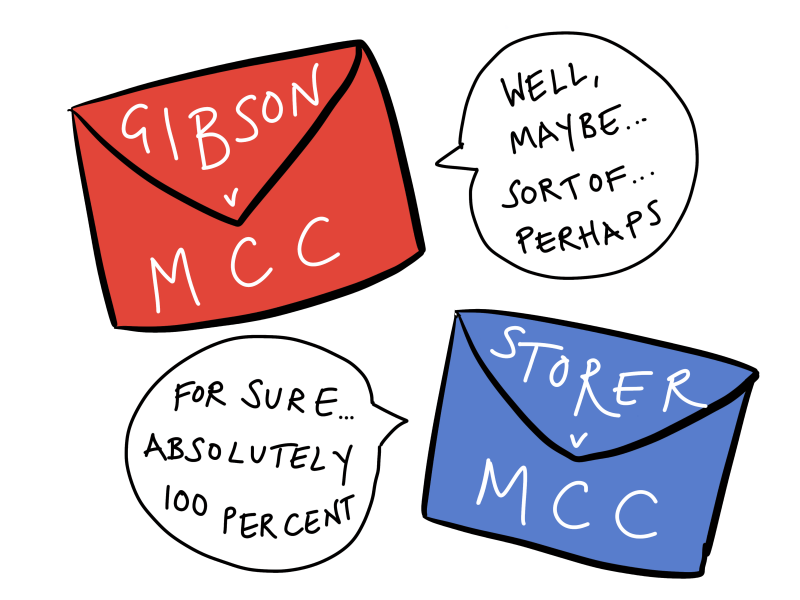

Case Summary…the difference between Gibson and Storer v Manchester City Council

What is the difference between Gibson v Manchester City Council and Storer v Manchester City Council?

Why was one claimant found to have had a valid contract with the Council and the other had only been made an invitation to treat?

Let’s compare the facts of the cases.

Both made it to the Court of Appeal, and Gibson the House of Lords, even though they were fairly simple cases of offer and acceptance. This is because they were test cases. There were hundreds of other tenants in the same position when Councils changed from Conservative to Labour in the 1971 elections.

The Conservative Council had been following a policy of offering council houses for sale to tenants. When Labour was voted in they reversed this policy and tried to end any negotiations with council tenants that had not yet led to the final sale of their property.

Here are the facts of both cases…

November 1970 – Manchester City Council send out brochures to tenants who are interested in buying their houses about a possible sale and the mortgages on offer from the council.

Both Gibson and Storer fill in the form entitled ‘Please inform me of the price of buying my council house’ and return it to the Council.

Jan/Feb 1971 – The Council send Storer and Gibson the following letter…the following is the version sent to Gibson but they received the same letter, the only difference being the price of their respective houses.

‘Dear Sir,

Purchase of Council House

Your Reference Number 8246303

I refer to your request for details of the cost of buying your Council house. The Corporation may be prepared to sell the house to you at the purchase price of £2,725 less 20% = £2,180 (freehold).

Maximum mortgage the Corporation may grant : £2,177 repayable over 20 years.

…

This letter should not be regarded as a firm offer a mortgage.

If you would like to make formal application to buy your Council house please complete the enclosed application form and return it to me as soon as possible.

Yours, faithfully,

(Sgd) H. R. Page

City Treasurer’

|

Feb 12th 1971 – the Council move Gibson’s house from the list of Council maintained properties to a list of ‘pending sales’. March 5th 1971 – Gibson fills in and returns the application form but leaves the box for ‘Price’ empty. He requests a reduction in the price because of work that needs to be done on the tarmac path. He also states that he would like to take out a mortgage with the Council. March 12th 1971 – the Council reply stating that the condition of the house had already been taken into consideration when setting the price so there would be no reduction. March 18th 1971 – Gibson replies, ‘I would be obliged if you will carry on with the purchase as per my application already in your possession’. |

February 11th 1971 – Storer fills in and returns the application form, stating, ‘I now wish to purchase my Council house’, and asks for a mortgage. March 9th 1971 – The Town Clerk writes to Storer; ‘Dear Sir: Sale of Council House. I understand you wish to purchase your Council house and enclose the agreement for sale. If you will sign the agreement and return it to me, I will send you the agreement signed on behalf of the Corporation in exchange.’ Enclosed with the letter was a form headed:- ‘City of Manchester. Agreement for Sale of a Council House’. The Council had filled in details such as the name of the purchaser, the address of the property, the price, the mortgage, amount, and the monthly repayments. They had only left blank the date when the tenancy would cease and mortgage repayments would commence. March 20th 1971 – Storer signs and returns but without filling in the date that the tenancy ends. |

May 1971 – election

July 1971 – policy of council house buying is ended by the new Labour council.

