Case Summary…Is Stilk v Myrick (1809) still good law?

Is Stilk v Myrick still good law?

Stilk v Myrick (1809) (HC) is a contract law case dealing with consideration that all law students will have come across. It’s almost always juxtaposed to Hartley v Ponsonby (1857) (HC). It’s one of the older cases that students still have to learn today so how has it survived over 200 years of legal use?

What is consideration?

Let’s just revisit the classic definition of consideration from Currie v Misa…

‘some right, interest or benefit accruing to the party or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility, given, suffered or undertaken by the other.’ Lush LJ, Currie v Misa (1875) (Exchequer Chamber).

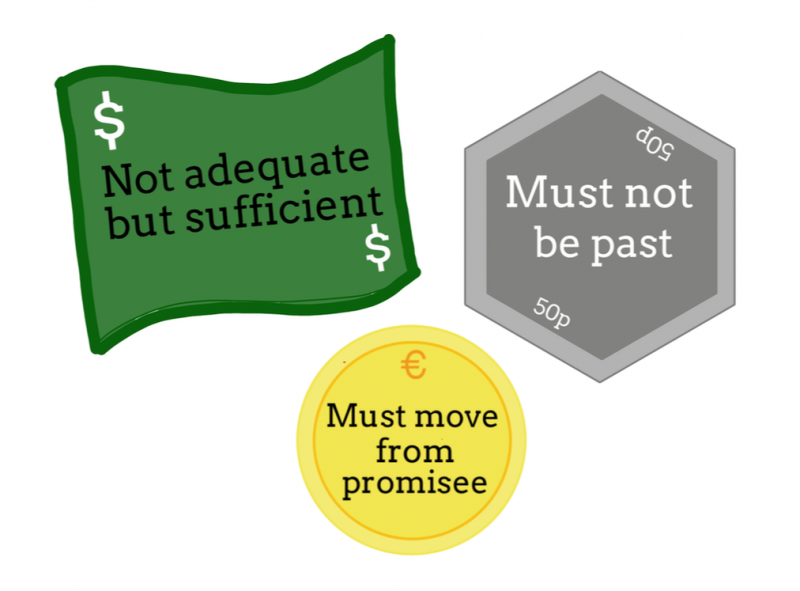

In other words consideration is something that must flow from both parties. otherwise one party would have made a gift to the other. The other rules of consideration are that it need not be adequate but must be sufficient, past consideration is not good consideration and consideration must move from the promisee.

The facts of Stilk v Myrick and Hartley v Ponsonby

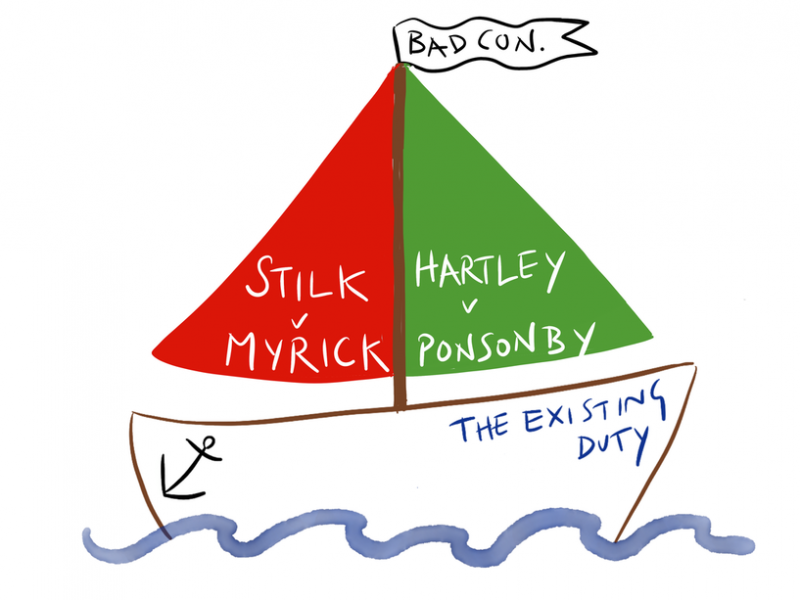

In Stilk v Myrick (1809) (HC) two people had deserted from a crew of 11 on a ship that was returning to England from the Baltic. The captain couldn’t find replacements so offered to share the deserters’ wages between the rest of the crew if they agreed to sail the ship back home. However, when they returned home the captain refused to pay them the extra wages. Stilk, one of the crew members, sued. His case was unsuccessful; the court held that the crew’s existing contractual duty was to sail the ship home and that therefore they had not provided any fresh consideration for the captain’s promise to pay more. There had been no valid arrangement and the crew were only entitled to their original wages.

