JUMP TO: PRIMARY VICTIMS | SECONDARY VICTIMS | RESCUERS | BYSTANDERS | REVISE | TEST

NERVOUS SHOCK

Nervous shock and psychiatric harm mean any mental or psychological injury sustained by a claimant. If a claimant has suffered physical and psychiatric injury their claim will be assessed as it would be for physical harm. If they have suffered only psychiatric harm then the case will be dealt with using the mechanisms described below.

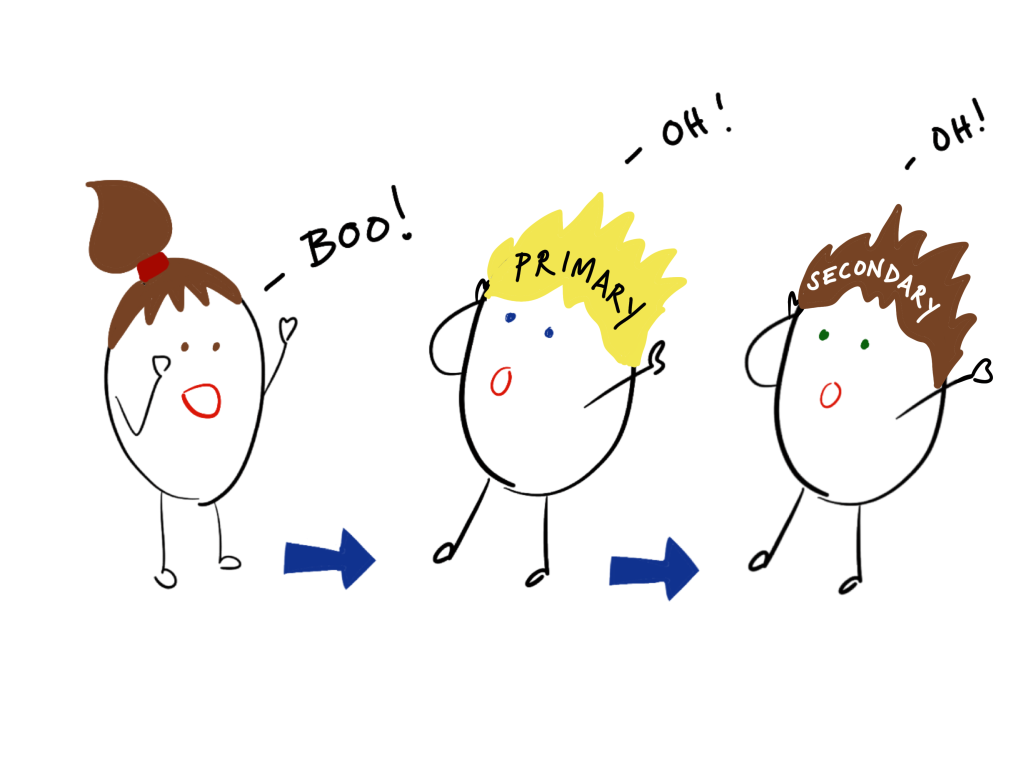

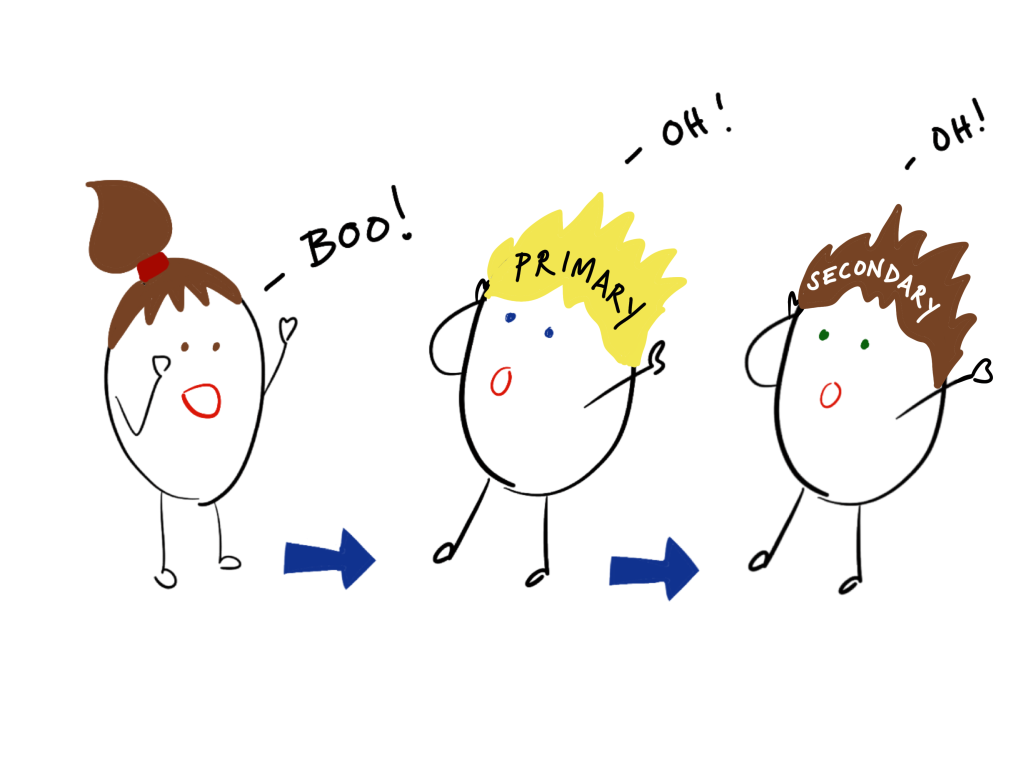

The court will begin by deciding whether the claimant is a primary or secondary victim. The rules for establishing a duty of care are different for each.

PRIMARY VICTIMS

A claimant will be a primary victim if they suffered psychiatric damage as a result of reasonable fear for their own physical safety. This means that the claimant was involved, or feared that they might be involved, in the negligent event. They must have been in the zone of physical danger.

For example, in Dulieu v White (1901) (HC) a barmaid suffered nervous shock and a miscarriage when a carriage crashed through the wall of the pub she was working in. Fear for her physical safety had caused her nervous shock so she was able to recover as a primary victim.

In Rothwell v Chemical & Insulating Co (2007) (HoL) the claimant had inhaled asbestos particles during his work for the defendant. He had not suffered any physical damage but was so worried that he might in the future that he became severely depressed. His illness had not been brought on by an event that had happened but by the fear of something in the future so he could not be classed as a primary victim.

DUTY OF CARE

For a primary victim the standard mechanisms for establishing a duty of care are used. (See General Duty of Care section).

