JUMP TO:

BILATERAL & UNILATERAL OFFERS: Errington v Errington & Woods | Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball

INVITATIONS TO TREAT: Gibson v MCC, Storer v MCC | Harvey v Facey | Partridge v Crittenden | Grainger v Gough | Bowerman v ABTA | Lefkowitz v Great Minneapolis Surplus Store | Fisher v Bell | Pharmaceutical Society of GB v Boots | Spencer v Harding | Harvela v Royal Trust Co of Canada | Blackpool & Fylde Aero Club v Blackpool BC | Payne v Cave | Barry v Davies

COMMUNICATION OF AN OFFER: Taylor v Laird

REVISE | TEST

OFFERS AND INVITATIONS TO TREAT

An offer is ‘an expression of willingness to contract on certain terms, made with the intention that it shall become binding as soon as it is accepted by the person to whom it is addressed.’

Edwin Peel, Treitel on the The Law of Contract (15th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2020)

‘An offer is an expression of willingness to contract, made with the intention that it shall be binding upon the person making it, as soon as it is accepted by the person to whom it is addressed.’

Air Transworld Ltd v Bombardier Inc [2012] EWHC 243, para [75]

BILATERAL AND UNILATERAL OFFERS

All contractual offers are either bilateral or unilateral.

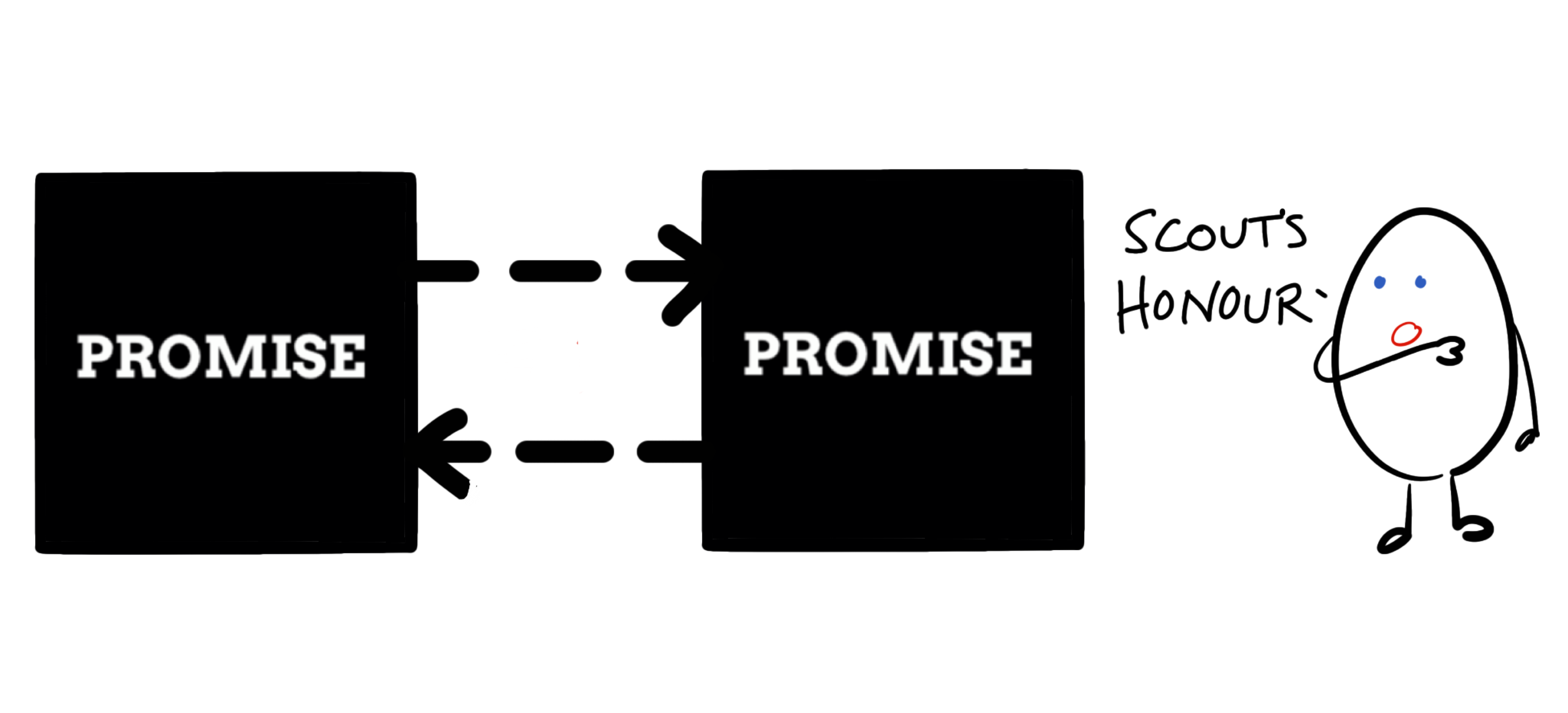

BILATERAL OFFERS

Most contractual offers are bilateral. The offeror promises something in return for a promise of something from the offeree.

For example, the offeror offers a coat to the offeree for £5. In exchange the offeree promises to pay £5 to the offeror.

A bilateral offer is made by one party to one other party.

|

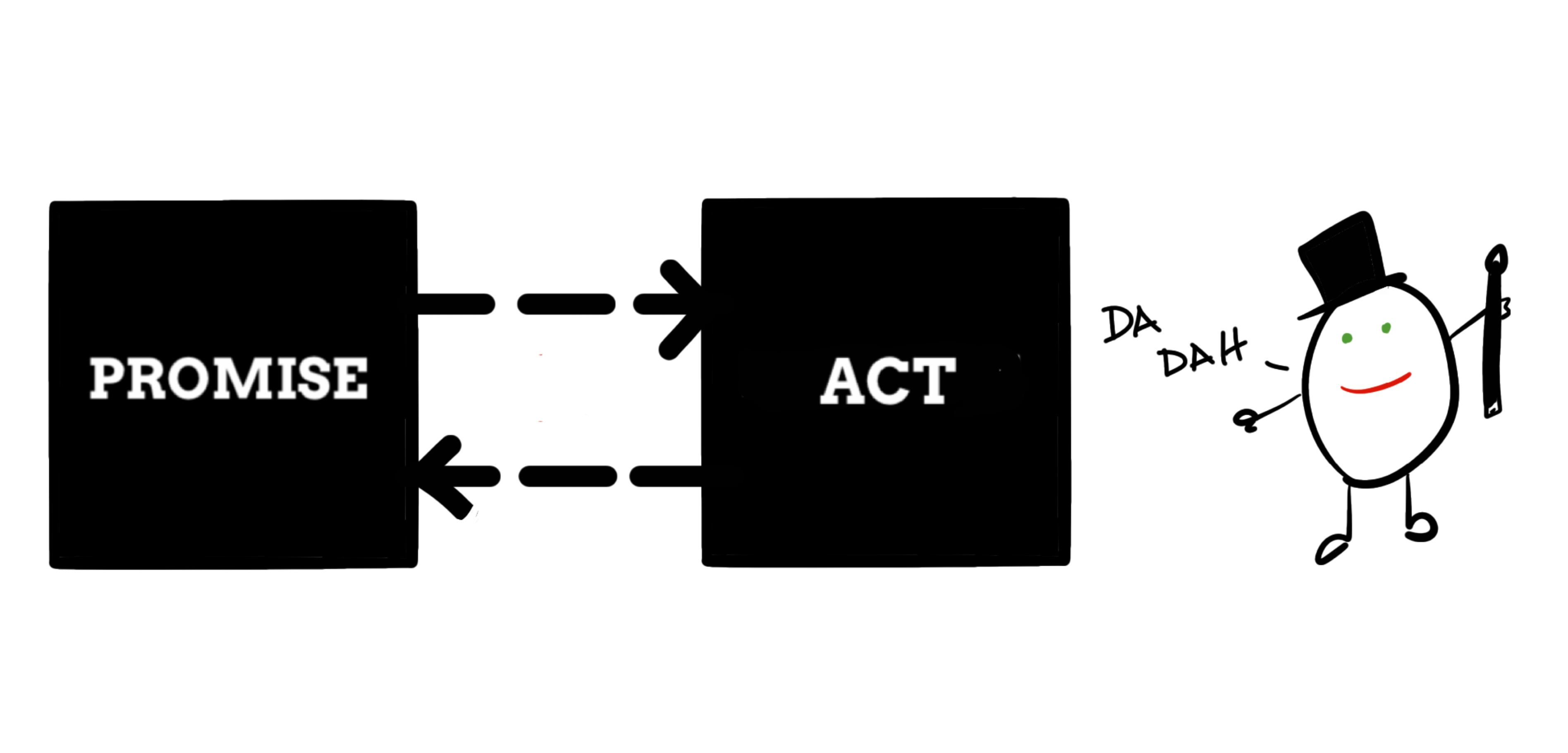

UNILATERAL OFFERS

In a unilateral offer the offeror promises something to the offeree in return for the performance of an act by the offeree.

