JUMP TO: FALSE – Avon Insurance v Swire Fraser | McInerny v Lloyds Bank – STATEMENT OF FACT – Edgington v Fitzmaurice | Wales v Wadham | Bisset v Wilkinson | Smith v Land House Property | Esso Petroleum v Mardon | Pankhania v Hackney LBC – MAKING A STATEMENT – Spice Girls v Aprilia World Service | Gordon v Selico | Keates v Earl of Cadogan | Dimmock v Hallett | With v O’Flanagan | Lambert v Co-operative Insurance Society | Tate v Williamson | Gordon v Gordon – INDUCEMENT – Smith v Chadwick | Museprime Properties v Adhill Properties | Peek v Gurney | Horsfall v Thomas | Attwood v Small | Redgrave v Hurd | Smith v Eric Bush | Peekay Intermark Ltd v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group

REVISE | TEST

MISREPRESENTATION

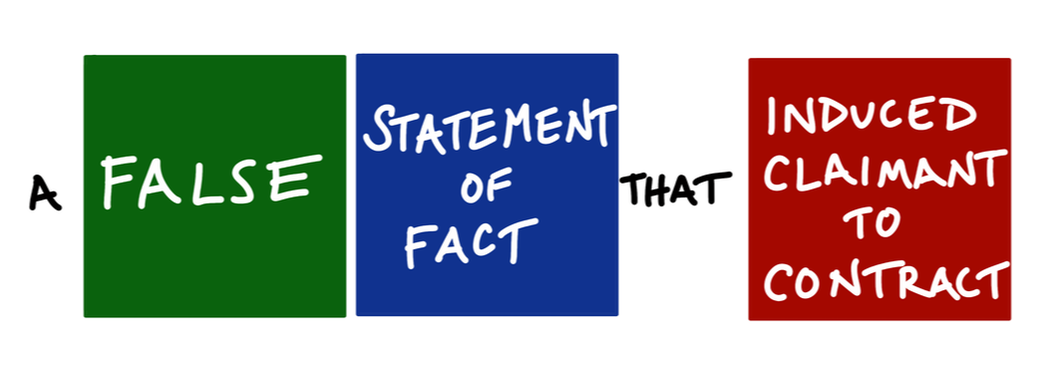

If any of the statements made before the contract is formed are found to be false then the representee (the person the statement was made to) may have a claim for misrepresentation. This is true whether the statement was only a mere statement or incorporated into the contract as a term (see Terms and Exemption Clauses).

The effect of a misrepresentation is, in general, to make the contract voidable.

In order to be a misrepresentation a statement must be…

FALSE

A statement will not be false if it is ‘substantially correct’ and the difference between the statement and the truth did not induce the representee to enter into the contract (Avon Insurance v Swire Fraser Ltd (2000) (HC)).

Presentation documents produced by Swire Fraser stated that each individual insurance claim would be assessed by their lead underwriter. In fact they were assessed by individuals being overseen by the lead underwriter. The statement was deemed to be substantially true and not important enough in the claimant’s decision to agree to the contract to be a misrepresentation.

A statement must also be unambiguous. If the representee puts an unreasonable construction on it that the representor did not intend then it cannot be a misrepresentation (McInerny v Lloyds Bank (1974) (CoA)).

STATEMENT OF FACT

The statement must be a fact and not a statement of future intention or opinion. A statement of law can be a statement of fact.

FACT NOT FUTURE INTENTION

A statement of future intention cannot be a misrepresentation because the representor might change their mind or be unable to fulfil the intention. However, if it can be shown that they never in fact intended to fulfil the statement it can be a misrepresentation (Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) (CoA)).

Edgington bought debenture bonds from a company that had claimed in its prospectus that the money raised would be spent on new buildings, vans, horses and expanding the business into selling fish. This was a statement of future intention but as it could be proved that the company never intended to spend the money on these things, but instead on paying off debts, it was found to be a misrepresentation.

Compare this to Wales v Wadham (1977) in which a divorce settlement was based on the wife’s statement that she would never remarry. When she did remarry the ex-husband tried to rescind the agreement. However, as at the time the statement was made the wife had meant what she said her statement was deemed to be one of future intention and not a misrepresentation.