In Hartley v Ponsonby (1857) (HC) 19 out of a crew of 36 had deserted and the captain again offered the remaining men extra money to sail the boat home. However, in this case because of the severe reduction in the crew the remaining men would have been entitled to abandon the voyage and by agreeing to continue they went beyond their existing duty, taking on a much more difficult and dangerous journey. They were therefore entitled to the extra pay because they had provided fresh consideration for the captain’s promise to pay more.

What is the legal rule from Stilk v Myrick?

The main principle of law that arose from Stilk v Myrick was that the performance of an existing contractual duty is not good consideration for a further promise. This comes from Campbell’s law report. However, there was another law report of the same case written by Espinasse. His report focused more on the public policy reasons behind the decision. The courts wanted to discourage sailors from forcing captains to offer them better wages in circumstances such as Stilk v Myrick and Hartley v Ponsonby. In an era before the law of economic duress the courts had to use a lack of consideration instead.

Why do we now follow the legal rule from Campbell’s report rather than Espinasse? Partly it may be that Campbell’s version provides the courts with a rule that has a much wider application in law than Espinasse’s. The public policy rule only really applies to the specific area of sailors and captains. Law reports in the early 19thc. were much less formal and standardised and neither reporter was known for their complete accuracy! However, perhaps it is also because Espinasse had an even worse reputation than Campbell. Campbell was accused of going beyond mere factual reporting, i.e. sometimes adding his own interpretation to events. However, as Pollock CB (a later 19thc. judge) stated, Espinasse only heard half of what went on in court and reported the other half!

Has Stilk v Myrick been challenged by the courts?

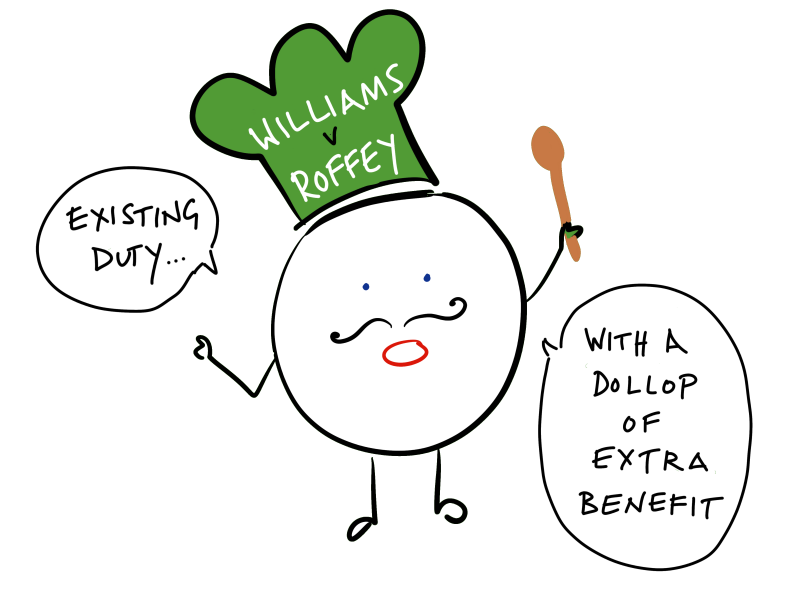

The case of Stilk v Myrick was most recently challenged in the case of Williams v Roffey (1991) (CoA). Williams had been commissioned to refurbish a block of flats. In this agreement between Williams and the property owners, there was a penalty clause for late completion (meaning that Williams would have to pay an amount for being late). Williams subcontracted Roffey to do some carpentry work like installing windows within the block of flats. . When it became apparent that Roffey was running behind schedule on the carpentry work, Williams offered Roffey additional money to speed up and finish his existing work obligations on time. Later, Roffey tried to claim this additional amount from Williams. Williams refused to pay on the grounds that Roffey had provided no extra consideration for his promise to pay more. Completing the work on time was part of the initial promise, nothing more was given for additional payment. However, the court, rather than following the strict interpretation of consideration as set out in Stilk v Myrick, held that a “practical advantage” had been gained by Williams (not having to pay the penalty for missing the deadline) so Roffey was entitled to the extra payment even though they had only fulfilled their existing duty.

How did Stilk v Myrick survive Williams v Roffey?

