This page covers how the courts establish a duty of care between the claimant and the defendant in a case of negligence. Specifically it focuses on the important case of Robinson v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police when establishing a duty of care, whether a defendant can owe a duty of care for an omission, or for the acts of a third party, and do rescuers owe a duty to people they rescue?

Revise this topic | Test this topic

GENERAL DUTY OF CARE

In order to be liable for an act of negligence the defendant must have owed the claimant a Duty of Care at the time of performing the act.

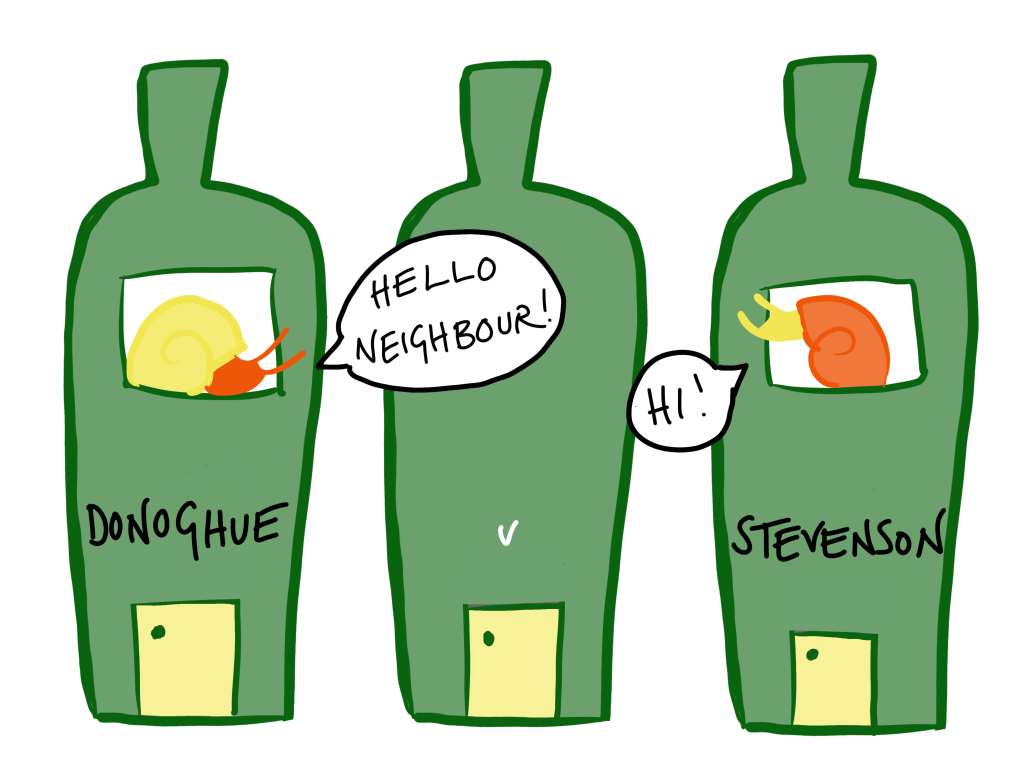

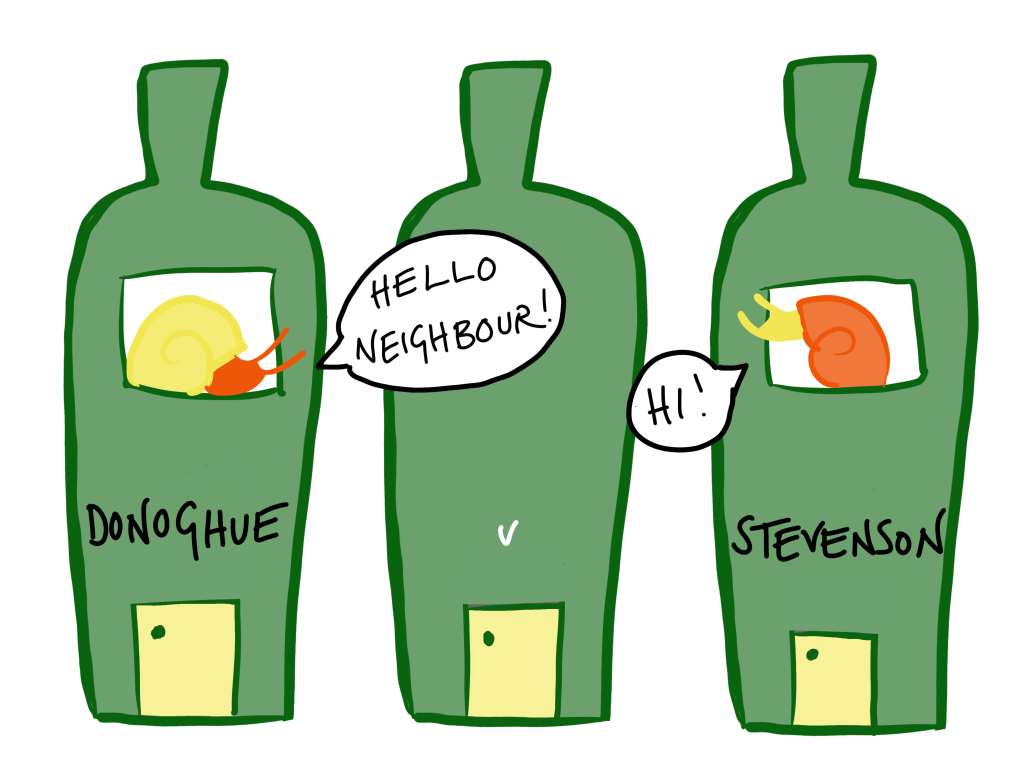

This was established in the case of Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) (HoL) in which Mrs Donoghue was made ill after drinking a bottle of ginger beer containing a decomposing snail. She was not able to bring a claim in contract because she was not a party to the contract, it was her friend who had purchased the drink. At the time, in tort law, the producer of the ginger beer did not owe her any duty of care. However, this landmark case changed that and paved the way for modern negligence law. The change in the law, as stated by Lord Atkin, was that, ‘You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.’

Lord Atkin defined a neighbour as, ‘persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.’ (See our blog post for the details behind this seminal case).