LOSS IS FORESEEABLE

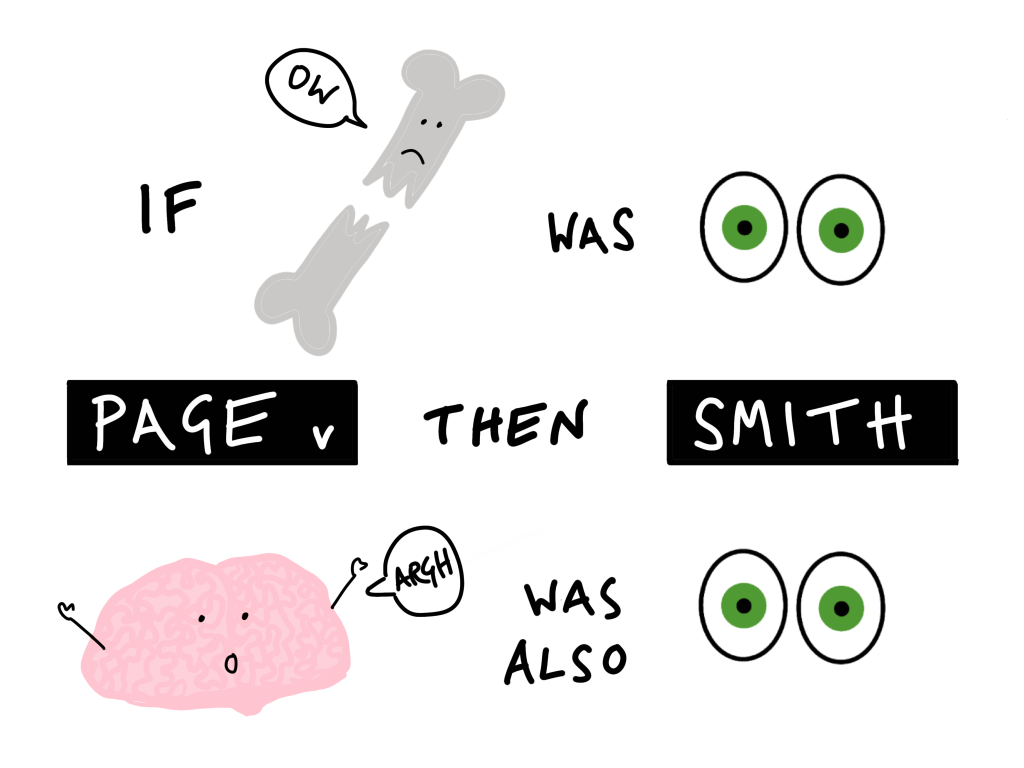

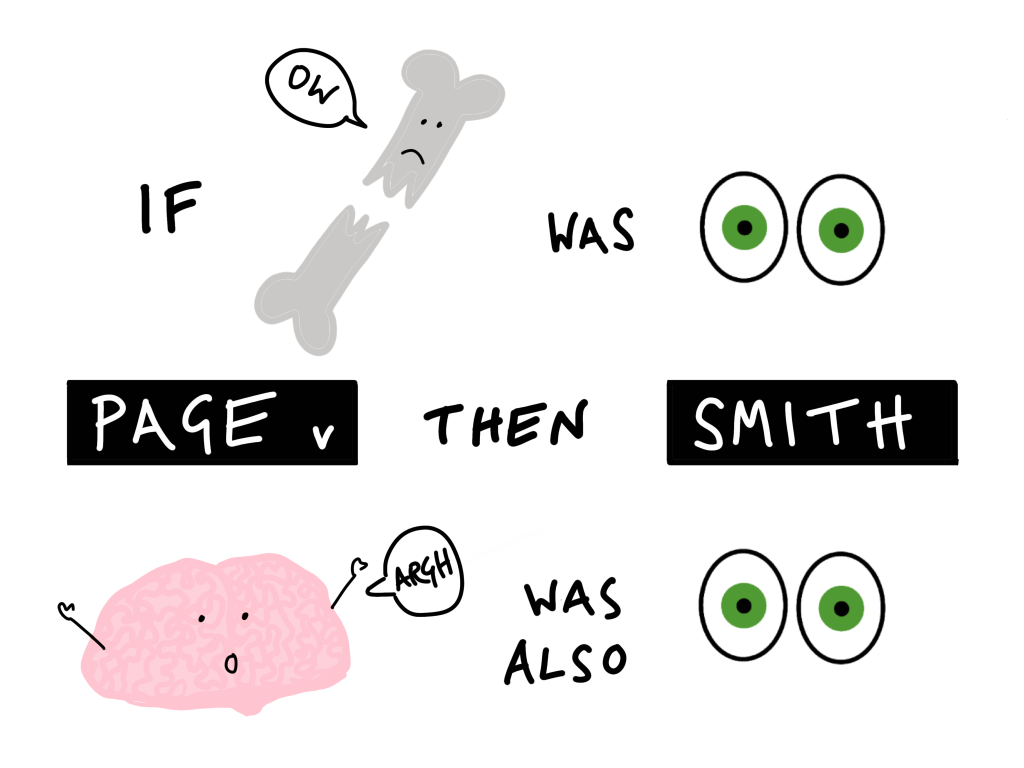

If the physical harm suffered was foreseeable then any psychiatric harm suffered is also automatically foreseeable. The main case in this area is Page v Smith (1996) (HoL).

Page had been involved in a car accident caused by the negligence of the defendant. He had suffered no physical injury but the nervous shock of the accident caused his ME (classed as a psychiatric disorder at the time) to worsen. The defendant argued that he was not liable for the harm because it was not foreseeable that his negligent driving would cause or worsen ME. The court disagreed and held that when physical harm is reasonably foreseeable any psychiatric harm is also automatically foreseeable. It does not matter if a person of ordinary fortitude would not have suffered that harm.

