JUMP TO: NOT ADEQUATE BUT SUFFICIENT – Chappell v Nestlé | Thomas v Thomas | White v Bluett | Hamer v Sidway – PAST CONSIDERATION IS NOT GOOD CONSIDERATION – Eastwood v Kenyon | Roscorla v Thomas | Lampleigh v Brathwait | Re Casey’s Patents | Pao On v Lau Yin Long – CONSIDERATION MOVES FROM PROMISEE – Tweddle v Atkinson – EXISTING DUTIES AS CONSIDERATION – Stilk v Myrick | Hartley v Ponsonby | Williams v Roffey | Scotson v Pegg | The Eurymedon | Collins v Godefroy | Ward v Byham | Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan County Council – FORBEARANCE TO SUE – Wade v Simeon | Cook v Wright

CONSIDERATION

Consideration is the term given for the detriment or benefit exchanged by each party in a contract. All contractual promises must be supported by consideration and both the offeror and offeree must offer consideration otherwise the transaction is a gift and not a legally binding contract.

Consideration was defined as ‘some right, interest or benefit accruing to the party or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility, given, suffered or undertaken by the other.’

Lush J, Currie v Misa (1875) (Exchequer Chamber) – read more about this case here.

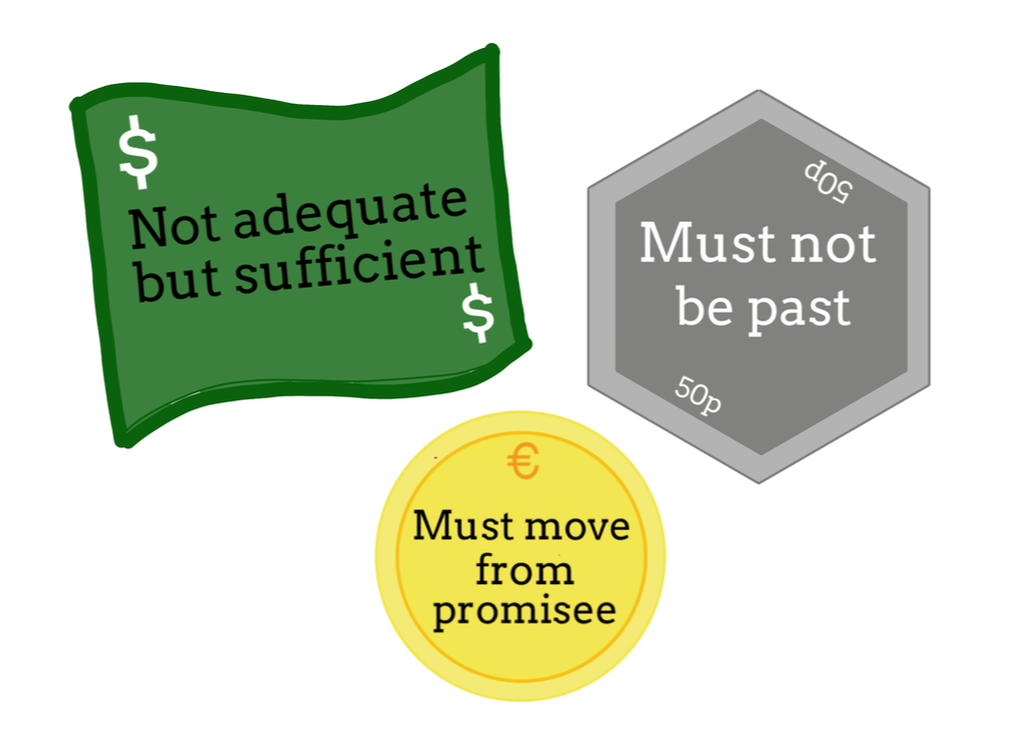

There are several rules that govern consideration:

CONSIDERATION NEED NOT BE ADEQUATE…

Consideration does not have to be ‘adequate’ or equate to the true market value of the other party’s promise. Contract law is not concerned with whether or not parties are exchanging things of equivalent value (i.e. making a fair bargain) so long as the two parties are happy with the value of the promises they are exchanging.

Even empty chocolate bar wrappers can be valid consideration…

In Chappell and Co Ltd v Nestle Co Ltd (1960) (HoL) Nestlé was offering a free music record to anyone who sent in three chocolate bar wrappers and 1s 6d. Chappell owned the copyright to the music being offered so was legally owed a percentage of the amount Nestlé were charging. Even though they were just thrown away by Nestlé, Chappell successfully argued that the wrappers formed part of the amount and therefore Nestlé owed Chappell a proportion of their value.