For example, a Wanted Poster is a good example of a unilateral offer, a reward is offered in return for the completion of an act (bringing in the criminal).

A unilateral offer can either be made to one party or multiple parties, even ‘to the entire world’.

|

Another key distinction between a bilateral and unilateral contract is that in a bilateral contract the exchange of promises takes place simultaneously whereas in a unilateral contract the making of the promise and the performance of the act usually occur at different points.

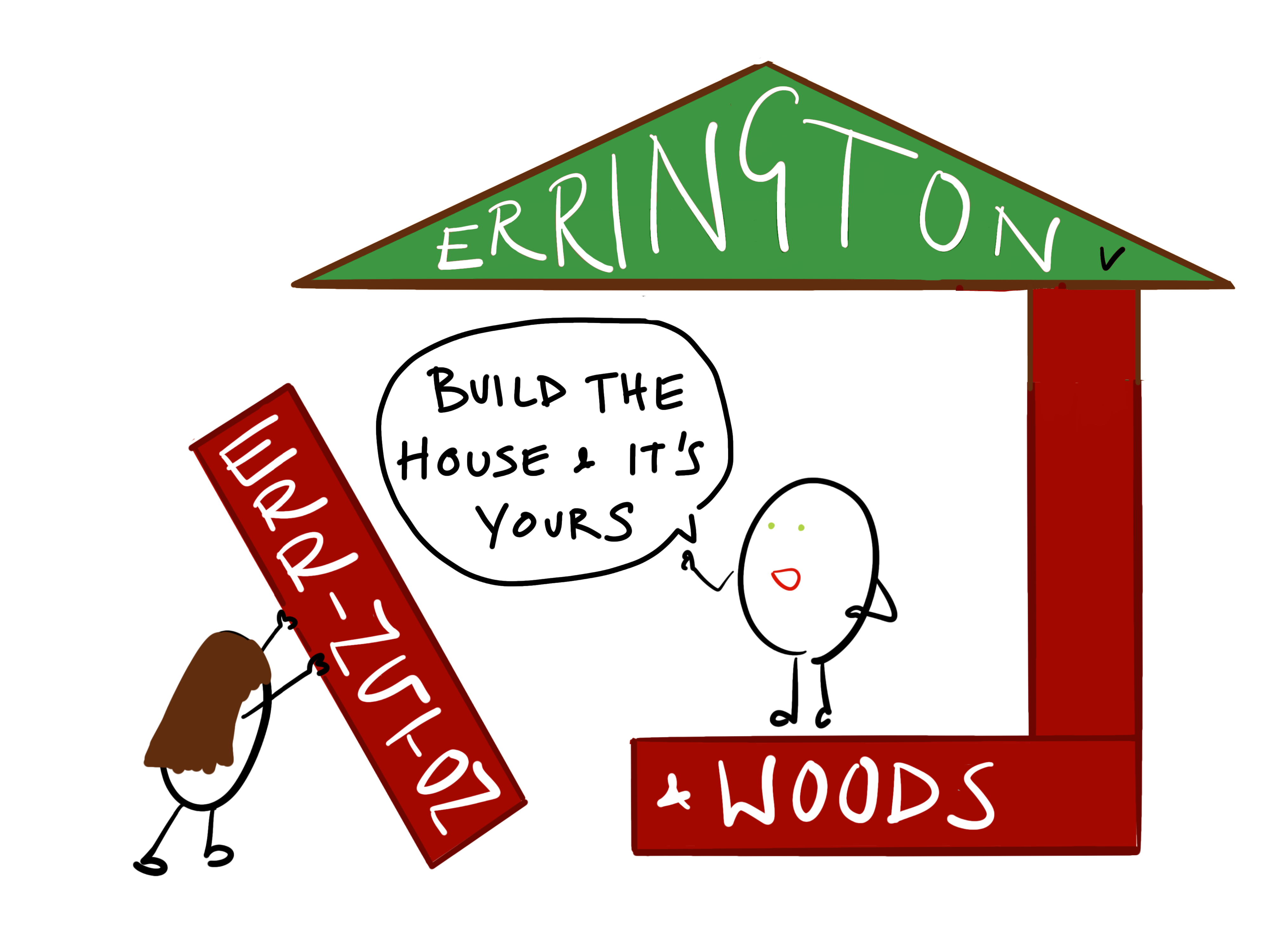

An example of a unilateral offer made to one party is Errington v Errington & Woods (1952) (CoA).

Mr. Errington paid the deposit on a house and offered to give it to his son and daughter-in-law if they paid the mortgage instalments. Once the act of paying all of the instalments had been completed then the house would belong to them. The couple split up but the daughter-in-law continued to make the repayments. Mr. Errington died and his widow tried to claim the house as her own but the court held that it would be unfair to revoke the offer. If the daughter-in-law finished making repayments she would own the house as originally offered. This case also arises in Revocation.

An example of a unilateral offer made to multiple parties is Carlill v Carbolic Smokeball Company (1893) (CoA).

An advert for an anti-influenza smokeball offered £100 to anyone who used the ball according to the instructions but still caught the flu. Mrs Carlill, having read the advert, bought and used a smokeball but it didn’t work and she became ill. When she claimed the £100 the company refused to pay. The court held that the defendant had made a unilateral offer ‘to all the world’; their advert had offered £100 in return for a specified an act, buying and using a smokeball that didn’t work. They had also shown intention to be bound by stating that £1,000 was put aside in an account ready for any claimants who may use the ball and still fall ill. Mrs Carlill had fulfilled the act and therefore they were bound to their offer and must pay Mrs Carlill £100.

See ‘Case Summary…the background to Carlill v Carbolic’ for more detail on this seminal case.

INVITATIONS TO TREAT

Sometimes what seems like an offer is in fact an invitation to treat.

An invitation to treat, instead of being an offer, is an invitation to the other party to make an offer. Unlike a party making an offer, a party communicating an invitation to treat does not intend to be bound by their statement.

There are 5 specific scenarios where we must distinguish between offers and invitations to treat…