MEDICALLY RECOGNISED ILLNESS

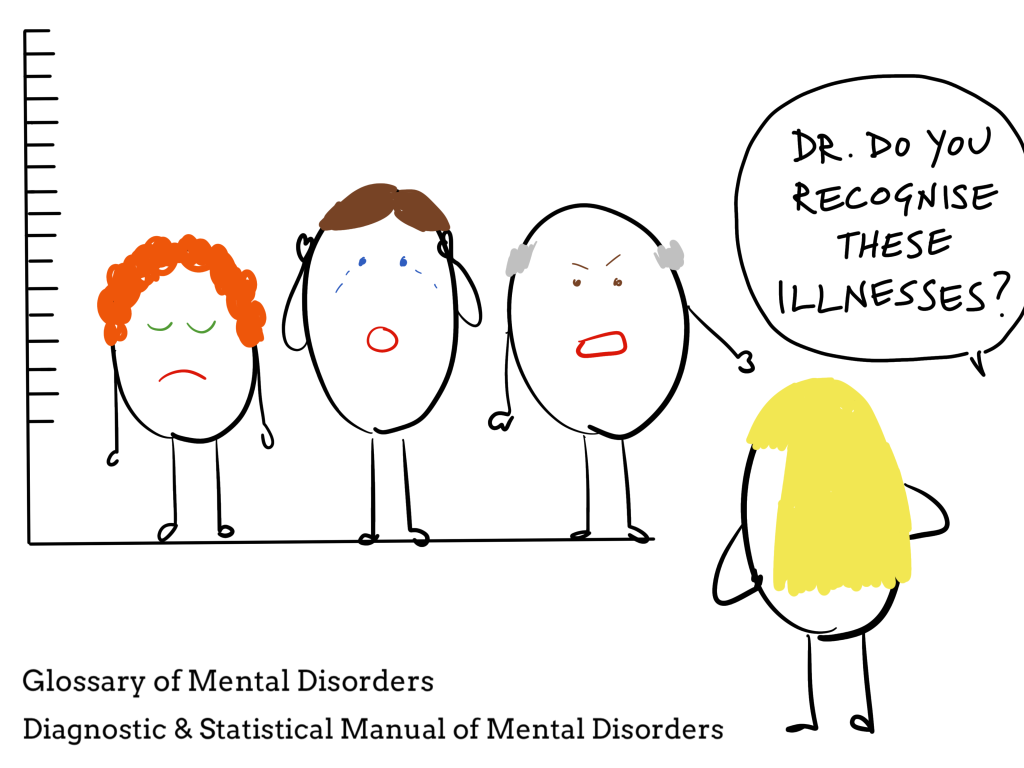

However, the claimant must prove that their harm is a medically recognised form of psychiatric illness.

Courts will refer to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association and the Glossary of Mental Disorders in the International Classification of Diseases. These definitions are updated and change over time to include newly recognised forms of mental illness so what was not compensated for in an old case may be in a later one.

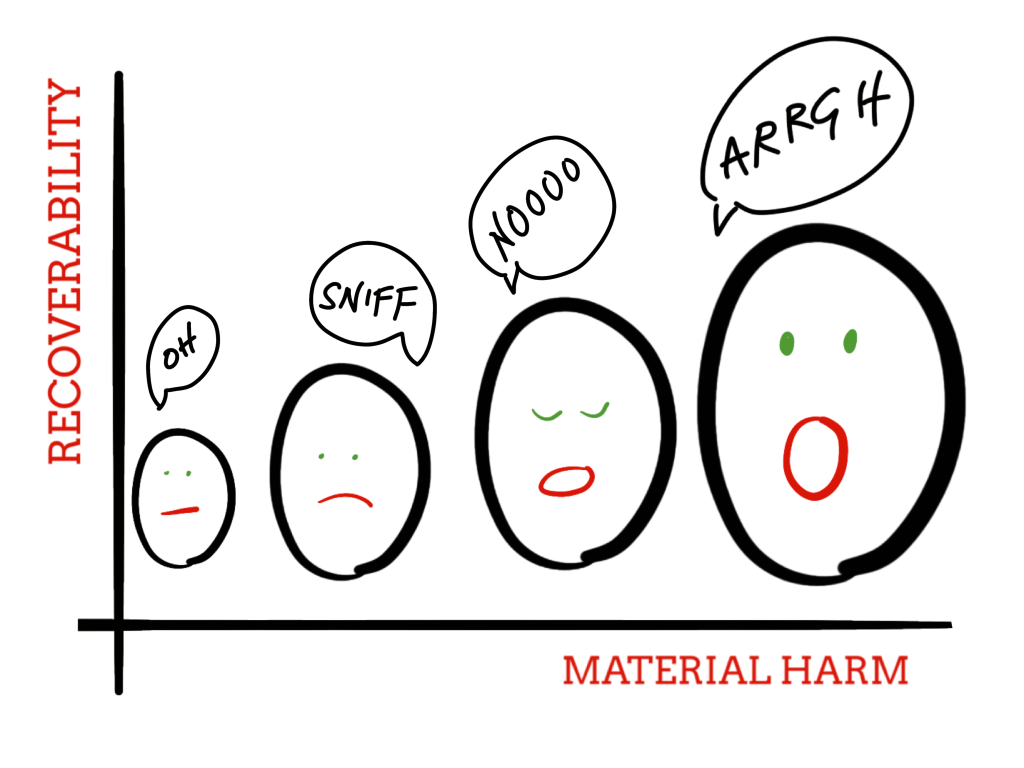

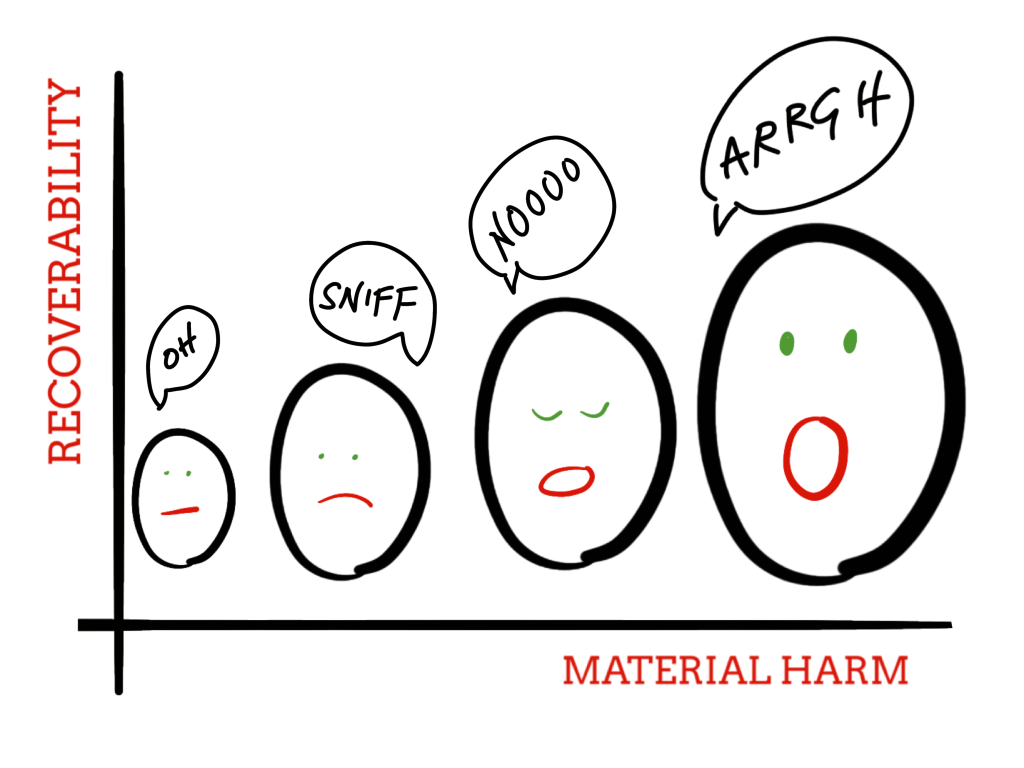

IS HARM MATERIAL?

The harm must be ‘material’; for example the courts will not allow recovery for fear, distress or mental grief, or what they consider to be an ordinary reaction to an unpleasant situation.

In Reilly v Merseyside HA (1995) (CoA) a couple who were trapped in a lift for over an hour were not successful in their claim because their suffering did not go beyond the fear that anyone would have experienced, it did not induce a medically recognised psychiatric illness.