FACT NOT OPINION

Statements of opinion are not generally statements of fact (Bisset v Wilkinson (1927) (PC New Zealand)).

During negotiations for the purchase of farm land Bisset told Wilkinson that he thought the land could hold 2,000 sheep. Bisset had never used the land to farm sheep and Wilkinson knew this. When Wilkinson bought the land he found that it was almost impossible to sustain this many sheep on the land. The statement was taken as one of opinion and not fact because of the relative levels of knowledge of each party (fairly even as neither had ever farmed sheep on the land) and the fact that Wilkinson had not proved definitively that 2,000 sheep were unsustainable.

EXCEPTION

However, if the representor has specific knowledge that puts them in a better position to know the truth than the representee their statement will be taken as one of fact and not opinion (Smith v Land House Property Corporation (1884) (CoA)).

Smith bought a hotel from Land & House Property Corp who had described one of the tenants as ‘most desirable’. In fact, the tenant had been made bankrupt and owed money to the hotel. In general, the desirability of a tenant is an opinion but, in this case, because the defendants were in a position to know more about the situation than the claimant, it was considered a statement of fact.

Bowen LJ said that the statement ‘amounts at least to an assertion that nothing has occurred in the relations between the landlords and the tenant which can be considered to make the tenant an unsatisfactory one. That is an assertion of a specific fact.’

Also see Esso Petroleum v Mardon (1976) (CoA) in which an Esso representative’s estimate as to a petrol station’s gallon per year sales was a statement of fact because they had many years experience and substantial skill in that area.

STATEMENTS OF LAW

If someone makes a false statement about a law, i.e. stating the law incorrectly, it cannot be the basis of a claim for misrepresentation. However, if a false statement is made about the effect of a law this can be the basis for a misrepresentation claim (Pankhania v Hackney LBC (2002) (HC)).

Pankhania bought a carpark from Hackney LBC having been told that it was let out to a tenant whose contract could be ended with 3 months’ notice. However, it was actually a protected tenancy under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. This was a misrepresentation because the council misrepresented the effect of the law rather than the law itself.

MAKING A STATEMENT

A statement can be made in words or by conduct (Spice Girls v Aprilia World Service (2002) (CoA)).

Aprilia had agreed to sponsor the Spice Girls’ next tour. Before the agreement had been finalised the group was photographed for promotional material. At the time the group knew that Geri Halliwell had decided to leave before Aprilia’s sponsorship deal ended. Her appearance at the photo shoot was a misrepresentation by conduct.

Also see Gordon v Selico (1986) (CoA) in which the defendant painted over dry rot to conceal it from prospective tenants. This was also misrepresentation by conduct.

SILENCE AS A STATEMENT

Silence cannot be a statement. There is no legal obligation to disclose facts even if those facts might persuade the other party not to enter into the contract (Keates v Earl of Cadogan (1851) (Court of Common Pleas)).

As Keates had never asked, the Earl of Cadogan had never told him that the house he was going to rent was uninhabitable. As long as the Earl had not done anything to make Keates think that it was habitable there had been no misrepresentation.

There are several exceptions to this exception!

HALF TRUTHS

If a statement is technically true but in reality misleading, this form of silence on the truth of the matter will be a misrepresentation (Dimmock v Hallett (1866) (CoA)).

Dimmock bought some land at auction that had been advertised as having tenants. This was a misrepresentation because although it was true it was misleading. The tenants had handed in their notice to leave and the seller had been silent on this matter.

CHANGE OF CIRCUMSTANCES

If a statement was made but a change of circumstances means that it is no longer true then there is an obligation not to remain silent but to correct the statement (With v O’Flanagan (1936) (CoA)).

O’Flanagan was selling his medical practice and gave With a figure for the practice’s income. However, between this and the sale O’Flanagan became ill, his patient numbers dropped and the income with it. By not telling With about the change of circumstances his statement had become a misrepresentation. The court held that it was the duty of the seller to communicate the change of circumstances to the purchasers.