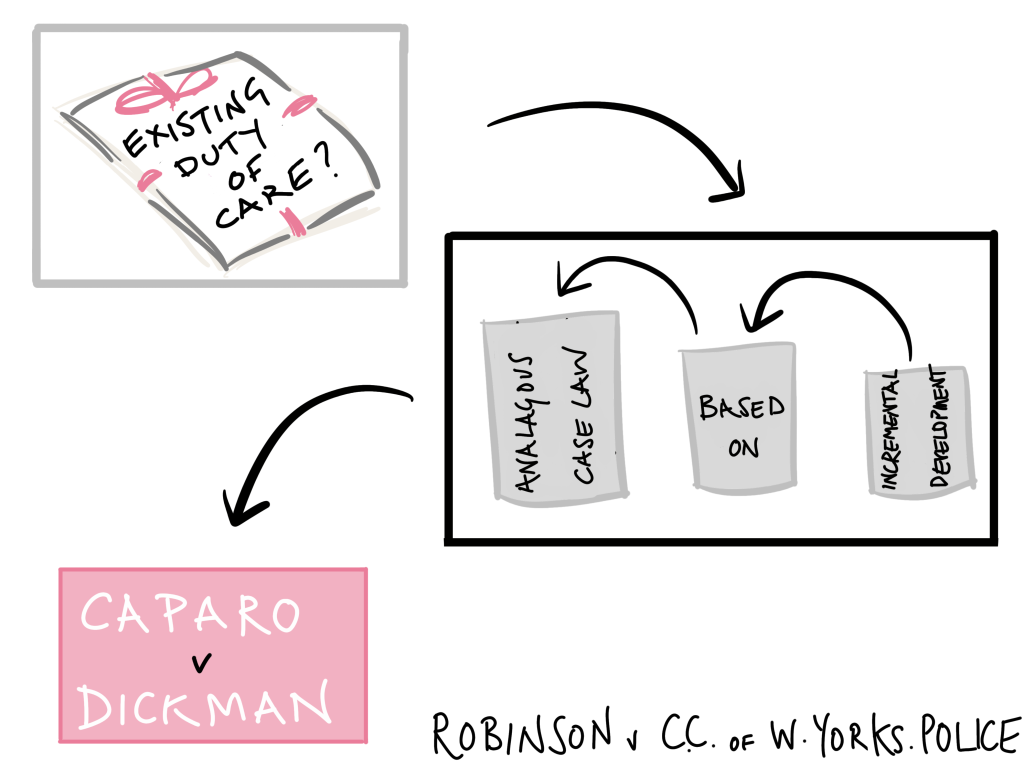

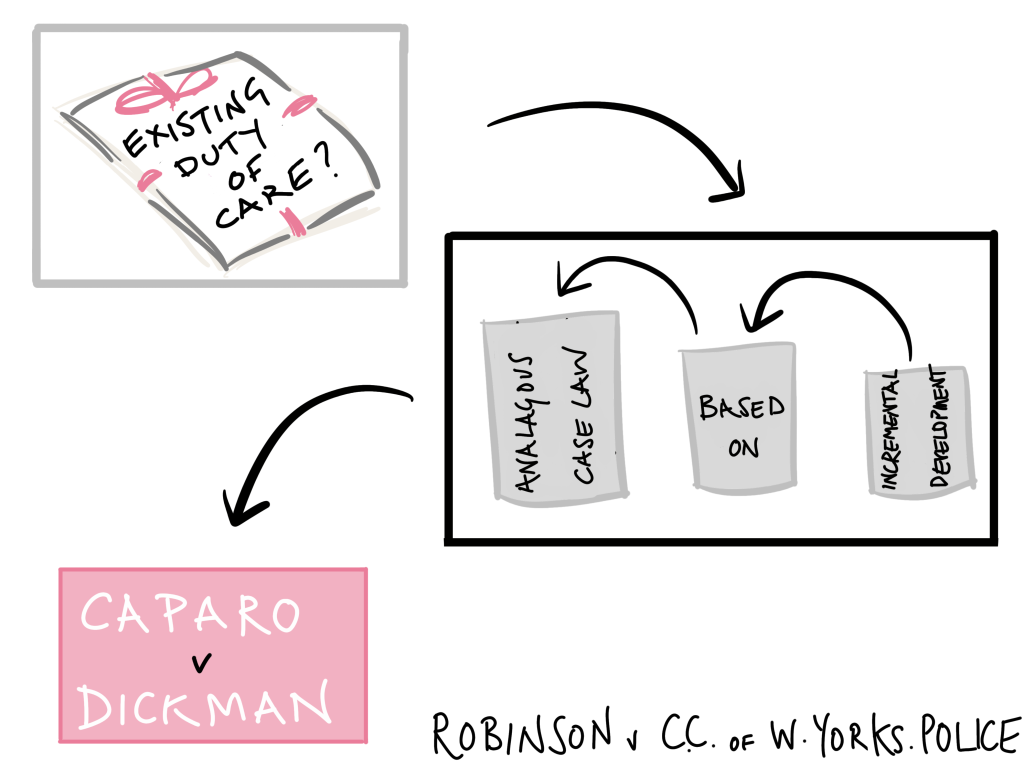

Several different approaches have been formulated by the courts since then for formulating when a duty of care is owed including the three stage test in Caparo v Dickman (1990) (HoL) (as discussed below) and most recently the approach taken in Robinson v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police (2018) (SC).

An elderly woman was knocked over by two police officers as they attempted to arrest a drug dealer. They were found liable for her injuries as it was reasonably foreseeable that the police officers’ actions would cause the claimant harm, based on the Donoghue v Stevenson neighbour principle.

The court set out the approach that the courts should take when addressing questions of whether a duty of care exists.

1. Follow precedent if possible,

2. If not, develop case law incrementally from analogous cases,

3. If no analogous cases exist and the situation is completely novel only then revert to the Caparo v Dickman test. . |

PRECEDENT

Firstly the court should always look to follow precedent if one exists. A good example of this comes from Poole Borough Council v GN (2019) (SC) the first Supreme Court case to follow Robinson and implement the new approach.

GN were two children who had been housed, with their mother, in a council house next door to people known to engage in anti-social behaviour. The family was harassed by their neighbours leading to the children suffering physical and psychological harm. However, the court held that there was no duty of care owed because the council had never assumed responsibility for the children. Their role in monitoring the situation and investigating the risk posed by the neighbours was not a specific service on which they could reasonably have relied, nor had the family entrusted their safety to the council or been taken into care.