SECONDARY VICTIMS

A secondary victim suffers nervous shock due to fear for the safety of another. Usually this would be witnessing harm done to another person.

For example in Hambrook v Stokes (1925) (CoA) a mother who witnessed a runaway lorry heading towards her children was classed as a secondary victim. Also Mrs Hinz who witnessed her husband die and children injured in a car accident was a secondary victim (Hinz v Berry (1970) (CoA)).

Who could be classified as a secondary victim was extended in McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983) (HoL) to those who had not necessarily witnessed the initial event.

A mother who was not at the scene of the accident but suffered nervous shock seeing her family in hospital in the immediate aftermath of a car accident was able to claim as a secondary victim.

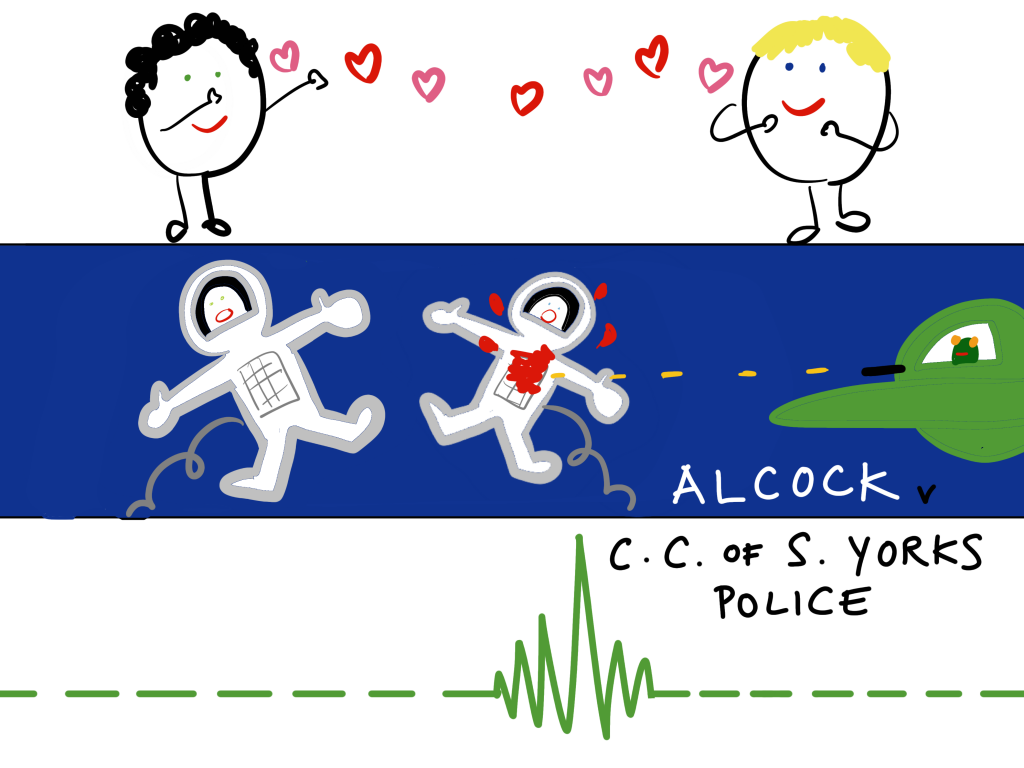

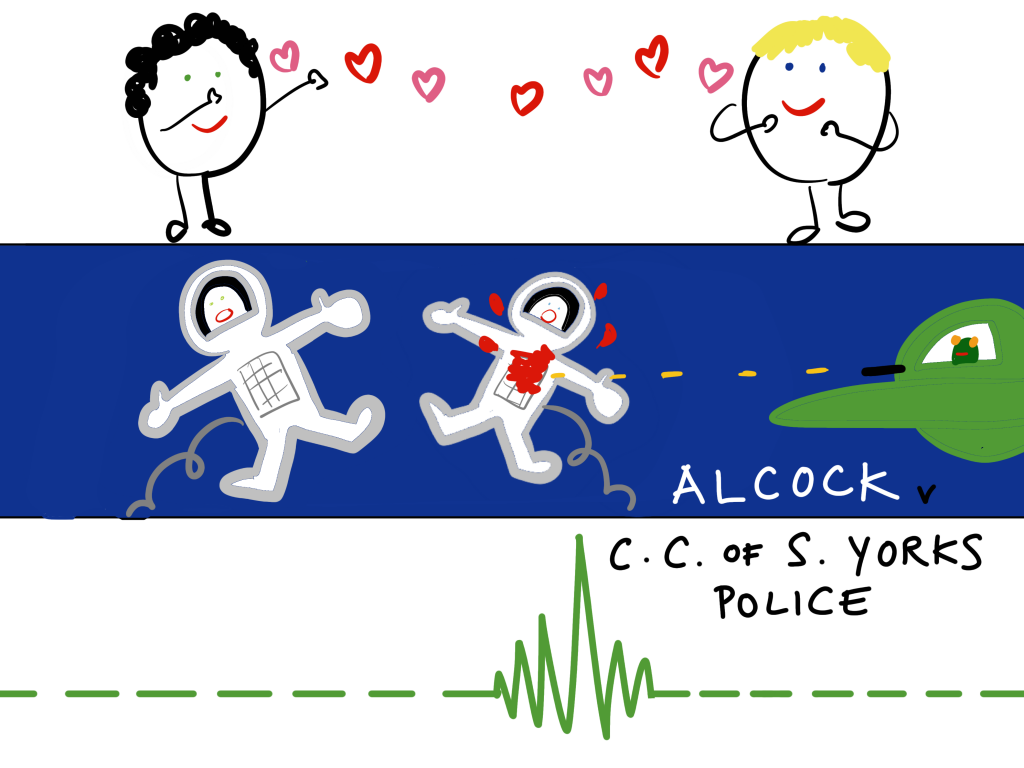

This case was viewed at the time as pushing the boundaries of who should be able to claim as a secondary victim. As you will see below the court in the subsequent case of Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police (1992) (HoL) worked to put in place restrictions on any expansion to who could claim as a secondary victim.

DUTY OF CARE

It is much more difficult to establish a duty of care for a secondary victim. The test follows the Caparo v Dickman structure but is more restrictive. As you will see proving a relationship of sufficient proximity is especially challenging.

FORESEEABILITY OF HARM

Unlike for primary victims psychiatric harm must be a foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s negligence (Bourhill v Young (1943) (HoL)).

A woman getting off a tram heard a motorbike accident (caused by the defendant’s speeding) which occurred about 50 feet away from her. She later said she didn’t know, from the sound, if she was ‘going to get it or not’. Later on she saw the victim’s blood on the pavement. Her child was stillborn shortly after and she claimed this was due to nervous shock suffered as a result of her experiences. The court held that she could not recover because the defendant did not owe her a duty of care. The nervous shock suffered by someone standing behind a tram, unseen by the defendant, who then later saw the scene of the accident was not a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s negligence.