‘A contracting party can stipulate for what consideration he chooses. A peppercorn does not cease to be good consideration if it is established that the promisee does not like pepper and will throw away the corn.’ Lord Somervell, Chappell and Co Ltd v Nestlé Co Ltd (1960)

Also consider Thomas v Thomas (1842) (HC). A widow promised to pay the executors of her husband’s estate £1 per year and to keep a property in good repair in exchange for being able to live there until she died. This was considered adequate consideration. As such, the executors could not dispossess the widow.

…BUT MUST BE SUFFICIENT

Consideration must be sufficient, in other words it must have some legal value (White v Bluett (1853) (Exchequer Chamber)).

A father offered to forget his son’s debts if the son refrained from complaining about the father’s will. When the father died his executors took the son to court for non-payment of his debts. The court did not believe that the son had provided sufficient consideration to have his debts forgotten; the father was entitled to write anything in his will and the son had no legal right to complain about it, so refraining from doing so was of no legal value.

In comparison, in the American case of Hamer v Sidway (1891) an uncle had offered his nephew money if he gave up drinking, smoking, swearing and playing cards. Upon the uncle’s death his widow refused to pay but the court ruled that as the nephew had a legal right to engage in all of these activities, refraining from doing them was abandoning a right and this constituted sufficient consideration.

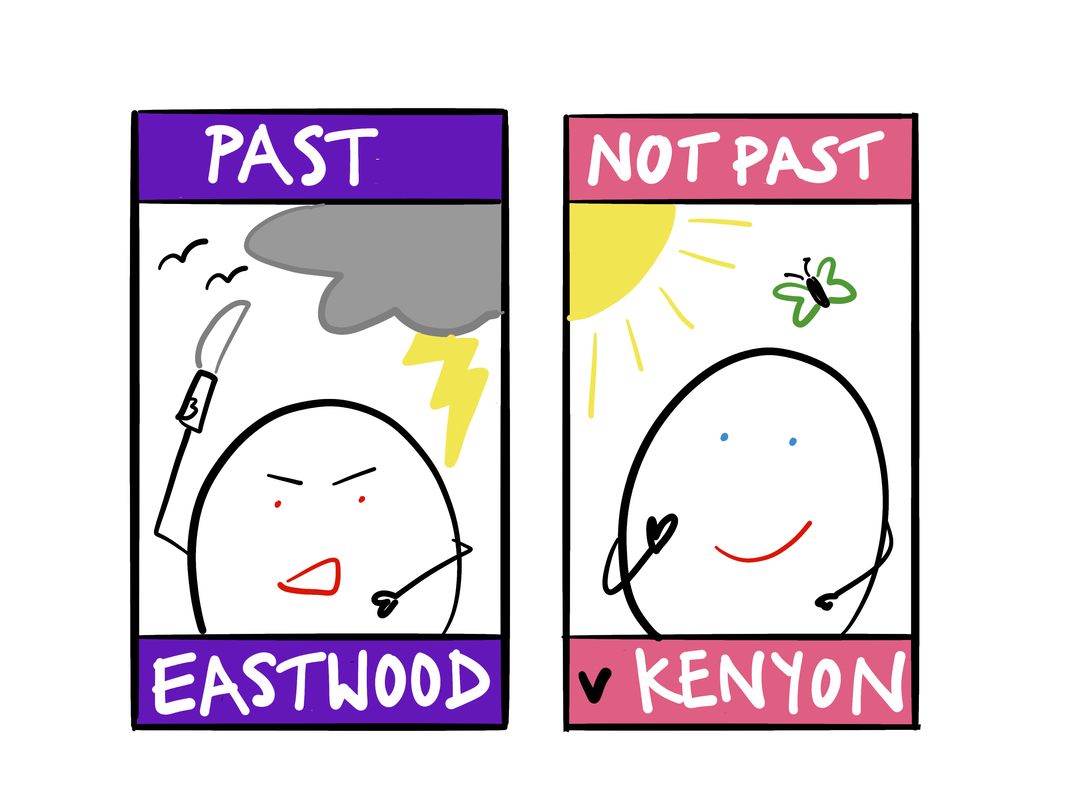

CONSIDERATION MUST NOT BE PAST

Past consideration is not good consideration. Consideration given in the past, i.e. not in reaction to, but before a promise from the other party, will not be valid ((Eastwood v Kenyon (1840) (HC)).