The question of consideration

The issue around consideration that arose in Williams v Roffey can be easily demonstrated by comparing the case to Hartley v Ponsonby? Hartley v Ponsonby represents a more traditional exchange of consideration; the captain offered the benefit of higher wages and the sailors in return offered the detriment of doing the work of all of the men who had deserted. In Williams v Roffey Williams promised the benefit of more money to Roffey and gained the benefit of the work being done in time but Roffey had suffered no extra detriment.

The judges’ reasoning

So how did the three Court of Appeal judges who sat on the case of Williams v Roffey manage to argue that Stilk v Myrick is still good law even though they seem quite similar?

All differ slightly in their reasoning. Let’s look at each one in turn…

Glidewell LJ argued that there was no reason why a rule first stated over 200 years ago during the Napoleonic Wars, designed for the rigours of seafaring life, should not be subject to ‘a process of refinement and limitation in its application in the present day’.

He felt comfortable in distinguishing Stilk v Myrick from Williams v Roffey. He believed that in Stilk v Myrick the captain had gained no extra benefit from his promise of further payment, presumably because the sailors were expected to sail the ship home anyway. In Williams v Roffey the promisor had gained the benefit of the work being done on time and avoiding a penalty clause. It did not matter that the promisee had suffered no further detriment.

He disagreed with counsel for the defence’s argument that consideration had not moved from the promisee (one of the rules of consideration set out in Tweddle v Atkinson (1861)). Glidewell LJ argued that this was more of a rule regarding privity of contract and there was clearly a contract between the two parties. He quoted Chitty on Contracts…

‘the requirement that consideration must move from the promisee may equally be satisfied where the promisee confers a benefit on the promisor without in fact suffering any detriment’.

So it was not a problem that only Williams had gained a benefit from the extra promise but Roffey had suffered no benefit. In Stilk v Myrick the captain had not gained anything and the sailors had not suffered any detriment.

Russell LJ held that ‘the rigid approach to the concept of consideration to be found in Stilk v Myrick is either necessary or desirable’. but was still good law because ‘a gratuitous promise, pure and simple, remains unenforceable’.

He argued that in more modern times a practical benefit (consideration) should be readily found from the intention of the parties as long as the parties were of equal bargaining power and there was no duress or fraud. In other words, the freedom to contract outweighs the strict interpretation of Stilk v Myrick. In Williams v Roffey both parties were in agreement that the new arrangement benefited them and therefore this was sufficient to satisfy the requirement for consideration – times had moved on since Stilk v Myrick.

The third judge, Purchas LJ, felt that Stilk v Myrick was an exceptional case that involved public policy issues regarding contracts at sea but he was not prepared to overrule two cases (Stilk v Myrick and Harris v Watson (1791)*) ‘of such veneration’ made by judges ‘of such distinction’. He went on to say that the cases ‘form a pillar stone of the law of contract’.

* Harris v Watson (1791) Peake 102 was a similar case to Stilk v Myrick and Hartley v Ponsonby. The master and commander of a ship sailing from England to Lisbon had offered the claimant extra wages to induce him to work harder and steer the ship whilst it was in danger. The court found in the commander’s favour on public policy grounds. It was a sailor’s duty to sail the ship during dangerous periods even without the promise of more money. If not sailors might be encouraged to put ships in danger in order to force captains to offer extra money.

However, he was willing to distinguish Williams v Roffey, arguing that as long as both parties gain a benefit it is not necessary that both parties suffer a detriment.

Criticisms of Williams v Roffey

The decision in Williams v Roffey has been criticised – one example is by Colman J who in obiter dicta comments in South Caribbean Trading Ltd v Trafigura Beheer BV [2005] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 128 argued that he would not have followed the judgment if he has not been bound by the fact it was a Court of Appeal case. He particularly felt that the fact that there had been no consideration moving from the promisee meant that there had been no valid agreement.

The decision has also created some confusion as to whether the “practical benefits” argument can apply to promises to accept less. Contract law has struggled with the circumstances in which part payment of a debt will relieve the debtor of their obligation to pay the rest of the sum. Read more on Part Payment of Debt & Promissory Estoppel. In Re Selectmove Ltd [1993] EWCA Civ 8, Gibson LJ said that Williams v Roffey Bros only applies where work was done or goods supplied. To extend it to debts would go against Foakes v Beer, which expressly said that a practical benefit was not good consideration in law.

Conclusion

So, in conclusion, Stilk v Myrick is still good law but would only be used in very particular circumstances in which there has been no real benefit to the promisor in exchange for their promise.