Whether psychiatric damage was reasonably foreseeable will be based on how the victim of ‘reasonable fortitude’ (Brice v Brown (1984) (HC)) or with ‘customary phlegm’ (Bourhill v Young (1943) (HoL)) would be expected to respond. Therefore the fact that she was more vulnerable because of her pregnancy could not be taken into account.

THIN SKULL/EGGSHELL RULE

The Thin Skull or Eggshell Rule as set out in Smith v Leech Brain (1962) (HC) (see Remoteness Section) concerning what level of harm is foreseeable applies to cases of nervous shock as well as physical damage. If nervous shock would have been reasonably foreseeable in a victim of ‘reasonable fortitude’ then the defendant will be liable for the full extent of the psychiatric damage caused even if that particular victim suffered to a greater extent because they had a ‘thin skull’. In other words, the defendant must take the claimant as they find them. This was set out in Brice v Brown (1984) (HC).

Brice had suffered from hysterical personality disorder her whole life but her condition was much worsened when she and her daughter were involved in a car accident. The defendant argued that he could not be liable for Brice’s condition as it was not foreseeable. However, the court ruled that as long as some form of nervous shock was foreseeable in someone of ‘reasonable fortitude’ then the defendant would be liable for the whole extent of the damage even if this included an existing condition. A car accident could have led to nervous shock even in a victim of ‘customary phlegm’.

MEDICALLY RECOGNISED ILLNESS

As for a primary victim the claimant must prove that their psychiatric harm is a medically recognised form of psychiatric illness. Courts will refer to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association and the Glossary of Mental Disorders in the International Classification of Diseases.

In Hinz v Berry (1970) (CoA) the Hinz family (parents and 8 children) had been having a picnic when Mr Berry’s car tyre burst and he swerved into their parked car. Mr Hinz was killed and the rest of the family injured apart from Mrs Hinz and one child who witnessed the accident from the other side of the road. Mrs Hinz could recover for nervous shock but not for any additional grief or worry because this was not a recognised psychiatric illness.

However, in Vernon v Bosley (1997) (CoA) a claimant who was diagnosed with ‘pathological grief’ was able to recover.

PROXIMITY

The case of Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police (1992) (HoL) put in place certain control mechanisms for determining whether the claimant and defendant had a relationship of sufficient proximity. Claimants would be assessed on;

- Relational proximity – their relationship with the victim.

- Spatial and temporal proximity – proximity in time and space to the event.

- Direct perception of events – the means by which the shock was caused.

Alcock was a test case concerning relatives and friends of the victims of the Hillsborough disaster in 1989 in which 96 Liverpool football fans died and 450 were injured in a huge crush of supporters trying to enter the stadium. Some of the claimants had been at the stadium and witnessed the event whilst others had seen the event on television, heard about it on the radio or been told by someone else. The House of Lords held that for various reasons there was insufficient proximity between them and the victims upon which to found a claim in negligence.

Alcock was only the third case to be heard by the House of Lords regarding a claim from a secondary victim. The first had been Bourhill v Young (1943) (HoL), then McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983) (HoL) which had extended who could potentially claim as a secondary victim, and thirdly Alcock which was used to put in places restrictions to who could claim.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CLAIMANT AND VICTIM

There must be a close relationship between the claimant and the victim, this will depend on the facts of the case. The closer the relationship is the more likely there is to be a duty of care. In Alcock the judges were divided on whether only specific relationships should qualify (e.g. parent/child or spouse/partner) or whether it should be based on ‘close ties of love and affection’. In general it seems that relationships such as parent/child and spouse/fiancé will automatically succeed but not grandparent, sibling or aunt/uncle.

However, it will depend on whether a close enough relationship can be proved or disproved. One of the Alcock claimants had been in the stadium at the time and knew that his brother was in the area where the human crush happened. He was not able to claim because no evidence had been submitted to prove that his relationship with his brother was one of sufficient love and affection.

VICTIM = DEFENDANT

In Greatorex v Greatorex (2000) (CoA) it was held that a secondary victim will not be able to claim if the victim they fear for is also the defendant. A fireman suffered nervous shock after seeing his son in the aftermath of a car accident, however the accident had been caused by the son’s negligent driving so he was not able to claim.

PROXIMITY IN TIME AND SPACE

There must be proximity in time and space between the claimant and the harm suffered by the victim. This will generally be witnessing the accident or its immediate aftermath.

In McLoughlin v O’Brian (1983) (HoL) the mother saw her family in the hospital two hours after the accident. They had not yet been seen to by medical staff; they were still covered in blood and dirt from the accident and visibly shaken and upset. This was considered sufficiently proximate in time and space, the secondary victim had arrived within the immediate aftermath and seen loved ones in substantially the same condition as when they met with the accident..

In Alcock most of the claimants did not see the victims until nine hours later when the bodies were in a mortuary. The blood on one victim was described as ‘too dry’ to have caused nervous shock in their relative. Some commentators saw this as a harsh restriction but the court was keen not to extend liability beyond McLoughlin and stuck to a strict interpretation of what constitutes the immediate aftermath of an event.

In Taylor v A Novo (2013) a daughter claimed for psychiatric damage caused by the death of her mother who had died as a consequence of an accident at work. The daughter had not been present at the accident or the immediate aftermath so was unable to recover.

EXCEPTIONS

Exceptions to these strict rules can be made in certain circumstances. In W v Essex County Council (2000) (HoL) the court acknowledged that in some situations having to witness the event or immediate aftermath is too restrictive. In this case parents of children who had been abused by their foster son sued the council for the psychiatric harm caused by the knowledge that this abuse had taken place. Even though the parents had only found out about the abuse four weeks after it happened they were not barred from taking their claim forward for lack of proximity.

Note this was a striking out claim so the court was only being asked whether the claim could continue not for an ultimate decision on whether a duty of care existed.

HOW WAS THE SHOCK CAUSED?