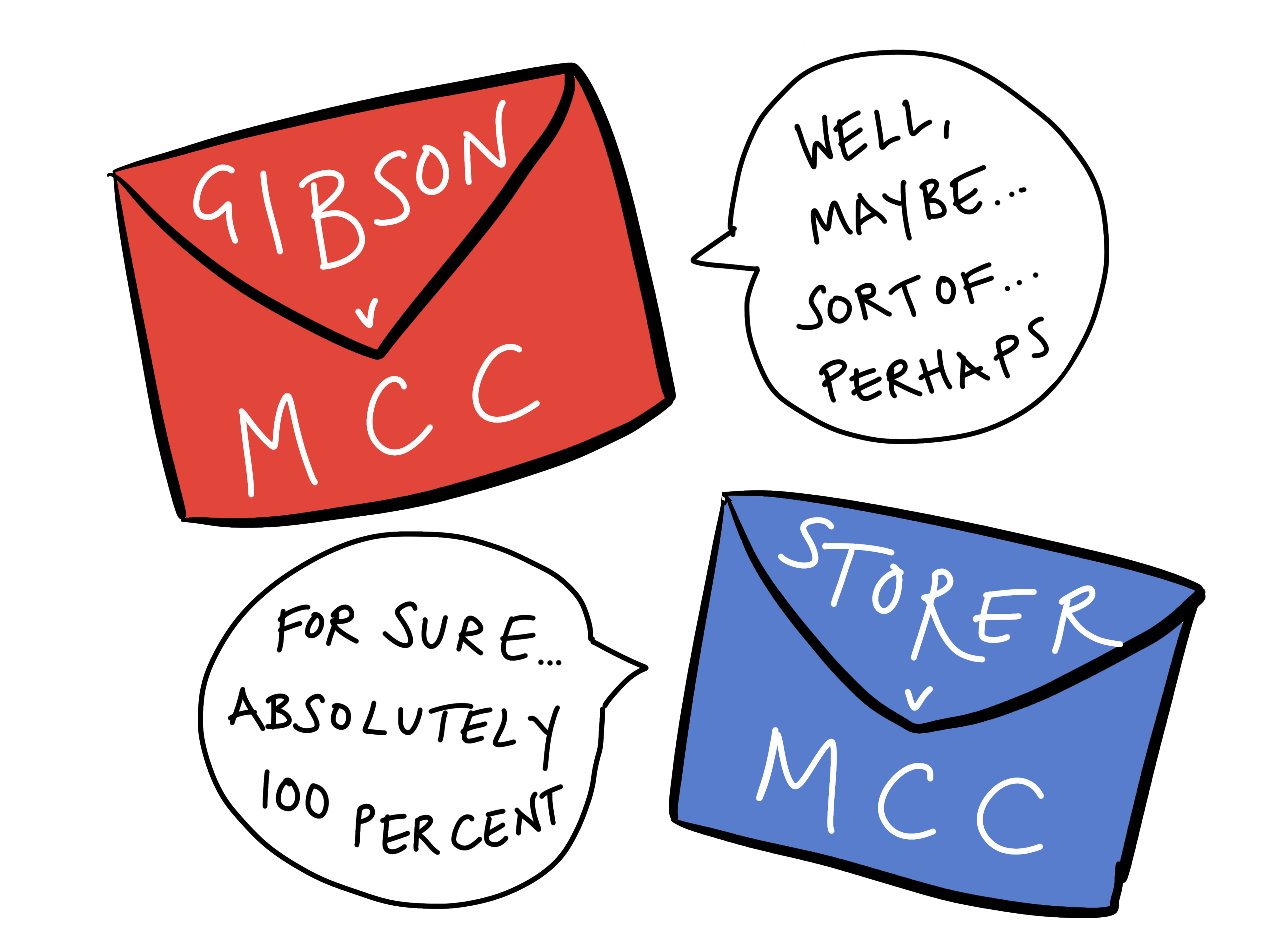

UNCERTAIN OFFERS

If the wording of an offer is not CLEAR and CERTAIN then it cannot be a valid offer. Words such as ‘might’, ‘may’ or ‘perhaps’ could indicate that this is an invitation to treat and that the party did not intend to be bound.

Compare the two cases below…

| In Gibson v Manchester City Council (1979) (HoL) Mr. Gibson was sent a letter by the Council stating that they ‘may be prepared’ to sell him his council house at the purchase price. When the newly elected council refused to sell Mr. Gibson his house he sued for breach of contract. The House of Lords held that the letter did not constitute a firm offer and did not state a specific price, it was therefore an invitation to treat. |

In Storer v Manchester City Council (1974) (CoA) the council had offered Mr. Storer the opportunity to buy his council house. He had agreed and all details had been arranged apart from the date upon which his lease would end and mortgage payments would begin. The newly elected council tried to reverse the offer of their predecessor but the Court of Appeal held that there was a binding contract; there had been a valid, clear and certain offer made by the previous council which had been accepted by Mr. Storer. |

To read an in-depth case summary and comparison of Gibson v MCC and Storer v MCC click here.

The case of Harvey v Facey (1893) (PC) is another good example. Mrs. Facey owned a piece of land called Bumper Hall Pen in Jamaica. Mr. Harvey asked Mr. Facey to send him a telegraph stating whether he was willing to sell Bumper Hall Pen and what the lowest price was that he would accept for the property. Facey replied stating £900. Harvey took this as an offer and accepted. When Harvey discovered that Facey was trying to sell the property to the city of Kingston he sued for breach of contract. However, the Privy Council found that Facey had made no clear offer to sell, only an invitation to treat. Facey’s telegram had not stated any clear intention to be bound, he was simply responding to a request for information. Harvey’s telegram stating that he would buy for £900 was an offer that Facey rejected.

ADVERTS

Most adverts are invitations to treat and not offers (Partridge v Crittenden (1968) (HC)).

The defendant had placed an advert for ‘live birds’ in a specialist journal. He was charged with ‘offering for sale’ live birds in contravention of s.6(1) Protection of Birds Act 1954. However, the court ruled that he was not guilty because his advert was not an offer. Rather he had made an invitation to treat, the general public was being invited to make an offer.