Eastwood was appointed as the executor of an estate and also became full guardian of the deceased’s only surviving daughter. He spent a lot of his own money on her maintenance and education, and also spent his own money on the property of the deceased which would later be for the benefit of the daughter when she came of age. Eastwood borrowed some money to do this. The daughter later married Kenyon who promised to repay Eastwood what he had borrowed to bring up the girl. However, because Eastwood had borrowed the money and brought up the girl before Kenyon made the promise there was no binding contract and Kenyon did not have to pay the money.

You can also use the case of Roscorla v Thomas (1842) (HC). After Roscorla purchased a horse from Thomas, Thomas assured Roscorla that the horse was sound and free from vice. This turned out not to be true but Roscorla was unsuccessful in his claim for breach of promise because the consideration that he had given for the horse was in the past and not good consideration for the subsequent promise made by Thomas.

EXCEPTION TO PAST CONSIDERATION IS NOT GOOD CONSIDERATION

If there was a prior understanding between the parties then consideration in the past will be valid (Lampleigh v Brathwait (1615)).

Brathwait was condemned to death for murdering a man. He asked Lampleigh to do everything he could to get a pardon from the King. Lampleigh succeeded but was left out of pocket. When he was released Brathwait offered to give him £100 in thanks but never did. In court Brathwait argued that the consideration for this promise was past and therefore bad consideration. The court held that because Lampleigh had carried out Brathwait’s specific request, and there had been a prior understanding between them, the past consideration was valid.

This also arises in commercial contexts (Re Casey’s Patents (1892) (HC)). Casey managed some patents for a company, After he had finished the work they promised him one third of the patents but then changed their minds. They argued that Casey’s consideration was invalid because it was past. The court held that there had been an implied understanding between the parties at the time that Casey would receive something in return for his work and therefore the consideration was good.

This principle was set out in the more modern case of Pao On v Lau Yin Long (1980) (PC). ‘An act done before the giving of a promise to make a payment can sometimes be consideration for the promise. The act must have been done at the promisor’s request, the parties must have understood that the act was to be remunerated either by payment or conferment of some other benefit’, Lord Scarman.