The court did not use the Caparo v Dickman test to establish whether there was a duty of care but relied upon existing case law involving when a council owed a duty of care to children such as X (minors) v Bedfordshire (1995) (HoL) or X & Y v Hounslow London Borough Council (2009) (CoA) (see Public Body Duty of Care section).

ANALOGOUS CASES

If no direct precedent exists then the court should seek analogous cases to inform their decision but always aiming to maintain the coherence of the law and avoid inappropriate distinctions. If there is scope to extend the law based on existing precedent the court can at this stage consider whether any extension would be just and reasonable.

A good example of this is Darnley v Croydon Health Services NHS Trust (2018) (SC) (also decided post-Robinson). The claimant, having been given incorrect information by an A&E receptionist about waiting times left A&E without seeing any member of medical staff about his head injury. When his condition worsened later that day he was taken to hospital but suffered permanent brain damage.

Although no exact precedent existed for injury caused by the negligence of a hospital receptionist, or non-medical staff, the court held that this case fell within the same established category of duty as Barnett v Chelsea and Kensington (1969) (HC), a duty to not cause physical injury to the patient. Once Darnley had arrived at hospital and been seen by a member of staff then the hospital owed him a duty of care. The fact that it was a non-medical member of staff who breached that duty did not mean that the court had to use Caparo to establish a new category of duty of care.