In Grainger v Gough (1896) (HoL) this rule was explained. The defendant was a wine merchant who had sent out a wine catalogue and price list. When Grainger ordered some wine Gough refused to sell at the stated price. Grainger sued for breach of contract. The House of Lords found that the catalogue was an invitation to treat and not an offer. If all adverts, or catalogues, were offers then the seller would be legally bound to sell to anyone who had seen the advert. Bearing in mind that most sellers have limited stock this would be unreasonable. However, in obiter it was proposed that if the offeror was a manufacturer (who could make an unlimited amount) then this principle may not apply and their advert may constitute an offer.

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE

An advert that constitutes a unilateral offer is not an invitation to treat but an offer and the offeror will be bound by the terms of the agreement if someone performs the required act (Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Company (1893) (CoA)).

An advert for an anti-influenza smokeball offered £100 to anyone who used the ball but still caught the flu. This was held by the court to be a binding offer ‘to all the world’.

|

|

This principle was also applied in Bowerman v Association of British Travel Agents Ltd (1996) (CoA). Bowerman booked a holiday that was advertised as being covered by ABTA (insurance coverage from the travel association) in case of cancellation. When the holiday was cancelled ABTA claimed that this was an advert and therefore not a binding offer. The Court of Appeal disagreed; the advert was making a unilateral offer…buy this holiday and we will cover you if it is cancelled. Any ordinary person on the street would have read the advert in this way, therefore ABTA were bound by their offer.

Also consider the American case, Lefkowitz v Great Minneapolis Surplus Store (1957). A store placed an advert in a newspaper stating that a coat worth $139.50 would be available for sale at 9am on Saturday for only $1.00, ‘first come, first served’. The claimant was first to arrive on Saturday but the store told him that it was a house rule that such offers are intended for women only. The Supreme Court of Minnesota held that the advert was clear enough to be an offer requiring acceptance by performance. The claimant arrived first and should be entitled to buy the coat. The store could not subsequently add terms or ‘house rules’ to the offer.

GOODS ON DISPLAY

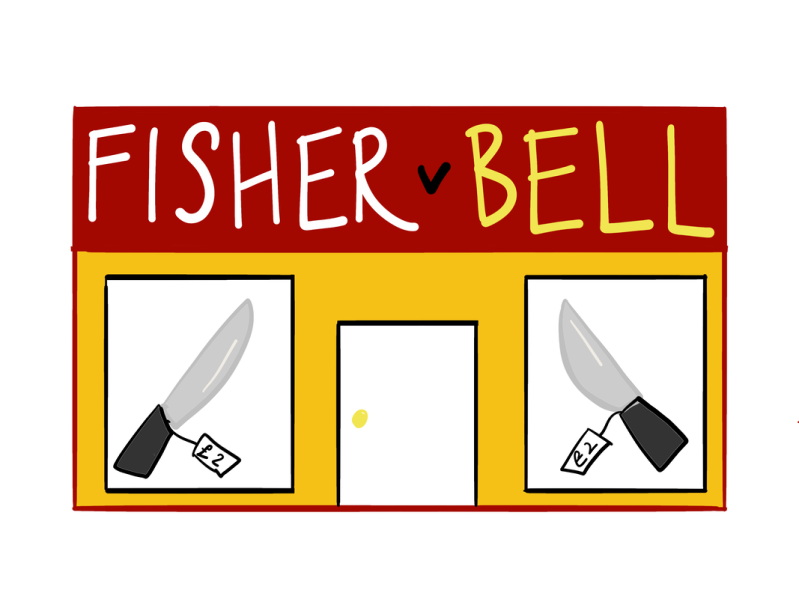

The general rule is that goods on display in shops are invitations to treat (Fisher v Bell (1961) (HC)).

A shopkeeper was charged with the offence of offering to sell knives under the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959. However, he was not found guilty because the knives in the shop window were an invitation to treat and not an offer. The customer would have to make an offer to the shopkeeper if they wanted to buy one.

After this case the statute was amended by the Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1961 to close this loop hole. The wording was amended to include weapons that a seller exposes or has in his possession for the purpose of sale or hire. Under this law Bell would have been found guilty.

This is still the case if the goods are available in a self-service shop (Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (1953) (CoA)). The customer makes the offer to buy when they take the goods to the counter. It will then be for the shopkeeper to accept or decline the offer.