CHECK OUT OUR SHOP FOR LAW FLASHCARDS | MIND MAPS | MUGS

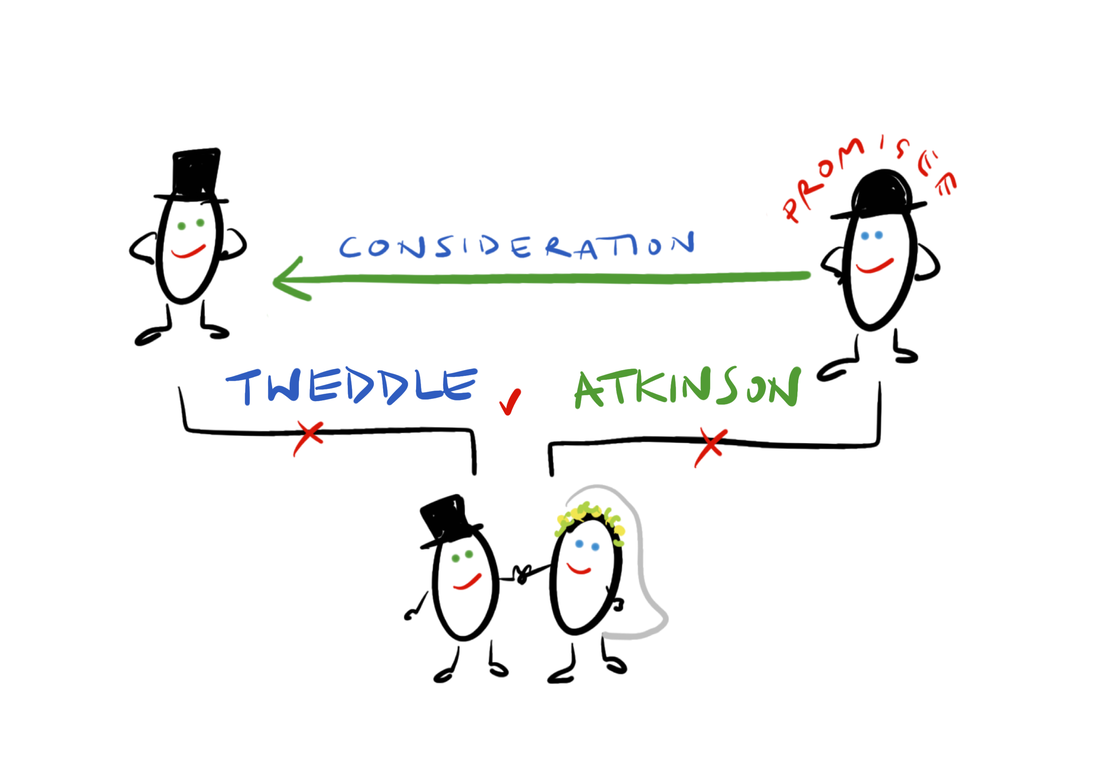

CONSIDERATION MUST MOVE FROM THE PROMISEE

Only the promisee (the person who has been promised something) can enforce the contract because they have provided consideration for the promise (Tweddle v Atkinson (1861) (Court of Queen’s Bench)).

The father-of-the-bride and the father-of-the-groom contracted with each other to both make a payment to the groom. The father-of-the-bride died before paying. The father-of-the-groom then also died. The groom was unable to enforce the contract and get the money from the father-of-the-bride’s estate because he was not the promisee and had provided no consideration. Only the groom’s father could have enforced the contract but he was dead. (This is also dealt with in Privity of Contract).