The Decision in Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 1 WLR 1403

The Court of Appeal found in Storer’s favour. There had been a valid offer and acceptance and the Council were ordered to perform specific performance and sell Storer his house.

The Court held that the form ‘Agreement for Sale of a Council House’, sent to Storer on March 9th by the Town Clerk, was a valid offer and Storer’s return of the application on March 20th was valid acceptance of that offer. The Council had argued that their form was only an invitation to treat but the Court disagreed; the wording ‘If you will sign the agreement and return it to me, I will send you the agreement signed on behalf of the Corporation in exchange’ was sufficiently clear and certain to constitute a valid contractual offer.

The Council also argued that there could be no sale because there had been no exchange of contracts as was normal in a sale of land (the Council had changed to Labour before the Council’s signed copy could be sent to Storer). However, the Court held that because the standard application form, ‘Agreement for Sale of a Council House’, had been specifically designed by the Council to avoid the full legal formalities of a normal land sale this was not a valid argument. The Council’s intention had been to make the sale of council houses easier by doing away with some formalities such as exchange of contracts, they could not then argue that there had to be an exchange for a valid sale. Once Storer had returned the form his acceptance the contract had been formed, it was not reliant on the Council returning their signed form.

Lastly they stated that the contract was not valid because Storer had left blank the date on which the lease would end, therefore not all of the material terms had been agreed. The Court dismissed this argument; the date was merely an administrative formality, its absence did not invalidate the whole contract.

In his judgment Lord Denning MR was keen to take a less formal and rigid view of offer and acceptance and emphasised the need to look at the conduct and intention of the parties. He stated;

‘In contracts you do not look into the actual intent in a man’s mind. You look at what he said and did. A contract is formed when there is, to all outward appearances, a contract. A man cannot get out of a contract by saying ‘I did not intend to contract’ if by his words he has done so. His intention is to be found only in the outward expression which his letters convey. It they show a concluded contract, that is enough.’

The Decision in Gibson v Manchester City Council [1979] UKHL 6

Both the Trial Judge and Court of Appeal decided in Gibson’s favour and ordered specific performance, i.e. that the Council had to fulfil the sale of the house.

In the Court of Appeal Lord Denning argued, as he had done in Storer, that the rigid formula of offer and acceptance did not always truly reflect the intentions of the parties. The court should look at the communication between the parties as a whole and decide whether they have come to an agreement. In this case he stated that offer and acceptance could be inferred from the conduct of the parties. His opinion was that it had clearly been the intention of both parties to buy/sell the house and that all material terms had been agreed, therefore there was a valid contract.

Ormrod L. J. argued that the letter, ‘Purchase of Council House’, from the Council to Gibson was an unconditional offer. The filling in of the application was valid acceptance by Gibson.

Geoffrey Lane L. J. dissented and stuck to a more traditional approach to offer and acceptance. In his view there was no valid contract between the parties.

The House of Lords disagreed with the Court of Appeal and Denning’s use of an holistic view of offer and acceptance, finding against Gibson. In their opinion the letter, ‘Purchase of Council House’ sent by the Council to Gibson in February 1971, did not constitute an offer, it was merely the start of a negotiation. Lord Diplock described the wording, that they ‘may’ be willing to sell the house, as ‘fatal’ to the argument that the Council was making a solid, contractual offer. Instead their letter was an invitation to treat, asking Gibson to make an offer of purchase which they could then accept or reject.

The Court of Appeal has also misinterpreted that part of the Council’s letter that read, ‘This letter should not be regarded as a firm offer a mortgage’. Their interpretation that this meant the other part of the letter, regarding the purchase price of the house, was a firm offer was incorrect. The meaning of one part could not be used to affect the plain meaning of another part.

The conduct of the parties was equivocal and not certain enough to infer offer and acceptance. Moving the house from the list of tenanted houses to the list of houses for sale did not indicate that they specifically intended to sell the house to Gibson. In addition there was not enough certainty regarding the mortgage; would he be granted the mortgage? Would he definitely go ahead with the mortgage that was offered? If this was a valid offer and acceptance would he have been legally bound to proceed with the mortgage offered by the Council?

The House of Lords’ conclusion was that there had been no valid offer, the wording of the Council was too unclear and uncertain. Gibson’s argument that he had accepted the Council’s offer in his letter of March 18th was therefore invalid as it was impossible to accept an offer that had never been made. There was also no mileage in arguing that it was Gibson’s letter that was an offer because there had been no acceptance of that offer by the Council.

The main difference between Gibson and Storer is the fact that Storer had been sent and returned the ‘Agreement for Sale of a Council House’ form which was deemed a valid offer. Gibson had not yet done so and had therefore tried to argue that the initial, ‘Purchase of Council House’, letter was a valid offer. Primarily based on the difference in the wording of the two documents one was held to be a valid offer and the other was not.

To read more about the difference between offers and invitations to treat click here.