The court also considered analogous cases such as Kent v Griffiths (2001) (CoA), in which a duty of care was owed by an emergency services telephone operator (a non-medical member of staff). Based on this the court held that there was no distinction between medical and non-medical staff, they all owed a duty of care to patients to not provide misleading information.

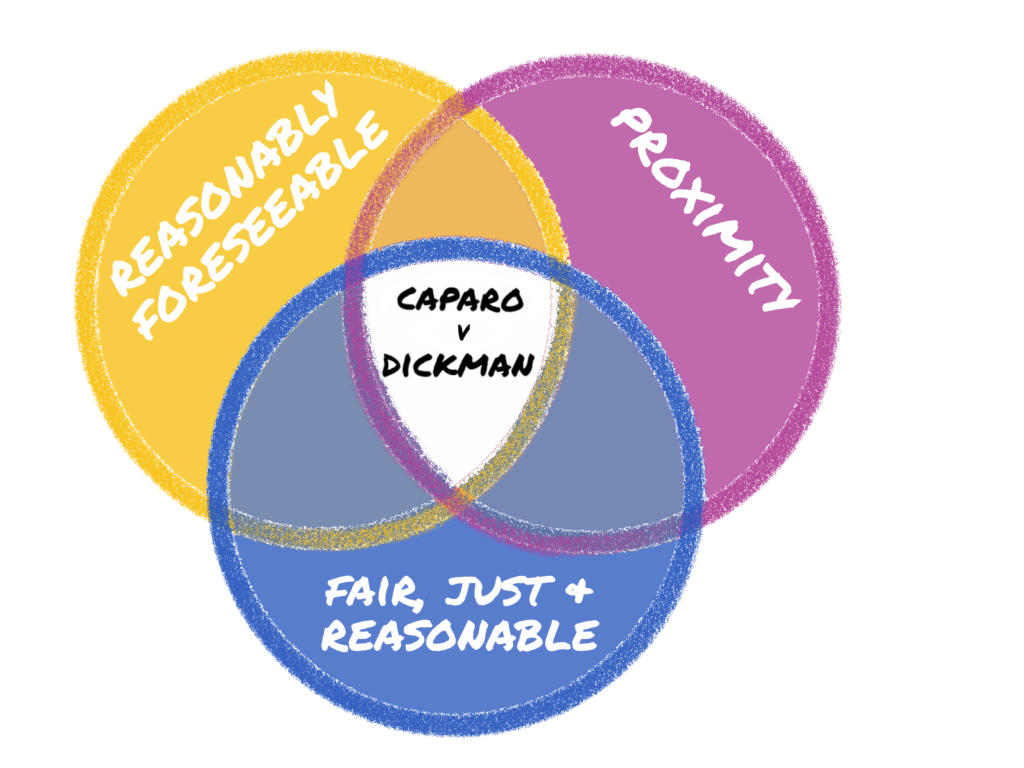

CAPARO v DICKMAN TEST

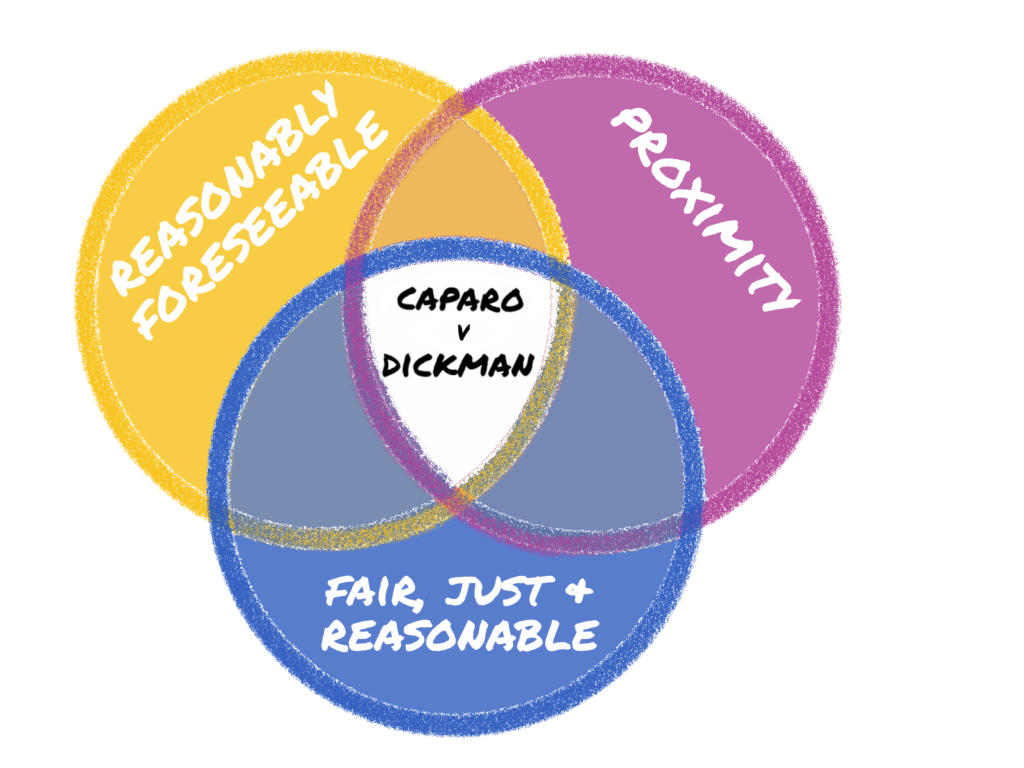

The court should seek to develop the law incrementally based on existing case law rather than starting afresh in each new case with the test from Caparo v Dickman (1990) (HoL). Only if the court is faced with a case involving a relationship between the parties or set of facts that is completely novel should they use this test.

The test comes from Caparo v Dickman (1990) (HoL), a case concerning a negligent misstatement. The court must ask the following questions to establish whether there was, or should be, a duty of care between the claimant and the defendant.

1. Was the damage to the claimant a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s actions?

2. Was there a relationship of sufficient proximity between the claimant and the defendant?

3. Is it ‘fair, just and reasonable’ for the law to impose a duty of care in the situation? |

FORESEEABLE

Damage to the claimant must be a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s negligent action. The claimant need only be part of a class of people to whom harm was reasonably foreseeable. For example, in Donoghue v Stevenson (1932) (HoL) the fact that any consumer of the ginger beer would have suffered damage was sufficient, it did not have to be foreseeable that Mrs Donoghue specifically would suffer damage.

SUFFICIENT PROXIMITY

The claimant and defendant must have a relationship of sufficient proximity. A good example of this is Caparo v Dickman (1990) (HoL) itself. Dickman had audited the accounts of a company. Caparo had relied upon those accounts when deciding whether or not to invest in the company. The audit showed that the company was prospering but after buying shares Caparo discovered that the company was basically worthless. They sued Dickman for negligent misstatement. However, the court found that the audit was a statement designed for shareholders and not for potential investors therefore there was no relationship of sufficient proximity between the parties and Caparo was not owed a duty of care by Dickman.

FAIR, JUST & REASONABLE

This is the part of the test that allows the courts to assess whether there are any public policy or reasons of justice, why a duty of care should or should not be found. For example, the courts may decide that if they find a duty of care then this will open the floodgates for many more cases of a similar nature. Or the courts might think that a particular scenario should be dealt with by parliament and not the courts.