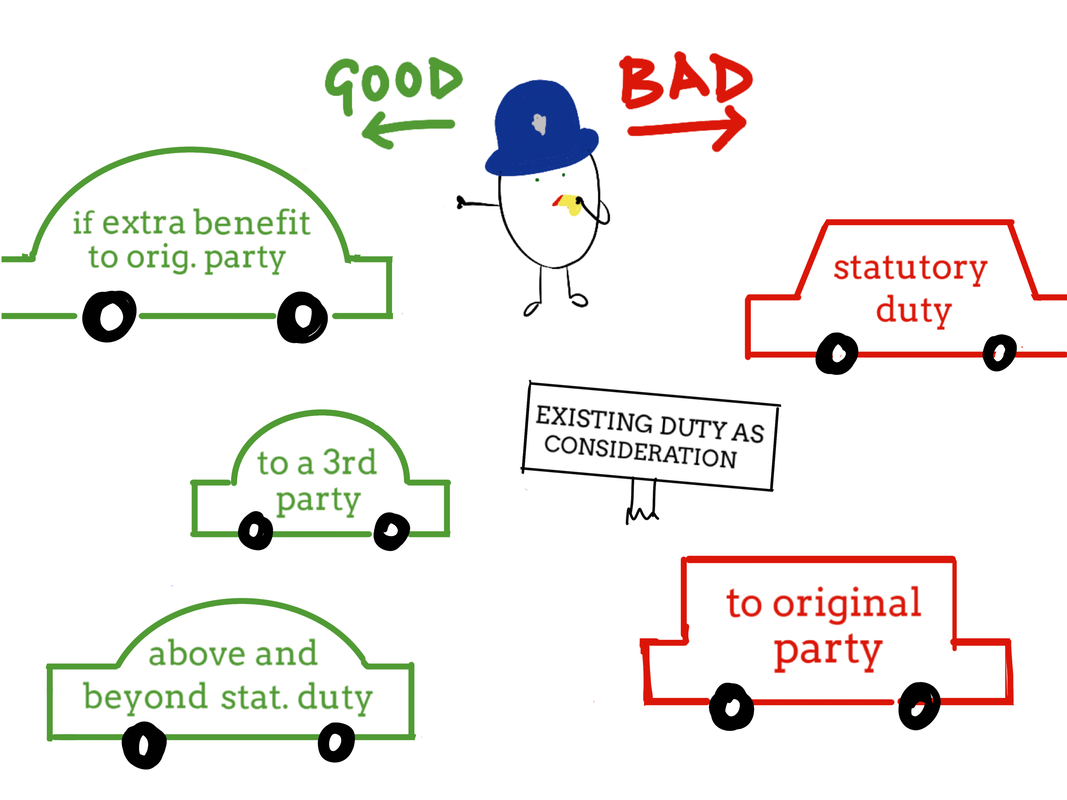

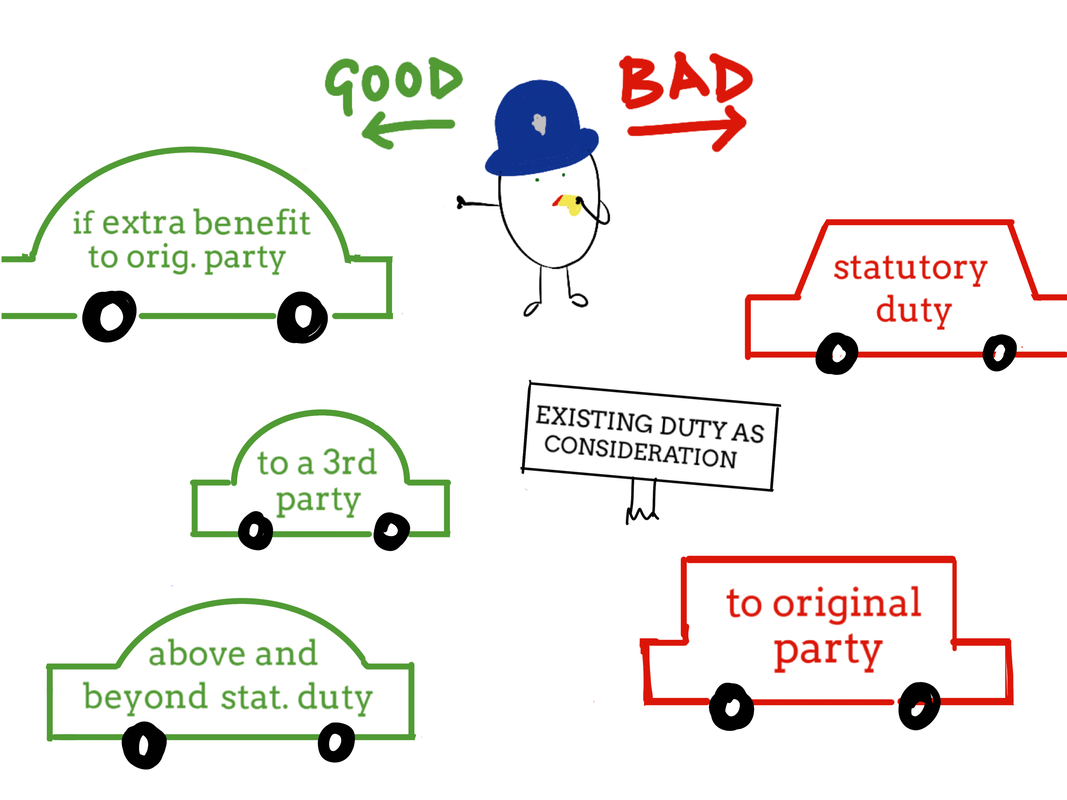

EXISTING DUTIES AS CONSIDERATION

Some exiting duties are bad consideration and some are good…

EXISTING DUTY TO THE ORIGINAL PARTY

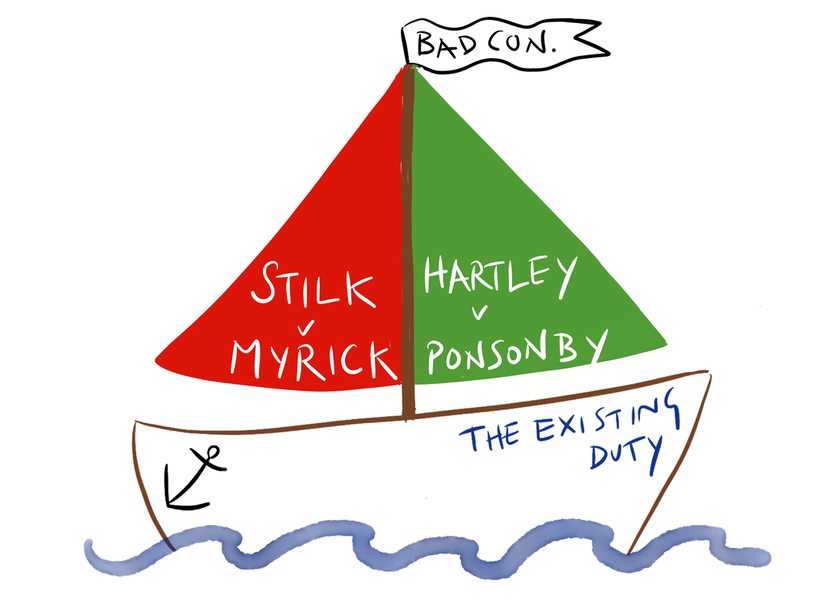

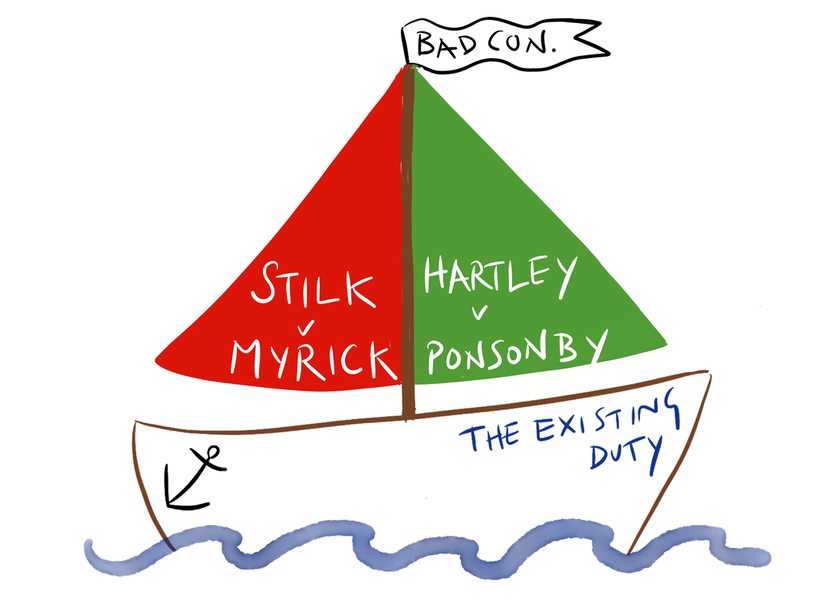

In general an existing duty to the original party is not good consideration for any further promise. Compare the two cases of Stilk v Myrick (1809) (Assizes) and Hartley v Ponsonby (1857) (HC).

| In Stilk v Myrick (1809) (HC) two people had deserted from a ship. The captain offered to share their wages between the rest of the crew if they did the work of the deserters on the return voyage. However, their contracts already stated that they were obliged to do any work necessary to get the ship home. Therefore the captain, despite his promise, was not obliged to pay them any extra wages because they had not gone beyond their existing duty. |

In Hartley v Ponsonby (1857) (HC) most of the crew had deserted and the captain offered the remaining men extra money to sail the boat home. Because of the severe reduction in the crew the remaining men went beyond their existing duty by taking on a much more difficult and dangerous journey. Therefore, they were entitled to the extra pay. |

Read more in-depth details and analysis of Stilk v Myrick and Hartley v Ponsonby here.

EXCEPTION TO EXISTING DUTY IS NOT GOOD CONSIDERATION

However, more recently the courts have held that an existing duty can be good consideration if the other party gains a practical benefit or obviates a disbenefit from the completion of the existing duty (Williams v Roffey (1991) (CoA)).

Williams had been commissioned to refurbish a block of flats. In the agreement between Williams and the property owners there was a penalty clause for late completion (meaning that Williams would have to pay an amount if he didn’t complete the work on time). Williams subcontracted Roffey to do some carpentry work like installing windows within the block of flats. When it became apparent that Roffey was running behind schedule on the carpentry work, Williams offered Roffey additional money to speed up and finish his existing work obligations on time. Later, when the job had been finished on time, Roffey claimed this additional payment from Williams. Williams refused to pay on the grounds that Roffey had provided no extra consideration. Completing the work on time was part of the initial promise, nothing more was given for additional payment. However, the court held that a ‘practical benefit’ had been gained by Williams (not having to pay the penalty for missing the deadline) so Roffey was entitled to the extra payment.

The principle that flows from this case can be summarised as the following. Performing an existing contractual duty can be good consideration if:-

- A has a contract to employ B for work,

- Before the work is done A has reason to believe that B will not completely perform their contractual obligations on time,

- A offers B more money to do so,

- From this A will obtain a practical benefit or obviate a disbenefit,

- There is no fraud or economic duress.

|

Read more about the effect of Williams v Roffey on Stilk v Myrick here.