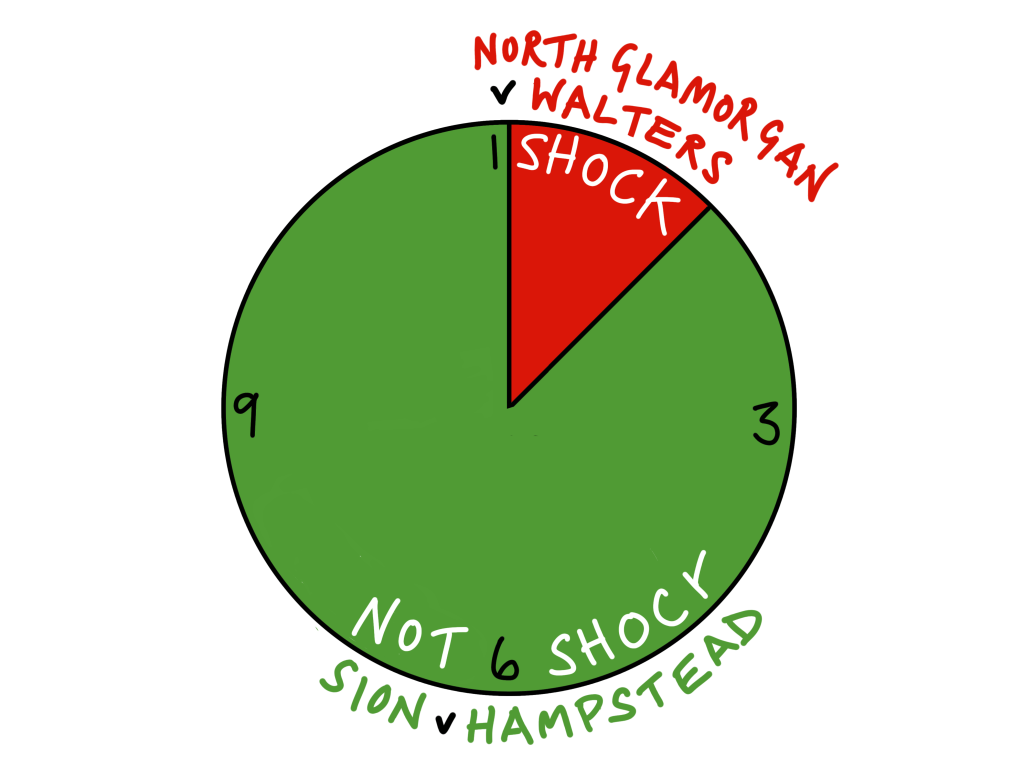

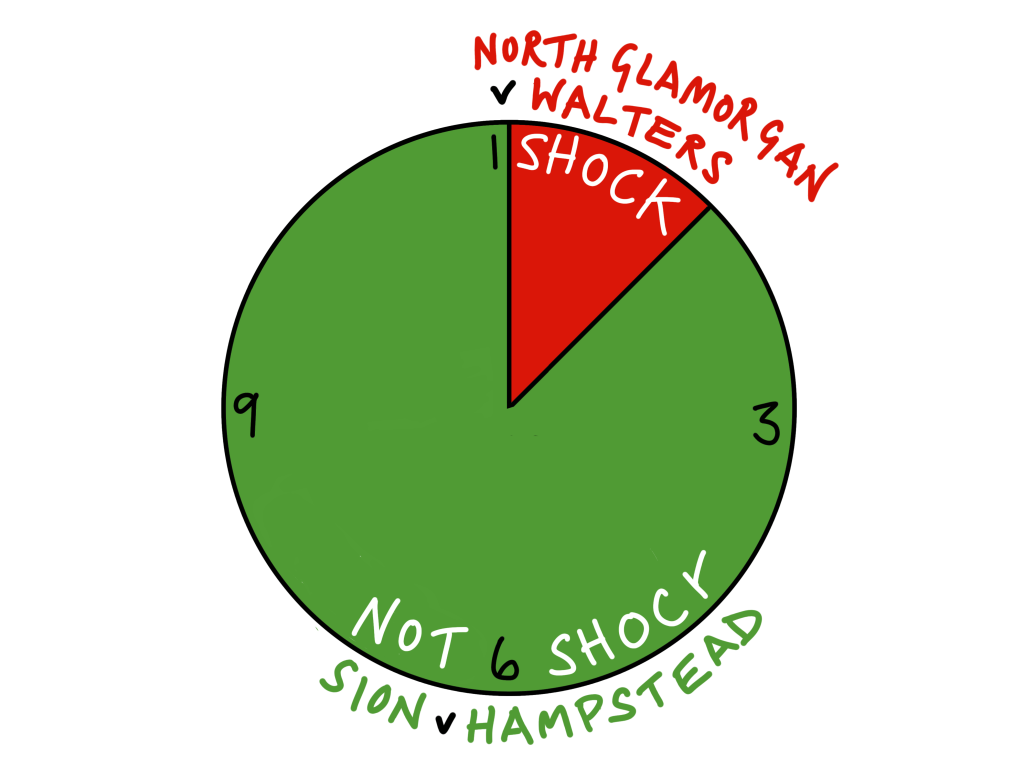

The damage must be a result of the sudden shock of witnessing, with their own unaided senses, a horrific event or its aftermath and not a reaction to a more sustained period of events. Compare these two cases…

| In North Glamorgan NHS Trust v Walters (2002) (CoA) a mother suffered nervous shock over a period of 36 hours as she was informed of the deterioration in health of her 10 month old baby who then died as a result of medical negligence. She was able to recover as the time span could be considered as one event and each element of bad news had caused an evident psychiatric reaction. |

In Sion v Hampstead HA (1994) (CoA) the claimant’s child was in intensive care for fourteen days and the damage had occurred in a much more prolonged way as the claimant became aware of the hospital’s medical negligence. ‘A psychiatric illness caused not by a sudden shock but by an accumulation of more gradual assaults on the nervous system over a period of time is not enough’ Peter Gibson LF. |

In the more recent case of Liverpool Women’s Hospital v Ronayne (2015) (CoA) a husband witnessed his wife in hospital after a botched operation. She was hooked up to drips and monitors and very bloated ‘like the Michelin man’. The court rejected his claim for PTSD, the effect on him had been cumulative caused by a number of events not one sudden shock. He had been forewarned of her condition by the doctors and the sight of his wife was not horrifying enough to qualify as an event that could cause nervous shock.

SECOND-HAND NEWS

In Alcock the claimants who had watched the accident on television were unable to claim. The court held that as broadcasters had to abide by rules on not showing the suffering or death of individuals it would have been impossible for those watching at home to identify their loved ones. It was discussed that if a live broadcast showed an event in which everyone died this may count as witnessing the event.

The claimants who had been at the stadium were unable to claim for other reasons. One, who had lost his brother, could not claim because there was insufficient evidence to establish that he had had a relationship of sufficient love and affection with his brother. Another was the brother-in-law of a victim, this was deemed a relationship of insufficient proximity.

In W v Essex County Council (2000) (HoL) the parents only found out about the abuse through another person, i.e. not with their own unaided senses. This was not sufficient to have the claim struck out, although being a striking out claim rather than a full trial it was not decided whether the parents would be successful on this point.

FAIR, JUST & REASONABLE

Policy considerations will also come into play when assessing whether a secondary victim should recover.