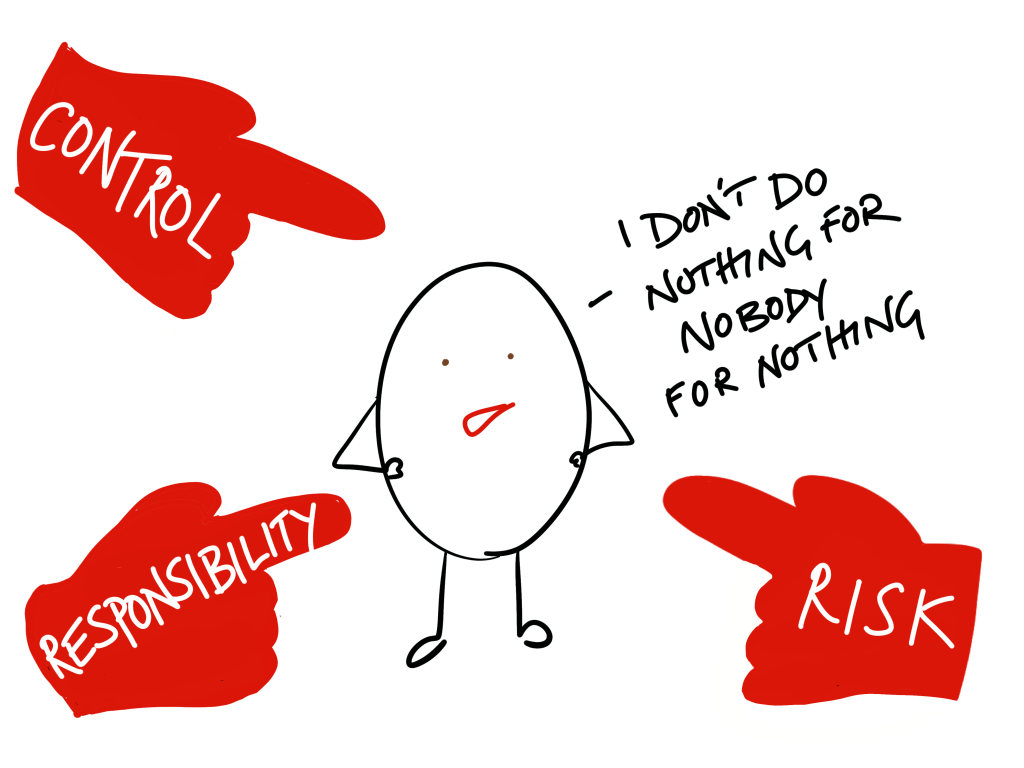

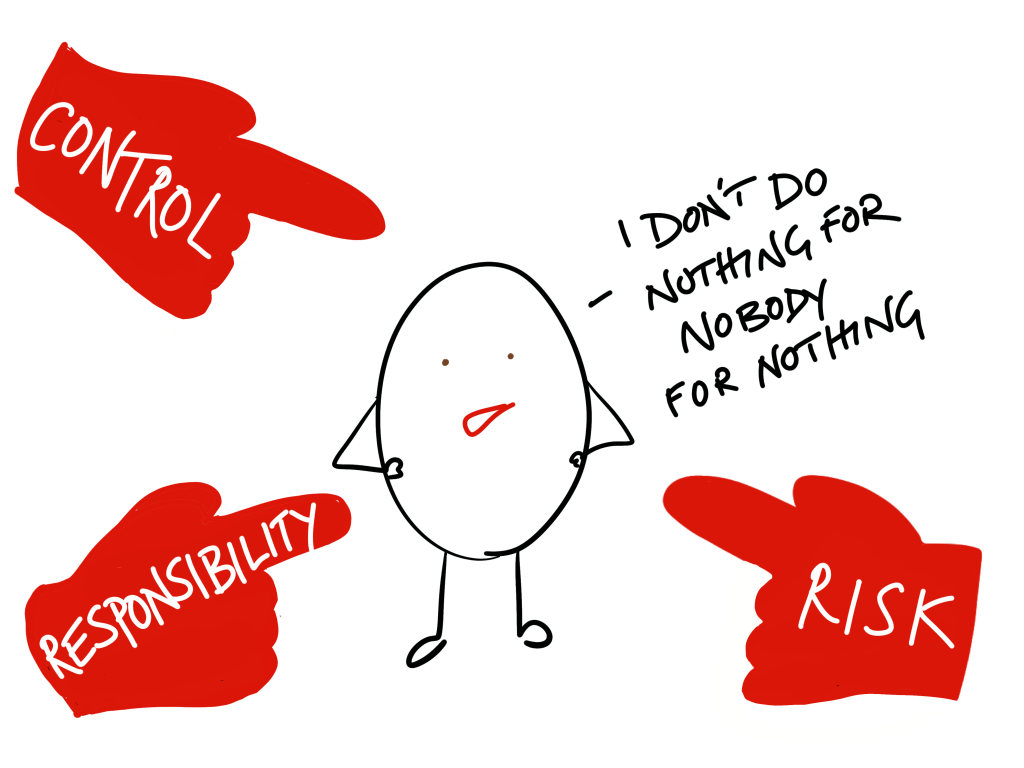

OMISSIONS

In general an omission will not give rise to a duty of care, the defendant will usually have to have acted in some way that caused harm. The classic example is if someone sees a child drowning there is no duty on the observer to try to rescue them and no liability for doing nothing. There is no liability for being a bad Samaritan.

However, there are exceptions to this rule…

CONTROL

If the defendant has a high degree of control over the claimant then a duty of care will arise not only to not inflict harm but also to stop the claimant being harmed by another or themselves (Reeves v Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis (1999) (HoL)).

When Martin Lynch committed suicide in police custody the police argued there was no duty of care owed. They argued that although a duty of care had been found in a similar case (Kirkham v Chief Constable of Greater Manchester (1990)) that had involved a mentally ill prisoner and Martin Lynch had not been mentally unwell. However, the court disagreed. The police had a duty for all prisoners because of the high level of control exercised over them and the high incident of suicide in prisoners, even those without a recognised mental illness. It was only by their negligence that Lynch had had the opportunity to commit suicide. However, the compensation was reduced by half because Lynch had died due to his own actions.

This was clarified in Orange v Chief Constable of Yorkshire Police (2001) (CoA) as only a duty to assess each prisoner’s risk of suicide. If the risk was low there was no duty to prevent suicide.

