridge quad made famous by the film ‘Chariots of Fire’.

Donoghue v Stevenson – the verdict

The House of Lords in their decision split 3:2 in Mrs Donoghue’s favour. The three assenting judges were Lord Atkin, Lord Macmillan and Lord Thankerton. But why did they find in her favour? Lord Atkin was clearly interested in the interplay between Christian morality and tort law and whether the latter should reflect the former more closely. His ‘Neighbour Principle’ was a reflection of this. Mrs Donoghue’s case also turned out to be well timed as he had made a speech on the subject not six weeks before the case. Unlike the dissenting judges Lord MacMillan agreed with Lord Atkin and was happy to extend the bounds of negligence law famously saying, ‘the categories of negligence are never closed’ and Lord Thankerton, well, he was known for not only knitting during trials but also often falling asleep.

Once the House of Lords had decided that legally Mr Stevenson, as the manufacturer, could owe Mrs Donoghue, as the ultimate consumer, a duty of care the case went back to the court in Scotland to be tried on the facts. However, before it could be heard Mr Stevenson died and Mrs Donoghue did not transfer the claim to his estate. Because there was no trial on the facts controversy arose as to whether there had ever been a snail in the bottle. This, however, seems to have been a rumour started by the barrister who had unsuccessfully represented Mr Stevenson in the House of Lords. Mrs Donoghue was given a settlement nonetheless although the amount is disputed. In all likelihood £200, the equivalent of about £10,000 today.

Today Mrs Donoghue’s influence on modern tort law is commemorated in Paisley by a statue of her and a wooden bench donated by the Canadian Bar Association. She died in 1958 from a heart attack.

#carlilandcarbolic #lawstudyresources #donoghuevstevenson #dutyofcare #tortlaw