There is a good public policy reason behind this rule. Were goods on display to amount to ‘offers’ customers might be regarded as accepting them by merely selecting goods around the shop. If this were the case a valid contract would be formed and the customer would technically be in breach of contract if they changed their mind and wanted to return the items before arriving at the checkout.

Automatic machines represent a standing offer, acceptance is activation of the machine (i.e. issuing a ticket). This principle was established in Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking (1971) (CoA) which involved a ticket machine at a car park barrier. For more on this case see the page on Exemption Clauses.

CALL FOR TENDERS

A call for tenders is not an offer but an invitation to treat. Instead, the submitted tender constitutes an offer (Spencer v Harding (1870) (Court of Common Pleas)).

Harding distributed a circular stating; ‘we are instructed to offer…for sale by tender the stock in trade of Messrs G Eilbreck and Co’. Spencer submitted the highest tender but it was refused. He was unable to sue for breach of contract because the call for tenders was only an invitation to treat and not an offer. It invited other parties to make an offer by submitting a tender, and as the court stated, ‘there was a total absence of any words to intimate that the highest bidder is to be the purchaser’. Therefore Spencer had not entered into a contract but had merely made an offer which was not accepted.

EXCEPTIONS TO THE RULE – SPECIFIC BIDS

If a call for tenders states that a specific bid (e.g. the highest) will be chosen then it does constitute an offer (Harvela Investments Ltd v Royal Trust Co of Canada (1986) (HoL)).

This is because the offeror has made a unilateral offer – a specific act (be the highest bidder) with intention to be bound – and the offeree has fulfilled the request.

In this case the defendant invited interested parties to buy shares in a competitive tender, stating that they would accept the highest ‘offer’ received by them which complied with the terms of their invitation. The claimants submitted the highest bid and the defendant was bound to accept it.

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE – COLLATERAL OFFERS

A call for tenders is accompanied by a collateral offer to at least consider all tenders which are submitted correctly (Blackpool and Fylde Aero Club Ltd v Blackpool Borough Council (1990)(CoA)).

A call for tenders was made by Blackpool BC. The deadline was 12pm on 17th March. BFAC submitted on 11am but their tender was never reviewed. The court said that while the Council was not obliged to accept BAFC’s specific tender they were duty bound to consider it.

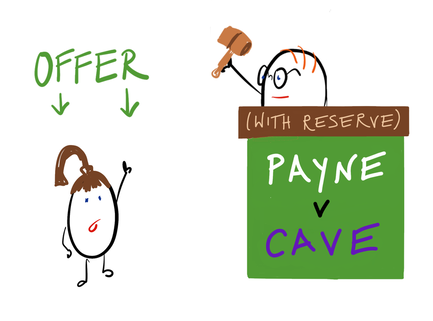

AUCTIONS

|

ITEMS WITH RESERVE PRICE

If an auction item has a reserve price then the auctioneer’s call for bids is an invitation to treat. The bidder makes the offer which the auctioneer can either reject or accept. The fall of the gavel is indication of acceptance (Payne v Cave (1789) (HC)).

This is now codified in s.52(2) Sale of Goods Act 1975.

|

ITEMS WITHOUT RESERVE PRICE

If an auction item does not have a reserve price then the auctioneer’s call for bids is an offer and the item must be sold to the highest, legitimate bidder. In Barry v Davies (2001) (CoA) the auctioneer refused to accept a bid of £200 from Davies for an item without reserve because the item was worth over £30,000. The auctioneer had made a unilateral offer to the highest bidder and therefore Davies’ bid had to be accepted.

This is now codified in s.57 Sale of Goods Act 1975. |

|

Like other adverts, an advert for an auction is an invitation to treat, there is no offer to sell particular goods or to hold the auction at all (Harris v Nickerson (1873) (HC)).

COMMUNICATING AN OFFER

A valid offer must be communicated to the offeree. They can then decide whether to accept or reject it (Taylor v Laird (1856 (Court of Exchequer)).

The captain of a ship voluntarily demoted himself to crew member. When the ship returned home the owner refused to pay him any salary at all, not as the captain nor crew member. Even though he had demoted himself his offer to change position had not been communicated to the ship’s owners and they had therefore not been given the opportunity to accept or reject his offer.

Communication can be done in writing, orally or implied from conduct, or a combination of these. A unilateral offer (e.g. Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Company (1893)) that is made to more than one person is instantly communicated to the whole world when it is made.