ASSUMPTION OF RESPONSIBILITY

A defendant can have assumed responsibility for the claimant (Costello v Chief Constable of Northumbria Police (1999) (CoA)).

A police officer was attacked by a prisoner. Despite calling for help Costello’s colleagues did not come to her aid. The defendant argued that they could not be liable for an omission. However, the court held that a policeman’s employment contract gave rise to an assumption of responsibility for the safety of fellow officers, there was a positive duty to ‘watch each other’s backs’ and therefore they had owed her a duty of care.

A duty of care for an omission can also be assumed based on the preceding actions of the defendants. As mentioned above a bystander has no duty to help someone in need but if they do try to help they may have assumed some level of responsibility. In Barrett v Ministry of Defence (1995) a very drunk naval pilot died when he choked on his own vomit. The officer in charge was held to have assumed responsibility for him when he ordered someone to put him to bed and breached that duty by not having someone watch over him through the night.

In Home Office v Dorset Yacht (1970) officers running a borstal on Brownsea Island allowed a group of young offenders to escape, an omission. However, as the officers had assumed responsibility for the young offenders they owed a duty of care to those affected by their actions. This is discussed below under Actions of a Third Party.

Note that no case has arisen when a duty of care has been found based on assumption of responsibility between strangers, in both of the preceding examples the parties already had a relationship of sufficient proximity.

DEFENDANT CREATED THE DANGER

If a defendant has created a danger, even by mistake, then there may be a duty upon them to act to avert the danger (Capital and Counties v Hampshire County Council (1997) (CoA)).

The fire brigade does not owe a general duty of care to the public but they do if they create the danger or make it worse by their actions. The Hampshire fire brigade had turned off the sprinkler system in the claimant’s property, thereby allowing the fire to spread more easily.

In Goldman v Hargrave (1967) (PC) a tree had been set on fire by lightening. The owner of the land had had the tree cut down but had decided to let it burn rather than extinguish the fire. The fire spread to a neighbour’s property causing significant damage. The court held that although the defendant had not caused the danger he had adopted the risk by felling the tree but not putting the fire out and was liable for the damage caused to the neighbour’s property.

STATUTE

Some statutes impose a positive duty to act and failure to do so could be the basis for a claim in negligence.

|

CONTRACT

If a contract includes in it a duty to act then again a failure to do so may lead to a claim in negligence but it would depend on the wording of the contract.

|

LIABILITY FOR ACTS OF A THIRD PARTY

In general a defendant will not be liable for the acts of a third party. However, there are several exceptions; a relationship of proximity between the claimant and defendant, a relationship of control between the defendant and the third party, the defendant creates the source of danger that is ignited by the third party and a known danger of a third party is ignored by the defendant.

RELATIONSHIPS OF PROXIMITY BETWEEN CLAIMANT AND DEFENDANT

If the claimant can prove that there was a sufficiently close relationship between themselves and defendant and the defendant assumed responsibility for the safety of the claimant then the defendant’s duty of care may include the actions of third parties (Stansbie v Troman (1948) (CoA)).

A contractual relationship between the claimant and defendant created a relationship of sufficient proximity to create a duty of care that included liability for the actions of third parties. Troman had been hired by Stansbie to decorate her house. She had specifically instructed him to lock the door after he left. He failed to do so and the house was robbed. Troman was liable for the actions of the third party, the burglar.

This can also be viewed as an issue of causation – did the third party break the chain of causation between the defendant and the claimant? See the page on Causation.

SPECIFIC ASSUMPTION OF RESPONSIBILITY

In order for a duty to exist the defendant must have assumed responsibility for that claimant specifically (Palmer v Tees Health Authority (1999) (CoA)).

A psychiatric patient was released from hospital. He missed an outpatient appointment and went on to kill a child. The mother of the child tried to sue the health authority as responsible for the actions of the patient, the third party. However, the courts did not find a relationship of sufficient proximity between the claimant and defendant. The child was not sufficiently identifiable as a potential victim (even though she lived on the same street as her murderer and he had threatened to kill a child whilst in hospital) for the health authority to have specifically assumed responsibility for her against the actions of the third party.

The need for a specific assumption of responsibility by the defendant for the claimant was emphasised in Mitchell v Glasgow City Council (2009) (HoL). Mitchell was killed by his neighbour, Drummond, both tenants of the Council. The Council knew about threats to Mitchell’s life made by Drummond and other anti-social behaviour. Immediately after a meeting, in which the Council reprimanded Drummond and threatened him with eviction if he did not change his behaviour, Drummond killed Mitchell. The court held that unless the defendant has ‘by his words or conduct assumed responsibility for the safety of the person at risk’ there can be no duty of care owed for the actions of a third party. In this case no duty of care was owed.