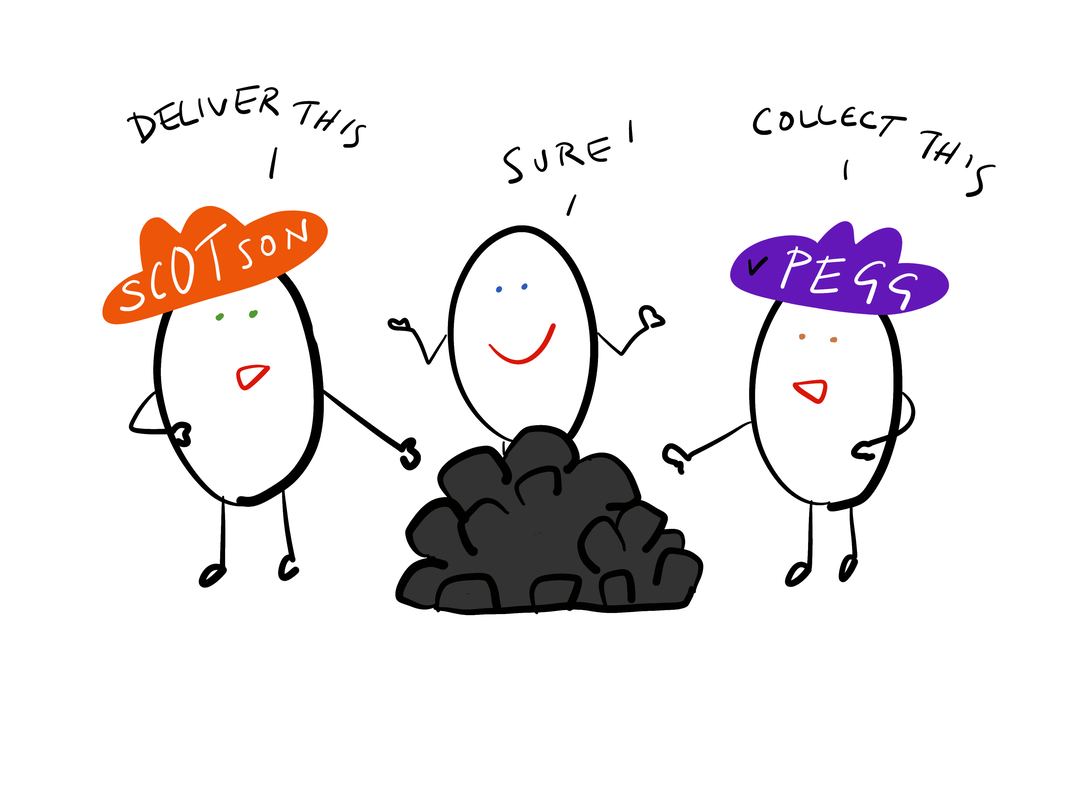

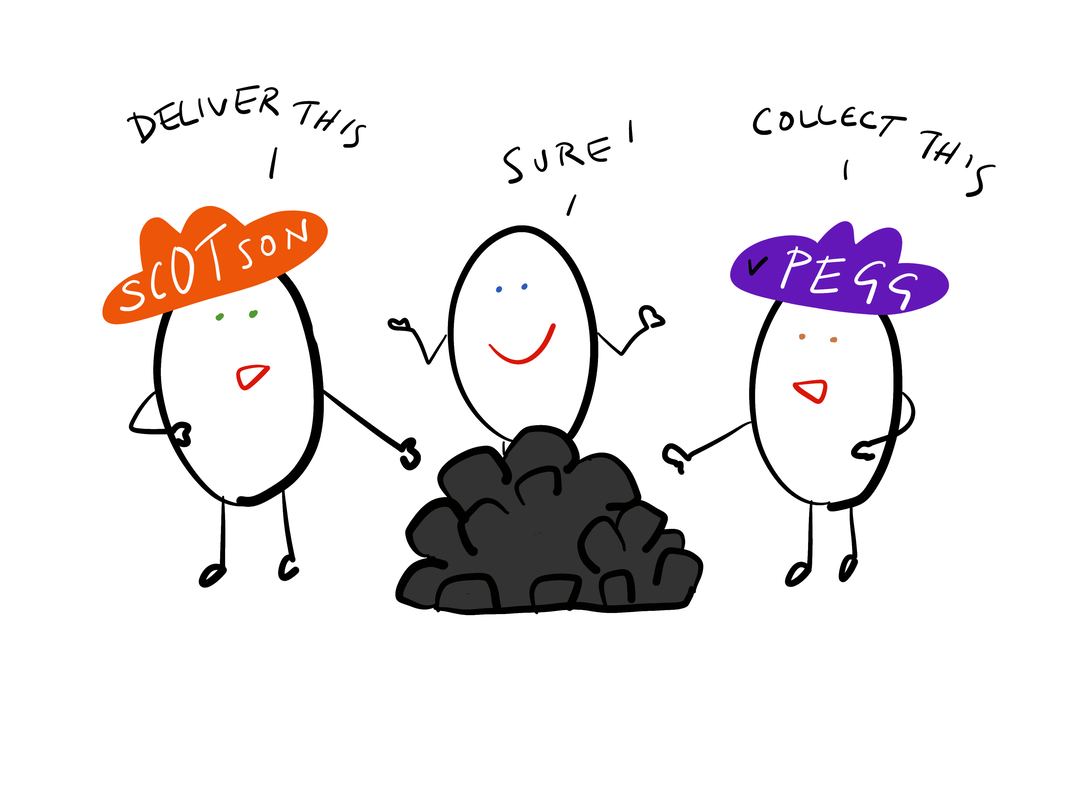

EXISTING DUTY TO A THIRD PARTY

Performance of an existing contractual duty with one party can be good consideration in a contract with another party. In other words, a party can perform one duty which is valid consideration for two different contracts (Scotson v Pegg (1861) (Court of Exchequer)).

In this case, both Scotson and another party had paid Pegg to perform the same duty (to unload and deliver coal from a ship). Scotson argued that Pegg was not providing consideration for two separate contracts and should not be paid twice but the court disagreed.

The principle was explained in New Zealand Shipping Co Ltd v AM Satterthwaite & Co Ltd (The Eurymedon) (1975) (PC of New Zealand); the party performing the one promise for two parties is under double the contractual liability, or risk, and this is considered sufficient consideration. In this case a carrier company had entered into a contract with Satterthwaite to transport a drilling machine by sea from England to New Zealand. In the contract for carriage there was a clause limiting the carrier’s liability. The clause also stated that such limitation of liability applied to servants, agents and any independent contractors (often referred to as a ‘Himalaya clause’). The carrier company hired some stevedores (persons employed to load and unload ships). The stevedores damaged the drill and argued that the limitation of liability clause also applied to them despite having no contractual relationship with Satterthwaite. The court held that the stevedores’ obligation to unload the ship was good consideration to benefit from the protection of the limitation clause.

STATUTORY DUTY AS CONSIDERATION

In general the performance of an existing statutory duty does not amount to good consideration because the party is under a legal duty to perform regardless of their contractual obligations (Collins v Godefroy (1831) (HC)).

Collins received a subpoena that required him to be an expert witness in court. Godefroy promised to pay Collins for his attendance but this was not enforceable because Collins had a statutory duty to attend.