NERVOUS SHOCK SUFFERED BY RESCUERS

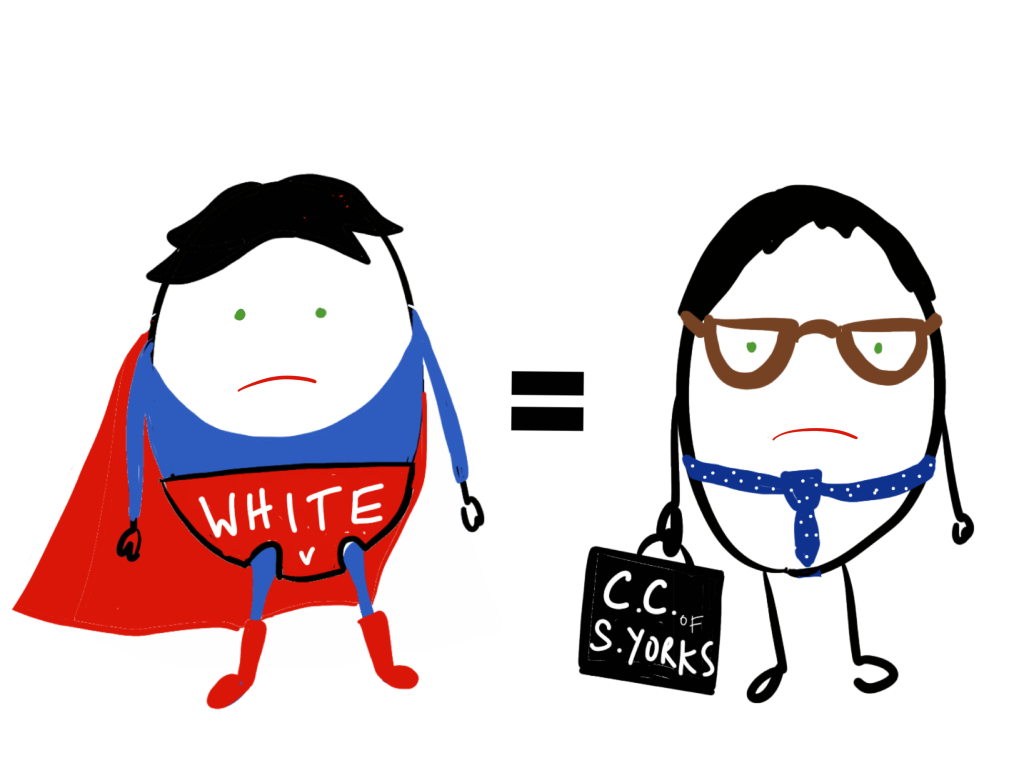

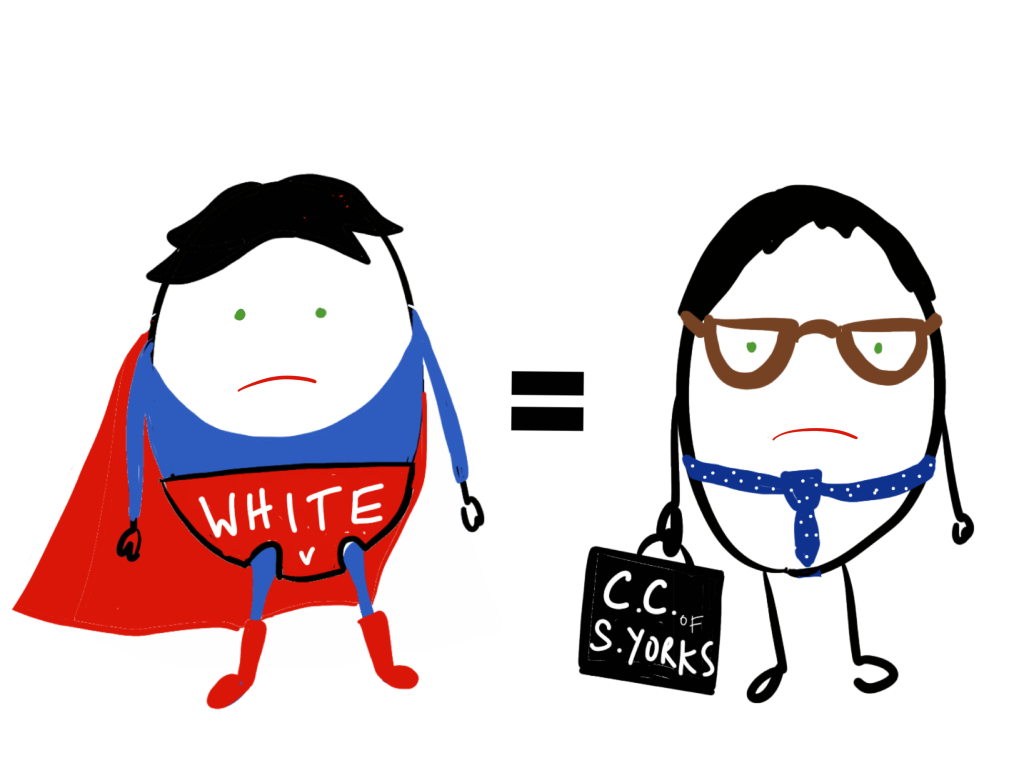

The law regarding whether rescuers can claim for psychiatric damage has become more restrictive since White v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1998) (HoL).

PRE-WHITE

Chadwick v British Railway Board (1967) (HC) demonstrates the courts’ more lenient position pre-White. Chadwick suffered depression and anxiety after spending hours trying to free people from a huge train wreckage in which 90 people were killed. He was treated as a primary victim even though he was not involved in the accident itself but because his involvement in the aftermath was deemed dangerous enough to make him fear for his personal safety.

POST-WHITE

Now rescuers are offered no special status by the law. They have to claim as primary or secondary victims like any other claimant. A rescuer or bystander who suffers nervous shock due to witnessing a horrific event can claim as a primary victim only if they were in fear for their own personal safety. The case of White v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire (1998) (HoL) concerned the police officers who were on duty during the Hillsborough disaster and who had to deal with the aftermath. They were given no special treatment as rescuers (even though Lord Oliver in Alcock had highlighted the special status of rescuers) and nor were they able to claim as primary or secondary victims. The police officers had not been in fear for their own safety at any time and they did not fulfil the Alcock criteria for secondary victims either.

The case was undoubtedly decided on public policy grounds. The families of victims in Alcock had not recovered so it was deemed somewhat inappropriate to allow the police offers to recover, particularly as the police force had admitted that their negligence had caused the accident. There had also been no claims from other emergency services such as paramedics or doctors. The court was also concerned about the expansion of claims for psychiatric damage. They decided to stem the flow by not allowing the claimants in White to recover damages,

A case that followed White was Cullin v London Fire & Civil Defence Authority (1999) (CoA) in which a fireman claimed damages for nervous shock after seeing two colleagues trapped in a burning building and attempting a failed rescue. He was classified as a primary victim because of the physical danger involved in the rescue attempt.