This was qualified in Selwood v Durham County Council (2012) (CoA); assumption of responsibility could be inferred from the circumstances of the case as well as any conduct or words. This can be inferred expressly or impliedly.

An example in which the defendant was found liable for the acts of a third party because of their relationship with the claimant and a specific assumption of responsibility for the claimant is Swinney v Chief Constable of Northumbria (No 2)(1999) (CoA).

Swinney became a police informant when she gave information to the police about the killing of a policeman. She was promised that her name would be kept secret. A document containing her details was stolen from the police. Scared of the consequences the informant suffered psychiatric illness and sued the police. The court held that the police did have a duty of care for an informant, there was sufficient proximity and they had specifically assumed responsibility for her safety. However, in this case the duty had not been breached by the theft of the information.

RELATIONSHIP OF CONTROL BETWEEN DEFENDANT AND THIRD PARTY

If a relationship of control exists between the defendant and the third party then a duty of care may be owed to the claimant (Home Office v Dorset Yacht (1970) (HoL)).

Officers overseeing a group of young offenders on Brownsea Island negligently allowed some of them to escape. They broke into a yacht club and stole a boat. The relationship between the Home Office (the original defendant) and the young offenders (the third parties) was one of the greatest control and the fact that they damaged the boats was the most likely consequence of allowing them to escape. In these circumstances a duty of care was owed to Dorset Yacht by the Home Office.

The case of Vowles v Evans (2003) (CoA) illustrates this exception in the context of sport. A scrum collapsed during a game of rugby and the referee failed to stop the match. One player was left in a wheelchair because of it. Evans, the referee, was held to have sufficient control over the players (the third parties) that he owed them all a duty of care to protect them from the actions of each other, specifically actions that broke the rules of the game and created a risk to other players. Players consented to injury sustained during play as long as the injury was not caused by negligent refereeing or playing.

DEFENDANT CREATES SOURCE OF DANGER THAT IS IGNITED BY THIRD PARTY

If the defendant created a foreseeable risk and the risk was ‘sparked’ by a third party the defendant may be liable for the damage (Haynes v Harwood (1936) (CoA)).

Harwood had left his horses untethered on the street. Whilst they were left unattended some children threw rocks at them and the horses bolted. Haynes, a policeman, was injured trying to catch them. Harwood was liable for the actions of the children (the third parties) because he had created a foreseeable risk (that the horses would bolt if left untethered) which had been sparked by the children throwing rocks.

In Topp v London County Bus (1993) (CoA) a minibus was left unlocked outside a pub with the keys in the ignition. Someone took the minibus for a joy ride and killed a pedestrian. In this case the court held that the minibus posed no more risk than any other vehicle parked on the street and the defendant was not liable for the actions of the third party.

KNOWN DANGER OF 3RD PARTY IS IGNORED BY DEFENDANT

If the defendant knew, or should have known, about a danger created by a third party and did not deal with the danger they may be liable for the actions of the third party (Smith v Littlewoods (1987) (HoL)).

Smith’s property was damaged when vandals broke into an empty cinema next door (owned by Littlewoods) and started a fire. The court found that the risk of this happening was not reasonably foreseeable and therefore Smith was not owed a duty of care. Littlewoods had taken reasonable precautions to stop people entering their empty property. The only thing they could have done to completely prevent any danger was have round-the-clock security and this was deemed out of proportion to the risk. Therefore Smith was not liable for the actions of the third parties.

In Clarke Fixing v Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council (2001) (CoA) a very similar thing happened. Vandals broke into an abandoned property owned by the council and started a fire which damaged the claimant’s neighbouring property. However, in this case the council knew that people had been breaking in and starting fires on several previous occasions. The claimant had even complained to them about it. Therefore the risk was known and foreseeable and they were liable for the actions of the vandals.

RESCUERS

If someone attempting to rescue or reduce a danger is injured the law will look favourably on them and usually find that the person who created the risk owes them a duty of care. Compare these two cases; Haynes v Harwood (1935) (CoA) and Cutler v United Dairies (1933) (CoA).

| Harwood had left his horses untethered on the street. Whilst they were left unattended some children threw rocks at them and the horses bolted. Haynes, a policeman, was injured trying to catch them. He was classified as a rescuer and was able to sue Harwood for creating the risk which had led to his injury. |

Cutler was also injured trying to catch a runaway horse. However, by the time Cutler had caught the horse and it had injured him the horse had come to a standstill in the middle of a field and posed no immediate danger to anyone. Therefore he was not considered a ‘rescuer’ by the law and he was owed no duty of care. |