A legal duty could also include a duty of care in Tort law or a fiduciary duty in Equity.

EXCEPTION

Performance of duties above and beyond a statutory duty can be good consideration (Ward v Byham (1956) (CoA)).

An unmarried couple had a child. When they split up the father offered the mother £1 per week in maintenance to bring up the child and she agreed to ensure that the child was ‘well looked after and happy’. When she remarried the father stopped the payments on the grounds that she was only fulfilling her statutory duty towards the child which was not good consideration. However, the court held that ensuring a child is well looked after and happy goes beyond any statutory duty and she was therefore entitled to the £1 per week.

Also see Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan County Council (1925) (HoL) in which the court found that a local police force had performed a service beyond their public duty when protecting a mine during a strike. The mine owner argued that it was part of their duty to prevent crime and protect the public but the court agreed with the police that their public duty was to provide policing as deemed necessary by the police. Anything beyond this was good consideration. These situations are now governed by the Police Act 1996.

FORBEARANCE TO SUE

A promise not to enforce a good claim is valid consideration. In Wade v Simeon (1846) the court held that forbearing where the claim is known to be invalid is not good consideration.

What if the claimant thinks its claim is good but they actually have no claim in law?

In Cook v Wright (1861) the claimants honestly believed that the defendant owed them money and was under a statutory duty to do so. The defendant denied this but eventually promised to pay a reduced amount after being threatened with litigation. Later, the defendant discovered that he was under no legal obligation to pay the claimants. He said that his promise to pay the reduced amount was not supported by any consideration. However, the court held that he was liable and that the consideration given was that he would not be sued. The defendant had been saved the hassle of having to defend the claim, even if the claimants would have lost.