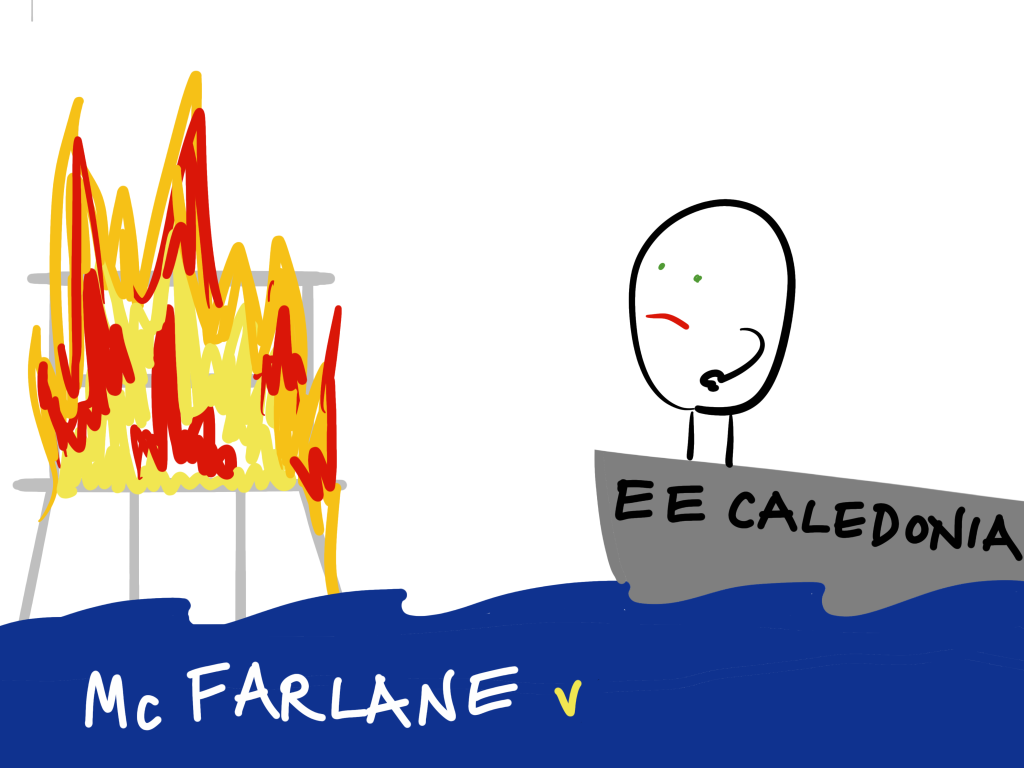

NERVOUS SHOCK SUFFERED BY BYSTANDERS

The question of whether in any circumstances a duty of care would extend to bystanders, an exception made to the requirement for proximity of relationship was discussed by Lord Oliver in Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police (1992) (HoL). He gave the theoretical example of ‘that of a petrol tanker careering out of control into a school in session and bursting into flames. I would not be prepared to rule out a potential claim by a passer-by so shocked by the scene as to suffer psychiatric illness’. This exception was argued in the case of McFarlane v EE Caledonia (1994) (HC).

The court set out that bystanders can recover if:

- They were in the vicinity of the accident and only avoided physical harm through good luck, or

- Although not in danger the bystander was close enough that they could have believed themselves to be in danger, or

- Although not in the vicinity at the time they were within the area of danger later on as a rescuer.

McFarlane, who worked on a North Sea oil rig, happened to be on a nearby boat when a devastating fire broke out on the rig. The boat he was on helped survivors from the water. However, McFarlane was not able to recover because he did not fall under any of the categories as he had never been sufficiently near the danger. Although the boat he was on had for a few minutes been only 50 metres away from the fire no one on board had ever been in danger. He was also not classed as a rescuer as although his boat had rescued people it had never been close enough to the oil rig to be in danger. Despite seeing colleagues on the oil rig on fire and jumping into the sea he did not satisfy the secondary victim criteria either. This case shows how difficult it would be to recover as a bystander.

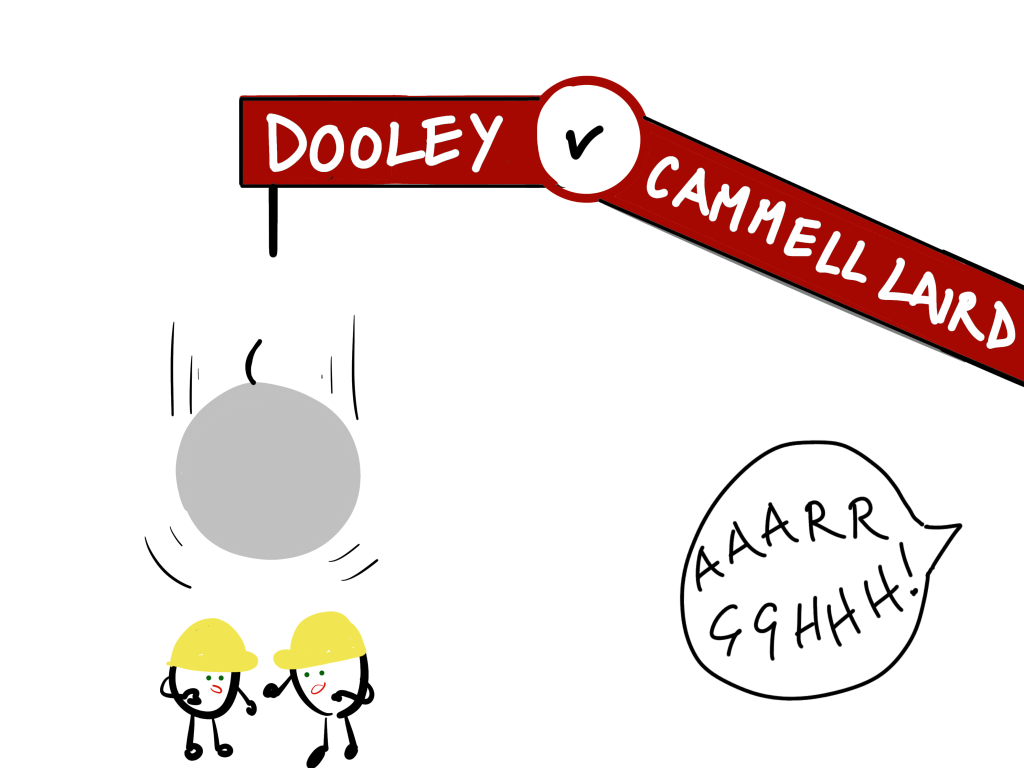

NERVOUS SHOCK SUFFERED BY UNWITTING PARTICIPANTS

Another category of potential claimant is the unwitting participant, someone who suffers nervous shock because they believe that their actions have accidentally led to another’s death (Dooley v Cammell Laird (1951) (Assizes)).

Dooley was operating a crane when a cable snapped and the load fell. Dooley knew that his colleagues were working underneath where the load had fallen. He suffered nervous shock believing that he had killed them. Although they were in fact uninjured Dooley could claim as a secondary victim.

In the post-White case of Monk v PC Harrington (2008) (HC) a similar set of events happened but in this case Monk heard about the accident over the radio before going to help rescue the workers. He was unable to recover as a rescuer as he could not show sufficient fear for his own safety. He was also unable to recover as an unwitting participant as he was unable to show a reasonable basis for his belief that, as the person responsible for the installation of the platform that had collapsed, he was responsible for the accident.