CONTRACTS UBERRIMAE FIDEI

Certain contractual relationships are uberrimae fidei – of the utmost good faith – and bring with them a legal duty to disclose all material facts.

- Insurance contracts – In Lambert v Co-operative Insurance Society (1975) (HC) Lambert’s non-disclosure of her husband’s recent conviction for conspiracy to steal was a misrepresentation.

- Confidential relationships; solicitor and client, business partners, trustee and beneficiary, etc. In Tate v Williamson (1866) (HoL) Williamson was asked to provide financial advice to a young man with a lot of student debt. Williamson advised him to sell his land to repay his debts. Williamson bought the land at half its market value based on material facts that he knew and did not disclose to the young man. Non-disclosure of the true value of the property was a misrepresentation. As a financial adviser, Williams was in a fiduciary relationship with the young man.

- Facts concerning the land title in a sale of land contract.

- Family arrangements for the distribution of family property (Gordon v Gordon (1817) (HC)).

|

INDUCEMENT

The statement must have induced the claimant to enter into the contract. A claimant does not have to show that the false statement was the only reason they entered into the contract, so long as it was a material one (Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) (CoA)).

WAS THE STATEMENT MATERIAL?

This is an objective test based on what would have influenced the reasonable man. If the statement is found to have been material to the claimant then inducement into the contract will be inferred (Smith v Chadwick (1884) (HoL)).

Chadwick produced a brochure for a company which claimed that one of the Directors was a Member of Parliament. Smith invested in the company but lost money and claimed misrepresentation. It was found that, although it was false and the MP was not a Director, Smith did not know who the MP was and this had not been material in his decision to invest. Also see Avon Insurance v Swire Fraser (2000) (HC) above.

In addition, a statement cannot have induced a party if they already knew it to be false.

If the objective test fails then the claimant must subjectively prove that they were induced into the contract by the false statement, it will not be automatically inferred (Museprime Properties v Adhill Properties (1990) (HC)).

DID THE REPRESENTOR INTEND THE CLAIMANT TO RELY ON THE STATEMENT?

Similarly, if the representor did not intend the representee to rely on the statement it cannot have induced them into the contract (Peek v Gurney (1873) (HoL)).

A company prospectus specifically aimed at new shareholders made false statements about the company. Peek later bought his shares on the open market and lost a lot of money. He made a claim against Gurney based on the false prospectus but it was not a misrepresentation because it had not been designed with the intention that subsequent buyers would rely on it, only initial shareholders. The court found that the directors only had a responsibility to the first purchaser of the shares, not to those who later bought the shares from the original purchasers.

DID THE REPRESENTEE KNOW OF THE STATEMENT?

In order to have relied upon the statement the representee must have known about it (Horsfall v Thomas (1862)(Court of Exchequer)).

Horsfall was paid to make a gun for Thomas. He delivered the gun but tried to hide a defect by inserting a metal plug into the gun. Thomas paid for the gun without inspecting. Because he was not aware of Horsfall’s conduct it could not have induced him to enter into the contract.

Contrast this with Gordon v Selico (1986) (CoA) (above) in which the tenants did inspect the house but could not have noticed the dry rot because it had been concealed by the defendants.

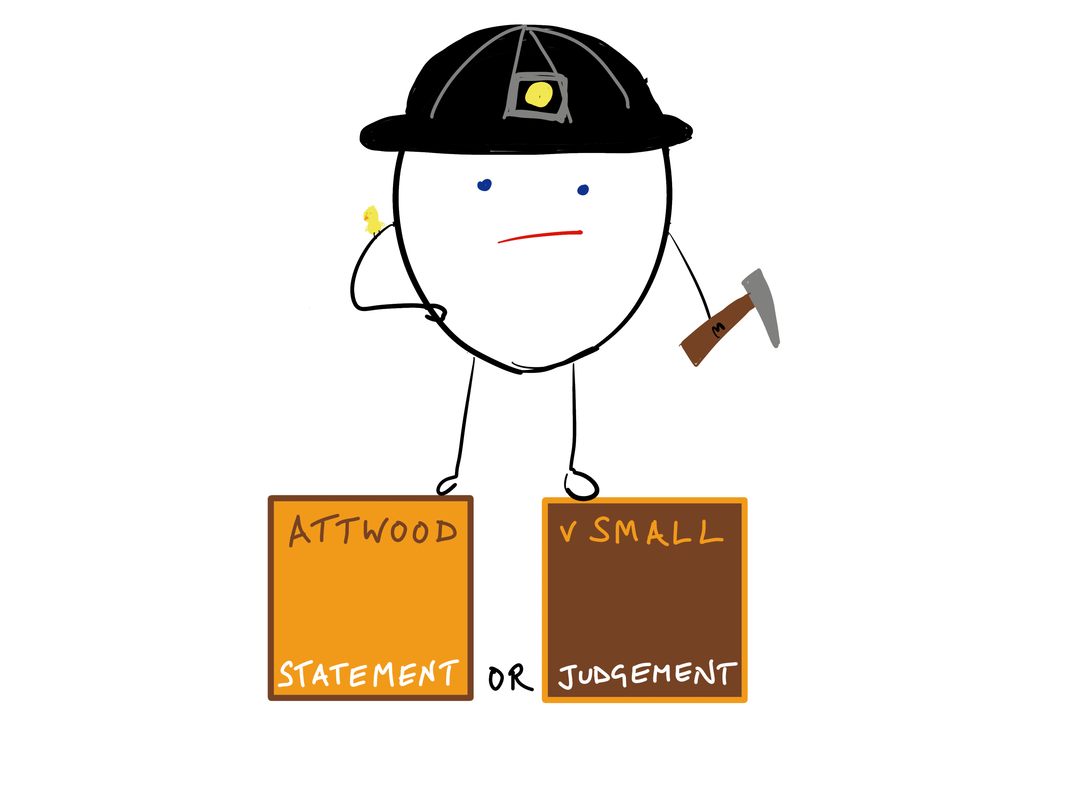

DID THE REPRESENTEE RELY UPON THEIR OWN JUDGMENT OR THE STATEMENT?

If the representee made their own efforts to validate the statements then it could be argued that they relied upon their own judgment and information rather than the statement made by the representor (Attwood v Small (1838) (HoL)).

Not believing the statements made by Small, the seller of a mine, Attwood employed an agent to create a private report. This also stated that the mine was a good purchase. This turned out not to be true but the court decided that Attwood had solely relied upon the private report and therefore any false statement in Small’s reports had not induced him to buy the mine.

However, this does not apply if the statement was a fraudulent misrepresentation or the representee can prove that they relied partly on the misrepresentation and partly on their own investigation.

IS THE REPRESENTEE OBLIGED TO CHECK THE STATEMENT?

A claimant will not be stopped from claiming misrepresentation if they had the chance to double check the statement but did not (Redgrave v Hurd (1881) (CoA)).

Redgrave was selling his house and solicitors practice. He made a false statement about the annual income in the documents but offered Hurd the chance to inspect the papers which would have shown him that the statement was false. Hurd declined the offer. The court found that this did not restrict him from successfully claiming for misrepresentation as he had still relied upon the statement.

However, there may be a distinction based on whether it was reasonable or not for the claimant to have checked the statement. For example, in Smith v Eric Bush (1990) (HoL) it was unreasonable for a commercial party who had knowledge and resources available not to have checked the statement.

MUST IT BE REASONABLE FOR THE REPRESENTEE TO HAVE RELIED UPON THE STATEMENT?

If the representee relied upon the statement then they do not have to prove that it was reasonable to do so. This will go towards proof; the more unreasonable it was to rely upon it the harder it will be to prove that they did so (Museprime Properties Ltd v Adhill Properties Ltd (1990) (HC)).

If a false statement is made but then corrected in any subsequent signed contract the representee will not be able to claim that the statement was a misrepresentation (Peekay Intermark Ltd v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (2006) (CoA)). In this case, the true position appeared clearly on the face of the documents containing the terms of the contract, therefore the claimant could not be said to be induced by a former representation.